Upland and Agriculture Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naming of Traditional Rice Varieties by the Farmers of Laos S

CHAPTER 10 Naming of traditional rice varieties by the farmers of Laos S. Appa Rao, J.M. Schiller, C. Bounphanousay, A.P. Alcantara, and M.T. Jackson The collection of traditional rice varieties from throughout Laos, together with a sum- mary of the diversity observed and its conservation, has been reviewed in Chapter 9 of this monograph. While undertaking the collection of germplasm samples from 1995 to early 2000, information was collected from farmers on the special traits and significance of the different varieties, including the vernacular names and their mean- ings. Imperfect as literal translations might be, the names provide an insight into the diversity of the traditional rice varieties of Laos. Furthermore, the diversity of names can, when used with care, act as a proxy for genetic diversity. When collecting started, variety names were recorded in the Lao language and an agreed transliteration into English was developed. The meanings of the variety names were obtained from all possible sources, but particularly from the farmers who donated the samples, together with Lao extension officers and Lao research staff members who understood both Lao and English. Variety names were translated literally, based on the explanations provided by farmers. For example, the red color of glumes is often described in terms of the liquid from chewed betel leaf, which is dark red. Aroma is sometimes indicated by the names of aromatic flowers like jasmine or the response to the aroma that is emitted by the grain of particular varieties during cooking. This chapter provides a summary of the information collected on the naming of traditional Lao rice varieties. -

Northern Economic Corridor in the Lao People's

SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT NORTHERN ECONOMIC CORRIDOR IN THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC August 2002 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 18 July 2002) Currency Unit – Kip (KN) KN1.00 = $0.0000993 $1.00 = KN10,070 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected person DOR – Department of Roads EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMP – Environment Management Plan HIV/AIDS – human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome Lao PDR – Lao People’s Democratic Republic MAF – Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry MCTPC – Ministry of Communication, Transport, Post, and Construction NBCA – national biodiversity conservation area NPA – national protected area PRC – People’s Republic of China SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment STEA – Science, Technology and Environment Agency NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. CONTENTS Page MAP ii I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT 2 A. Houayxay to Ban Nam Ngeun 2 B. Ban Nam Ngeun to the Louang Namtha Bypass 3 C. Southern End of Louang Namtha Bypass to Boten 3 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT 4 A. Physical Resources 4 B. Ecological Resources 4 C. Human and Economic Development 5 D. Quality of Life Values 6 IV. ALTERNATIVES 7 V. ANTICIPATED ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS AND MITIGATION MEASURES 8 A. Soil Erosion 8 B. Loss of Vegetation and Habitat 9 C. Impacts on Wildlife 9 D. Impacts on Wildlife Through Increased Pressure from Illegal Trade 9 E. Overexploitation of Forest Resources Through Unsustainable Logging 9 F. Dust and Air Pollution 10 G. Noise 10 H. Loss of Agricultural Land 10 I. Encroachment on Irrigation Structures 11 J. -

Evaluation of the EC Cooperation with the LAO

Evaluation of EC co-operation with the LAO PDR Final Report Volume 2 June 2009 Evaluation for the European Commission This evaluation was commissioned by: Italy the Evaluation Unit common to: Aide à la Décision Economique Belgium EuropeAid Co-operation Office, Directorate-General for Development and PARTICIP GmbH Germany Directorate-General for External Relations Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik Germany Overseas Development Institute United Kingdom European Institute for Asian Studies Belgium Istituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales Spain The external evaluation team was composed of Landis MacKellar (team leader), Jörn Dosch, Maija Sala Tsegai, Florence Burban, Claudio Schuftan, Nilinda Sourinphoumy, René Madrid, Christopher Veit, Marcel Goeke, Tino Smaïl. Particip GmbH was the evaluation contract manager. The evaluation was managed by the evaluation unit who also chaired the reference group composed by members of EC services (EuropeAid, DG Dev, DG Relex, DG Trade), the EC Delegations in Vientiane and Bangkok and a Representative of the Embassy of the LAO PDR. Full reports of the evaluation can be obtained from the evaluation unit website: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/evaluation/evaluation_reports/index_en.htm The opinions expressed in this document represent the authors’ points of view, which are not necessarily shared by the European Commission or by the authorities of the countries concerned. Evaluation of European Commission’s Cooperation with ASEAN Country Level Evaluation Final Report The report consists of 2 volumes: Volume I: FINAL REPORT Volume II: Annexes VOLUME I: DRAFT FINAL REPORT 1. Introduction 2. Development Co-operation Context 3. EC strategy and the logic of EC support 4. Findings 5. Conclusions 6. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Report No.: 62073 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC PROVINCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT (CREDIT 3131) June 10, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized IEG Public Sector Evaluation Independent Evaluation Group Public Disclosure Authorized Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = Laotian Kip 1998 US$1.00 Kip 3,298 1999 US$1.00 Kip 7,102 2000 US$1.00 Kip 7,888 2001 US$1.00 Kip 8,955 2002 US$1.00 Kip 10,056 2003 US$1.00 Kip 10,569 2004 US$1.00 Kip 10,585 2005 US$1.00 Kip 10,655 2006 US$1.00 Kip 10,160 2007 US$1.00 Kip 9,603 2008 US$1.00 Kip 8,744 2009 US$1.00 Kip 8,393 Abbreviations and Acronyms ASEAN Association of South-East Asian Nations CAS Country Assistance Strategy DCA Development Credit Agreement ERR Economic Rate of Return GOL Government of the Lao PDR ICR Implementation Completion Report IEG Independent Evaluation Group Lao PDR Lao People’s Democratic Republic M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MPH Ministry of Public Health MPWT Ministry of Public Works and Transport NAMPAPA (MPWT) Water Supply Enterprise (for urban areas) NAMSAAT (MPH) Institute of Clean Water (for rural areas) NEM New Economic Mechanism PAD Project Appraisal Document PPAR Project Performance Assessment Report Fiscal Year Government: October 1 – September 30 Director-General, Independent Evaluation : Mr. Vinod Thomas Director, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi (acting) Manager, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi Task Manager : Mr. -

Ethnic Minority

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Lao People’s Democratic Republic Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues LAO PEOPLE'S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC Last update: November 2012 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous People‘s Issues - Lao People's Democratic Republic .............................................................................................. 1 Summary ............................................................................................................. 1 1. Main characteristics of indigenous peoples ............................................................. 2 1.1 Demographic status ...................................................................................... 4 2. Sociocultural status ........................................................................................... -

Executive Summary, Oudomxay Province

Executive Summary, Oudomxay Province Oudomxay Province is in the heart of northern Laos. It borders China to the north, Phongsaly Province to the northeast, Luang Prabang Province to the east and southeast, Xayabouly Province to the south and southwest, Bokeo Province to the west, and Luang Namtha Province to the northwest. Covering an area of 15,370 km2 (5,930 sq. ml), the province’s topography is mountainous, between 300 and 1,800 metres (980-5,910 ft.) above sea level. Annual rain fall ranges from 1,900 to 2,600 millimetres (75-102 in.). The average winter temperature is 18 C, while during summer months the temperature can climb above 30 C. Muang Xai is the capital of Oudomxay. It is connected to Luang Prabang by Route 1. Oudomxay Airport is about 10-minute on foot from Muang Xai center. Lao Airlines flies from this airport to Vientiane Capital three times a week. Oudomxay is rich in natural resources. Approximately 60 rivers flow through its territory, offering great potential for hydropower development. About 12% of Oudomxay’s forests are primary forests, while 48% are secondary forests. Deposits of salt, bronze, zinc, antimony, coal, kaolin, and iron have been found in the province. In 2011, Oudomxay’s total population was 307,065 people, nearly half of it was females. There are 14 different ethnic groups living in the province. Due to its mountainous terrains, the majority of Oudomxay residents practice slash- and-burn agriculture, growing mountain rice. Other main crops include cassava, corn, cotton, fruits, peanut, soybean, sugarcane, vegetables, tea, and tobacco. -

Ethnic Group Development Plan LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure

Ethnic Group Development Plan Project Number: 42203 May 2016 LAO: Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project - Additional Financing Prepared by Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry for the Asian Development Bank. This ethnic group development plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Ethnic Group Development Plan Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject Tai Lue Village, Lao PDR TABLE OF CONTENTS Topics Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND TERMS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A10-1 A. Introduction A10-1 B. The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-1 C. Ethnic Groups in the Subproject Areas A10-2 D. Socio-Economic Status A10-2 a. Land Issues A10-3 b. Language Issues A10-3 c. Gender Issues A10-3 d. Social Health Issues A10-4 E. Potential Benefits and Negative Impacts of the Subproject A10-4 F. Consultation and Disclosure A10-5 G. Monitoring A10-5 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION A10-6 1.1 Objectives of the Ethnic Groups Development Plan A10-6 1.2 The Northern Rural Infrastructure Development Sector Project A10-6 (NRIDSP) 1.3 The Nam Beng Irrigation Subproject A10-6 2. -

Study of the Provincial Context in Oudomxay 1

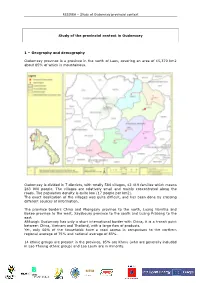

RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context Study of the provincial context in Oudomxay 1 – Geography and demography Oudomxay province is a province in the north of Laos, covering an area of 15,370 km2 about 85% of which is mountainous. Oudomxay is divided in 7 districts, with totally 584 villages, 42 419 families which means 263 000 people. The villages are relatively small and mainly concentrated along the roads. The population density is quite low (17 people per km2). The exact localization of the villages was quite difficult, and has been done by crossing different sources of information. The province borders China and Phongsaly province to the north, Luang Namtha and Bokeo province to the west, Xayaboury province to the south and Luang Prabang to the east. Although Oudomxay has only a short international border with China, it is a transit point between China, Vietnam and Thailand, with a large flow of products. Yet, only 66% of the households have a road access in comparison to the northern regional average of 75% and national average of 83%. 14 ethnic groups are present in the province, 85% are Khmu (who are generally included in Lao Theung ethnic group) and Lao Loum are in minority. MEM Lao PDR RESIREA – Study of Oudomxay provincial context 2- Agriculture and local development The main agricultural crop practiced in Oudomxay provinces is corn, especially located in Houn district. Oudomxay is the second province in terms of corn production: 84 900 tons in 2006, for an area of 20 935 ha. These figures have increased a lot within the last few years. -

Market Chain Assessments

Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project (RRP LAO 50236) Market Chain Assessments February 2019 Lao People’s Democratic Republic Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project Sustainable Rural Infrastructure and Watershed Management Sector Project (RRP LAO 50236) CONTENTS Page I. HOUAPHAN VEGETABLE MARKET CONNECTION 1 A. Introduction 1 B. Ban Poua Irrigation Scheme 1 C. Markets 1 D. Market Connections 4 E. Cross cutting issues 8 F. Conclusion 9 G. Opportunity and Gaps 10 II. XIANGKHOUANG CROP MARKETS 10 A. Introduction 10 B. Markets 11 C. Conclusion 17 D. Gaps and Opportunities 17 III. LOUANGPHABANG CROP MARKET 18 A. Introduction 18 B. Markets 18 C. Market connections 20 D. Cross Cutting Issues 22 E. Conclusion 23 F. Opportunities and Gaps 23 IV. XAIGNABOULI CROP MARKETS 24 A. Introduction 24 B. Market 24 C. Market Connection 25 D. Conclusion 28 E. Opportunities and Gaps 28 V. XIANGKHOUANG (PHOUSAN) TEA MARKET 29 A. Introduction 29 B. Xiangkhouang Tea 30 C. Tea Production in Laos 30 D. Tea Markets 31 E. Xiangkhouang Tea Market connection 33 F. Institutional Issues 38 G. Cross Cutting Issues 41 H. Conclusion 41 I. Opportunities and Gaps 42 VI. XIANGKHOUANG CATTLE MARKET CONNECTION ANALYSIS 43 A. Introduction 43 B. Markets 43 C. Export markets 44 D. Market Connections 46 E. Traders 49 F. Vietnamese Traders 49 G. Slaughterhouses and Butchers 50 H. Value Creation 50 I. Business Relationships 50 J. Logistics and Infrastructure 50 K. Quality – Assurance and Maintenance 50 L. Institutions 50 M. Resources 51 N. Cross Cutting Issues 51 O. Conclusion 51 P. -

2020 Quarter 2 Report (Pdf) Download

Assistance Report 2nd Quarter 2020 Quarter Funding Total $ 14,231.98 To Date Funding Total $711,772.97 Area of Operation 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter 4th Quarter To Date Thailand $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 $0.00 Laos $570.00 $13,981.00 $0.00 $0.00 $14,551.00 Student Aid - Thailand $2,186.20 $250.98 $0.00 $0.00 $2,437.18 Quarter Total $2,756.20 $14,231.98 $0.00 $0.00 $16,988.18 Total to Date $697,540.99 $711,772.97 $0.00 $0.00 $711,772.97 Motions and Actions 2nd Quarter 2020 20-06 Approved, Thailand Student Assistance – April 20-07 Approved, Laos Quality of Life - Smith 20-08 Approved, Laos Quality of Life - Smith 20-09 Approved, Thailand Student Assistance – May 20-10 Approved, Laos Quality of Life - Smith 20-11 Approved, Laos Quality of Life - Smith Respectfully submitted, Les Thompson Chairman TLCB Assistance Committee 15 July 2020 Motion details attached below: Motion 20-06 Student Assistance Program - April Estimated Amount = $675.00 Actual Amount = $250.98 For Satawat Sri-in, I make the following motion: Move that 22,000 baht be approved for our continuing student assistance for April 2020. College/University Students @ 2,000thb/month 1) Juthathip Siriwong 4th Year English Teaching 2) Wipada Phetsuwan 4th Year Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat U (Sakon Nakhon) 3) Nutchanat Niwongsa 4th Year NPU 4) Nantawee Chanapoch 4th Year NPU 5) Natsupha Pholman 4th Year Burapha University - Chonburi 6) Darart Promarrak 3rd Year MCU 7) Thamonwan Thungnathad 3rd Year NPU 8) Nittaya Manasen 3rd Year NPU 9) Matchima Khanda 2nd Year Sakon Nakhon Rajabhat U (Mathmatics Teaching) 10) Achiraya Thiauthit 1st Year NPU 11) Sawini Manaonok 1st Year UBU Total: 22,000thb Exchange Rate on 23 March 2020 is 32.8THB per 1USD Motion 20-07 Laos Quality of Life Program Ban Houai Awm Primary School, Phou Kout District, Xiangkhouang, Laos Estimated Amount = $3,451 Actual Amount = $3,298.00 2020 Budget Current $15,430 - $3,451= -$11,979 remaining. -

Municipal Solid Waste Management 4-1 4.1 the Capital of Vientiane

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment Data Collection Survey on Waste Management Sector in The Lao People’s Democratic Republic Final Report February 2021 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EX Research Institute Ltd. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. GE KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. JR 21-004 Locations of Survey Target Areas 1. Meeting at Transfer Station 2. Vang Vieng Landfill Site 3. Savannakhet UDAA 4. Online meeting with MONRE’s Vice Minister 5. Outlook of Health-care Waste Incinerator, 6. Final disposal site in Xayaboury District Luang Prabang District 7. Factory visit to EPOCH Co., Ltd. 8. DFR Joint-Workshop (online) Survey Photos Executive Summary 1. Background and objective In the Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos), the remaining capacity of the final disposal site in cities is becoming insufficient due to the influence of the population increase and the progress of urbanization in recent years. The waste collection rate remains at a low level. In many cases, medical waste and hazardous waste are also dumped in municipal waste disposal sites and vacant lots without proper treatment. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE) is in charge of formulating policies and plans for overall environmental measures, including waste management, and coordinating related ministries and agencies. On the other hand, the actual waste management work is under the jurisdiction of different ministries and agencies depending on the type of waste. In the central government, the Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) oversees general waste, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (MOIC) is in charge of industrial waste, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) is in charge of medical waste. -

Widening the Geographical Reach of the Plain of Jars, Laos

Widening the Geographical Reach of the Plain of Jars, Laos Lia Genovese Abstract This research report summarises ongoing fieldwork at the Plain of Jars in Laos and details megalithic artefacts in newly-discovered sites populated with jars fashioned from a variety of rocks. With two exceptions, the jars at these remote sites are in single digits and are not accompanied by plain or decorated stone discs, used as burial markers or for commemorative purposes. The sites’ isolated location bears implications for the geographical reach of the Plain of Jars by widening our understanding of this megalithic tradition in Mainland Southeast Asia. Introduction The Plain of Jars is spread over the provinces of Xieng Khouang and Luang Prabang (Map 1). All the sites are located at latitude 19°N, while the longitude starts at 102°E for sites in Luang Prabang and progresses to 103°E for locations in Xieng Khouang. As the leader of the first large-scale survey in 1931- 1933, the French archaeologist Madeleine Colani (1866-1943) documented 26 sites (Genovese 2015a: 58-59). Sites can include a group of jars, a quarry, a stone outcrop like a rock formation protruding through the soil level, or a manufacturing site, and can hold from one single jar to several hundred units.1 Dozens of new sites have since been discovered, Map 1. Contoured in red: Xieng Khouang province. The contour taking the total to just over in dark green delineates Phou Khoun district in Luang Prabang 100, with the quantity of province (adapted from d-maps). documented stone artefacts now exceeding 2,100 jars and The Journal of Lao Studies, Volume 7, Issue 1, pps 55-74.