Hierarchical Control Versus Autoregulation of Carbohydrate Utilization in Bacteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Camp Receptor Protein–Camp Plays a Crucial Role in Glucose–Lactose Diauxie by Activating the Major Glucose Transporter Gene in Escherichia Coli

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 94, pp. 12914–12919, November 1997 Biochemistry cAMP receptor protein–cAMP plays a crucial role in glucose–lactose diauxie by activating the major glucose transporter gene in Escherichia coli KEIKO KIMATA*, HIDEYUKI TAKAHASHI*, TOSHIFUMI INADA*, PIETER POSTMA†, AND HIROJI AIBA*‡ *Department of Molecular Biology, School of Science, Nagoya University, Chikusa, Nagoya 464-01, Japan; and †E. C. Slater Institute, BioCentrum, University of Amsterdam, Plantage Muidergracht 12, 1018 TV Amsterdam, The Netherlands Communicated by Sydney Kustu, University of California, Berkeley, CA, September 17, 1997 (received for review May 2, 1997) ABSTRACT The inhibition of b-galactosidase expression certain conditions, for example, when added to cells growing in a medium containing both glucose and lactose is a typical on a poor carbon source such as glycerol or succinate (6, 7). example of the glucose effect in Escherichia coli. We studied the Glucose is thought to reduce cAMP level by decreasing the glucose effect in the lacL8UV5 promoter mutant, which is phosphorylated form of enzyme IIAGlc, which is proposed to independent of cAMP and cAMP receptor protein (CRP). A be involved in the activation of adenylate cyclase (3–5). strong inhibition of b-galactosidase expression by glucose and Glucose also is known to reduce the CRP level through the a diauxic growth were observed when the lacL8UV5 cells were autoregulation of the crp gene (7–10). grown on a glucose–lactose medium. The addition of isopropyl When E. coli finds both glucose and lactose in the medium, b-D-thiogalactoside to the culture medium eliminated the it preferentially uses the glucose, and the use of lactose is glucose effect. -

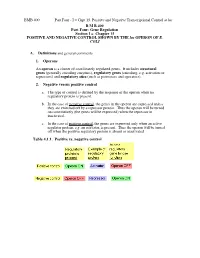

I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at Lac BMB

BMB 400 Part Four - I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at lac B M B 400 Part Four: Gene Regulation Section I = Chapter 15 POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE CONTROL SHOWN BY THE lac OPERON OF E. COLI A. Definitions and general comments 1. Operons An operon is a cluster of coordinately regulated genes. It includes structural genes (generally encoding enzymes), regulatory genes (encoding, e.g. activators or repressors) and regulatory sites (such as promoters and operators). 2. Negative versus positive control a. The type of control is defined by the response of the operon when no regulatory protein is present. b. In the case of negative control, the genes in the operon are expressed unless they are switched off by a repressor protein. Thus the operon will be turned on constitutively (the genes will be expressed) when the repressor in inactivated. c. In the case of positive control, the genes are expressed only when an active regulator protein, e.g. an activator, is present. Thus the operon will be turned off when the positive regulatory protein is absent or inactivated. Table 4.1.1. Positive vs. negative control BMB 400 Part Four - I = Chpt 15. Positive and Negative Transcriptional Control at lac 3. Catabolic versus biosynthetic operons a. Catabolic pathways catalyze the breakdown of nutrients (the substrate for the pathway) to generate energy, or more precisely ATP, the energy currency of the cell. In the absence of the substrate, there is no reason for the catabolic enzymes to be present, and the operon encoding them is repressed. In the presence of the substrate, when the enzymes are needed, the operon is induced or de-repressed. -

(CRP) on Porin Genes and Its Own Gene in Yersinia Pestis

Gao et al. BMC Microbiology 2011, 11:40 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2180/11/40 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Regulatory effects of cAMP receptor protein (CRP) on porin genes and its own gene in Yersinia pestis He Gao1†, Yiquan Zhang1†, Lin Yang1,2, Xia Liu1,2, Zhaobiao Guo1, Yafang Tan1, Yanping Han1, Xinxiang Huang2, Dongsheng Zhou1*, Ruifu Yang1* Abstract Background: The cAMP receptor protein (CRP) is a global bacterial regulator that controls many target genes. The CRP-cAMP complex regulates the ompR-envZ operon in E. coli directly, involving both positive and negative regulations of multiple target promoters; further, it controls the production of porins indirectly through its direct action on ompR-envZ. Auto-regulation of CRP has also been established in E. coli. However, the regulation of porin genes and its own gene by CRP remains unclear in Y. pestis. Results: Y. pestis employs a distinct mechanism indicating that CRP has no regulatory effect on the ompR-envZ operon; however, it stimulates ompC and ompF directly, while repressing ompX. No transcriptional regulatory association between CRP and its own gene can be detected in Y. pestis, which is also in contrast to the fact that CRP acts as both repressor and activator for its own gene in E. coli. It is likely that Y. pestis OmpR and CRP respectively sense different signals (medium osmolarity, and cellular cAMP levels) to regulate porin genes independently. Conclusion: Although the CRP of Y. pestis shows a very high homology to that of E. coli, and the consensus DNA sequence recognized by CRP is shared by the two bacteria, the Y. -

Fluorescence Spectroscopic Analysis of Ppgpp Binding to Camp Receptor Protein and Histone-Like Nucleoid Structuring Protein

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Communication Fluorescence Spectroscopic Analysis of ppGpp Binding to cAMP Receptor Protein and Histone-Like Nucleoid Structuring Protein Taner Duysak 1 , Thanh Tuyen Tran 1 , Aqeel Rana Afzal 2 and Che-Hun Jung 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Molecular Medicine, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea; [email protected] (T.D.); [email protected] (T.T.T.) 2 Department of Medical Science, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemistry, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-62-530-3383 Abstract: The cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) is one of the best-known transcription factors, regulating about 400 genes. The histone-like nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) is one of the nucleoid-forming proteins and is responsible for DNA packaging and gene repression in prokaryotes. In this study, the binding of ppGpp to CRP and H-NS was determined by fluorescence spectroscopy. CRP from Escherichia coli exhibited intrinsic fluorescence at 341 nm when excited at 280 nm. The fluorescence intensity decreased in the presence of ppGpp. The dissociation constant of 35 ± 3 µM suggests that ppGpp binds to CRP with a similar affinity to cAMP. H-NS also shows intrinsic fluorescence at 329 nm. The fluorescence intensity was decreased by various ligands and the calculated dissociation constant for ppGpp was 80 ± 11 µM, which suggests that the binding site Citation: Duysak, T.; Tran, T.T.; was occupied fully by ppGpp under starvation conditions. This study suggests the modulatory Afzal, A.R.; Jung, C.-H. -

Glycine Cleavage System and Camp Receptor Protein Co-Regulate CRISPR/Cas3 Expression to Resist Bacteriophage

viruses Article Glycine Cleavage System and cAMP Receptor Protein Co-Regulate CRISPR/cas3 Expression to Resist Bacteriophage Denghui Yang 1, Zhaofei Wang 1, Jingjiao Ma 1 , Qiang Fu 1, Lifei Wu 1, Hengan Wang 1, Shaohui Wang 2, Yaxian Yan 1,* and Jianhe Sun 1,* 1 Shanghai Key Laboratory of Veterinary Biotechnology, Key Laboratory of Urban Agriculture (South), Ministry of Agriculture, School of Agriculture and Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China; [email protected] (D.Y.); [email protected] (Z.W.); [email protected] (J.M.); [email protected] (Q.F.); [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (H.W.) 2 Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shanghai 200241, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.Y.); [email protected] (J.S.); Tel.: +86-21-3420-6003 (Y.Y.); +86-21-3420-6926 (J.S.) Received: 5 December 2019; Accepted: 9 January 2020; Published: 13 January 2020 Abstract: The CRISPR/Cas system protects bacteria against bacteriophage and plasmids through a sophisticated mechanism where cas operon plays a crucial role consisting of cse1 and cas3. However, comprehensive studies on the regulation of cas3 operon of the Type I-E CRISPR/Cas system are scarce. Herein, we investigated the regulation of cas3 in Escherichia coli. The mutation in gcvP or crp reduced the CRISPR/Cas system interference ability and increased bacterial susceptibility to phage, when the casA operon of the CRISPR/Cas system was activated. The silence of the glycine cleavage system (GCS) encoded by gcvTHP operon reduced cas3 expression. -

Regulation and Function of the RPEL Protein – Phactr1 Maria Katarzyna

Regulation and function of the RPEL protein – Phactr1 Maria Katarzyna Wiezlak University College London and Cancer Research UK London Research Institute PhD Supervisor: Richard Treisman A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London May 2013 Declaration I Maria Wiezlak confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Part of the work was performed in collaboration. In Chapter 3, experiments presented in Figure 3.11 and parts of Figures 3.8, 3.10 and 3.15 were performed by Jessica Diring, a postdoc from the Transcription Laboratory at the London Research Institute. The structural analysis presented in Chapter 4 was performed in collaboration with Stephane Mouilleron, a postdoc from Neil McDonald’s Laboratory (Structural Biology Laboratory at the London Research Institute). Of the work presented, I was involved in initial optimisation of complex formation and initial screens. Stephane Mouilleron performed majority of the crystallisation screens and the optimisation work at the crystallisation stage, collected the X-ray diffraction data and solved the crystal structures. He also performed SEC- MALLS analysis of the complexes. Where analyses were performed by Stephane Mouilleron, this is indicated in the figure legends. In Chapter 5, experiments presented in parts of Figures 5.3, 5.4, 5.5 and 5.6 were performed by Jasmine Abella, a postdoc from Michael Way’s Laboratory (Cell Motility Laboratory at the London Research Institute). All other experiments presented in this thesis were performed by the author. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. -

Spot 42 RNA Mediates Discoordinate Expression of the E. Coli Galactose Operon

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 3, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Spot 42 RNA mediates discoordinate expression of the E. coli galactose operon Thorleif Møller, Thomas Franch, Christina Udesen, Kenn Gerdes, and Poul Valentin-Hansen1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Campusvej 55, DK-5230 Odense M, Denmark The physiological role of Escherichia coli Spot 42 RNA has remained obscure, even though the 109-nucleotide RNA was discovered almost three decades ago. Structural features of Spot 42 RNA and previous work suggested to us that the RNA might be a regulator of discoordinate gene expression of the galactose operon, a control that is only understood at the phenomenological level. The effects of controlled expression of Spot 42 RNA or deleting the gene (spf) encoding the RNA supported this hypothesis. Down-regulation of galK expression, the third gene in the gal operon, was only observed in the presence of Spot 42 RNA and required growth conditions that caused derepression of the spf gene. Subsequent biochemical studies showed that Spot 42 RNA specifically bound at the galK Shine-Dalgarno region of the galETKM mRNA, thereby blocking ribosome binding. We conclude that Spot 42 RNA is an antisense RNA that acts to differentially regulate genes that are expressed from the same transcription unit. Our results reveal an interesting mechanism by which the expression of a promoter distal gene in an operon can be modulated and underline the importance of antisense control in bacterial gene regulation. [Key Words: Antisense RNA; galactose operon; riboregulation; small RNAs; Spot 42RN A; translational regulation] Received March 22, 2002; revised version accepted May 13, 2002. -

Regulatory Roles for Small Rnas in Bacteria Eric Masse´ , Nadim Majdalani and Susan Gottesman

120 Regulatory roles for small RNAs in bacteria Eric Masse´ , Nadim Majdalani and Susan Gottesmanà Small RNAs can act to regulate both the synthesis of proteins, by scription termination, rather than interfering with the affecting mRNA transcription, translation and stability, and the translation of the replication protein. Cis-encoded anti- activity of specific proteins by binding to them. As a result of sense RNAs can also act as antitoxins, as in the Sok RNA recent genome-wide screens, around 50 small RNAs have now of plasmid R1 that affects the translation of the open been identified in Escherichia coli. These include many that reading frame (ORF) situated just upstream of the Hok require the RNA-binding protein Hfq for their activity; most of toxin protein, ultimately interfering with the translation these RNAs act by pairing with their target mRNAs. Small RNAs of Hok itself (reviewed in [3]). can both positively and negatively regulate translation, can simultaneously regulate multiple mRNA targets, and can change The recent increased recognition of important regulatory the pattern of polarity within an operon. roles for small RNAs encoded far from their targets (trans- acting), acting on multiple targets, or both, has expanded Addresses interest in how to find such regulatory RNAs and how Laboratory of Molecular Biology, National Cancer Institute, they work. In this review, we focus on the recent progress Bethesda, MD 20892, USA that has been made in finding and understanding this ÃCorrespondence: S Gottesman e-mail: [email protected] class of chromosomally-encoded small regulatory RNAs. Finding small RNAs Current Opinion in Microbiology 2003, 6:120–124 The first small RNAs, including 6S and Spot 42, were discovered 30 years ago. -

Gene Regulation in the Lac Operon

GENE REGULATION IN THE LAC OPERON by Kathryn Grace Patterson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana July, 2009 c Copyright by Kathryn Grace Patterson 2009 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a dissertation submitted by Kathryn Grace Patterson This dissertation has been read by each member of the dissertation committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citations, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to the Division of Graduate Education. Dr. Tom´aˇsGedeon Approved for the Department of Mathematical Sciences Dr. Kenneth L. Bowers Approved for the Division of Graduate Education Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a doc- toral degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. I further agree that copying of this dissertation is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with \fair use" as pre- scribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for extensive copying or reproduction of this dissertation should be referred to ProQuest Information and Learning, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106, to whom I have granted \the exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my dissertation in and from microform along with the non-exclusive right to reproduce and distribute my abstract in any format in whole or in part." Kathryn Grace Patterson July, 2009 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Tom´aˇsGedeon for his guidance, support and all of the opportunities he has provided. -

The Camp Receptor Protein CRP Can Function As an Osmoregulator of Transcription in Escherichia Coli

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 26, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The cAMP receptor protein CRP can function as an osmoregulator of transcription in Escherichia coli Lenore Landis,1,4 Jimin Xu,3,4 and Reid C. Johnson1,2,5 1Department of Biological Chemistry, School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095-1737 USA; 2Molecular Biology Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California 90095 USA Transcription of the P1 promoter of the Escherichia coli proP gene, which encodes a transporter of osmoprotectants, is strongly induced by a shift to hyperosmotic media. Unlike most other osmotically regulated promoters, the induction occurs for a brief period of time, corresponding to the replacement of intracellular K+ glutamate with osmoprotecting compounds. This burst of proP transcription is correlated with the osmolarity-dependent binding of the cAMP receptor protein CRP to a site within the proP P1 promoter. We show that CRP–cAMP functions as an osmotically sensitive repressor of proP P1 transcription in vitro. Binding of CRP to the proP promoter in vivo is transiently destabilized after a hyperosmotic shift with kinetics that correspond to the derepression of transcription, whereas Fis and Lac repressor binding is not osmotically sensitive. Similar osmotic regulation of proP P1 transcription by the CRP* mutant implies that binding of cAMP is not responsible for the unusual osmotic sensitivity of CRP activity. Osmotic regulation of CRP activity is not limited to proP. Activation of the lac promoter by CRP is also transiently inhibited after an osmotic upshift, as is the binding of CRP to the gal⌬4 P1 promoter. -

Small RNA Functions in Carbon Metabolism and Virulence of Enteric Pathogens

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector REVIEW ARTICLE published: 15 July 2014 CELLULAR AND INFECTION MICROBIOLOGY doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00091 Small RNA functions in carbon metabolism and virulence of enteric pathogens Kai Papenfort 1* and Jörg Vogel 2 1 Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA 2 RNA Biology Group, Institute for Molecular Infection Biology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Edited by: Enteric pathogens often cycle between virulent and saprophytic lifestyles. To endure these Thomas Dandekar, University of frequent changes in nutrient availability and composition bacteria possess an arsenal Würzburg, Germany of regulatory and metabolic genes allowing rapid adaptation and high flexibility. While Reviewed by: numerous proteins have been characterized with regard to metabolic control in pathogenic Michael Shapira, University of California, Berkeley, USA bacteria, small non-coding RNAs have emerged as additional regulators of metabolism. Petra Dersch, Helmholtz Center for Recent advances in sequencing technology have vastly increased the number of candidate Infection Research, Germany regulatory RNAs and several of them have been found to act at the interface of bacterial *Correspondence: metabolism and virulence factor expression. Importantly, studying these riboregulators Kai Papenfort, Department of has not only provided insight into their metabolic control functions but also revealed new Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Washington Road, mechanisms of post-transcriptional gene control. This review will focus on the recent Princeton, NJ 08544, USA advances in this area of host-microbe interaction and discuss how regulatory small RNAs e-mail: [email protected] may help coordinate metabolism and virulence of enteric pathogens. -

Regulation of Crp Transcription by Oscillation Between Distinct Nucleoprotein Complexes

The EMBO Journal Vol.17 No.10 pp.2877–2885, 1998 Regulation of crp transcription by oscillation between distinct nucleoprotein complexes Gardenia Gonza´ lez-Gil1–4, Regine Kahmann1,2 (Ullmann and Danchin, 1983; Ishizuka et al., 1993; Kolb and Georgi Muskhelishvili2 et al., 1993). In addition, the cAMP–CRP complex participates in 1Institut fu¨r Genbiologische Forschung Berlin GmbH, Ihnestrasse 63, the regulation of a large number of other processes in 2 D-14195 Berlin and Institut fu¨r Genetik der Universita¨tMu¨nchen, E.coli. It mediates activation of genes whose expression Maria Wardstrasse 1a, D-80638 Mu¨nchen, Germany is necessary for the metabolism of some amino acids 3 Present address: 635 Old Quarry Road North, Larkspur, CA 94939, (tnaA, ilvB, etc., Friden et al., 1982; Ullmann and Danchin, USA 1983), for the metabolism of nucleic acids (deo, cdd, etc., 4Corresponding author Ullmann and Danchin, 1983) and the synthesis of some e-mail: [email protected] membrane proteins (ompA and ompF, Scott and Harwood, 1980). Furthermore, cAMP–CRP is reported to be a FIS belongs to the group of small abundant DNA- repressor of its own transcription (Aiba, 1983; Cossart binding proteins of Escherichia coli. We recently and Gicquel-Sanzey, 1985; Okamoto and Freundlich, 1986; demonstrated that, in vivo, FIS regulates the expression Hanamura and Aiba, 1991), of genes for adenylate cyclase of several genes needed for catabolism of sugars and (Majerfeld et al., 1981; Mori and Aiba, 1985), of genes nucleic acids, a majority of which are also transcrip- encoding enzymes participating in glutamine metabolism tionally regulated by cAMP–cAMP-receptor protein (Prusiner et al., 1972) and of genes for the outer membrane (CRP) complex.