STRATEGIC STONE STUDY a Building Stone Atlas of SOMERSET & EXMOOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

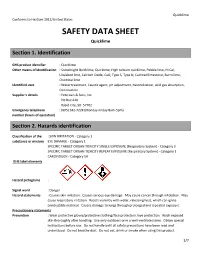

SAFETY DATA SHEET Quicklime

Quicklime Conforms to HazCom 2012/United States SAFETY DATA SHEET Quicklime Section 1. Identification GHS product identifier : Quicklime Other means of identification : Snowbright Quicklime, Quicklime, High calcium quicklime, Pebble lime, Hi Cal, Unslaked lime, Calcium Oxide, CaO, Type S, Type N, Calcined limestone, Burnt lime, Chemical lime Identified uses : Water treatment, Caustic agent, pH adjustment, Neutralization, Acid gas absorption, Construction Supplier's details : Pete Lien & Sons, Inc. PO Box 440 Rapid City, SD 57702 Emergency telephone : (605) 342-7224 (Monday-Friday 8am-5pm) number (hours of operation) Section 2. Hazards identification Classification of the : SKIN IRRITATION - Category 2 substance or mixture EYE DAMAGE - Category 1 SPECIFIC TARGET ORGAN TOXICITY SINGLE EXPOSURE [Respiratory System] - Category 3 SPECIFIC TARGET ORGAN TOXICITY REPEAT EXPOSURE [Respiratory System] - Category 1 CARCINOGEN - Category 1A GHS label elements Hazard pictograms : Signal word : Danger Hazard statements : Causes skin irritation. Causes serious eye damage. May cause cancer through inhalation. May cause respiratory irritation. Reacts violently with water, releasing heat, which can ignite combustible material. Causes damage to lungs through prolonged and repeated exposure. Precautionary statements Prevention : Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/face protection /eye protection. Wash exposed skin thoroughly after handling. Use only outdoors or in a well-ventilated area. Obtain special instructions before use. Do not handle until all safety precautions have been read and understood. Do not breathe dust. Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. 1/7 Quicklime Response : IF ON SKIN: Wash exposed skin with plenty of water. If skin irritation occurs: Get medical attention. Take off contaminated clothing and wash it before reuse. -

Specialists Q & a on the Use of Lime Plastering

posed to much less water making it less reactive but retaining its dry nature as a powdered product so it Q To avoid shrinkage, should hair be added to never matures to become a good binder in its own the lime mix? form. Hydrate is used as a plasticiser for cement Hair is added to help lime mortars bind or hold mixes. Hydraulic lime is a powder and also burnt A but the limestone is not pure calcium carbonate onto laths but can still shrink and crack if cured too Specialists Q & A on the and contains impurities such as clays and silicates quickly. Hair is always used on lath and plaster work which change the reactive nature of the lime and but is not necessary on brickwork. use of lime plastering allow it to set chemically when exposed to water. Q How do l make a lime wash? Q What type of lime should be used for lime A Lime wash is simply lime putty, water and a mineral pig- plastering? Q What are the advantages of using lime plas- ment, and for external use a water repellent such as linseed or tallow is added. ter? A Lime plaster can be made with lime putty or hydraulic lime but hydrate is too weak. Putty is best Q Can lime plaster be applied to plasterboard? A They allow buildings to breathe which is essential for ceilings and lath work as it has better flexural for older buildings that have been constructed with strength and sticks well to laths. Hydraulic lime is A The only benefit to applying a lime plaster to lime fine as a hard wall plaster where there is no move- plasterboard is the aesthetic look, however this mortars and soft bricks or stone. -

G Refs Atlas2020.Pdf

REFERENCES REFERENCES G. REFERENCES Fastnet Basin, offshore southwest Ireland. Journal of Micropalaeontology, 5, 19-29. AINSWORTH, N. R. & RILEY, L. A. 2010. Triassic to Middle Jurassic stratigraphy of the Kerr McGee 97/12-1 exploration ABBOTTS, I. 1991. United Kingdom oil and gas fields, 25 years commemorative volume. Memoir of the Geological Society well, offshore southern England. Marine & Petroleum Geology, 27, 853-894. of London, No.14. AINSWORTH, N. R., HORTON, N. F. & PENNEY, R. A. 1985. Lower Cretaceous micropalaeontology of the Fastnet ACTLABS. 2018. Report on 10 Ar-Ar analyses carried out as part of project IS16/04. IS16_04_ActLabs_raddatingrpt_Ar- Basin, offshore southwest Ireland. Marine & Petroleum Geology, 2, 341-349. Ar.xlsx. [Copy included within the Digital Addenda of this Atlas] AINSWORTH, N. R., BAILEY, H. W., GUEINN, K. J., RILEY, L. A., CARTER, J. & GILLIS, E. 2014. Revised AGNINI, C., FORNACIARI, E., RAFFI, I., CATANZARITI, R., PÄLIKE, H., BACKMAN, J. & RIO, D. 2014. stratigraphic framework of the Labrador Margin through integrated biostratigraphic and seismic interpretation, Biozonation and biochronology of Paleogene calcareous nannofossils from low and middle latitudes. Newsletters on Offshore Newfoundland and Labrador. Abstracts of the 4th Atlantic Conjugate Margins Conference. Go Deep: Back Stratigraphy, 47/2, 131–181. to the Source, 89-90. AINSWORTH, N. R. 1985. Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous Ostracoda from the Fastnet Basin, offshore southwest AINSWORTH, N. R., BRAHAM, W., GREGORY, F. J., JOHNSON, B & KING, C. 1998a. A proposed latest Triassic to Ireland. Irish Journal of Earth Sciences. 7, 15-33. earliest Cretaceous microfossil biozonation for the English Channel and its adjacent areas. -

The Mill Cottage the Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles

The Mill Cottage The Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles • 4.2 Acres • Stable Yard • Mill Leat & Stream • Parkland and Distant views • 3 Reception Rooms • Kitchen & Utility • 3 Bedrooms (Master En-Suite) • Garden Office Guide price £650,000 Situation The Mill Cottage is situated in the picturesque hamlet of Cockercombe, within the Quantock Hills, England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This is a very attractive part of Somerset, renowned for its beauty, with excellent riding, walking and other country pursuits. There is an abundance of footpaths and bridleways. The village of Nether Stowey is 2 miles away and Kingston St A charming Grade II Listed cottage with yard, stabling, 4.2 Acres of Mary is 5 miles away. Taunton, the County Town of Somerset, is some 8 miles to the South. Nether Stowey is an attractive centre land and direct access to the Quantock Hills. with an extensive range of local facilities, which are further supplemented by the town of Bridgwater, some 8 miles to the East. Taunton has a wide range of facilities including a theatre, county cricket ground and racecourse. Taunton is well located for national communications, with the M5 motorway at Junction 25 and there is an excellent intercity rail service to London Paddington (an hour and forty minutes). The beautiful coastline at Kilve is within 15 minutes drive. Access to Exmoor and the scenic North Somerset coast is via the A39 or through the many country roads in the area. The Mill Cottage is in a wonderful private location in a quiet lane, with clear views over rolling countryside. -

Minutes of Committee Meeting 10 October

Quantock Orienteers – Minutes of Committee Meeting 10 October 2018 at 67 Staplegrove Road, Taunton 19.15 start. 1.1 Attendees: Roger Craddock (Chairman), Rosie Wych, Judy Craddock, Steve Robertson, Bill Vigar, Chris Hasler, Matt Carter, Karen Lewis, Bob Lloyd. Apologies: Jeff Pakes. 2.1 Minutes of previous meeting approved 2.2 Matters arising: ACTION – UPDATE CONTACT DETAILS FOR COMMITTEE – RW -DONE ACTION – COMPLETE SPORT ENGLAND EVALUATION – SR - DONE ACTION – FORWARD JOG FIXTURE LIST TO SCHOOLS IN FOR START OF AUTUMN TERM – JC - DONE ACTION – CONTACT MEMBERS RE ENTRIES/TRANSPORT CS FINAL – CH - DONE ACTION – BOOK BROOMFIELD VILLAGE HALL –SR/RC -DONE ACTION – UPDATE WEBSITE FO CLUB CHAMPS–MC - DONE ACTION – CHECK EVENT PLAN DETAILS AND PERSONNEL – JC/RC - DONE ACTION – APPROACH TONY HEXT TO ACT AS BACK UP CONTROLLER FOR QOFL 3JC – Tony has informally agreed ACTION – PERMISSIONS FOR GALOPPEN – BL – See below ACTION – PROGRESS SOCIAL EVENING IDEA – CONTACT VIKKI PAGE AND TONY MILROY RW - ONGOING ACTION – PRODUCE MEMBERSHIP JOB SPECIFICATION – JR – KL now has understanding of role ACTION – SET UP REGISTER TO LOG NON MEMBER ATTENDANCE AND CONTACT INDIVIDUALS –KL (JR) – DONE/ONGOING –See membership report 3.1 Finance Report – see attached SR noted benefit of financial contributions from SASP etc. to help offset expenditure items like the 686 coaching fees payment. Even with QOFL 1 takings there is a negative balance on the accounts for the year. SR suggested a review of event finances at the end of the 2018/9 season. Confirm agreed event fees as: 2018 Event Charges QOFL GALOPPEN Members Non members Adult 7 10 10 12 Non comp. -

Somerset. North .Petherton• 353

DIRECTORY.] SOMERSET. NORTH .PETHERTON• 353 .san<\ and clay, and the subsoil is clay. The chief crops Post, S. B. & Annuity &; Insurance Office.-William Are wheat, barley and pasture. The area is 1,233 acres; James Plowman, sub-postmaster. Letters from Crew- rateable value, £2,482; the population in l€gI was 2g1. kerne arrive at 8 a.m. & < p.m.; dispatched at 9.30 Parish Clerk, Arthur Wilmott. a.m. & 5·35 p.m Nati~nal School (mixed), erected in 1846, for 60 children; Post, M. O. &, T. 0., T. ~I. 0., Express Delivery, Parcel average attendance, 50; Miss Harriett E. Barrett, mist iBrowne Miss, Bowling green Broughton Jas. farmer,Down Close fm Slade George & Anthony. farmers & Hobbs Mrs. The Cottage Dare Thos. & EH, farmers, Syme's fro butchers, Manor farm Hoskyns Rev. Charles Thomas M.A. Gear Benjamin, gardener to H. Wm. Slade Fred, blacksmith (rector), Rectory Hoskyns esq Slade Thomas, farmer, Townsend Hoskyns Henry William J.P. North Gear John, groeer & baker Slade William Henry, estate agen~ for Perr.)tt manor Gear Robert, shoe maker W. H. Hoskyns esq. & over&eer Hoskyns Henry William Paget J.P. Hewlett Frands, general dealer Symes Eli, Manor Arms P.H.; good North Perrott manor North Perrott Male & Female Benefit accommodation for tourists & Slade The Misses, Fernleigh cottage Society (W. H. Slade, hon. I!lec) cyclists Perry Charles, thatcher Tucker Thos. householder, Begonia col; COMMERCIAL. Plowman Wm. Jas. grocer, Post office Woodward John, farmer 13roughton Benj. dairyman,Grey Abbey Retter William, dairyman, Manor frm :NORTH PETHERTON is a large viIJage and parish, House, West Monkton. -

A Mysterious Giant Ichthyosaur from the Lowermost Jurassic of Wales

A mysterious giant ichthyosaur from the lowermost Jurassic of Wales JEREMY E. MARTIN, PEGGY VINCENT, GUILLAUME SUAN, TOM SHARPE, PETER HODGES, MATT WILLIAMS, CINDY HOWELLS, and VALENTIN FISCHER Ichthyosaurs rapidly diversified and colonised a wide range vians may challenge our understanding of their evolutionary of ecological niches during the Early and Middle Triassic history. period, but experienced a major decline in diversity near the Here we describe a radius of exceptional size, collected at end of the Triassic. Timing and causes of this demise and the Penarth on the coast of south Wales near Cardiff, UK. This subsequent rapid radiation of the diverse, but less disparate, specimen is comparable in morphology and size to the radius parvipelvian ichthyosaurs are still unknown, notably be- of shastasaurids, and it is likely that it comes from a strati- cause of inadequate sampling in strata of latest Triassic age. graphic horizon considerably younger than the last definite Here, we describe an exceptionally large radius from Lower occurrence of this family, the middle Norian (Motani 2005), Jurassic deposits at Penarth near Cardiff, south Wales (UK) although remains attributable to shastasaurid-like forms from the morphology of which places it within the giant Triassic the Rhaetian of France were mentioned by Bardet et al. (1999) shastasaurids. A tentative total body size estimate, based on and very recently by Fischer et al. (2014). a regression analysis of various complete ichthyosaur skele- Institutional abbreviations.—BRLSI, Bath Royal Literary tons, yields a value of 12–15 m. The specimen is substantially and Scientific Institution, Bath, UK; NHM, Natural History younger than any previously reported last known occur- Museum, London, UK; NMW, National Museum of Wales, rences of shastasaurids and implies a Lazarus range in the Cardiff, UK; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, lowermost Jurassic for this ichthyosaur morphotype. -

GEOLOGY of the ROANOKE and STEWARTSVILLE QUADRANGLES, VIRGINIA by Mervin J

VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 34 GEOLOGY OF THE ROANOKE AND STEWARTSVI LLE OUADRANG LES, VI RG I N IA Mervin J. Bartholomew COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVI LLE, VIRGI NIA 1 981 VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 34 GEOLOGY OF THE ROANOKE AND STEWARTSVI LLE OUADRANG LES, VI RG I N IA Mervin J. Bartholomew COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 1 981 FRONT COVER: Fold showing slightly fanned, axial plane, slaty cleav- age in a loose block of Liberty Hall mudstone at Reference Locality 20, Deer Creek, Roanoke quadrangle. REFERENCE: Portions of this publication may be quoted if credit is given to the Virginia Division of Mineral Resources. It is recommended that referenee to this report be made in the following form: Bartholomew, M. J., 1981, Geology of the Roanoke and Stewaitsville quadrangles, Vir- ginia, Vlrginia Division of Mineral Resources Publicatio4 34,23 p. VIRGINIA DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION 34 GEOLOGY OF THE ROANOKE AND STEWARTSVI LLE OUADRANG LES, VIRG I N IA Mervin J. Bartholomew COM MONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DIVISION OF MINERAL RESOURCES Robert C. Milici, Commissioner of Mineral Resources and State Geologist CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRG INIA 1 981 DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Richmond, Virginia FRED W. WALKER, Director JERALD F. MOORE, Deputy Director BOARD ARTHUR P. FLIPPO, Doswell, Chairman HENRY T. -

Download Download

. Oolites in the Green River Formation of Central Utah, and the Problem of Oolite Growth Stuart L. Schoff, DePauw University Oolitic limestone occurs in the Green River formation, of Eocene age, at Manti, in central Utah. A microscopic study of thin sections of the rock suggests conditions under which the oolite originated. As described by Bradley (1), and others, the Green River formation was deposited in a great fresh-water lake, or several lakes—an environ- ment contrasting strongly with the highly saline environment of Great Salt Lake, where oolitic grains are now forming, and less strongly with the marine conditions under which many oolites of the geologic column probably originated. Description.—The oolites are composed of calcium carbonate, chiefly as calcite, with an admixture of silt. Some of the material has been recrystallized, and some is now silicified. The average diameter of the grains is between 0.4 and 0.5 mm. They are circular in cross-section, elongate or oval, triangular, and irregular. In general, the outline con- forms with the shape of the nucleus, if one is present, but there are grains in which the outer zones are eccentric (Fig. 1, A) Uncommonly the oolitic grains contain mineral fragments as nuclei, but, even under high magnification, the centers of most of the grains appear simply as structureless spherical bodies of the same material as the rest of the grain. Hence the nuclei suggest little as regards causes for precipitation of calcium carbonate. Figure 1, B and Figure 2 illustrate grains with two centers of growth. One grain with three centers was noted. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Somerset. [ Kelly's

716 MAR SOMERSET. [ KELLY'S MARKET GARDENERs--continued. Duddridge W. Nth.Newton,Bridgwtr Kitchen M. Walton.in-Gordano,Clvdni Atherton In. North Weston, Clevedn Durbin John, Cheddar R.S.O Large George, 4 Stanbridge place,. Bacon Miss Mary, WaIton-in-Gor- Durbin Samuel, NaiIsea, Bristol Batheaston, Ba,th dano, Clevedon Durbin William, Cheddar RS.O Laverton Hy. 37 Vallis way, Frome Baker Mi.ss Annie, Nailsea, Brrstol DurmanGeorge, Moorsherd, North Lloyd J. The Hill, Langport R.S.O Baker Charles, Tickenham, Nailsea. Petherton, Bridgwater Mar,sh In. Benedict st. Glastonbury Baker John, Tickenham, Nailsea Durman Henry, Spanish hill, North MarshaII Wm. In. Henlade, TauntOn! Baker Thomas, Sandford, Bristol 'Petherton, Bridgwater Marshall Wm. F. Wrington, Bristol Bartlet F. WorIe, Wes,ton-super.Mare Eason George, Merriott 8.0 Martin Edwd. H. Batheaston, Bath Bennett John, Rydon, North Pether. Edmonds George, Grove cottage, Martin Richard, Sydney cottage, ton, Bridgwater Charlcombe, BathSmallcombe, Horse Shoe rd. Bath,) Bennett Thomas, Bankland, North Ellis Albert, West Coker~ Yeovil Maynard T. 'Chilton Trinity, Brdgwtr Petherton, Bridgwa,ter Escott Isaac, Newton rd. North Peth- Melluish William James, Bailbrook. Bishop Gllorge Hacker, Milton, Wes- erton, Bridgwater gardens, Batheaston, Bath ton-super-Mare Evans William, Cheddar R.S.O Minty Mrs. Emily, Ghilcompton, Bath-. Biss .!fUd. In. Long Ashton, Bristol Every Wm.North end,Batheaston,Bth Mitchel Reuben, Merriott S.O Biss John, IS King street, Frome Evry Henry, St. Catherine, Bath Mitchell William, Merriott S.O Blackmore John, Bower Ashton, Long Evry Mrs. Mary, Radford farm, Moxham James, Tickenham, Nailseal Ashton, Bristol Batheaston, Bath Nicholls W. West Chinnock, Seaving- Bond Samuel, Moon lane, North Peth- Evry Thomas, Avonland cottage,Bath. -

'Cenoceras Islands' in the Blue Lias Formation (Lower Jurassic)

FOSSIL IMPRINT • vol. 75 • 2019 • no. 1 • pp. 108–119 (formerly ACTA MUSEI NATIONALIS PRAGAE, Series B – Historia Naturalis) ‘CENOCERAS ISLANDS’ IN THE BLUE LIAS FORMATION (LOWER JURASSIC) OF WEST SOMERSET, UK: NAUTILID DOMINANCE AND INFLUENCE ON BENTHIC FAUNAS DAVID H. EVANS1, *, ANDY H. KING2 1 Stratigrapher, Natural England, Rivers House, East Quay, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 4YS UK; e-mail: [email protected]. 2 Director & Principal Geologist, Geckoella Ltd, Suite 323, 7 Bridge Street, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 1TG UK; e-mail: [email protected]. * corresponding author Evans, D. H., King, A. H. (2019): ‘Cenoceras islands’ in the Blue Lias Formation (Lower Jurassic) of West Somerset, UK: nautilid dominance and influence on benthic faunas. – Fossil Imprint, 75(1): 108–119, Praha. ISSN 2533-4050 (print), ISSN 2533-4069 (on-line). Abstract: Substantial numbers of the nautilid Cenoceras occur in a stratigraphically limited horizon within the upper part of the Lower Jurassic (Sinemurian Stage) Blue Lias Formation at Watchet on the West Somerset Coast (United Kingdom). Individual nautilid conchs are associated with clusters of encrusting organisms (sclerobionts) forming ‘islands’ that may have been raised slightly above the surrounding substrate. Despite the relatively large numbers of nautilid conchs involved, detailed investigation of their preservation suggests that their accumulation reflects a reduction in sedimentation rates rather than an influx of empty conches or moribund animals. Throughout those horizons in which nautilids are present in relative abundance, the remains of ammonites are subordinate or rare. The reason for this unclear, and preferential dissolution of ammonite conchs during their burial does seem to provide a satisfactory solution to the problem.