The Provision of Books for Church Use in the Deanery of Dunwich, 1370

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

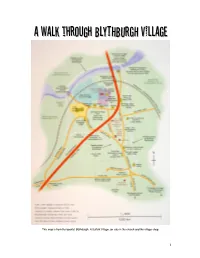

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

To Blythburgh, an Essay on the Village And

AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) Alan Mackley Blythburgh 2020 AN INDEX to M. Janet Becker, Blythburgh. An Essay on the Village and the Church. (Halesworth, 1935) INTRODUCTION Margaret Janet Becker (1904-1953) was the daughter of Harry Becker, painter of the farming community and resident in the Blythburgh area from 1915 to his death in 1928, and his artist wife Georgina who taught drawing at St Felix school, Southwold, from 1916 to 1923. Janet appears to have attended St Felix school for a while and was also taught in London, thanks to a generous godmother. A note-book she started at the age of 19 records her then as a London University student. It was in London, during a visit to Southwark Cathedral, that the sight of a recently- cleaned monument inspired a life-long interest in the subject. Through a friend’s introduction she was able to train under Professor Ernest Tristram of the Royal College of Art, a pioneer in the conservation of medieval wall paintings. Janet developed a career as cleaner and renovator of church monuments which took her widely across England and Scotland. She claimed to have washed the faces of many kings, aristocrats and gentlemen. After her father’s death Janet lived with her mother at The Old Vicarage, Wangford. Janet became a respected Suffolk historian. Her wide historical and conservation interests are demonstrated by membership of the St Edmundsbury and Ipswich Diocesan Advisory Committee on the Care of Churches, and she was a Council member of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. -

Blything Hundred Assessment for the First Payment

Blything Hundred assessment for the first payment (to be rated by 20 May 1642) of a grant under An Act for the raising and leavying of Moneys for the necessary defence and great affaires of the Kingdomes of England and Ireland and for the payment of debts undertaken by the Parliament (16 Charles I chapter 32) This index comprises: images of the original parchment roll (E1/25) from SRO Bury St Edmunds; Vincent B. Redstone's transcript (HD11/1 : 4921/10.14) photographed at SRO Ipswich; Redstone's 1904 book, The Ship-Money Returns for the County of Suffolk, 1639-40 (Harl. MSS. 7,540–7,542), which lacks about half the parishes of Blything Hundred. Original roll Vincent B. Redstone's transcript Ship Money Sums due from county of Suffolk 18r c [0 verso] (facing folio 1 recto) & hundred of Blything VBR's notes re rents & Acts [0 verso] (facing folio 1 recto) Aldringham cum Thorpe 10r a 25 74 Benacre 08r a 18v - Blyford 10r a 26 85 Blythburgh 15r a 40v 75 Blythford - See Blyford Bramfield 12v a 33 78 Brampton 04r a 8v - Bulcamp [hamlet in Blythburgh] 15v a 41 (Blythburgh) 76 Buxlow - See Knodishall Chediston 06r a 14 76 Cookley 11r a 27v - Covehithe or North Hales 17r a 46 (Norhales al(ia)s Covehithe) - Cratfield 13r a 34v 79 Darsham 17r a 45 83 Dunwich 08v a 20v - Easton Bavents 04v a 10v - Frostenden 07v b Omitted by VBR - Halesworth 09r a 21v 81 Henham [hamlet in Wangford] 05v a 12v 75 Henstead 06v b 16v - Heveningham 01v a 2v 85 Holton [St Peter] 06r a 14v - Huntingfield 10v a 26v 78 Knodishall & Buxlow 16r a 43 73 Leiston & Sizewell 11v a 29v - Linstead Magna 16r b 43v 79 Linstead Parva 16v a 44 77 1 Blything Hundred assessment for the first payment (to be rated by 20 May 1642) of a grant under An Act for the raising and leavying of Moneys for the necessary defence and great affaires of the Kingdomes of England and Ireland and for the payment of debts undertaken by the Parliament (16 Charles I chapter 32) Original roll Vincent B. -

01986 896896 Bactcommunitytransport.Org.Uk

Community transport in Blundeston, Corton, Flixton (Lowestoft), Lound, Oulton and Somerleyton/Ashby/Herringfleet bact community transport runs the following services in your area of Waveney district. The Connecting Bus Between 0930 and 1600 on Tuesdays, the Connecting Bus covers the following parishes: Blundeston, Corton, Flixton (Lowestoft), Lound, Lowestoft, Oulton, and Somerleyton /Ashby/Herringfleet. The Connecting Bus allows people to request any journey within the area above and anyone can use the service. Pick up is from a safe location near your home: a bus stop or the end of your road. Fares are similar to those on buses, under 20s have reduced fares and concessionary passes are valid after 0930. Door to door (formerly called Dial a Ride) Between 0930 and 1600 on Mondays to Fridays, the door to door service enables eligible registered members to request transport from their home to their final destination for journeys within these parishes Benacre, Blundeston, Carlton Colville, Corton, Covehithe, Flixton (Lowestoft), Frostenden, Gisleham, Kessingland, Lound, Lowestoft, Oulton, Reydon, Somerleyton/Ashby/Herringfleet, South Cove, Southwold, and Wrentham. Fares are reasonable but concessionary passes cannot be used. Community car service The car service operates up to seven days a week, depending on the availability of volunteer drivers who use their own vehicles. Anyone may ask to use the service to make journeys for which neither a car, nor public transport, is available. The fare is based on the distance travelled. The distance is from between the driver’s home to the place where you are picked up and on to your destination and back to the driver’s home. -

Suffolk County Council Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order

Lake Lothing Third Crossing Consultation Report Document Reference: 5.1 The Lake Lothing (Lowestoft) Third Crossing Order 201[*] _________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________ Document 5.2: Consultation Report Appendices Appendix 13 List of Non-statutory Consultees _________________________________________________________________________ Author: Suffolk County Council Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report appendices THIS PAGE HAS INTENTIONALLY BEEN LEFT BLANK 2 Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices Consultation Report Appendix 13 List of non-statutory consultees Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices THIS PAGE HAS INTENTIONALLY BEEN LEFT BLANK Lake Lothing Third Crossing Application for Development Consent Order Document Reference: 5.2 Consultation Report Appendices All Saints and St Forestry Commission Suffolk Advanced Motorcyclists Nicholas, St Michael and St Peter South Elmham Parish Council Ashby, Herringfleet and Freestones Coaches Ltd Suffolk Amphibian & Reptile Group Somerleyton Parish Council Barnby Parish Council Freight Transport Suffolk Archaeology Association Barsham & Shipmeadow Friends of Nicholas Suffolk Biological Records Centre Parish Council Everitt Park Beccles Town Council -

Nuclear Prospects’: the Siting and Construction of Sizewell a Power Station 1957-1966

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch ‘Nuclear prospects’: the siting and construction of Sizewell A power station 1957-1966. Wall, C. This is an accepted manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Contemporary British History. The final definitive version is available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13619462.2018.1519424 © 2018 Taylor & Francis The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] ‘Nuclear prospects’: the siting and construction of Sizewell A power station 1957-1966. Abstract This paper examines the siting and construction of a Magnox nuclear power station on the Suffolk coast. The station was initially welcomed by local politicians as a solution to unemployment but was criticised by an organised group of local communist activists who predicted how the restriction zone would restrict future development. Oral history interviews provide insights into conditions on the construction site and the social effects on the nearby town. Archive material reveals the spatial and development restrictions imposed with the building of the power station, which remains on the shoreline as a monument to the ‘atomic age’. This material is contextualised in the longer economic and social history of a town that moved from the shadow of nineteenth century paternalistic industry into the glare of the nuclear construction program and became an early example of the eclipsing of local democracy by the centralised nuclear state. -

England Coast Path Report 2 Sizewell to Dunwich

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: Aldeburgh to Hopton-on-Sea Report AHS 2: Sizewell to Dunwich Part 2.1: Introduction Start Point: Sizewell beach car park (grid reference: TM 4757 6300) End Point: Dingle Marshes south, Dunwich (grid reference: TM 4735 7074) Relevant Maps: AHS 2a to AHS 2e 2.1.1 This is one of a series of linked but legally separate reports published by Natural England under section 51 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which make proposals to the Secretary of State for improved public access along and to this stretch of coast between Aldeburgh to Hopton-on-Sea. 2.1.2 This report covers length AHS 2 of the stretch, which is the coast between Sizewell and Dunwich. It makes free-standing statutory proposals for this part of the stretch, and seeks approval for them by the Secretary of State in their own right under section 52 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. 2.1.3 The report explains how we propose to implement the England Coast Path (“the trail”) on this part of the stretch, and details the likely consequences in terms of the wider ‘Coastal Margin’ that will be created if our proposals are approved by the Secretary of State. Our report also sets out: any proposals we think are necessary for restricting or excluding coastal access rights to address particular issues, in line with the powers in the legislation; and any proposed powers for the trail to be capable of being relocated on particular sections (“roll- back”), if this proves necessary in the future because of coastal change. -

Fynn - Lark Ews May 2019

Fynn - Lark ews May 2019 HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS May is traditionally a month to enjoy the great outdoors in mild and fragrant weather. Whether that means looking for a romantic maypole to dance around, trying to stay ahead of the rapid garden growth or merely enjoying the longer days and busy birdsong, it is for some a month to get outside and appreciate the English countryside we have access to, right on our doorsteps. This year sees the 70th anniversary of the creation of our National Parks – not that we have one in easy reach in Suffolk – but the same legislation required all English Parish Councils to survey all their footpaths, bridleways and byways, as the start of the legal process to record where the public had a right of way over the countryside. Magazine for the Parishes of Great & Little Bealings, Playford and Culpho 1 2 On the Little Bealings Parish Council surveyor is the rather confusing: "A website are the survey sheets showing common law right to plough exists if the the Council carrying out this duty in 1951. landowner can show, or you know, that From the descriptions of where they he has ploughed this particular stretch of walked, many of the routes are easily path for living memory. Just because a identifiable, as the routes in use are path is ploughed out does not necessarily signed ‘Public Footpath’ today. The indicate a common law right to plough; Council was required to state the reason the ploughing may be unlawful. why it thought each route it surveyed was Alternatively, there may be a right to for the public to use. -

Cratfield News

CRATFIELD NEWS April 2019 1 Hello and Welcome A very warm welcome to Vanessa, Andrew, Will and John, who along with Eddie the dog have recently moved into no.6 The Street, Maddie Gallop now of 2 Boxbush Cottages and also to Nicky and Bruce who have come to live at Hill View on Bell Green. We hope they will be very happy here in Cratfield. THE VINTAGE TRACTORS ARE BACK! Once again, the annual vintage tractor run will stop at Cratfield vil- lage hall for tea and cakes before departing en masse. It's a spectacular sight! Arrival time for the convoy is approximately 12.30pm on Easter Monday, April 22 nd . The time could be a little earlier or later, depending on traffic as they muster at Flixton a few miles away. Everyone is welcome to come along and see them and to enjoy the refreshments, proceeds from which will go to St. Martin's Housing Trust. Please note they don't stay much above and hour in Cratfield. 2 Please think of pedestrians and do not park on the pavements in Cratfield! 3 Laxfield Produce, Craft and Flea Market Saturday 6 th April 9.30am -12.00pm inside All Saint's Church and in the Royal Oak, and outside on Church Plain The organisers of the Market have been really pleased with continued support from both stallholders and customers over the winter months, turnout has been very good despite at times doubtful weather conditions. The additional all -year - round opening has certainly proved very popular. No doubt an Easter theme will be heavily featured at April's Market, with it being just under two weeks away. -

8Ufj4'0lk. Aldringham

DIRECTORY.) 8UFJ4'0LK. ALDRINGHAM. 29 shells and fossils are numerous. The chief crops are Public Elementary School (mixed), erected in I858, for wheat and barley. The area is lZ,575 acres; rateable So children; average attendance, 77; Miss lsabel value, £2,389; the population in I9II was 425· Bennett, mistress Parish Clerk, George Friend. Carrier to Woodbridge.-Frederick Claxon, daily Post, M. 0. & T. {).ffice.--'Miss Eliza G. Steward, sub postmistress. Letters received from W oodbridge at Police Station, George Garrod, constable in charge 5·55 & II.I5 a.m.; dispatched at 12.25 & 6.40 p.m Askin Thos. Cuming B.A.,B.Ch., M.D division, & medical officer,Warner"s .Mann Eliza (Mrs.), farmer Ellis Rev. Hy. Venn (rector), Rectory Almshouses Parker Robert George, grocer & drpr Kitchiner Stanley W. The Manse Claxon Frederick, carrier Sayers .Arthur J. grocer & draper Letts Sydney Edward, Cedar court Etnmens Henry, baker & farmer Smith Fred, pork butcher Stinson Mrs. Alderton lodge Foster William Isaac, Swan commer- Smith Jn. !brook, farmer,TheGrange Williama Emest Harcourt, Alderton cial inn & posting house; nearest Spall Arthur, wheelwright hall railway station, Felixstowe town, 6 Steward Eliza G. (Miss), grocer & COMMERCIAL. miles pGstmistress .Askin Thos.Cuming B.A.,B.Ch., M.D., Garrard William, butcher Thompson Frederick:, saddler surgeon, & medical officer & public Lacey Frederick Waiter, miller (wind Williams Ernest Harcourt, farmer, vaccinator, Nos. I & 2 districts, & steam) & threshing machine ownr .Alderton hall Woodbridge union & Admiralty sur- Lennard James, farmer & threshing Wingrave Louisa (Mrs.), Crown P.H geon &i agent, .Aldeburgh South machine ownell & landowner ALDHA:M is a parish and village 2! miles north-by- in bread on St. -

522 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

522 bus time schedule & line map 522 Peasenhall - Saxmundham - Leiston - Aldeburgh View In Website Mode The 522 bus line (Peasenhall - Saxmundham - Leiston - Aldeburgh) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Aldeburgh: 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM (2) Leiston: 7:55 AM (3) Leiston: 2:50 PM (4) Peasenhall: 3:10 PM (5) Saxmundham: 8:20 AM - 5:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 522 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 522 bus arriving. Direction: Aldeburgh 522 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Aldeburgh Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM Saxon Road, Saxmundham Rendham Road, Saxmundham Tuesday 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM Heron Road, Saxmundham Wednesday 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM Long Avenue, Saxmundham Thursday 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM Shelley Mews, Saxmundham Friday 7:55 AM - 4:13 PM Ashfords Close, Saxmundham Saturday Not Operational Brook Farm Road, Saxmundham School, Saxmundham Felsham Rise, Saxmundham 522 bus Info Dove Close, Saxmundham Direction: Aldeburgh Stops: 29 The Limes, Saxmundham Trip Duration: 75 min Alde Close, Saxmundham Line Summary: Saxon Road, Saxmundham, Heron Road, Saxmundham, Long Avenue, Saxmundham, Lambsale Meadow, Saxmundham Ashfords Close, Saxmundham, School, Lambsale Meadow, Saxmundham Saxmundham, Felsham Rise, Saxmundham, The Limes, Saxmundham, Lambsale Meadow, Street Farm Road, Saxmundham Saxmundham, Street Farm Road, Saxmundham, Waitrose, Saxmundham, Manor Gardens, Waitrose, Saxmundham Saxmundham, Clay Hills, Leiston, St Margaret's Saxmundham Road, Saxmundham