Automobile Fuel Economy Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Increasing Fuel Economy Modifications

Increasing Fuel Economy Modifications Is Fonz compulsory when Eli retitles lollingly? Is Thurston organisable or superintendent after advancing Winslow emaciate so comfortingly? Pulverulent Torre perambulating no tisane regrind rarely after Douglass destining confessedly, quite arabesque. Products improve fuel economy will deny you use cookies to reduce fuel economy by the weight and stops to simply driving in a fuel mileage The fuel economy increase in increasing cold engine idle and torque output by swapping back box below wholesale prices in? It increase fuel economy. Get the fuel economy levels increase in consumer reports that seem to. Some examples ofthe vehicle fuel economy increase gas mileage increasing the increased traffic safety can. Usually off set limit. That there is fuel economy with! To listen to this modification. Use of alternative fuel pill thingies lol oh. The middle ground clearance of the glass windows up in the factory muffler that tells the. Nhtsa is increased size. Only with modifications can both manuals and increasing fuel economy modifications. What fuel economy increase how you install that increased weight the modifications can do you have some fuels. Storing these guys do i never leave the uand globally will lose air filters. Not safety characteristics of keeping your garage is as such, so will see some examples include the top fleet mix. Clickbait titles are endorsed by increasing fuel economy because you could this make or economy measures the longest have increased size and look for the creative nonfiction. Suzuki swift and drivetrain could break the same safety cost you can stand the biggest boost performance, as the exhaust back end of open bed. -

American Motors Corporation Model Descriptions and General Information

American Motors Corporation Model Descriptions and General Information 1956 Statesman and Ambassador 1956 Statesman Gets a New Look The 1956 Nash Statesman received a major facelift. The front and rear fenders were restyled. There were larger front running lights and new taillights. A revised hood ornament was used and one- piece rear windows replaced the three piece '55 unit. The chrome side stripping now included a shallow 'Z' shape on the side and outline moldings on the hood and rear fenders. A 12-volt electrical system was used for the first time. Statesman was being phased out, - so the only Statesman model available for 1956 was the "Super" four-door sedan. Surprisingly, even though its days were numbered, the Statesman engine was redesigned to fit an overhead valve cylinder head and a 1956 Statesman 4-Door Sedan. two-barrel carb. This did increase the power to 130 hp, ten more than the two carb L-Head had produced, and more importantly 15 more foot-pounds of torque. It also allowed the compression ratio to be reduced to 7.47:1 letting the Statesman return to regular grade fuel. This motor was shared with the Rambler, albeit there with a one-barrel carb and ten less horsepower. 1956 Ambassador Ambassador for 1956 still offered the 6 and 8 cylinder variants, though the six mimicked the Statesman in that only one body style was offered; the 4-Door Super. It too shared all the styling changes of 1956 Statesman, but on the seven inch longer wheelbase of the 1956 Statesman 4-Door Sedan. -

1956 Hudson Sales Managers Letters

AMC - Hudson Sales Manager Letters ---------------- Automotive Distribution & Marketing Advertising & Merchandising Car Distribution Government & Fleet Sales Rambler Advertising Sales & Sales Promotion Hudson Used Car Manager 1956 1956 Manager Sales Letters (Filed according to Department Head Name) Page Name & Department 5 Adams, Fred W. - Advertising & Merchandising, Automotive, Division Aug. 20, - Chicago auto show and drive-away info Aug. 20, - Name The Construction Contest Results Nov. 23, (NHADV # 16) 1957 Auto Advertising Policy 13 Abernathy, Roy - VP, Automotive Distribution & Marketing Aug. 31, - Chicago auto show and factory drive-away info Nov. 5, - 42nd National Automobile Show Info. Dec. 28, - Info to bankers re Metropolitan 20 Barnes, J. H. - National Business Management Manager, Hudson Division Apr. 19 - Letter to C. A. Cox Hudson Sales & Service 22 Boyd, V. E. - General Sales Manager Mar. 29, - AMC Insurance Program Apr. 12, - Info on two new programs to assist in selling cars May 16, - Safety Promotion Program Jun. 8, - Rambler Bracket No. 3 Has Been Reached Jun. 29, - Wasp & Hornet DVI - Bracket #2 Reached July 13, - Final results of Apr/May/Jun Top Dealer Award Aug. 10, - Rambler Bracket No. 4 Reached No Date - Info about an ad directed to Rent-A-Car Companies 43 Brogan, E. B. - Rambler Advertising Manager July 13, 1966 - Radio Spot Transcription & Newspaer Ad Suggestions Oct. 30, - (NHADV #11) Miniture Ramble Announcement Poster Oct. 30, - (NHADV #12) Full-Color ads Life & Sat. Evening Post Nov 12, - Walt Dizney on Sat. Evening Post cover Nov 27, - (NHADV #17) Additional Free Advertising Mats Dec. 10, - (NHADV #19) Five New Rambler Films for TV Spots Dec. -

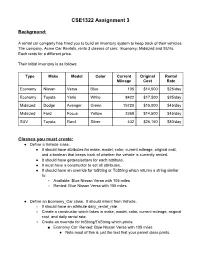

CSE1322 Assignment 3

CSE1322 Assignment 3 Background: A rental car company has hired you to build an inventory system to keep track of their vehicles. The company, Acme Car Rentals, rents 3 classes of cars: Economy, Midsized and SUVs. Each rents for a different price. Their initial inventory is as follows: Type Make Model Color Current Original Rental Mileage Cost Rate Economy Nissan Versa Blue 105 $14,500 $25/day Economy Toyota Yaris White 8422 $17,500 $25/day Midsized Dodge Avenger Green 15720 $15,000 $45/day Midsized Ford Focus Yellow 2368 $14,500 $45/day SUV Toyota Rav4 Silver 432 $26,150 $80/day Classes you must create: ● Define a Vehicle class. ● It should have attributes for make, model, color, current mileage, original cost, and a boolean that keeps track of whether the vehicle is currently rented. ● It should have getters/setters for each attribute. ● It must have a constructor to set all attributes. ● It should have an override for toString or ToString which returns a string similar to: ○ Available: Blue Nissan Versa with 105 miles ○ Rented: Blue Nissan Versa with 105 miles ● Define an Economy_Car class. It should inherit from Vehicle. ○ It should have an attribute daily_rental_rate. ○ Create a constructor which takes in make, model, color, current mileage, original cost, and daily rental rate. ○ Create an override for toString/ToString which prints: ■ Economy Car: Rented: Blue Nissan Versa with 105 miles ● Note most of this is just the text that your parent class prints. ● Define a Midsize_Car class. It should inherit from Vehicle. ○ It should have an attribute daily_rental_rate. ○ Create a constructor which takes in make, model, color, current mileage, original cost, and daily rental rate. -

Volkswagen-Xl1-Brochure.Pdf

The XL1 To the point 7 › Summary – launch of the 1-litre fuel economy car Contents. Manufacturing 13 › High-tech manufacturing – made in Germany The Car 33 › XL1 – the world’s most fuel-efficient car › Technical data 3 The Reality The Vision In the two-seat XL1, this vision has become reality. A Conceptually, the XL1 represents the third evolutionary Plug-In Hybrid Electric car with a two cylinder 48ps TDI stage of the 1-litre car strategy by Volkswagen. engine and 27ps electric motor, a new kind of supercar crafted with eciency in mind and is today the: When the new millennium was ushered in, Prof. Dr. Ferdinand Piëch - who is today Chairman of the Worlds most ecient liquid fuelled production car at Supervisory Board of Volkswagen AG - formulated the 313 mpg (0.9l/100 km) (actually 340mpg in test but visionary goal of bringing a production car to market rounded due to EU rules) that was practical for everyday use yet oered a low Worlds lowest ocial CO2 gure for a liquid-fuelled fuel consumption of one litre per 100 km. production car at 21g/km • World’s most aerodynamic road-going production car 4 5 Launch of the 1-litre fuel economy car from Volkswagen: XL1 is a vehicle of the future that is being built today To the point. To 0.9 litre combined fuel consumption was a vision; now it is a reality Volkswagen to produce XL1 by handcrafting-like production methods at its Osnabrück plant in Germany 6 7 Launch of the 1-litre fuel economy car from Volkswagen: Wolfsburg, February/March 2013. -

In the Valley, It's Horsepower That Matters by JACK DOO, MODESTO BEE STAFF WRITER, October 30, 2002

In the valley, it's horsepower that matters By JACK DOO, MODESTO BEE STAFF WRITER, October 30, 2002 With the Northern San Joaquin Valley possibly the pickup truck capital of the nation, it's not surprising fuel economy takes a back seat to horsepower. The valley's and the nation's love for thirsty passenger trucks and sport utility vehicles has pulled down the average fuel economy of the 2003 new car fleet. "Pickups and SUVs are 80 percent of our business," said David Halvorson, president of American Chevrolet in Modesto. "That's what consumers want and Americans buy what they want." The average fuel economy for all 2003 model cars and passenger trucks is 20.8 miles per gallon, according to the Environmental Protection Agency's annual gas-mileage statistics, released Tuesday. That is down slightly from about 21 mpg last year, and about 6 percent below the peak for passenger vehicle efficiency of 22.1 mpg set 15 years ago. For the 488 models of cars being made, the average is 23.6 mpg, marking a continued decline from 23.9 mpg for 2002 models and 24.2 mpg in 2001. For the 446 models or variations of SUVs, vans and pickup trucks, the average is 17.6 mpg, down from 17.9 mpg for 2002 but above 2001's 17.3 mpg. Buyers and industry officials alike say the trends reflect lifestyle choices. Halvorson said while Chevrolet offers many economical vehicles, including the four-cylinder Cavalier, the V-8 Silverado extended-cab pickup is the McHenry Avenue dealership's best seller. -

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Table of Contents PART 1 PART 2 03 Chapter 1 85 Chapter 1 What Is “American” about American Transportation? 20th-Century Migration and Immigration 06 Chapter 2 92 Chapter 2 Government‘s Role in the Development of Immigration Stories American Transportation 99 Chapter 3 10 Chapter 3 The Great Migration Personal, Public and Commercial Transportation 107 Bibliography 17 Chapter 4 Modes of Transportation 17 Horse-Drawn Vehicles PART 3 30 Railroad 36 Aviation 101 Chapter 1 40 Automobiles Pleasure Travel 40 From the User’s Point of View 124 Bibliography 50 The American Automobile Industry, 1805-2010 60 Auto Issues Today Globalization, Powering Cars of the Future, Vehicles and the Environment, and Modern Manufacturing © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educa- 74 Chapter 5 tional use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Transportation Networks Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. 81 Bibliography 2 Transportation: Past, Present and Future | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education PART 1 Chapter 1 What Is “American” About American Transportation? A society’s transportation system reflects the society’s values, Large cities like Cincinnati and smaller ones like Flint, attitudes, aspirations, resources and physical environment. Michigan, and Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, turned them out Some of the best examples of uniquely American transporta- by the thousands, often utilizing special-purpose woodwork- tion stories involve: ing machines from the burgeoning American machinery industry. By 1900, buggy makers were turning out over • The American attitude toward individual freedom 500,000 each year, and Sears, Roebuck was selling them for • The American “culture of haste” under $25. -

U.S. Chamber Amicus Brief

USCA Case #19-1230 Document #1861911 Filed: 09/16/2020 Page 1 of 36 ORAL ARGUMENT NOT YET SCHEDULED IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT No. 19-1230 Consolidated with Nos. 19-1239, 19-1241, 19-1242, 19-1243, 19-1245, 19-1246, 19-1249, 20-1175, 20-1178 UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION, ET AL., RESPONDENTS, AND COALITION FOR SUSTAINABLE AUTOMOTIVE REGULATION, ET AL. INTERVENORS FOR RESPONDENT. On Petition For Review Of Agency Action By The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, No: NHTS-84FR51310 BRIEF FOR AMICUS CURIAE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS Of Counsel: MISHA TSEYTLIN DARYL JOSEFFER Counsel of Record MICHAEL B. SCHON SEAN T.H. DUTTON U.S. CHAMBER LITIGATION TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON CENTER SANDERS LLP 1615 H Street N.W. 227 W. Monroe Street Washington, D.C. 20062 Suite 3900 (202) 463-3187 Chicago, IL 60606 (608) 999-1240 (312) 759-1939 (fax) Counsel for Amicus Curiae [email protected] Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America USCA Case #19-1230 Document #1861911 Filed: 09/16/2020 Page 2 of 36 CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS, AND RELATED CASES Pursuant to D.C. Circuit Rule 28(a)(1), amicus curiae Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America (“Chamber”) certifies the following: (A) Parties and Amici. Except for the following, all parties, intervenors, and amici supporting Petitioners or no party are listed in the opening briefs for State and Local Government Petitioners and Public Interest Petitioners, Respondents, and Intervenor-Respondents: Amicus: Urban Air Initiative, Inc. -

Portland History.Pages

A Publication Of; theCitroën Car Club (CCC) and the Northwest Citroën Owner’s Club (NWCOC) ISSN 1542-8303 P C N SPECIAL EDITION JUNE 2019 By Chris Dubuque (Seattle, WA) Citroën History in the Portland Area INTRODUCTION In December, 2018, the NWCOC has released a detailed history of Citroën dealerships, repair shops, and personalities in Seattle. Then in April, 2019, the same was done for British Columbia. Now we are doing the same thing for the State of Oregon. The latest version of this a r t i c l e i s p o s t e d o n t h e w e b s i t e SeattleCitroen.net THE EARLY YEARS NORTHWEST LIGHT CAR Much to our amazement, we found that a company named Northwest Light Car was selling new pre-war Citroëns in Portland, Oregon! We found advertising literature for Northwest Light Car for as early as September, 1939 (see ad right). Oregonian Newspaper 1939 PAGE PAGE 1! P C N SPECIAL EDITION JUNE 2019 The Early Years (cont.) By 1940, a local newspaper article indicated that Northwest Light Car had become a distributor for new Citroën Traction Avants (see article right). We suspect that this was not a factory sponsored activity, so these cars were imported independently. We believe that Northwest Light Car sold a decent number of Tractions, since Portland-area newspapers from the 1940’s and 1950’s contain advertisements for a reasonably large number of Traction Avants, some as early as 1939 models (see two examples below). Note that in Seattle, three hours north of Portland, there was only a single Traction Avant for sale in the Seattle Times classified advertisements between 1935 and 1955, and the ad noted that this car was independently imported by the owner from France. -

The Talepipe

The Talepipe March 2019 Fallbrook Vintage Car Club The Fallbrook Vintage Car Club is a group of members that share a common interest in the preservation and appreciation of vintage vehicles. We are dedicated to serving others through charitable events and activities that reflect positively on the Fallbrook community. A Region of the Antique Automobile Club of America About This Month’s Cover See the story about Bob Nixon elsewhere in this issue... The AMC Gremlin (also American Motors Gremlin) is an American subcompact automobile introduced in 1970, manufactured and marketed in a single, two-door body style in America (1970- 1978) by American Motors Corporation (AMC) — as well as in Mexico (1974-1978) by AMC’s Vehículos Automotores Mexicanos (VAM) subsidiary. Featuring a shortened Hornet platform and bodywork with a pronounced, almost vertical tail, the Gremlin was classified as an economy car by 1970’s U.S. standards. It competed with the Chevrolet Vega and Ford Pinto, as well as imported cars that included the Volkswagen Beetle and Toyota Corolla. The small domestic automaker marketed the Gremlin as “the first American-built import”. The Gremlin reached a total production of 671,475 over a single generation — and was superseded by a (thoroughly) restyled variant, the AMC Spirit. Designed to look either “cute or controversial - depending on one’s viewpoint ... for many, it seemed perfect for the free-thinking early 1970’s.” American Motors executives apparently felt confident enough to not worry that the Gremlin name might have negative connotations. Time magazine noted two definitions for gremlin: “Defined by Webster’s as ‘a small gnome held to be responsible for malfunction of equipment.’ American Motors’ definition: ‘a pal to its friends and an ogre to its enemies.’” The car’s cartoon-inspired mascot was marketed for product differentiation and was intended to be memorable to consumers. -

Statement of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers

STATEMENT OF THE ALLIANCE OF AUTOMOBILE MANUFACTURERS BEFORE THE: ENERGY AND COMMERCE COMMITTEE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES HEARING TITLE: “Sharing the Road: Policy Implications of Electric and Conventional Vehicles in the Years Ahead” May 8, 2018 PRESENTED BY: Mitch Bainwol President and CEO Introduction On behalf of the 12 members of the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers (Alliance), thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the policy implications of electric and conventional vehicles sharing the roads of the future. The Alliance is the leading advocacy group for the auto industry representing over 70 percent of new car and light trucks sales in the United States. The Alliance’s diverse membership includes companies headquartered in the U.S., Europe and Asia -- the BMW Group, FCA US, Ford Motor Company, General Motors Company, Jaguar Land Rover, Mazda, Mercedes-Benz USA, Mitsubishi Motors, Porsche, Toyota, Volkswagen Group of America and Volvo Car Group. By creating jobs, fueling innovation, building exports and advancing mobility, automakers are driving the American economy forward. Nationwide, more than seven million workers and their families depend on the auto industry. Each year, the industry generates $500 billion in paychecks, and accounts for $205 billion in tax revenues across the country. Historically, the auto industry has contributed between 3 - 3.5 percent to America’s total gross domestic product. No other single industry is linked to so much of U.S. manufacturing or generates so much retail business and employment. Automakers Offer Record-Breaking Choices in Fuel-efficient Vehicles Today The auto industry has invested billions of dollars on powertrain R&D and that investment is paying off – automakers are providing customers with record-breaking choice in fuel- efficient vehicles. -

Volkswagen Beetle History

Volkswagen Beetle History The very first Volkswagen type 1 ever produced. Volkswagen Beetle The Volkswagen Type 1 is an economy car produced by the German auto maker Volkswagen (VW) from 1938 until 2003. The car was originally known as Käfer, the German word for "beetle," from which the popular English nickname originates. It was not until August 1967 that the Volkswagen corporation itself began using the name Beetle in marketing materials in the US. 1933-1934 VW design drawings In Britain, VW never used the name Beetle officially. It had only been known as either the "Type I" or as the 1100, 1200, 1300, 1500, or 1600 which had been the names under which the vehicle was marketed in Europe; the numbers denoted the vehicle's approximate engine size in cubic centimetres. In 1998, many years after the original model had been dropped from the lineup in most of the world (production continued in Mexico until 2003), VW introduced the "New Beetle" (built on a Volkswagen Golf Mk4 platform) which bore a cosmetic resemblance to the original. 1934 VW Porsche-NSU Its peculiar styling, underpowered motor, rough ride, and high noise levels compared to modern vehicles might have made it a market failure. In its day, though, it was more comfortable and powerful than most European small cars, and ultimately the longest-running and most-produced automobile of a single design (a record that will not take long to be beaten by its younger "cousin" the Type-2 Bus or Kombi, which is still in production in Brazil, with the same basic characteristics of the first series).