Identity Politics of Football Supporters in the Era of Globalization and Commodification a Dutch Case Study at FC Twente

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CASE STUDY No. 4

UEFA COACHES CIRCLE EXTRANET CASE STUDY No. 4 CASE STUDY Number 11: An Integrated Youth Academy created by two neighbouring Dutch Premier League Clubs CASE STUDY NUMBER 11 An Integrated Youth Academy created by two neighbouring Dutch Premier League Clubs (A Brochure-only in Dutch - outlining this project is also available on the UEFA Coaches Extranet) 1. Background and Summary In Eastern Holland the area around the town of Enschede is somewhat remote from the rest of the Netherlands. Although only 5kms from the German border the two professional clubs that dominate the region are FC Twente ( TW) and FC Almelo Heracles (AH).These two clubs are 20 km from each other but the nearest other professional club-in the first division - is 50 kms away and the nearest current Dutch Premier League club is Vitesse Arnhem which is 90 kms from Enschede.In effect therefore the two clubs – FC Twente and FC Almelo ‘Hercules’ serve a regional population of 600,000 and are isolated from the rest of the Premier League clubs in Holland FC Twente have traditionally been a team in the highest Dutch League ,the ‘ Eredivisie ‘.They reached the final if the UEFA Cup in 1975 and after beating Juventus in the semi- finals, lost to German side Borussia Mönchengladbach in the finals Almelo Heracles (AH) has traditionally played more often in the league below the Eredivisie which in Holland is known as ‘Eerste Divisie’ AH were promoted to the Eredivisie in 2005. Historically TW have therefore been perceived as the bigger more successful club, spending longer in the top division. -

Messi Vs Martens

Messi vs Martens Researching the landscape of sport sponsoring; Do company sponsoring motives differ for sponsoring FC Twente men or FC Twente women? Student: Maud Roetgering Student number: 1990101 Advisor: Drs. Mark Tempelman Program: Communication Science Faculty of Behavioral, Management and Social Sciences Date: 26-06-2020 Abstract Description of objectives For FC Twente Men, it is quite “easy” to find sponsors. In contrast to FC Twente women, who find it difficult to attract sponsors. The central research question of this thesis is therefore: What are the motives of firm’s regarding sponsorship, and do firm’s motives differ in sponsoring men soccer or women soccer at FC Twente? Description of methods A (quantitative) Q-Sort methodology sorting task was conducted online, in combination with a follow-up interview (qualitative). Thirty respondents were purposively selected for the Q-sort. Five out of the original thirty respondents were randomly selected for the follow-up interview. Description of results Company sponsoring motives for FC Twente men and FC Twente women differ. Motives for FC Twente men were more opportunistic and economically oriented whereas motives to sponsor FC Twente women were more altruistic and emotionally oriented. Description of conclusions More specifically sponsoring motives for FC Twente men are more related to Market and Bond categories, whereas company sponsoring motives for FC Twente women are more related to the society category of the Sponsor Motive Matrix. Description of practical implications FC Twente should bear in mind the unique and different values and aspects FC Twente women has in comparison with FC Twente men. In addition, FC Twente women has a completely different audience then FC Twente men. -

Vriend Van Jong ADO Den Haag Vrouwen € 500 Exposure

ADO Den Haag Vrouwen KIES POSITIE | SPONSOR | MOGELIJKHEDEN KIES POSITIE! Bij de start van de Eredivisie Vrouwen in 2007 heeft ADO Den Haag heel nadrukkelijk positie gekozen voor het vrouwenvoetbal. Vóór de mogelijkheid om de snelst groeiende teamsport onder meisjes in Nederland een plek te geven onder de ADO-paraplu van helden als Aad Mansveld en Lex Schoenmaker, de club van strijd, passie en Haagse bluf. Maar dan wel met een “female touch”. 2 Hieruit zijn de ADO Powervrouwen geboren. Zij stralen Haagse onverzettelijkheid uit en zijn er in geslaagd zich een plaats te verwerven in de top van het Nederlands Vrouwenvoetbal. ADO Den Haag Vrouwen kan in die periode inmiddels terugkijken op een landskampioenschap en drie keer bekerwinst. Prestatief dus top! In het jaar waarin er 10 jaar professioneel vrouwenvoetbal wordt gespeeld in Den Haag zal het tegen ploegen als FC Twente, Ajax en PSV om het kampioenschap strijden. Het Kyocera Stadion is daarbij de plek voor alle thuiswedstrijden. 3 In 2014 koos ADO wederom positie door een team te starten dat moest gaan voorzien in de opleiding en ontwikkeling van jonge talenten. Als opleiding voor het eerste team, maar ook als plek om met gelijkgestemden de droom om professioneel voetbalster te worden te verwezenlijken. Inmiddels is Jong ADO Den Haag Vrouwen twee keer gepromoveerd (thans uitkomend in de Topklasse, het hoogste amateurniveau) en stromen er jaarlijks drie tot vier talenten door. En ook maatschappelijk kiezen de ADO Powervrouwen positie. Als geen ander begrijpen zij dat ze een inspiratiebron kunnen zijn voor meiden en vrouwen om uit te komen voor hun dromen en die ook te verwezenlijken. -

Record Clean Sheets

Hoe zit het nu met de clean sheets? Vrijdag behaalden Go Ahead Eagles en Jay Gorter tegen Roda JC Kerkrade hun 21e clean sheet van het seizoen, na 31 speelrondes (en met dus nog zeven wedstrijden te gaan). Een nieuw clubrecord was het al enige tijd, maar inmiddels is er ook sprake van een prestatie van nationale allure. Zowel club als keeper rukken nu op richting de algemene top vijf sinds de invoering van het betaalde voetbal in 1954. Wij maakten een inventarisatie om de huidige reeks in historisch perspectief te zetten. Een opmerking vooraf We moeten ons realiseren dat een clean sheet geen doel op zichzelf is. Wie elke wedstrijd met 0-0 gelijkspeelt, heeft weliswaar 38 clean sheets, maar wordt hooguit vijftiende in de competitie. Wie elke wedstrijd met 2-1 wint, heeft daarentegen geen enkel clean sheet, maar wordt wel kampioen. Het was daarom bijna paradoxaal dat er een zeker chagrijn heerste na de 5-1 winst tegen FC Dordrecht op 19 maart. Het was nota bene de grootste overwinning van het seizoen, maar dus geen clean sheet … Het negatieve sentiment was dus verre van rationeel, maar zo groot is kennelijk de magie van een record, ook als het gaat om een ‘onbedoeld’ record. Iets soortgelijks gold ook voor de serie van 22 ongeslagen officiële wedstrijden die Go Ahead Eagles vorig seizoen onder Jack de Gier neerzette. Ook hier was geen sprake van een ‘bewuste’ serie, maar meer van een ‘bijvangst’. Wie elke wedstrijd met 0-0 afsluit en dus 38 keer ongeslagen blijft, wordt immers opnieuw hooguit vijftiende op de ranglijst. -

Conceptprogramma Eredivisie

CONCEPTPROGRAMMA EREDIVISIE SEIZOEN 2020/’21 1 Ronde Datum Thuis Uit Tijd UCL Q2 din. 25 / woe. 26 aug 2020 AZ Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Jong Wit Rusland Jong Oranje Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Nederland Polen 20:45 Int vrijdag 4 september 2020 Nederland O19 Zwitserland O19 Int maandag 7 september 2020 Nederland Italië 20:45 Int dinsdag 8 september 2020 Jong Oranje Jong Noorwegen Int dinsdag 8 september 2020 Tsjechië O19 Nederland O19 1 zaterdag 12 september 2020 FC Utrecht AZ 16:30 1 zaterdag 12 september 2020 sc Heerenveen Willem II 18:45 1 zaterdag 12 september 2020 PEC Zwolle Feyenoord 20:00 1 zaterdag 12 september 2020 FC Twente Fortuna Sittard 21:00 1 zondag 13 september 2020 FC Emmen VVV-Venlo 12:15 1 zondag 13 september 2020 Heracles ADO Den Haag 14:30 1 zondag 13 september 2020 Sparta Rotterdam Ajax 14:30 1 zondag 13 september 2020 FC Groningen PSV 16:45 1 zondag 13 september 2020 RKC Waalwijk Vitesse 16:45 UCL Q3 din. 15 / woe. 16 september 2020 AZ (?) UELQ2 donderdag 17 september 2020 Willem II 2 vrijdag 18 september 2020 VVV-Venlo FC Utrecht 20:00 2 zaterdag 19 september 2020 AZ PEC Zwolle 16:30 2 zaterdag 19 september 2020 Vitesse Sparta Rotterdam 18:45 2 zaterdag 19 september 2020 Ajax RKC Waalwijk 20:00 2 zaterdag 19 september 2020 Fortuna Sittard sc Heerenveen 21:00 2 zondag 20 september 2020 ADO Den Haag FC Groningen 12:15 2 zondag 20 september 2020 Feyenoord FC Twente 14:30 2 Ronde Datum Thuis Uit Tijd 2 zondag 20 september 2020 Willem II Heracles 14:30 * 2 zondag 20 september 2020 PSV FC Emmen 16:45 * Eventueel op verzoek naar 20.00 uur irt UEL UCL PO din. -

Giovanni Van Bronckhorst D-Jeugd Edwin Krohne

DeVoetba lTrainer 30 e JAARGANG | JUNI 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 194 Trainerscongres 2013 Mini-special Training, discussie en Cursus Coach Betaald Voetbal Awards Remy Reijnierse Leercoach 25 jaar na EK 1988 Succesfactoren KNVB-katern Iedereen heeft Voetbaltalent GEEN TALENT MAG VERLOREN GAAN nummer nummer 7 Danny Volkers Relatiegerichte trainer Peter Wesselink Bewust handelen Coachen van emoties Wat kun je doen als trainer? Spelregels Kennis voorkomt frustratie Goede initiatieven Clubs maken er werk van Robur et Velocitas verhoogt participatie in club Column Geen excuus Thema-nummer Sportiviteit en respect trainers.voetbal.nl De Voetbaltrainer 194 2013 55_coverknvb-katern.indd 55 21-05-13 16:05 De JeugdVoetbalTrainer De JeugdVoetba lTrainer 3e JAARGANG | JUNI 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 17 Normaal gedrag René Koster Zelfregulatie Onderzoek Talentontwikkeling Rijpen van hersenen Vrijheid geven Balanceren Thema: Aanvallen op helft tegenstander A-jeugd John Dooijewaard B-jeugd Paul Bremer C-jeugd René Kepser Giovanni van Bronckhorst D-jeugd Edwin Krohne 31_JVT-cover.indd 31 22-05-13 08:20 ‘Ideaal leerjaar’ 01_cover.indd 1 22-05-13 08:23 Superactie van DeVoetba lTrainer Word ook abonnee & profi teer mee! DeVoetba lTrainer 30 e JAARGANG | APRIL 2013 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 193 Voetbaltrainer Omgang met media De sliding Vooroordelen Aad de Mos Zoekt creatieve trainers Presteren onder druk Mentaal trainbaar KNVB-katern Iedereen heeft Voetbaltalent GEEN TALENT MAG VERLOREN GAAN nummer nummer -

Riel En Willem II

TOEKOMST MET HISTORIE Promotie VV Riel 1 seizoen 2015 2016 Riel, 27 augustus 2016 Eindelijk promotie van het eerste elftal van V.V. Riel van de 5e klasse naar de 4e klasse KNVB., onder leiding van de jonge trainer, Mathieu van der Steen. Dit heeft 40 jaar mogen duren. Vorige promotie was in het seizoen 1975 1976 waarin een uniek resultaat werd behaald, aangezien zowel Riel 1 als Riel 2 kampioen werden, onder leiding van trainer Gabor Keresztes. Riel 1 promoveerde in dat seizoen naar de 4e klasse KNVB. Het tweede elftal slaagde niet in promotie aangezien de beslissingswedstrijd verloren werd. Riel 1 is in de laatste 50 jaar nu drie maal naar de 4e klasse gepromoveerd, in 1968 1969 door ook de titel te winnen en te promoveren naar de 4e klasse, onder leiding van trainer Christ Feijt. Daarnaast was er nog een promotie van de tweede klasse Brabantse Bond naar de eerste klasse Brabantse Bond in het seizoen 1987 1988, onder leiding van Charles Schutter, na een paar jaar in de tweede klasse te hebben vertoefd. Eveneens wist Riel 2 in het seizoen 2009 2010 nog kampioen te worden en te promoveren.En nu dus na 40 jaar, Riel 1 gepromoveerd via de nacompetitie , tegen ja, de amateurs van Willem II. Resumerend is dus in 50 jaar tijd Riel 1 viermaal gepromoveerd en Riel 2 tweemaal kampioen geworden, waarvan eenmaal gepromoveerd. Allengs kwam het idee om de geschiedenis van VV Riel samen te brengen met Willem II, gezien het feit dat diverse Willem II coryfeeën in het verleden trainer zijn geweest van VV Riel. -

Clubs Without Resilience Summary of the NBA Open Letter for Professional Football Organisations

Clubs without resilience Summary of the NBA open letter for professional football organisations May 2019 Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants The NBA’s membership comprises a broad, diverse occupational group of over 21,000 professionals working in public accountancy practice, at government agencies, as internal accountants or in organisational manage- ment. Integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behaviour are fundamental principles for every accountant. The NBA assists accountants to fulfil their crucial role in society, now and in the future. Royal Netherlands Institute of Chartered Accountants 2 Introduction Football and professional football organisations (hereinafter: clubs) are always in the public eye. Even though the Professional Football sector’s share of gross domestic product only amounts to half a percent, it remains at the forefront of society from a social perspective. The Netherlands has a relatively large league for men’s professio- nal football. 34 clubs - and a total of 38 teams - take part in the Eredivisie and the Eerste Divisie (division one and division two). From a business economics point of view, the sector is diverse and features clubs ranging from listed companies to typical SME’s. Clubs are financially vulnerable organisations, partly because they are under pressure to achieve sporting success. For several years, many clubs have been showing negative operating results before transfer revenues are taken into account, with such revenues fluctuating each year. This means net results can vary greatly, leading to very little or even negative equity capital. In many cases, clubs have zero financial resilience. At the end of the 2017-18 season, this was the case for a quarter of all Eredivisie clubs and two thirds of all clubs in the Eerste Divisie. -

UEFA Competitions Cases: July

INTEGRITY AND REGULATORY DIVISION Case Law Control, Ethics and Disciplinary Body Appeals Body CFCB Adjucatory Chamber July – December 2018 Case Law - July to December 2018 CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Control, Ethics and Disciplinary Body.................................................................................................................................. 7 Decision of 27 July 2018 .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 PFC CSKA- Sofia ....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 (Improper conduct of official; Direct red card-assault) ............................................................................................. 8 Decision of 23 August 2018 ................................................................................................................................................. 13 FK Radnicki Niš ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 (Racist behavior; Setting off fireworks) ........................................................................................................................ -

Concept Divisie-Indeling Onder 18 Seizoen 2020-2021

Concept divisie-indeling Onder 18 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 18 Divisie 1 Divisie 1 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Ajax AFC O18-1 West I AZ O18-1 West I FC Utrecht Academie O18-1 West I Feyenoord Rotterdam N.V. O18-1 West II PEC Zwolle O18-1 Oost PSV O18-1 Zuid I Sparta Rotterdam O18-1 West II Stichting sc Heerenveen O18-1 Noord Onder 18 Divisie 2 Divisie 2 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal ADO Den Haag, HFC O18-1 West II AFC O18-1 West I FC Groningen BV O18-1 Noord FC Twente / Heracles Academie O18-1 Oost FC Volendam O18-1 West I N.E.C. (voetbalacademie) O18-1 Oost NAC O18-1 Zuid I Vitesse-Arnhem O18-1 Oost Concept divisie-indeling Onder 18 seizoen 2020-2021 Onder 18 Divisie 3 Divisie 3 (1 poule van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Almere City FC O18-1 West I Alphense Boys O18-1 West Ii De Graafschap O18-1 Oost FC Dordrecht O18-1 Zuid I Koninklijke HFC O18-1 West I SBV Excelsior O18-1 West II VVV-Venlo/Helmond Sport O18-1 Zuid II Willem II Tilburg BV O18-1 Zuid I Onder 18 Divisie 4 Divisie 4 (2 poules van 8) Organisatie: KNVB Betaald Voetbal Alexandria'66 O18-1 West II Hercules O18-1 West I Argon O18-1 West I Hollandia O18-1 West I DEM (RKVV) O18-1 West I MVV O18-1 Zuid II DWS afc O18-1 West I RJO Brabant United O18-1 Zuid I Excelsior M. -

Start List Netherlands - Ghana # 10 08 AUG 2018 16:30 Vannes / Stade De La Rabine / FRA

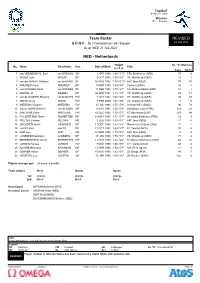

FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup France 2018 Group A Start list Netherlands - Ghana # 10 08 AUG 2018 16:30 Vannes / Stade de la Rabine / FRA Netherlands (NED) Shirt: orange Shorts: orange Socks: orange Competition statistics # Name ST Pos DOB Club H MP Min GF GA AS Y 2Y R 1 Lize KOP (C) GK 17/03/98 Ajax (NED) 175 1 90 1 2 Jasmijn DUPPEN DF 26/08/98 VV Alkmaar (NED) 174 1 90 3 Caitlin DIJKSTRA DF 30/01/99 Ajax (NED) 170 1 90 5 Aniek NOUWEN DF 09/03/99 PSV (NED) 174 1 90 6 Eva VAN DEURSEN MF 21/01/99 Arizona State (USA) 165 1 90 1 11 Ashleigh WEERDEN FW 07/06/99 FC Twente (NED) 156 1 68 12 Danique YPEMA DF 20/11/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 176 1 90 14 Victoria PELOVA MF 03/06/99 ADO Den Haag (NED) 163 1 90 1 15 Lisa DOORN DF 08/12/00 Ajax (NED) 183 1 90 17 Naomi PATTIWAEL FW 21/07/98 PSV (NED) 164 1 89 19 Fenna KALMA FW 21/11/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 173 1 83 1 1 Substitutes 4 Sabine KUILENBURG DF 12/04/99 ADO Den Haag (NED) 177 7 Bente JANSEN FW 28/08/99 FC Twente (NED) 179 1 22 8 Quinty SABAJO FW 01/08/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 164 1 1 9 Joelle SMITS FW 07/02/00 FC Twente (NED) 169 1 7 10 Nathalie VAN DEN HEUVEL MF 17/06/98 sc Heerenveen (NED) 168 13 Noah WATERHAM DF 09/04/99 sc Heerenveen (NED) 172 16 Daphne VAN DOMSELAAR GK 06/03/00 FC Twente (NED) 176 18 Nurija VAN SCHOONHOVEN MF 08/02/98 PSV (NED) 174 20 Kim VAN VELZEN MF 19/01/98 sc Heerenveen (NED) 168 21 Jacintha WEIMAR GK 11/06/98 Bayern München (GER) 179 Coach Michel KREEK (NED) Ghana (GHA) Shirt: white Shorts: white Socks: white Competition statistics # Name ST Pos DOB Club H MP Min GF GA AS Y 2Y R 16 Martha ANNAN GK 02/11/99 Sea Lions Ladies Clu. -

REVISED Team Roster

Football サッカー / Football Women 女子 / Femmes Team Roster REVISED 登録選手一覧 / Composition de l’équipe 22 JUL 0:48 As of WED 21 JUL 2021 NED - Netherlands Height Int. "A" Matches No. Name Shirt Name Pos. Date of Birth Club m / ft in Caps Goals 1 van VEENENDAAL Sari van VEENENDAAL GK 3 APR 1990 1.80 / 5'11" PSV Eindhoven (NED) 74 0 2 WILMS Lynn WILMS DF 3 OCT 2000 1.76 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 12 1 3 van der GRAGT Stefanie van der GRAGT DF 16 AUG 1992 1.78 / 5'10" AFC Ajax (NED) 75 10 4 NOUWEN Aniek NOUWEN DF 9 MAR 1999 1.74 / 5'9" Chelsea (ENG) 16 1 5 van DONGEN Merel van DONGEN DF 11 FEB 1993 1.70 / 5'7" CA Atlético Madrid (ESP) 51 1 6 ROORD Jill ROORD MF 22 APR 1997 1.75 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 64 11 7 van de SANDEN Shanice van de SANDEN FW 2 OCT 1992 1.68 / 5'6" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 85 19 8 SMITS Joelle SMITS FW 7 FEB 2000 1.68 / 5'6" VfL Wolfsburg (GER) 4 0 9 MIEDEMA Vivianne MIEDEMA FW 15 JUL 1996 1.75 / 5'9" Arsenal WFC (ENG) 96 73 10 van de DONK Danielle van de DONK MF 5 AUG 1991 1.60 / 5'3" Olympique Lyon (FRA) 114 28 11 MARTENS Lieke MARTENS FW 16 DEC 1992 1.70 / 5'7" FC Barcelona (ESP) 123 49 12 FOLKERTSMA Sisca FOLKERTSMA DF 21 MAY 1997 1.71 / 5'7" Girondins Bordeaux (FRA) 12 0 13 PELOVA Victoria PELOVA MF 3 JUN 1999 1.63 / 5'4" AFC Ajax (NED) 11 0 14 GROENEN Jackie GROENEN MF 17 DEC 1994 1.65 / 5'5" Manchester United (ENG) 71 7 15 van ES Kika van ES DF 11 OCT 1991 1.69 / 5'7" FC Twente (NED) 70 0 16 KOP Lize KOP GK 17 MAR 1998 1.73 / 5'8" AFC Ajax (NED) 6 0 17 JANSSEN Dominique JANSSEN DF 17 JAN 1995 1.75 / 5'9" VfL Wolfsburg