T16S R18E S8 Resolution NEPA Register Number DOI‐BLM‐ORWA‐P000‐2017‐0046‐EA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timing of In-Water Work to Protect Fish and Wildlife Resources

OREGON GUIDELINES FOR TIMING OF IN-WATER WORK TO PROTECT FISH AND WILDLIFE RESOURCES June, 2008 Purpose of Guidelines - The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, (ODFW), “The guidelines are to assist under its authority to manage Oregon’s fish and wildlife resources has updated the following guidelines for timing of in-water work. The guidelines are to assist the the public in minimizing public in minimizing potential impacts to important fish, wildlife and habitat potential impacts...”. resources. Developing the Guidelines - The guidelines are based on ODFW district fish “The guidelines are based biologists’ recommendations. Primary considerations were given to important fish species including anadromous and other game fish and threatened, endangered, or on ODFW district fish sensitive species (coded list of species included in the guidelines). Time periods were biologists’ established to avoid the vulnerable life stages of these fish including migration, recommendations”. spawning and rearing. The preferred work period applies to the listed streams, unlisted upstream tributaries, and associated reservoirs and lakes. Using the Guidelines - These guidelines provide the public a way of planning in-water “These guidelines provide work during periods of time that would have the least impact on important fish, wildlife, and habitat resources. ODFW will use the guidelines as a basis for the public a way of planning commenting on planning and regulatory processes. There are some circumstances where in-water work during it may be appropriate to perform in-water work outside of the preferred work period periods of time that would indicated in the guidelines. ODFW, on a project by project basis, may consider variations in climate, location, and category of work that would allow more specific have the least impact on in-water work timing recommendations. -

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the Re-Opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the re-opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside.... Be Safe! 2 LAWRENCE A. CHITWOOD Go To Special Places 3 EXHIBIT HALL Lava Lands Visitor Center 4-5 DEDICATED MAY 30, 2009 Experience Today 6 For a Better Tomorrow 7 The Exhibit Hall at Lava Lands Visitor Center is dedicated in memory of Explore Newberry Volcano 8-9 Larry Chitwood with deep gratitude for his significant contributions enlightening many students of the landscape now and in the future. Forest Restoration 10 Discover the Natural World 11-13 Lawrence A. Chitwood Discovery in the Kids Corner 14 (August 4, 1942 - January 4, 2008) Take the Road Less Traveled 15 Larry was a geologist for the Deschutes National Forest from 1972 until his Get High on Nature 16 retirement in June 2007. Larry was deeply involved in the creation of Newberry National Volcanic Monument and with the exhibits dedicated in 2009 at Lava Lands What's Your Interest? Visitor Center. He was well known throughout the The Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests are a recre- geologic and scientific communities for his enthusiastic support for those wishing ation haven. There are 2.5 million acres of forest including to learn more about Central Oregon. seven wilderness areas comprising 200,000 acres, six rivers, Larry was a gifted storyteller and an ever- 157 lakes and reservoirs, approximately 1,600 miles of trails, flowing source of knowledge. Lava Lands Visitor Center and the unique landscape of Newberry National Volcanic Monument. Explore snow- capped mountains or splash through whitewater rapids; there is something for everyone. -

OREGON FURBEARER TRAPPING and HUNTING REGULATIONS

OREGON FURBEARER TRAPPING and HUNTING REGULATIONS July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2022 Please Note: Major changes are underlined throughout this synopsis. License Requirements Trapper Education Requirement By action of the 1985 Oregon Legislature, all trappers born after June 30, Juveniles younger than 12 years of age are not required to purchase a 1968, and all first-time Oregon trappers of any age are required to license, except to hunt or trap bobcat and river otter. However, they must complete an approved trapper education course. register to receive a brand number through the Salem ODFW office. To trap bobcat or river otter, juveniles must complete the trapper education The study guide may be completed at home. Testing will take place at course. Juveniles 17 and younger must have completed hunter education Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) offices throughout the to obtain a furtaker’s license. state. A furtaker’s license will be issued by the Salem ODFW Headquarters office after the test has been successfully completed and Landowners must obtain either a furtaker’s license, a hunting license for mailed to Salem headquarters, and the license application with payment furbearers, or a free license to take furbearers on land they own and on has been received. Course materials are available by writing or which they reside. To receive the free license and brand number, the telephoning Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, I&E Division, 4034 landowner must obtain from the Salem ODFW Headquarters office, a Fairview Industrial Drive SE, Salem, OR 97302, (800) 720-6339 x76002. receipt of registration for the location of such land prior to hunting or trapping furbearing mammals on that land. -

2021-06-5C.Pdf

Oregon Parks and Recreation Commission June 23, 2021 Agenda Item: 5c Information Topic: Prineville Resort Property – Prineville Reservoir Presented by: J.R. Collier, Mountain Region Manager OPRD manages the complex of parks and properties around Prineville Reservoir under an agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation (BoR) who is the property owner. This agreement was last renewed in 2011 for a period of twenty-five years. OPRD manages the property for recreation and the BoR supports that mission by providing support in the way of maintenance and operations funding that in the current biennium accounts for roughly 16% of the unit’s 2 million dollar operating budget. In addition, the BoR can provide maintenance assistance grants as funding allows to help with capital improvement projects on the property. In 2019, the BoR approached OPRD and asked us to consider assuming management of additional land around the reservoir that had been in use as a private concessionaire operating a small campground, lodging and marina area known as the Prineville Resort. The operator of the Resort terminated his agreement with BoR and the property was vacated. BoR let us know that they would not be seeking to renew an agreement with private concessionaires, but they would like to add this property to our existing agreement with them. Staff recommended taking on this property as it gives OPRD oversight of the entire reservoir area with the exception of one small collection of homes. An amendment to the master lease was executed in June of 2020, adding the Prineville Resort property under OPRD’s management. -

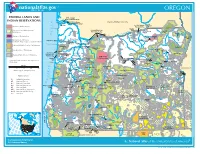

OREGON Where We Are

nationalatlas.gov TM OREGON Where We Are FEDERAL LANDS AND Lewis and Clark INDIAN RESERVATIONS National Wildlife Refuge Astoria Julia Butler Hansen WASHINGTON N National Wildlife Refuge Lake Camp Riley Umatilla Chemical A Wallula Bureau of Indian Affairs Depot (Closed) Seaside E Umatilla R Bureau of Land Management / Columbia River Gorge NWR St Helens National Scenic Area Cold Springs Umatilla Wilderness C bia NWR NF lum Wallowa O NF Bureau of Reclamation Co McKay Umatilla Hells Canyon Reservoir Boardman IR NRA Department of Defense Cape Meares NWR Portland The Dalles Naval McKay Creek (includes Army Corps of Engineers lakes) Tillamook Bombing Range NWR Henry Hagg Gresham Enterprise Reservoir Cape Lookout Tualatin River NWR Fish and Wildlife Service / Wilderness J La Grande Grand Ronde Eagle Creek o Wallowa NF IR National Fish Hatchery Mount Hood h Condon n Forest Service / Wilderness McMinnville NF Whitman NF Thief Valley Siuslaw D Reservoir Cascade Head a Umatilla NF NF Baskett Slough Keizer Whitman NF National Scenic y Umatilla National Park Service / Wilderness Research Area NWR Salem Warm Springs R NF Siletz Bay Siletz Ankeny NWR Detroit Indian Reservation John Day Fossil Beds Baker City NWR Lake Vinegar Hill-Indian Rock Some small sites are not shown, especially in IR Camp Adair National Monument Scenic Area urban areas. Newport Albany Madras Phillips Reservoir Willamette Malheur WhitmanNF Corvallis NF NF MILES Crooked River R C Foster Lake Green Peter Lake iver Unity 0 20 40 60 80 NG John Day Reservoir IDAHO I William L Finley -

Brothers Grazing Management Program Environmental Impact Statement DRAFT

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management District Office PO. Box 550 Prineville, Oregon of the OF LAND MANAGEMENT Prineville District Office P.O. Box 550 Prineville, Oregon 97754 Enclosed for your review and comment is the Brothers Grazing Management Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The statement analyzes the-impacts which would result from the proposed livestock management program and four alternatives. The purpose of the statement is to disclose the probable environmental impacts for consideration along with economic and technical information in the decisionmaking process. Comments concerning the adequacy of this statement will be considered in the preparation of the final environmental impact statement. The comment period will end June Informal discussion sessions intended to assist you in reviewing and commenting on the draft EIS will be held at 7:00 p.m., May 251982, at St. Joseph’s Parish Hall, 150 East First St., Prineville, Oregon and at 7:00 p.m., May 26, 1982, at the Bend Riverhouse Motor Inn, 3075 North Highway 97, Bend, Oregon. Bureau of Land Management personnel will be available at both sessions to answer questions regarding the draft EIS analysis. The draft EIS may be incorporated into the final EIS by reference only. The final EIS then would consist of public comments and responses and any needed changes of the draft. Therefore, please retain this Draft EIS for use with the final. Comments received after the close of the comment period will be considered in the decision process, even though they may be too late be specifically addressed in the final environmental impact statement. -

Prineville Reservoir

Reserve early! Reserve campsites and cabins two days to nine Need to cancel your reservation? Follow this guideline: Park Information: 63400-8841 (2/12) Prineville months in advance by phone–Reservations Northwest (1-800-452-5687)– If your reservation is for today or tomorrow, call 541-447-4363. 1-800-551-6949 Reservoir or online through www.oregonstateparks.org. Otherwise, call Reservations Northwest at 1-800-452-5687. www.oregonstateparks.org Discovery Season Popular finds include agates with dendrites, white plume Prineville Reservoir State Park has two campgrounds and two agates, various colored moss agates, green jasper, jasper day-use areas with boat ramps on the shore of a high desert From October 1-April 30, camping in an Oregon state park costs less. At Prineville Reservoir’s main campground, you interlaced with agate, Ochoco chalcedony, thunder eggs canyon lake near the center of the state. It is an ideal destina- and petrified wood. tion for year-round fishing and wildlife viewing, and for sum- save $4 per night off summer rates on full hookup, electrical CAMPGROUND mertime stargazing. and tent sites. Want to see a really big rock? Explore Steins Pillar, a geological landmark on Mill Creek Road, 15 miles northeast of Prineville. Main Campground Enjoy Cabin Comforts (Full hookup sites open year-round) Enjoy a view of the reservoir from three of the five deluxe cabins or camp with your pet in cabin number 5. Maximum 22 full hookup sites (sewer, electricity, water) • 2 pets (cats and/or dogs only; donations accepted. All five To Prineville 22 electrical sites with water of the cabins have bathrooms with showers, sleeping for 16 miles • 26 six on beds with vinyl covered mattresses, heating and air- Jasper Point Campground 23 tent sites with water nearby • conditioning, a microwave, refrigerator, and outdoor gas and Day-use Area • 5 deluxe log cabins (Cabin 5 is pet friendly) barbecue. -

May 2012 Contents RANDOM CAST

C O G N N S I E T R A V C I U N D G E • • entral regon lyfisher R G ESTORIN C O F Vol. 35, Number 5, May 2012 CONTENTS RANDOM CAST General meeting On March 31, 125 people sat down for dinner at the Annual COF Banquet and Auc- 2 Tenkara: the tradition, art tion. The evening was enjoyed by all, and the net proceeds were $7,600. Thank you to all and techniques who participated. Special thanks to the banquet committee: Howard Olson, Debbie Norton, Outings Craig Dennis and Gary Myer and volunteers Bob Griffin, Tim and Renee Schindele, Char- 2 Davis Lake (bass) lotte Oakes, Kathleen and Bruce Schroeder, Dan Pebbles, Karen Kreft, Todd & Corol Ann 3 Lakes of Central Washington Cary and others who made things run smoothly. Two important awards were presented that 3 Antelope Flat Reservoir evening. Dave Dunahay was awarded an Honorary Life member award for his many years 4 Float the lower Deschutes of outstanding leadership and support to the COF mission. This award has been presented 4 Crooked River for beginners thirteen times in the history of COF. Yancy Lind received the 2011 Fly Fisher of the Year 5 Prineville Reservoir crappie award in recognition of his work as leader for the outings program, a fly-fishing teacher and 5 Chewaucan River his extensive work in water conservation efforts for fish. Please support the businesses that Education support COF, especially our major sponsors — the fly shops and guide services. In addition 5 Fly-casting basics to donating the items listed below, these businesses support COF through fly-fishing educa- -

Crook County Community Wildfire Protection Plan August 2014

Crook County Community Wildfire Protection Plan August 2014 1 As required by the Healthy Forest Restoration Act, the undersigned representatives of Crook County, Crook County Fire Chief, and Oregon Department of Forestry acknowledge that they have reviewed and approve the contents of this plan. Crook County Commission Chair ____________________________________________ ______________ Commissioner Fahlgren Date Crook County Fire and Rescue ___________________________________________ _____________ Matt Smith Date Oregon Department of Forestry ________________________________________ _____________ George Ponte Date 2 This Community Wildfire Protection Plan represents the efforts and cooperation of a number of organizations and agencies working together to improve preparedness for wildfire events while reducing risk factors. 2013-14 Steering Committee Guy Chamness Bureau of Land Management Pete Ridenour Central Oregon Fire Management Service/BLM Bryan Scholz Central Oregon Fire Management Service John Jackson Consultant Ken Fahlgren Crook County Commissioner Casey Kump Crook County Fire and Rescue Michael Ryan Crook County Sheriff Bob and Jerri Bronson Dry Creek Airpark Residents Gordon Foster Sr. Oregon Department of Forestry Gordon Foster Jr. Oregon Department of Forestry Kevin Benton Oregon Department of Forestry Map Production Steve Dougill Crook County GIS Department Levi Roberts Crook County GIS Department This plan is available online at: www.coic2.org/crook-county-cwpp Or contact the following agencies: Crook County Administration Colleen Ferguson 300 NE 3rd Street 541-447-6555 Central Oregon Intergovernmental Council Tami Geiger, Program Coordinator 334 NE Hawthorne Ave., Bend OR [email protected] | 541.548-9527 June 2014 (v.2) Author: Tami Geiger, Central Oregon Intergovernmental Council June 2005 (v.1) Author: John Jackson, Consultant, Singletree Enterprises, LLC 3 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... -

Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

Attachment 2 OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE ARCHIVES DIVISION BEV CLARNO STEPHANIE CLARK SECRETARY OF STATE INTERIM DIRECTOR A. RICHARD VIAL 800 SUMMER STREET NE DEPUTY SECRETARY OF STATE SALEM, OR 97310 503-373-0701 NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING INCLUDING STATEMENT OF NEED & FISCAL IMPACT FILED 07/19/2019 2:56 PM CHAPTER 635 ARCHIVES DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE SECRETARY OF STATE FILING CAPTION: 2020 Big Game Controlled Hunt Tag Numbers, Season Dates and Regulations LAST DAY AND TIME TO OFFER COMMENT TO AGENCY: 09/13/2019 5:00 PM The Agency requests public comment on whether other options should be considered for achieving the rule's substantive goals while reducing negative economic impact of the rule on business. CONTACT: Roxann Borisch 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE Filed By: 503-947-6314 Salem,OR 97302 Roxann Borisch [email protected] Rules Coordinator HEARING(S) Auxilary aids for persons with disabilities are available upon advance request. Notify the contact listed above. DATE: 09/13/2019 TIME: 8:00 AM - 5:00 PM OFFICER: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Commissioners ADDRESS: The Event Center 29392 Ellensburg Ave Gold Beach, OR 97444 NEED FOR THE RULE(S): This action is necessary to set 2020 hunting season regulations and controlled hunt tag numbers for game mammals. DOCUMENTS RELIED UPON, AND WHERE THEY ARE AVAILABLE: A copy of the rules and the other documents relied upon for this rulemaking are available from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Division, 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE, Salem, Oregon 97302-1142, between the hours of 8:00 a.m. -

Three Sisters Irrigation District Obtains Its Water from Whychus Creek, Which Flows Into the Deschutes River About 39 Miles Downstream from Bend

DESCHUTES BASIN HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN STUDY REPORT Study 1 – Phase 1: Comparison of Natural and Current Stream Flows in the Deschutes River Basin Prepared for: Deschutes Basin Board of Control, and City of Prineville, Oregon Prepared by: Newton Consultants, Inc. August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Overview ............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Definitions ................................................................................................................ 3 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................... 3 4.0 Results ..................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 Whychus Creek .................................................................................................... 6 4.1.1 Analysis Points and Reference Years .......................................................... 6 4.1.2 Effects of Water Diversion on Instream Flow ............................................ 8 4.2 Crooked River ..................................................................................................... 16 4.2.1 Ochoco Irrigation District .......................................................................... -

Crook County Spotlight

An Oregon 2020 Publication 5/15/2017 CROOK COUNTY SPOTLIGHT What is a Blitz? Birders from around the state gather in a single Friday, June 16 to county to survey as many birds in as many places as possible in just Sunday, June 18 in one weekend. Multiple stationary counts within Oregon2020 Hotspot Blitz Squares are encouraged (click here for our protocol). Participation in Dates Prineville, OR Blitzes is free! To register, visit: http://oregon2020.com/crook/ Overview of Crook County Located in the heart of Oregon, Crook County is known for its agriculture and forest products, as well as its fantastic recreational areas. Fishing is very popular all year-round. Below the Bowman Dam, Fast Facts the Crooked River is one of the most • All-Time Bird Species productive trout streams in Oregon. Visit Total: 280 the Ochoco National Forest and explore • Breeding Season Bird geological oddities, hunt for gemstones, Above: Just east of Bend and Redmond, and experience dense pine forests with Species Total: 249 • Total number of eBird Crook County contains the Ochoco nearly 95,000 acres of old growth. Mountains and the city of Prineville. checklists: 3,806 The Feisty and Vocal Gray Flycatcher The Gray Flycatcher is commonly found in semi-arid woodlands, sage brush, shrub-steppe, pinyon-juniper, and yellow pine forests. This flycatcher actively defends its territories and forages for insects from srubs or branches low in trees. It maintains its territories using vocalizations and displays such as tail-pumping, crest-raising, Photo: Francesco Veronesi and elaborate fighting. Gray flycatchers defend territories Crook County Species against both Gray and Dusky Highlights: flycatchers, because they • Mountain Bluebird cannot distinguish between • Black-billed Magpie these intruders by appearance • Brewer’s Sparrow alone.