Review Essay: Stabilizing Nuclear Southern Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Borders Irrelevant in Kashmir Will Be Swift and That India-Pakistan Relations Will Rapidly Improve Could Lead to Frustrations

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T P. R. Chari and Hasan Askari Rizvi This report analyzes the possibilities and practicalities of managing the Kashmir conflict by “making borders irrelevant”—softening the Line of Control to allow the easy movement of people, goods, and services across it. The report draws on the results of a survey of stakeholders and Making Borders public opinion on both sides of the Line of Control. The results of that survey, together with an initial draft of this report, were shown to a group of opinion makers in both countries (former bureaucrats and diplomats, members of the irrelevant in Kashmir armed forces, academics, and members of the media), whose comments were valuable in refining the report’s conclusions. P. R. Chari is a research professor at the Institute Summary for Peace and Conflict Studies in New Delhi and a former member of the Indian Administrative Service. Hasan Askari • Neither India nor Pakistan has been able to impose its preferred solution on the Rizvi is an independent political and defense consultant long-standing Kashmir conflict, and both sides have gradually shown more flexibility in Pakistan and is currently a visiting professor with the in their traditional positions on Kashmir, without officially abandoning them. This South Asia Program of the School of Advanced International development has encouraged the consideration of new, creative approaches to the Studies, Johns Hopkins University. management of the conflict. This report was commissioned by the Center • The approach holding the most promise is a pragmatic one that would “make for Conflict Mediation and Resolution at the United States borders irrelevant”—softening borders to allow movement of people, goods, and Institute of Peace. -

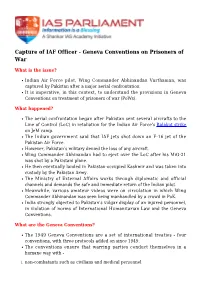

Capture of IAF Officer - Geneva Conventions on Prisoners of War

Capture of IAF Officer - Geneva Conventions on Prisoners of War What is the issue? Indian Air Force pilot, Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman, was captured by Pakistan after a major aerial confrontation. It is imperative, in this context, to understand the provisions in Geneva Conventions on treatment of prisoners of war (PoWs). What happened? The aerial confrontation began after Pakistan sent severalaircrafts to the Line of Control (LoC) in retaliation for the Indian Air Force's Balakot strike on JeM camp. The Indian government said that IAF jets shot down an F-16 jet of the Pakistan Air Force. However, Pakistan’s military denied the loss of any aircraft. Wing Commander Abhinandan had to eject over the LoC after his MiG-21 was shot by a Pakistani plane. He then eventually landed in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and was taken into custody by the Pakistan Army. The Ministry of External Affairs works through diplomatic and official channels and demands the safe and immediate return of the Indian pilot. Meanwhile, various amateur videos were on circulation in which Wing Commander Abhinandan was seen being manhandled by a crowd in PoK. India strongly objected to Pakistan’s vulgar display of an injured personnel, in violation of norms of International Humanitarian Law and the Geneva Conventions. What are the Geneva Conventions? The 1949 Geneva Conventions are a set of international treaties - four conventions, with three protocols added on since 1949. The conventions ensure that warring parties conduct themselves in a humane way with - i. non-combatants such as civilians and medical personnel ii. combatants no longer actively engaged in fighting, such as prisoners of war, and wounded or sick soldiers PoWs are usually members of the armed forces of one of the parties to a conflict who fall into the hands of the adverse party. -

Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman

C M C M Y K Y K gj xzg.kh dh ilan Ph. 2547421 JMC IS:2347 Daily Regd. No.:- JK-355/19-21 BPL M/s Parshotam Lal WROUGHT ALUMINIUM CM/L-3107639 PRESSURE Majahan & Co. COOKER Regd. No. 988704 Lakhdata Bazar, NAV JAMMU Jammu BPLR Deals in :- Cosmetics, Horiery, Bags, Belts, Misc Items. STAR APPLIANCES Voice of People WHOLE SALE SHOP Delhi Vol No. 18 No. 53 Jammu, Saturday March 02, 2019 Re. 1.00 Page-12 e-paper: epaper.navjammu.com R.N.I. Registration No. JKENG/2003/11218 News in Brief Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman comes home: Rain, snow likely Three security personnel, civilian killed in across JK on March 2-4 What forced Pakistan to return captured IAF pilot encounter with militants in Kupwara NJNS Srinagar, Mar 01 : NJNS Sonum Lotus, the Di- Srinagar, Mar 01 : rector of state's mete- Attari/New Delhi, Mar 01 : As the entire Three security personnel orological depart, on and a civilian were killed Friday said that mod- country on Friday cel- ebrated the homecoming in an encounter in erate rain or snow is Jammu and Kashmir's likely to be witnessed of IAF braveheart Abhinandan Varthaman, Kupwara district on Fri- on higher reaches of d ay . Jammu and Kashmir who was captured by the Pakistani forces after an Security forces from March 2 after- launched a cordon and noon (Saturday). areal dogfight on Wednes- day morning, many search operation in north "Expect moderate Kashmir's Kralgund vil- rain/snow on higher sought to know as to what forced Islamabad to re- lage in Handwara follow- reaches of Jammu and ing information about the turn him to India after Kashmir regions from presence of militants keeping him in captivity News agency quoted of- the security forces ad- this evening to 4th there, the officials said for nearly 59 hours. -

Press Information Bureau Government of India ***** Maps of Newly Formed Union Territories of Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh, with the Map of India

Press Information Bureau Government of India ***** Maps of newly formed Union Territories of Jammu Kashmir and Ladakh, with the map of India New Delhi, November 2, 2019 On the recommendation of Parliament, the President effectively dismantled Article 370 of the Indian Constitution and gave assent to the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act, 2019. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi and supervision of Union Home Minister Shri Amit Shah, the former state of Jammu & Kashmir has been reorganized as the new Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the new Union Territory of Ladakh on 31st October 2019. The new Union Territory of Ladakh consists of two districts of Kargil and Leh. The rest of the former State of Jammu and Kashmir is in the new Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. In 1947, the former State of Jammu and Kashmir had the following 14 districts - Kathua, Jammu, Udhampur, Reasi, Anantnag, Baramulla, Poonch, Mirpur, Muzaffarabad, Leh and Ladakh, Gilgit, Gilgit Wazarat, Chilhas and Tribal Territory. By 2019, the state government of former Jammu and Kashmir had reorganized the areas of these 14 districts into 28 districts. The names of the new districts are as follows - Kupwara, Bandipur, Ganderbal, Srinagar, Budgam, Pulwama, Shupian, Kulgam, Rajouri, Ramban, Doda, Kishtivar, Samba and Kargil. Out of these, Kargil district was carved out from the area of Leh and Ladakh district. The Leh district of the new Union Territory of Ladakh has been defined in the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization (Removal of Difficulties) Second Order, 2019, issued by the President of India, to include the areas of the districts of Gilgit, Gilgit Wazarat, Chilhas and Tribal Territory of 1947, in addition to the remaining areas of Leh and Ladakh districts of 1947, after carving out the Kargil District. -

Karakorum Himalaya: Sourcebook for a Protected Area

7 Karakorum Himalaya: Sourcebook for a Protected Area Nigel J. R. Allan 8 The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of IUCN. IUCN-The World Conservation Union, Pakistan 1 Bath Island Road, Karachi 75530 © 1995 by IUCN-The World Conservation Union, Pakistan All rights reserved ISBN 969-8141-13-8 Contents Preface v Introduction 1 1 HISTORY Natural Heritage 11 Geology 11 Glaciology 14 Associative Cultural Landscape 17 Local Ideas and Beliefs about Mountains 17 Culturally Specific Communication Networks 20 2 DESCRIPTION AND INVENTORY Physiography and Climate 23 Flora 24 Fauna 25 Juridical and Management Qualities 29 3 PHOTOGRAPHIC AND CARTOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTATION Historial Photographs 33 Large Format Books 33 Landscape Paintings 33 Maps and Nomenclature 34 4 PUBLIC AWARENESS Records of Expeditions 37 World Literature and History 43 Tourism 52 Scientific and Census Reports 56 Guidebooks 66 International Conflict 66 5 RELATED BIBLIOGRAPHIC MATERIALS 69 Author Index 71 Place Index 81 iii iv4 5 Preface This sourcebook for a protected area has its origins in a lecture I gave at the Environment and Policy Institute of the East-West Center in Honolulu in 1987. The lecture was about my seasons of field work in the Karakorum Himalaya. Norton Ginsberg, the director of the Institute, alerted me to the fact that the Encyclopedia Britannica would be revising their entries on Asian mountains shortly and suggested that I update the Karakorum entry. The eventual publication of that entry under my name (Allan 1992), however, omitted most of the literature references I had accumulated. As my reference list continued to expand I decided to order them in some coherent fashion and publish them as a sourcebook to coincide with the IUCN workshop on mountain protected areas in Skardu in September 1994. -

List of Publications

List of Publications: 2021: 1. Majeed, U., Rashid, I., Sattar, A., Allen, S., Stoffel, M., Nüsser, M., & Schmidt, S. (2021). Recession of Gya Glacier and the 2014 glacial lake outburst flood in the Trans-Himalayan region of Ladakh, India. Science of The Total Environment, 756, 144008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144008 [IF- 6.5] 2020: 2. Rashid, I., & Majeed, U. (2020). Retreat and geodetic mass changes of Zemu Glacier, Sikkim Himalaya, India, between 1931 and 2018. Regional Environmental Change, 20(4), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01717-3 [IF- 3.4 ] 3. Rashid, I., Majeed, U., Aneaus, S., Cánovas, J. A. B., Stoffel, M., Najar, N. A., ... & Lotus, S. (2020). Impacts of Erratic Snowfall on Apple Orchards in Kashmir Valley, India. Sustainability, 12(21), 9206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219206 [IF- 2.5 ] 4. Murtaza, K. O., Dar, R. A., Paul, O. J., Bhat, N. A., & Romshoo, S. A. (2020). Glacial geomorphology and recent glacial recession of the Harmukh Range, NW Himalaya. Quaternary International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.044 [IF- 2] 5. Romshoo, S. A., Amin, M., Sastry, K. L. N., & Parmar, M. (2020). Integration of social, economic and environmental factors in GIS for land degradation vulnerability assessment in the Pir Panjal Himalaya, Kashmir, India. Applied Geography, 125, 102307.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102307 [IF- 3.5 ] 6. Rashid, I., & Aneaus, S. (2020). Landscape transformation of an urban wetland in Kashmir Himalaya, India using high-resolution remote sensing data, geospatial modeling, and ground observations over the last 5 decades (1965–2018). -

Dispute Over the Kashmir Region State of India V

Dispute Over the Kashmir Region State of India v. State of Pakistan International Court of Justice Case summary Historical Background Pleadings Complaint Answer Stipulations Witnesses Witness/Exhibits Listing Prosecution Witnesses: Ishita Naksh June Smiths Hamza Ilyas Defense Witnesses: Aisha Hussain Ismail Ghulam Fahad Sareer Exhibits Exhibit A: Balakot attack Exhibit B: Indian jet struck down Exhibit C: Closing schools in Kashmir Exhibit D: Pulwama suicide bombing Exhibit E: Casualties in Kashmir Exhibit F: Map of the Kashmir and Jammu region Exhibit G: Famine in a Saffron farm CASE SUMMARY This Case Summary is not used as evidence in the case but rather is provided for background purposes only. The beginning of the conflict in the Kashmir region between the State of India and the State of Pakistan happened since their independence from Britain in 1947. Since then, the two countries have fought three wars and undergone several conflicts over Kashmir. However, the incident that triggered the two nations in recent years was the Pulwama attack in February 2019. On February 14th, 2019, a quarter past three, a car ran into a bus that held a convoy of the Central Reserve Police Force (CPRF), India’s largest central armed police force. The forces were carrying security personnel on the Jammu-Srinagar National Highway when the car hit the bus. After a moment, the car exploded, killing 40 paramilitary police officers inside the bus. It was later identified that the car was a suicide bomb set by a Pakistan-based Islamist terrorist group terrorist called Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM). The Indian government immediately started an investigation into the attack. -

Wing Commander to Return Today

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 Published From WORLD 12 SPORT 14 DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL A HIGHLY STRATEGIC US-N KOREA TALKS END KL RAHUL PLACED BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR CORRIDOR ABRUPTLY WITHOUT DEAL 6TH IN T20 RANKINGS CHANDIGARH DEHRADUN Late City Vol. 155 Issue 58 LUCKNOW, FRIDAY MARCH 1, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable WANTED TO WORK WITH RAY:} GULZAR} 13 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com Wing Commander to return today IAF: Pak mission achieved, Imran says release a gesture of peace; India asserts it can’t be bargaining chip up to Govt to release proof PNS n ISLAMABAD/NEW DELHI Khan said. The announcement strate our capability and will. WELCOME BACK ABHINANDAN! was greeted by thumping of “We did not want to inflict any day after India demanded desks by Pakistani lawmakers. casualty on India as we want- 2 Pakistan Prime Minster Imran Khan on Thursday announced that Aimmediate release of an The Indian Air Force on ed to act in a responsible man- Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman will be released on IAF pilot who landed in Thursday said it is very happy ner.” Friday as a gesture of peace and the ‘first step’ to open negotiations Pakistan detention on that captured pilot Wing He warned if India moved with India Wednesday following an aeri- Commander Abhinandan is ahead with the “aggression”, 2 The decision comes amid report that the Indian Government al engagement by air forces of returning home but dismissed Pakistan will be forced to retal- reportedly decided that Varthaman cannot be a bargaining chip and the two countries, Pakistan suggestions it was a goodwill iate and urged the Indian lead- New Delhi will not strike any deal with Islamabad for his release Prime Minster Imran Khan on gesture, insisting it was in line ership not to push for escala- 2 The Indian Air Force said it is very happy that captured pilot Wing Thursday announced that with the Geneva Conventions. -

HZ X 4`^^R Uvc E`

!!% =& ( #1 &) !1 &) VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqBVQWBuxy( "#$% &++&, &'()#* &'-#. ,? 3 ," 8> <3 38 " ! " # ""#$!#% %#%#% "<33<3 38? <8 9 67 3 , #&#%%# " !/6 4@ A ! ( ))& #& &'()&*'+,'&(")-."/0'1"$2 R Khan said. The announcement strate our capability and will. was greeted by thumping of “We did not want to inflict any ! day after India demanded desks by Pakistani lawmakers. casualty on India as we want- Aimmediate release of an The Indian Air Force on ed to act in a responsible man- ! " # $ && # & #$ IAF pilot who landed in Thursday said it is very happy ner.” ' ! ( ) L( )M ) Pakistan detention on that captured pilot Wing He warned if India moved ! Wednesday following an aeri- Commander Abhinandan is ahead with the “aggression”, ) , al engagement by air forces of returning home but dismissed Pakistan will be forced to retal- )& $ # #!! ) the two countries, Pakistan suggestions it was a goodwill iate and urged the Indian lead- & && & &# ( & Prime Minster Imran Khan on gesture, insisting it was in line ership not to push for escala- ' )) ) )& ! ebunking Pakistan claims Thursday announced that with the Geneva Conventions. tion as war is not solution to " # ! # Dthat F-16s were not used in Wing Commander “We are very happy any problem. !! !&& !. ! & the offensive against Indian Abhinandan Varthaman will be Abhinandan will be freed Warning that “any miscal- , " military targets in Jammu & released on Friday as a gesture tomorrow and look forward to culation” from India would Kashmir on Wednesday morn- !" ! of peace and the “first step” to his return,” Air Vice Marshal R result in “disaster”, he said, ! . & & ing, the Indian Air Force on #$ % %&' ) open negotiations with India. -

SOUTH ASIA Post-Crisis Brief

SOUTH ASIA Post-Crisis Brief June 2019 Table of Contents Contributors II Introduction IV Balakot: The Strike Across the Line 1 Vice Admiral (ret.) Vijay Shankar India-Pakistan Conflict 4 General (ret.) Jehangir Karamat Lessons from the Indo-Pak Crisis Triggered by Pulwama 6 Manpreet Sethi Understanding De-escalation after Balakot Strikes 9 Sadia Tasleem Signaling and Catalysis in Future Nuclear Crises in 12 South Asia: Two Questions after the Balakot Episode Toby Dalton Pulwama and its Aftermath: Four Observations 15 Vipin Narang The Way Forward 19 I Contributors Vice Admiral (ret.) Vijay Shankar is a member of the Nuclear Crisis Group. He retired from the Indian Navy in September 2009 after nearly 40 years in service where he held the positions of Commander in Chief of the Andaman & Nicobar Command, Commander in Chief of the Strategic Forces Command and Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet. His operational experience is backed by active service during the Indo-Pak war of 1971, Operation PAWAN and as chief of staff, Southern Naval Command during Operation ‘VIJAY.’ His afloat Commands include command of INS Pa- naji, Himgiri, Ganga and the Aircraft Carrier Viraat. He is the recipient of two Presidential awards. General (ret.) Jehangir Karamat is a retired Pakistani military officer and diplomat and member of the Nuclear Crisis Group. He served in combat in the 1965 and 1971 India-Pakistan wars and eventually rose to the position of chairman of the Pakistani Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee before retiring from the armed forces. Karamat was the Pakistani ambassador to the United States from November 2004 to June 2006. -

UG CLAT 2020 – Sample Paper 1 English Language

UG CLAT 2020 – Sample paper 1 English Language Each set of questions in this section is based on a single passage. Please answer each question on the basis of what is stated or implied in the corresponding passage. In some instances, more than one option may be the answer to the question; in such a case, please choose the option that most accurately and comprehensively answers the question. 1. In a letter written in January 1885 to his friend Pramatha Chaudhuri, Tagore spoke of the tension in his own mind between the contending forces of East and West. ‘I sometimes detect in myself,’ he remarked, ‘a background where two opposing forces are constantly in action, one beckoning me to peace and cessation of all strife, the other egging me on to battle. It is as though the restless energy and the will to action of the West were perpetually assaulting the citadel of my Indian placidity. Hence this swing of the pendulum between passionate pain and calm detachment, between lyrical abandon and philosophising between love of my country and mockery of patriotism, between an itch to enter the lists and a longing to remain wrapped in thought.’ Tagore’s mission to synthesise East and West was part personal, part civilizational. In time it also became political. In the early years of the twentieth century, the intelligentsia of Bengal was engulfed by the swadeshi movement, where protests against British rule were expressed by the burning of foreign cloth and the rejection of all things western. After an initial enthusiasm for the movement, Tagore turned against it. -

P17 2 Layout 1

Friday 17 International Friday, March 1 , 2019 An Indian pilot captured in Pakistan becomes face of escalating conflict Varthaman - a hero in India, a trump card for Islamabad NEW DELHI: An Indian pilot shot down over swollen and sporting bruises, but otherwise Pakistan and paraded by his captors has be- collected and calm, that was most seized upon come a hero in his own country, a trump card in both India and Pakistan. In it, he thanks the for Islamabad and perhaps the key to bringing “thorough gentlemen” who rescued him from the arch-rivals back from the brink. Wing Com- the mob and compliments the tea as “fantastic”. mander Abhinandan Varthaman was in a MiG “This is what I would expect my army to be- jet that India said was shot down on Wednes- have as, and I’m very impressed by the Pak- day as he chased Pakistan warplanes over the istani army,” he said, his eye visibly swollen rivals’ disputed Kashmir border. above an impressive handlebar moustache. It Footage of him being beaten and interro- was unclear if he had been coerced to speak. gated has since gone viral in India and Pakistan. That video was widely shown on Pakistani tel- The incident has sparked fears that the show- evision, with still images used on the front page down between the two countries-who have of many newspapers. “Indian pilot thanks Pak fought two wars over Kashmir-could spiral out Army for saving him from mob,” read a front of control. But Pakistan said yesterday it was page headline in the English-language daily ready to hand Varthaman back “if it leads to de- Express Tribune.