Profile of North Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVISED HAMILTON MUNICIPAL HERITAGE COMMITTEE REPORT 14-009(A) 12:00 P.M

REVISED HAMILTON MUNICIPAL HERITAGE COMMITTEE REPORT 14-009(a) 12:00 p.m. Thursday, August 21, 2014 Council Chambers 71 Main Street West Present: A. Denham-Robinson (Chair), Councillor M. Pearson, M. Adkins, W. Arndt, P. Wilson, W. Furlan, S. Nowak Absent: Councillor B. McHattie – City Business Councillor L. Ferguson – City Business K. Wakeman, W. Rosart, R. Sinclair THE HAMILTON MUNICIPAL HERITAGE COMMITTEE PRESENTS REPORT 14- 009(a) AND RESPECTFULLY RECOMMENDS: 1. Implementation of the Recommendations of the Downtown Built Heritage Inventory Project (PED14191) (a) That the properties listed in Schedule 1 of Appendix “A” attached hereto to the Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee Report 14-009(a) be included in the Register of Property of Cultural Heritage Value or Interest as non- designated properties; (b) That staff be directed to add the properties listed in Schedule 2 of Appendix “A” attached hereto to the Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee Report 14-009(a) to the staff’s work program for designation; (c) That Schedule 3 of Appendix “A” attached hereto to the Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee Report 14-009(a) be approved as amended to include the Candidates for Designation; PLANNING COMMITTEE – September 16, 2014 Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee August 21, 2014 Report 14-009(a) Page 2 of 2 (d) That staff be directed to prepare a Capital Budget Submission to be brought forward in the 2015 Budget Deliberations to address the work program for designation, as per Schedule 3 of Appendix “A” attached hereto to the Municipal -

Hamilton Port Authority

THERE’S LOTS HAPPENING IN THE NORTH END! Tell us about your upcoming events, advertise your business or give us your feedback in our Letters to The Editor column. We’re looking for more people to help us put your Newspaper together. What do you like to do? Report on events or interview people? Maybe help with proof reading? Email [email protected] JANUARY 2019 | VOLUME 1 | [email protected] | WWW.NORTHENDBREEZES.COM | @NORTHENDBREEZES | FACEBOOK.COM/NORTHENDBREEZES would not be out of place in any HAMILTON PORT luxury liner. The exterior of the building is faced with limestone AUTHORITY: panelling and large steel mounted windows that gather light and re- flect the sky in a way that suggests THE BUILDING THAT a watery environment. THINKS IT’S A SHIP In 2012, to mark the 100th an- niversary of the founding of the Harbour trust, the Port Authority, SUBMITTED BY ROBYN GILLAM which replaced the Trust in 2000, There’s no proof that the Hamilton Harbour Com- renewed the building. While pre- missioners wanted a land-based ship for their new serving unique materials used in headquarters when they purchased the site at 601 the original construction, like the Burlington in 1951, but there are plenty of clues. steel doors, some features were upgraded. The outdoor railings While Hamilton architects, Murton and Evans, were replaced with titanium and a did not provide any concept or “vision” for their new commemorative plaque was five-storey office building, they offered a design added to those on the facade of the in the Art Moderne style, rather oldfashioned by building. -

Accessible Pools

Choosing a pool that is most accessible to you In the Hamilton area, we have indoor pools with varying degrees of accessibility. The City of Hamilton website provides links to the pools. Please check the link or call the specific pool you have in mind to see if your accessible needs can be met. http://www.hamilton.ca/CultureandRecreation/Recreation/CentresPoolsArenas Ancaster Aquatic Centre 47 Meadowbook Drive Ancaster, Ontario 905-546-2424, ext. 1061 Description: Chair lift for in and out of pool. Swimming lanes. Temperature: 94oF Communal shower, not fully accessible. Accessible washroom. Change room has a bench with a few bars, small space to turn around in. Plank available. Page - 2 Benetto Community Centre 450 Hughson Street North Hamilton, Ontario 905-546-4944 Description: Water wheel chair for in and out of pool. Beach entry steps and ramp. Accessible shower and washroom. Temperature: 84oF Accessible family change room. Dominic Agostino Riverdale Recreation Centre 150 Violet Drive Stoney Creek, Ontario 905-546-4284 Description: Temperature: 84oF Not deep. 5 feet. Beach entry with railings. Water wheel chair available. Accessible shower and change room, entrance a small space. Page - 3 Huntington Park Recreation Centre 87 Brentwood Drive Hamilton, Ontario 905-546-3122 Description: Two pools: Large Temperature: 84oF Smaller warm water pool. Ramps, stairs and seats in both pools. Accessible shower and family change room. St. Joseph’s Villa Centre 56 Governors Road Dundas, Ontario 905-627-3541, Ext. 2911 Separate website http://www.sjv.on.ca/community- services/pool.html Description: Stairs, ramp and water wheelchair. Accessible washroom and shower. -

H Miltnn Fax (905) 546-4202

Committee of Adjustment CITY HALL 5th Floor- 71 Main Street West Hamilton, ON LSP 4Y5 Telephone (905) 546-2424, ext. 4221 H miltnn Fax (905) 546-4202 AGENDA COMMITTEE OF ADJUSTMENT Date: Thursday, August 21st, 2014 Time: 1:00 p.m. Location: Rooms 192 & 193, 1st floor, Hamilton City Hall Contact: Lesley Dahonick (905) 546-2424, ext. 4144 TIME SUBJECT BY 207 Alderlea Avenue, Glanbrook 1:15 p.m. GL/A-14:194 (Ward 11) Owners Barry & Joanne Lyne Agent A. J. Clarke & Associates 1970 Rymal Rd. E., Glanbrook Ltd. 1:20 p.m. GL/A-14:198 (Ward 11) Owner Multi-Area Developments Inc. (A. DeSantis/D. DeSantis) SC/B-14:72 265 Cedardale Avenue, Stoney Creek 1:25 p.m. (Ward 10) Owner Lakvinder Sihra 11 Aikman Ave., Hamilton HM/A-14:205 1:30 p.m. (Ward 3) Owner Hossein Kiani Khalkhal Agent IBI Group(M. Johnston) SC/A-14:200 98 Shoreview Place, Stoney Creek 1:35 p.m. (Ward 10) Owner King-Tis Investment Limited c/o David Horwood Agent IBI Group 2673 King St. E., Hamilton 1:40 p.m. HM/A-14:203 (Ward 3) Owner 2673 King St. E., Co- Tenancy c/o David Horwood Change of Agent IBI Group (M. Johnston) conditions 552 & 554 Mary St., Hamilton 1:45 p.m. (Ward 2) Owners George Rice & Mark HM/B-14:18 Gruwer 1391 Brock Rd., Flamborough Agent Rosa Rocha 1:50 p.m. FL/B-14:68 (Ward 14) Applicants G. & D Lammers 1391 Brock Rd., Flamborough Agent Rosa Rocha 1:50 p.m. -

AYS Aug 15.Indd

CITY OF HAMILTON Notices 905.546.CITY(2489) www.hamilton.ca @cityofhamilton 519 RESIDENTS CALL 519.647.2577 | CAMPBELLVILLE RESIDENTS CALL 905.634.2971 NOTICES PUBLIC NOTICE TO PERMANENTLY CLOSE A PORTION OF THE ROAD ALLOWANCE TO MOTORIZED TRAFFIC ON HUGHSON STREET NORTH IN THE CITY OF HAMILTON Notice is hereby given pursuant to City of Hamilton By-law 04-299 to establish procedures, including the giving of notice to the public that the Council of the City of Hamilton proposes to pass a By-law to permanently close to motorized traffic a portion of Hughson Street North in the City of Hamilton. A copy of the drawing showing the lands to be affected may be seen in the Transportation Division, 77 James Street North, Suite 400, Hamilton. Please address inquires to the attention of Steve Molloy (905) 546-2424 extension 2975 or [email protected]. On Tuesday September 2, 2014 at 9:30 am, at Hamilton City Hall, 71 Main Street West, Hamilton, the Public Works Committee will hear in person, or by his/her counsel, solicitor or agent any person who claims that his/her lands will be prejudicially affected by the said by-law and who applies to be heard. Any such person who wishes to be heard should make written application by 12:00 noon on Friday August 29, 2014 to the following individual: Lauri Leduc, Legislative Coordinator Public Works Committee 71 Main Street West Hamilton, Ontario L8P 4Y5 (905) 546-2424 Ext.4102 [email protected] This activity is categorized as a Schedule ‘A+’ project, which was identified within the 2008 Council Approved North End Traffic Management Plan that was undertaken according to the Municipal Engineers Association, Municipal Class Environmental Assessment document (June 2000, as amended in 2007). -

06 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

06 bus time schedule & line map 06 Downtown View In Website Mode The 06 bus line (Downtown) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Downtown: 12:21 AM - 11:21 PM (2) Princess Point Loop: 12:00 AM - 11:00 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 06 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 06 bus arriving. Direction: Downtown 06 bus Time Schedule 33 stops Downtown Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:20 AM - 10:17 PM Monday 5:24 AM - 11:21 PM Princess Point Loop 300 Longwood Road, Hamilton Tuesday 12:21 AM - 11:21 PM Macklin at Kay Drage Park Wednesday 12:21 AM - 11:21 PM 101 Macklin Street North, Hamilton Thursday 12:21 AM - 11:21 PM At 100 Macklin Friday 12:21 AM - 11:21 PM 99 Macklin Street, Hamilton Saturday 12:21 AM - 11:20 PM Macklin at Coronation Arena 81 Macklin Street, Hamilton Macklin at Glen 9 MacKlin Street North, Hamilton 06 bus Info Direction: Downtown Longwood at King Stops: 33 10 Longwood Road South, Hamilton Trip Duration: 21 min Line Summary: Princess Point Loop, Macklin at Kay Longwood at Marion Drage Park, At 100 Macklin, Macklin at Coronation 100 Longwood Road, Hamilton Arena, Macklin at Glen, Longwood at King, Longwood at Marion, Longwood Opposite Longwood Opposite Mcmaster Innovation Park Mcmaster Innovation Park, Aberdeen Opposite 270 Longwood Road South, Hamilton Longwood, Aberdeen at Studholme, Aberdeen at Chedoke, Aberdeen at Dundurn, Aberdeen at Aberdeen Opposite Longwood Cottage, Aberdeen at Undermount, Aberdeen at 611 Aberdeen Avenue, Hamilton Kent, Aberdeen at Spruceside, -

Diabetes; Foot Care Resources in the 905 Area Code

8 Foot care resources in the 905 area code Foot care resources in the 905 area code This handout will help you find information about foot care in the Hamilton-Wentworth region. It does not list all of the resources in this area. For more resources, check the yellow pages in the telephone book or talk to your health care provider. Foot and nail care Chiropody Clinics Best Foot Forward Program • OHIP covered for people with (2 locations) diabetes and chronic kidney disease. St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton • Need referral through your – King Campus dialysis centre. Hemodialysis Unit – Clinic Room 1 2757 King Street East • Foot care and nail trimming, Hamilton, Ontario treatment for corns and calluses, thick ingrown or St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton discoloured nail toe nails, small – Charlton Campus foot ulcers and skin infections. Level 4 Marian Wing 50 Charlton Avenue East Hamilton, Ontario The West Mountain Foot Care Clinic • Call for an appointment. 536 Upper James Street • Fee charged for services. Hamilton, Ontario 905-538-6800 • Nail surgery, callous reduction, ulcer treatment and orthotics. © Hamilton Health Sciences and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, 2008 PD 3787 – 06/2014 dpc/pted/DiabetesResources905Area-pe.doc ____________________________________________________________________________ dt/June 12, 2014 2 7 Foot care resources in the 905 area code Foot care resources in the 905 area code Chiropody Clinics (continued) Notes St. Joseph’s Home Care • Fee charged for service. (in-home foot care services) ______________________________________________________ • Available to any age. 905-522-5887, ext. 2236 • Assessment, care and advice for ______________________________________________________ people with problems looking after, eg., elderly, diabetes. -

Who Was Susan Bennetto?

MARCH 2020 | VOLUME 3 | [email protected] | WWW.NORTHENDBREEZES.COM | @NORTHENDBREEZES | FACEBOOK.COM/NORTHENDBREEZES name? Well… I knew it used to be called WHO WAS SUSAN Centennial and that a generation after it had been built it was amalgamated with its neighboring middle school, ‘Bennet- BENNETTO? to’. But who was Bennetto? I assumed it SUBMITTED BY FRANCESCA ALFANO, was a stuffy old Superintendent. That trip BENNETTO TEACHER to Reggio Emilia where students had re- searched their namesake and written about it made me curious. I started with a google search and then a dove into the Hamilton – Wentworth School Board Archives and the City of Hamilton archives housed in the Hamilton Public Library. The records are quite interesting. Our namesake, Susan Bennetto, had a re- markable career. Born in England in 1850 and immigrating to the great port city of Hamilton shortly afterward she grew up with a seamstress mother and carpenter father on Cannon Street. By the age of 17 she graduated with a First Class teaching certificate and earned an impressive $200 A brief history: The New Horizons Thrift per year. Establishing a strong reputation, WALKABOUT COMMUNITY: Store has been a the staple “to go to” thrift she was assigned to Canada’s first graded shop which was established here in Hamil- public school, Central School on Hunter ton’s North End since the late 1970’s until On a recent trip to my ancestral homeland, Street West. Susan E. Bennetto left Ham- NEW HORIZONS January of 2008 when ownership was tak- Italy, I had the opportunity to visit early ilton briefly and returned to find out that SUBMITTED BY KEN HIRTER en over by the Welcome Inn Community childhood centres and schools working in a new school was being erected on the Center. -

Hamilton Municipal Heritage Committee Agenda Package

City of Hamilton HAMILTON MUNICIPAL HERITAGE COMMITTEE AGENDA Meeting #: 20-003 Date: July 3, 2020 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Due to the COVID-19 and the Closure of City Hall All electronic meetings can be viewed at: City’s Website: https://www.hamilton.ca/council- committee/council-committee- meetings/meetings-and-agendas City’s YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/user/InsideCityofHa milton or Cable 14 Loren Kolar, Legislative Coordinator (905) 546-2424 ext. 2604 1. CEREMONIAL ACTIVITIES 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (Added Items, if applicable, will be noted with *) 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 4. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING 4.1 February 21, 2020 5. COMMUNICATIONS 5.1 Correspondence from Daniel Coleman respecting 50-54 Sanders Blvd., Hamilton Recommendation: Be received 5.2 Correspondence from Anne Newbigging respecting 558 Wilson St. East proposed inclusion on the Municipal Heritage Register (referred from May 13, 2020 meeting of Council) Recommendation: Be received 6. DELEGATION REQUESTS 7. CONSENT ITEMS 7.1 Heritage Permit Applications: Delegated Approvals 7.1.a Heritage Permit Application HP2020-004: Proposed alteration of Historic Barn and Landscaping at 77 King Street West, Stoney Creek (Ward 9) (By- law No. 3419-91) 7.1.b Heritage Permit Application HP2020-005: Proposed Alteration of Sunday School and Restoration of Stained-Glass Windows of the Church's Chancel at 10 Tom Street, Hamilton (Ward 1) (By-law No. 96-148) 7.1.c Heritage Permit Application HP2020-006: Proposed Alteration of Bay Window Roof Replacement, Porch and Brickwork at 17 Victoria Street, Dundas (Ward 13) (By-law No. -

HAMILTON, Z Duncan .1 Mrs, Grocer Ilunter England Richard, Restaurant 101 �ONTARIO

Al,PHABETICAI BUSINESS TURECTORY. Z A49 ALPHABPTICAL BUSINESS DIRECTORY. A49 HAMILTON —Continued. Egener Charles, hotel I7Market Syr Itepairing a Duff J Je Son, grocers etc 210 York Elder George. grocer 121 Rebecca done onabortest notion. Yelepimsar•_ Ne. SS. Find-Claw+ work guaranteed, pg. fto Duff W A II, barrister 67 James 8 Electric Supply Co, Lowe & X» CO I r Duffy E MN, milliner 139 James n Farrell Proprs 40 James a(tiee adv •M I&D FULIMIELM o Duffy John, hotel 87 Cannon e Elliott John, barber 149 James n Dufton Jas, contrIctor 222 Barton e Elliott Robert, livery 178 Elgin ELECTRIC SUPPLY CO. QC Den. Wiman&Co,mercantile agency Ellis D G, broker 14 Main e 40 JAMES STREET, SOUTH, 1.1 11 Hughson s Emory V. physician 42 Macnab s tele 0 Duncan B•os, who tels 71 King w England F, barber 63 James n HAMILTON, Z Duncan .1 Mrs, grocer Ilunter England Richard, restaurant 101 ONTARIO. Annunciators, Burgular Alarms, Electric det Duncan Lithographing Co, 17James Stuart w Ge Lighting, Electric and hile, hanimi Batteries, Vire, Push Buttens, Factory and Private Telephones, hpeaking Tunce, Telegraph U.,2 ma north Ennis George, 159 York instruniente, Medical Batteriea, Watchmen's Clocks, Electric Light Fixtures, etc. n Dl. Duncan Robert, books & stationery Ennis J & Co, printers 13Macnab ESTIMATES GIVEN FOR ALL CLASSES OF 17 James n Ennis & Co. piano innfrs 9 Bay n ELECTRICAL WORK Pi> Z Dunham F T, painter 32 James s Erdman C Mrs, grocery 220 Well- CC Dunlop David, harness 88 John PI ington n al Dunlop Jas flour & feed 127 John s Erwood Joseph, laundry 48 South McCallum& Hall 74' Dunlop Robert, insurance 70 King e Eustice John, groeer etc 205 John s c •wo Dunn MMiss,dressmaker 171Park n Evans C Mrs, restaurant II York gx Dunn C M, veter:nary surgeon etc Evans G 11, crockery 110 James n F URNITURE 127 James s Evans L Mis, groc. -

Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant - Diabetes Education Program - Referral Form Serving Hamilton, Niagara, Haldimand, Norfolk, Burlington and Brant

Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant - Diabetes Education Program - Referral Form Serving Hamilton, Niagara, Haldimand, Norfolk, Burlington and Brant Referring Health Service Provider (or stamp) Referral Date: mm/dd/yyyy Name: ______________________________________________________ Niagara Zone: Fax - 1-905-682-3622 Billing #: _____________________________________________________ Hamilton/Burlington Zone: Fax - 1-905-521-6128 Haldimand Norfolk Brant Zone: Fax - 1-519-751-5862 Phone #: ____________________________________________________ Direct Referral – see back Signature: ___________________________________________________ Patient Information Name: ________________________________________________ Gender:____________ DOB: ___mm/dd/yyyy______ Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________ City: ___________________________________ Postal Code: _________________ Health Card #: ________________________ Contact Number: __________________________ Alternate Contact: _________________________________________________ Primary Language Spoken: ________________________________________ Translation Required? Yes No Primary Care Provider: _________________________________________ Reason for Referral: Insulin Start New Diagnosis of Diabetes Is this referral urgent? YES NO Other: Type of Diabetes: Type 1 MDI Type 1 Pump Type 2 Pre-diabetes At Risk Paediatric Gestational Pregnant Type 1 Pregnant Type 2 Other # wks pregnant # Weeks # Weeks Relevant Medical History OR Most Recent Clinic Note Attached Labs: Please -

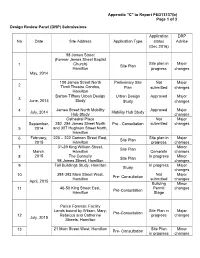

Appendix "C" to Report PED13137(B) Page 1 of 3 Design Review Panel (DRP) Submissions

Appendix "C" to Report PED13137(b) Page 1 of 3 Design Review Panel (DRP) Submissions Application DRP No Date Site Address Application Type status Advice (Dec 2016) 98 James Street (Former James Street Baptist Church) Site plan in Major 1 Site Plan Hamilton progress changes May, 2014 108 James Street North Preliminary Site Not Major 2 Tivoli Theatre Condos, Plan submitted changes Hamilton Barton-Tiffany Urban Design Urban Design Approved Major 3 June, 2014 Study Study changes James Street North Mobility Approved Major 4 July, 2014 Mobility Hub Study Hub Study changes Cathedral Place Not Major September, 252, 254 James Street North Pre - Consultation submitted changes 5 2014 and 307 Hughson Street North, Hamilton February, 220 – 222 Cannon Street East, Site plan in Major 6 Site Plan 2015 Hamilton progress changes 31-39 King William Street, Minor 7 Site Plan March, Hamilton Complete changes 2015 The Connolly In progress Minor 8 Site Plan 98 James Street, Hamilton changes Tall Buildings Study, Hamilton In progress Major 9 Study changes 388-392 Main Street West, Not Major 10 Pre- Consultation Hamilton submitted changes April, 2015 Building Minor 11 46-50 King Street East, Permit changes Pre-Consultation Hamilton Stage Police Forensic Facility Lands bound by Wilson, Mary, Site Plan in Major Pre-Consultation 12 Rebecca and Catherine progress changes July, 2015 Streets, Hamilton 21 Main Street West, Hamilton Site Plan Minor 13 Pre- Consultation in progress changes Appendix "C" to Report PED13137(b) Page 2 of 3 Not Major 14 41 Stuart Street, Hamilton