Melissasalmi Pain Over Pleasure Bathesis FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just How Nasty Were the Video Nasties? Identifying Contributors of the Video Nasty Moral Panic

Stephen Gerard Doheny Just how nasty were the video nasties? Identifying contributors of the video nasty moral panic in the 1980s DIPLOMA THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie Programme: Teacher Training Programme Subject: English Subject: Geography and Economics Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, May 2019 i Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic paper is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this paper to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Stephen G. Doheny “m.p.” Köttmannsdorf: 1st May 2019 Dedication I I would like to dedicate this work to my wife and children, for their support and understanding over the last six years. -

From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film)

Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) by Agnieszka Mlynarz A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Studies Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Agnieszka Mlynarz, April, 2017 ABSTRACT Maple Syrup Gore: From Sexploitation to Canuxploitation (Representations of Gender in the Canadian ‘Slasher’ Film) Agnieszka Mlynarz Advisor: University of Guelph, 2017 Professor Alan Filewod This thesis is an investigation of five Canadian genre films with female leads from the Tax Shelter era: The Pyx, Cannibal Girls, Black Christmas, Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS, and Death Weekend. It considers the complex space women occupy in the horror genre and explores if there are stylistic cultural differences in how gender is represented in Canadian horror. In examining variations in Canadian horror from other popular trends in horror cinema the thesis questions how normality is presented and wishes to differentiate Canuxploitation by defining who the threat is. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. Paul Salmon and Dr. Alan Filewod. Alan, your understanding, support and above all trust in my offbeat work ethic and creative impulses has been invaluable to me over the years. Thank you. To my parents, who never once have discouraged any of my decisions surrounding my love of theatre and film, always helping me find my way back despite the tears and deep- seated fears. To the team at Black Fawn Distribution: Chad Archibald, CF Benner, Chris Giroux, and Gabriel Carrer who brought me back into the fold with open arms, hearts, and a cold beer. -

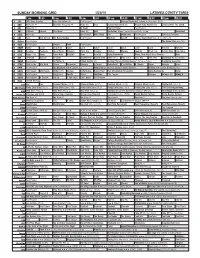

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Re-Reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis Ebook

RE-READING THE MONSTROUS-FEMININE : ART, FILM, FEMINISM AND PSYCHOANALYSIS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Chare | 268 pages | 18 Sep 2019 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9781138602946 | English | London, United Kingdom Re-reading the Monstrous-Feminine : Art, Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis PDF Book More Details Creed challenges this view with a feminist psychoanalytic critique, discussing films such as Alien, I Spit on Your Grave and Psycho. Average rating 4. Name required. Proven Seller with Excellent Customer Service. Enlarge cover. This movement first reached success in the Pitcairn Islands, a British Overseas Territory in before reaching the United States in , and the United Kingdom in where women over thirty were only allowed to vote if in possession of property qualifications or were graduates of a university of the United Kingdom. Sign up Log in. In comparison, both films support the ideas of feminism as they depict women as more than the passive or lesser able figures that Freud and Darwin saw them as. EMBED for wordpress. Doctor of Philosophy University of Melbourne. Her argument that man fears woman as castrator, rather than as castrated, questions not only Freudian theories of sexual difference but existing theories of spectatorship and fetishism, providing a provocative re-reading of classical and contemporary film and theoretical texts. Physical description viii, p. The Bible, if read secularly, is our primal source of horror. The initial display of women as villains despite the little screen time will further allow understanding of the genre of monstrous feminine and the roles and depths allowed in it which may or may not have aided the feminist movement. -

The Cultural Significance of Web-Based Exchange Practices

The Cultural Significance of Web-Based Exchange Practices Author Fletcher, Gordon Scott Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2111 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365388 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Cultural Significance of Web-based Exchange Practices Gordon Scott Fletcher B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts, Media and Culture Faculty of Arts Griffith University September 2004 2 Abstract This thesis considers the cultural significance of Web-based exchange practices among the participants in contemporary western mainstream culture. The thesis argues that analysis of these practices shows how this culture is consumption oriented, event-driven and media obsessed. Initially, this argument is developed from a critical, hermeneutic, relativist and interpretive assessment that draws upon the works of authors such as Baudrillard and De Bord and other critiques of contemporary ‘digital culture’. The empirical part of the thesis then examines the array of popular search terms used on the World Wide Web over a period of 16 months from September 2001 to February 2003. Taxanomic classification of these search terms reveals the limited range of virtual and physical artefacts that are sought by the users of Web search engines. While nineteen hundred individual artefacts occur in the array of search terms, these can classified into a relatively small group of higher order categories. Critical analysis of these higher order categories reveals six cultural traits that predominant in the apparently wide array of search terms; freeness, participation, do-it-yourself/customisation, anonymity/privacy, perversion and information richness. -

Isona Rigau Production Designer

Isona Rigau Production Designer Credits Film Production Company Notes DALI LAND Zephyr Films Dir: Mary Harron 2021 Featuring: Ben Kingsley, Ezra Miller VENOM: LET THERE Marvel Entertainment / Dir: Andy Serkis BE CARNAGE Pascal Pictures / Sony Prods: Avi Arad, Kelly Marcel, Amy Pascal, STANDBY ART Pictures Matt Tolmach DIRECTOR - 2ND UNIT Production Designer: Oliver Scholl 2021 Supervising Art Director: Tom Brown NO TIME TO DIE Eon Productions / MGM Dir: Cary Joji Fukunaga STANDBY ART Prods: Barbara Broccoli, Michael G. Wilson DIRECTOR - 2ND UNIT Production Designer: Mark Tildesley 2020 Supervising Art Director: Chris Lowe LAST CHRISTMAS Calamity Films / Feigco Dir: Paul Feig STANDBY ART Entertainment / Universal Producers: Paul Feig, Jessie Henderson, DIRECTOR Pictures David Livingstone, Emma Thompson 2019 Production Designer: Gary Freeman Supervising Art Director: Tom Still LA HIJA DE UN Oberón Cinematográfica / Dir: Belén Funes LADRÓN (A THIEF’S BTeam Pictures / Movistar+ Prod: Antonio Chavarrías DAUGHTER) Production Designer: Marta Bazaco ART DIRECTOR * Won: 3 Gaudí Awards including Best 2019 Non-Catalan Language Film, and nominated for a further 10 * Nominated: 2 Goya Awards (won for Best New Director) * Nominated: Best Film, San Sebastián International Film Festival 2019 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes TERMINATOR: DARK Lightstorm Entertainment / Dir: Tim Miller FATE Skydance Media / Prods: James Cameron, Howard -

The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: an Analysis of The

THE CURIOUS CASE OF CHINESE FILM CENSORSHIP: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM ADMINISTRATION REGULATIONS by SHUO XU A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shuo Xu Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gabriela Martínez Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Daniel Steinhart Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2017 ii © 2017 Shuo Xu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Shuo Xu Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication December 2017 Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations The commercialization and global transformation of the Chinese film industry demonstrates that this industry has been experiencing drastic changes within the new social and economic environment of China in which film has become a commodity generating high revenues. However, the Chinese government still exerts control over the industry which is perceived as an ideological tool. They believe that the films display and contain beliefs and values of certain social groups as well as external constraints of politics, economy, culture, and ideology. This study will look at how such films are banned by the Chinese film censorship system through analyzing their essential cinematic elements, including narrative, filming, editing, sound, color, and sponsor and publisher. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

A History of X: 100 Years of Sex in Film by Luke Ford

A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film By Luke Ford Nowadays, it’s difficult to imagine our lives without the Internet as it offers us the easiest way to access the information we are looking for from the comfort of our homes. There is no denial that books are an essential part of life whether you use them for the educational or entertainment purposes. With the help of certain online resources, such as this one, you get an opportunity to download different books and manuals in the most efficient way. Why should you choose to get the books using this site? The answer is quite simple. Firstly, and most importantly, you won’t be able to find such a large selection of different materials anywhere else, including PDF books. Whether you are set on getting an ebook or handbook, the choice is all yours, and there are numerous options for you to select from so that you don’t need to visit another website. Secondly, you will be able to download A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film pdf in just a few minutes, which means that you can spend your time doing something you enjoy. But, the benefits of our book site don’t end just there because if you want to get a certain by Luke Ford A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film, you can download it in txt, DjVu, ePub, PDF formats depending on which one is more suitable for your device. As you can see, downloading A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film By Luke Ford pdf or in any other available formats is not a problem with our reliable resource. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context

UC Santa Barbara Journal of Transnational American Studies Title Uncovering a Cover: Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6308x270 Journal Journal of Transnational American Studies, 7(1) Author Nilsson, Louise Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/T871030648 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California SPECIAL FORUM Uncovering a Cover: Marketing Swedish Crime Fiction in a Transnational Context LOUISE NILSSON Key to the appeal of Scandinavian crime literature is the stoic nature of its detectives and their peculiarly close relationship with death. One conjures up a brooding Bergmanesque figure contemplating the long dark winter. [. .] Another narrative component just as vital is the often bleak Scandinavian landscape which serves to mirror the thoughts of the characters. ——Jeremy Megraw and Billy Rose, “A Cold Night’s Death: The Allure of Scandinavian Crime Fiction”1 The above quote from the New York Public Library’s website serves as a mise-en-place for introducing Scandinavian crime fiction by presenting the idea of the exotic, mysterious North. A headline on the website associates the phrase “A Cold Night’s Death” with the genre often called Nordic noir. A selection of Swedish book covers is on display, featuring hands dripping with blood, snow-covered fields spotted with red, and dark, gloomy forests. A close-up of an ax on one cover implies that there is a gruesome murder weapon. At a glance it is apparent that Scandinavian crime fiction is set in a winter landscape of death that nevertheless has a seductive allure.