Vce-FN-Spring-2010.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing Conservation Status of Resident and Migrant Birds on Hispaniola with Mist-Netting

Assessing conservation status of resident and migrant birds on Hispaniola with mist-netting John D. Lloyd, Christopher C. Rimmer and Kent P. McFarland Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Norwich, VT, United States ABSTRACT We analyzed temporal trends in mist-net capture rates of resident (n D 8) and overwintering Nearctic-Neotropical migrant (n D 3) bird species at two sites in montane broadleaf forest of the Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic, with the goal of providing quantitative information on population trends that could inform conservation assessments. We conducted sampling at least once annually during the winter months of January–March from 1997 to 2010. We found evidence of declines in capture rates for three resident species, including one species endemic to Hispaniola. Capture rate of Rufous-throated Solitaire (Myadestes genibarbis) declined by 3.9% per year (95% CL D 0%, 7.3%), Green-tailed Ground-Tanager (Microligea palustris) by 6.8% (95% CL D 3.9%, 8.8%), and Greater Antillean Bullfinch (Loxigilla violacea) by 4.9% (95% CL D 0.9%, 9.2%). Two rare and threatened endemics, Hispaniolan Highland-Tanager (Xenoligea montana) and Western Chat-Tanager (Calyptophilus tertius), showed statistically significant declines, but we have low confidence in these findings because trends were driven by exceptionally high capture rates in 1997 and varied between sites. Analyses that excluded data from 1997 revealed no trend in capture rate over the course of the study. We found no evidence of temporal trends in capture rates for any other residents or Nearctic-Neotropical migrants. We do not know the causes of the observed declines, nor can we conclude that these declines are not a purely Submitted 12 September 2015 local phenomenon. -

'RAISED TAIL' BEHAVIOR of the COLLARED TROGON (Trogon

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327919604 "RAISED TAIL" BEHAVIOR OF THE COLLARED TROGON (Trogon collaris) Article · September 2018 CITATION READS 1 126 1 author: Cristina Sainz-Borgo Simon Bolívar University 57 PUBLICATIONS 278 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Censo Neotropical de Aves Acuáticas en Venezuela View project Conteo de bacterias en los alimentadores artificiales de colibries View project All content following this page was uploaded by Cristina Sainz-Borgo on 25 October 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Sainz-Borgo Bolet´ınSAO Vol. 27 - 2018 `Raised Tailed' behavior of the Collared Trogon (No. 1 & 2) { Pag: 1-3 `RAISED TAIL' BEHAVIOR OF THE COLLARED TROGON (Trogon collaris) DESPLIEGUE DE LA COLA LEVANTADA EN EL TROGON ACOLLARADO (Trogon collaris) Cristina Sainz-Borgo1 Abstract The `raised tail' behavior of two pairs of Collared Trogon (Trogon collaris) was observed in the Coastal Range of Venezuela. In both observations, a male and female rapidly raised their tails to a horizontal position and slowly returned them to a vertical hanging position. During these displays, both individuals simultaneously emitted loud calls approximately every 5 seconds, forming a duet. The first display lasted 30 minutes while the second lasted approximately 45 minutes. This `raised tail' behavior has been reported for several species of trogons during courtship and when mobbing a predator. Because there were no predators present during both observations, the described `raised tail' behavior was most likely a courtship display. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Neotropical Birding 24 2 Neotropical Species ‘Uplisted’ to a Higher Category of Threat in the 2018 IUCN Red List Update

>> FEATURE RED LIST 2018 The 2018 IUCN Red List in the Neotropics James Lowen, Hannah Wheatley, Claudia Hermes, Ian Burfield and David Wege Neotropical Birding 21 featured a summary of the key implications for the Neotropics of the 2016 IUCN Red List for birds. This article briefs readers on the main changes from the 2018 update. s part of its role as the IUCN Red List BirdLife’s Red List team updated the Authority for birds, BirdLife International information available for roughly 2,300 species A is responsible for assessing the global worldwide. Globally, this resulted in changes to conservation status of each of the world’s 11,000 the categorisation of 89 species; 58 species were or so bird species, allocating each to a category ‘uplisted’ to a higher category of threat, whilst ranging from Least Concern to Extinct. The latest roughly half that number – 31 species – were update was published in November 2018 (BirdLife ‘downlisted’. In the Neotropics, 13 species were International 2018). Although much more modest uplisted (Fig. 2) and slightly more – 18 – were in reach than the comprehensive update carried downlisted (Fig. 5). Now let’s take a closer look at out in 2016, whose Neotropical dimension was the individual changes, largely using information discussed in Symes et al. (2017), the 2018 revamp made available on BirdLife’s ‘Globally Threatened contains a suite of interesting changes for species Bird Forums’ (8 globally-threatened-bird- occurring in the Neotropical Bird Club region that forums.birdlife.org). Is the picture quite as rosy as are worth drawing to readers’ collective attention. -

(Hispaniolan Trogon) Crossword

All about the Papagayo (Hispaniolan Trogon) Complete the crossword puzzle below 1N E S 2T 3B R L 4P I N E U 5G E 6H E A R 7H 8I N S 9E C T S E 10MA L E V E B 11FO R E S T S 12MO U N T A I N S R T 13YE L L O W 14PA P A G A Y O 15C T N 16HA I T I 17EX 18TI N 19CT V 20E L W U 21HI S P A N I O L A O B T D S A Y E S M 22F23RU I T E C D Across Down 1. A structure or place that a bird uses for laying eggs 2. You can plant this to help birds survive. (trees) and raising chicks. (nest) 3. Colour of the Papagayo’s tail. (blue) 4. One type of forest where Hispaniolan Trogon live. 5. Colour of the Papagayo’s back. (green) (pine) 7. Occurs when the place where a place an animal or 6. Often you ______ this bird before you see it in the plant lives is destroyed or extremely changed. For forest. (hear) example, when the trees are cut down and the land is 8. An important food of the Papagayo. (insects) used for something else, like farming or building 10. The sex that has fine black and white markings homes or businesses. (two words with a space) on the wing. (male) (habitat loss) 11. Papagayo and other wildlife need this habitat to 9. -

Guam Crow, Hispaniolan Trogon Dominican Amazons

AFA Funds Study of to th more than 20,000 already raised to assist these endangered species. Guam Crow, Development of a Field Based Hispaniolan Trogon Propagation Program for the and Hispaniolan Trogon. Funding approved - 2 525. Inve tigators: teve Dominican Amazons Amo , Ken Reininger, Jose Ottenwalder by Jack Clinton-Eitniear Jack Clinton-Eitniear and William Hasse. Chairman, Conservation Committee Hispaniola has 73 species ofresident San Antonio, Texas land birds, the largest of any island in the West Indies. Twenty species are During the 13th Annual Convention endemic to Hi paniola. Charles Woods, of the merican Federation of Avicul Ph.D., a researcher from the Florida ture held in eattle Washington 12-16 tate Museum, has conducted extensive ugu t 198 the Board of Directo'r re arch on the Haitian portion of the approved the Conservation Commit i land and Ii ts nine pecies of greatest t recommendation to fund three GUCl1n Crou' con er ation concern. Of the nine, con er ation tudie . eight are oftbill, the exception being Breeding Biology of the to the i land and further document the the Hispaniolan parrot. With the Mariana Crow. Funding approved species' reproductive behavior and majority ofspecies that inhabit tropical 3 000. Investigator: Gary A. Michael. inve tigate the po ibility ofe tablishing forests being softbills it is of great Of the 40 true crow in the family th pecies in captivity. A special sub concern that our ability to deal with Corvidae, the Mariana or Guam crow committee of the Conser ation Com them a iculturally i years behind other (Corvus kubaryi) i on of the lea t mittee has been e tabli hed to deal with avian groups uch a parrot waterfowl tudied and onl the Hawaiian crow thi latter element ofthe program. -

Street-Level Green Spaces Support a Key Urban Population of the Threatened Hispaniolan Parakeet Psittacara Chloropterus

Urban Ecosystems https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-021-01119-1 Street-level green spaces support a key urban population of the threatened Hispaniolan parakeet Psittacara chloropterus Matthew Geary1 & Celia J. Brailsford1 & Laura I. Hough1 & Fraser Baker2 & Simon Guerrero3 & Yolanda M. Leon4,5 & Nigel J. Collar6 & Stuart J. Marsden2 Accepted: 28 March 2021 # The Author(s) 2021 Abstract While urbanisation remains a major threat to biodiversity, urban areas can sometimes play an important role in protecting threatened species, especially exploited taxa such as parrots. The Hispaniolan Parakeet Psittacara chloropterus has been extir- pated across much of Hispaniola, including from most protected areas, yet Santo Domingo (capital city of the Dominican Republic) has recently been found to support the island’s densest remaining population. In 2019, we used repeated transects and point-counts across 60 1 km2 squares of Santo Domingo to examine the distribution of parakeets, identify factors that might drive local presence and abundance, and investigate breeding ecology. Occupancy models indicate that parakeet presence was positively related to tree species richness across the city. N-Mixture models show parakeet encounter rates were correlated positively with species richness of trees and number of discrete ‘green’ patches (> 100 m2) within the survey squares. Hispaniolan Woodpecker Melanerpes striatus, the main tree-cavity-producing species on Hispaniola, occurs throughout the city, but few parakeet nests are known to involve the secondary use of its or other cavities in trees/palms. Most parakeet breeding (perhaps 50–100 pairs) appears to occur at two colonies in old buildings, and possibly only a small proportion of the city’s1500+ parakeets that occupy a single roost in street trees breed in any year. -

Adobe PDF, Job 6

Noms français des oiseaux du Monde par la Commission internationale des noms français des oiseaux (CINFO) composée de Pierre DEVILLERS, Henri OUELLET, Édouard BENITO-ESPINAL, Roseline BEUDELS, Roger CRUON, Normand DAVID, Christian ÉRARD, Michel GOSSELIN, Gilles SEUTIN Éd. MultiMondes Inc., Sainte-Foy, Québec & Éd. Chabaud, Bayonne, France, 1993, 1re éd. ISBN 2-87749035-1 & avec le concours de Stéphane POPINET pour les noms anglais, d'après Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World par C. G. SIBLEY & B. L. MONROE Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1990 ISBN 2-87749035-1 Source : http://perso.club-internet.fr/alfosse/cinfo.htm Nouvelle adresse : http://listoiseauxmonde.multimania. -

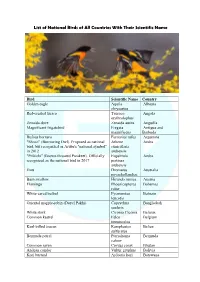

List of National Birds of All Countries with Their Scientific Name

List of National Birds of All Countries With Their Scientific Name Bird Scientific Name Country Golden eagle Aquila Albania chrysaetos Red-crested turaco Tauraco Angola erythrolophus Zenaida dove Zenaida aurita Anguilla Magnificent frigatebird Fregata Antigua and magnificens Barbuda Rufous hornero Furnarius rufus Argentina "Shoco" (Burrowing Owl). Proposed as national Athene Aruba bird, but recognized as Aruba's "national symbol" cunicularia in 2012 arubensis "Prikichi" (Brown-throated Parakeet). Officially Eupsittula Aruba recognized as the national bird in 2017 pertinax arubensis Emu Dromaius Australia novaehollandiae Barn swallow Hirundo rustica Austria Flamingo Phoenicopterus Bahamas ruber White-eared bulbul Pycnonotus Bahrain leucotis Oriental magpie-robin (Doyel Pakhi) Copsychus Bangladesh saularis White stork Ciconia Ciconia Belarus Common kestrel Falco Belgium tinnunculus Keel-billed toucan Ramphastos Belize sulfuratus Bermuda petrel Pterodroma Bermuda cahow Common raven Corvus corax Bhutan Andean condor Vultur gryphus Bolivia Kori bustard Ardeotis kori Botswana Rufous-bellied thrush Turdus Brazil rufiventris Mourning dove Zenaida British Virgin macroura Islands Giant ibis Thaumatibis Cambodia gigantea Canada jay Perisoreus Canada canadensis Grand Cayman parrot Amazona Cayman Islands leucocephala caymanensis Andean condor Vultur gryphus Chile Red-crowned crane Grus japonensis China Andean condor Vultur gryphus Colombia Clay-colored thrush Turdus grayi Costa Rica Common nightingale Luscinia Croatia megarhynchos Cuban trogon Priotelus -

Acoustic Behavior and Ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus Mocinno, a Flagship Tropical Bird Species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler

Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler To cite this version: Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler. Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species. Biodiversity and Ecology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2019. English. NNT : 2019MNHN0001. tel-02048769 HAL Id: tel-02048769 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02048769 Submitted on 25 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2019 N°attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : écologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Pablo BOLAÑOS Le 18 janvier 2019 Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Sous la direction de : Dr. Jérôme SUEUR, Maître de Conférences, MNHN Dr. Thierry AUBIN, Directeur de Recherche, Université Paris Saclay JURY: Dr. Márquez, Rafael Senior Researcher, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid Rapporteur Dr. -

A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell's Thrush

A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) July 2010 International Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group A Conservation Action Plan for Bicknell’s Thrush (Catharus bicknelli) Editors: John Lloyd, Ecostudies Institute Scott Makepeace, Julie A. Hart New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources Christopher C. Rimmer Kent McFarland, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Randy Dettmers Mark McGarrigle, Rebecca M. Whittam New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources Emily A. McKinnon Emily A. McKinnon, York University Kent P. McFarland David Mehlman, The Nature Conservancy Members of the International Brian Mitchell, U.S. National Park Service Bicknell’s Thrush Conservation Group: Robert Ortiz Alexander, Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Santo Domingo Hubert Askanas, University of New Brunswick John Ozard, Yves Aubry, Canadian Wildlife Service / New York Department of Environmental Conservation Service Canadien de la Faune Julie Paquet, Canadian Wildlife Service / Philippe Bayard, Société Audubon Haiti Service Canadien de la Faune James Bridgland, Parks Canada / Parcs Canada Leighlan Prout, USDA Forest Service Jorge Brocca, Sociedad Ornitología de la Hispaniola Joe Racette, Frédéric Bussière, Regroupement QuébecOiseaux New York Department of Environmental Conservation Greg Campbell, Bird Studies Canada / Chris Rimmer, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Études d’Oiseaux Canada Frank Rivera, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ted Cheskey, Nature Canada Carla Sbert, Nature Canada Andrew Coughlan, Bird Studies Canada/ Judith Scarl, Vermont Center for Ecostudies Études d’Oiseaux Canada Henning Stabins, Plum Creek Timber Company William DeLuca, University of Massachusetts Jason Townsend, State University of New York College of Randy Dettmers, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Environmental Science and Forestry Antony W. Diamond, University of New Brunswick Tony Vanbuskirk, Fornebu Lumber Company Andrea Doucette, NewPage Port Hawkesbury Corp Rebecca M.