Skelmorlie Aisle Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scheduled Ancient Monuments List

List of Scheduled Ancient Monuments North Ayrshire (excluding Arran) PARISH MONUMENT Ardrossan : Ardrossan Castle Boydstone Braes, motte Montfode Burn, motte Montfode Castle Beith : Cuffhill Plantation, long cairn Dalry : Aitnock, dun, Hindog Glen Fairlie : Castle Hill, earthwork SSE of Glenside. Fairlie Castle. Southannan Mansionhouse. Irvine : Seagate Castle. Lawthorn Mount, mound. Kilbirnie : Glengarnock Castle Kilwinning : Kilwinning Abbey Waggonway and bridge, SE of Saugh Trees Clonbeith Castle Largs : Castle Hill, fort. Hailie House, chambered cairn. Knock Jargon, cairn and fort. Knock, fort. Outerwards, Roman fortlet. Skelmorlie Aisle and Largs Old Parish Church. Little Cumbrae : Little Cumbrae Castle. Little Cumbrae, lighthouse tower and associated buildings. PARISH MONUMENT Portencross : Auld Hill, fort. Portencross Castle. West Kilbride : Blackshaw Quarry, cup and ring marked rock, 320m south of. Bushglen Mount, ENE of Bushglen. Castle Knowe, motte Stevenston : Ardeer Recreation Club, subterranean passage and cave. Kerelaw Castle Listed of Scheduled Ancient Monuments Isle of Arran Grid Ref. MONUMENT Prehistoric Ritual and Funerary 4433 69 NR978250 Aucheleffan, stone setting 550 NW of 393 69 NR890363 Auchencar, standing stone 90023 69 NR892346 * Auchengallon, cairn, 150m WSW of. 4601 69 NS044237 Bealach Gaothar, ring cairn 700m NW of Largybeg 4425 69 NR924322- Bridge Farm, stone settings 500m NNW and 1040m NW of 69 NR919325 90051 69 NR990262 * Carn Ban, chambered cairn 5962 69 NR884309 Caves, S. of King's Cave. 395 69 NR949211 Clachaig, chambered cairn 396 69 NS026330 Dunan Beag, long cairn and standing stone, Lamlash 397 69 NS 028331 Dunan Mor, chambered cairn, Lamlash 3254 69 NR993207 East Bennan, long cairn 4903 69 NS018355 East Mayish, standing stone 100m ESE of 4840 69 NS006374- Estate Office, standing stones 500m NE of 69 NS007374 398 69 NS0422446 Giant’s Graves, long cairn, Whiting Bay 90186 69 NR904261- Kilpatrick, dun, enclosure, hut circles, cairn and field system 69 NR908264 1km S of. -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Initial Template

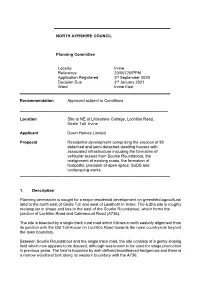

NORTH AYRSHIRE COUNCIL Planning Committee Locality Irvine Reference 20/00725/PPM Application Registered 3rd September 2020 Decision Due 3rd January 2021 Ward Irvine East Recommendation Approved subject to Conditions __________________________________________________________________ Location Site to NE of Littlestane Cottage, Lochlibo Road, Girdle Toll, Irvine Applicant Dawn Homes Limited Proposal Residential development comprising the erection of 92 detached and semi-detached dwelling houses with associated infrastructure including the formation of vehicular access from Sourlie Roundabout, the realignment of existing roads, the formation of footpaths, provision of open space, SuDS and landscaping works ___________________________________________________________________ 1. Description Planning permission is sought for a major residential development on greenfield agricultural land to the north east of Girdle Toll and west of Lawthorn in Irvine. The 6.2ha site is roughly rectangular in shape and lies to the east of the Sourlie Roundabout, which forms the junction of Lochlibo Road and Cairnmount Road (A736). The site is bisected by a single track rural road which follows a north easterly alignment from its junction with the Old Toll House on Lochlibo Road towards the open countryside beyond the town boundary. Between Sourlie Roundabout and the single track road, the site consists of a gently sloping field which now appears to be disused, although was known to be used for silage production in previous years. The field is bounded by well-defined broadleaved hedgerows and there is a narrow woodland belt along its western boundary with the A736. To the east of the single track road is a well-maintained grass field on sloping ground that is currently used for sheep grazing. -

Irvine Locality Partnership

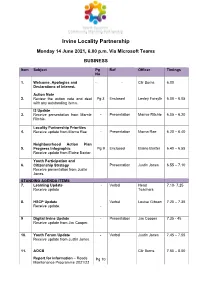

Irvine Locality Partnership Monday 14 June 2021, 6.00 p.m. Via Microsoft Teams BUSINESS Item Subject Pg Ref Officer Timings No 1. Welcome, Apologies and - - Cllr Burns 6.00 Declarations of Interest. Action Note 2. Review the action note and deal Pg 3 Enclosed Lesley Forsyth 6.00 – 6.05 with any outstanding items. I3 Update 3. Receive presentation from Marnie - Presentation Marnie Ritchie 6.05 – 6.20 Ritchie. Locality Partnership Priorities 4. Receive update from Morna Rae - Presentation Morna Rae 6.20 – 6.40 Neighbourhood Action Plan 5. Progress Infographic Pg 9 Enclosed Elaine Baxter 6.40 – 6.55 Receive update from Elaine Baxter. Youth Participation and 6. Citizenship Strategy Presentation Justin Jones 6.55 – 7.10 Receive presentation from Justin Jones. STANDING AGENDA ITEMS 7. Learning Update - Verbal Head 7.10- 7.25 Receive update Teachers 8. HSCP Update Verbal Louise Gibson 7.25 – 7.35 Receive update. - 9 Digital Irvine Update - Presentation Jim Cooper 7.35 - 45 Receive update from Jim Cooper. 10. Youth Forum Update - Verbal Justin Jones 7.45 – 7.55 Receive update from Justin Jones. 11. AOCB Cllr Burns 7.55 – 8.00 Report for information – Roads Pg 10 Maintenance Programme 2021/22 Date of Next Meeting: Monday 27 September 2021 at 6.00 pm via Microsoft Teams Distribution List Elected Members Community Representative Councillor Marie Burns (Chair) Sylvia Mallinson (Vice Chair) Councillor Ian Clarkson Diane Dean (Co- opted) Councillor John Easdale Donna Fitzpatrick Councillor Robert Foster David Mann Councillor Scott Gallacher Peter Marshall Councillor Margaret George Janice Murray Councillor Christina Larsen Annie Small Councillor Shaun Macaulay Ian Wallace Councillor Louise McPhater Councillor Angela Stephen CPP/Council Representatives Lesley Forsyth, Lead Officer Scott McMillan, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service Andy Dolan, Police Scotland Elaine Baxter, Locality Officer Meeting: Irvine Locality Partnership Date/Venue: 15 March 2021 – Virtual Meeting at 6.00 p.m. -

Committee Minutes

Planning Sub Committee of Corporate Services Committee 15 April 2002 IRVINE, 15 April 2002 - At a Meeting of the Planning Sub Committee of Corporate Services Committee at 2.00 p.m Present David Munn, Samuel Gooding, Jack Carson, David Gallagher, Jane Gorman, Elizabeth McLardy, John Moffat, David O'Neill and Robert Rae Also Present James Jennings and Richard Wilkinson In Attendance A Fraser, Principal Legal Officer and D Cartmell, Principal Development Control Officer (Legal and Regulatory); R Forrest, Principal Planner (Development and Promotion); and S Bale and A Sobieraj, Corporate and Democratic Support Officers (Chief Executive's) Chair Councillor Munn in the Chair. Apologies for Absence Elliot Gray, Robert Reilly, Margaret Munn, Elisabethe Marshall and John Sillars. 1. Arran Local Plan Area N/01/00685/OPP: Arran Lochranza: Site to West of Ashbank Mrs Ann Neil, c/o Robert N Brass, Invercloy House, Brodick, Isle of Arran has applied for Outline Planning Permission for a single dwellinghouse at a site to the west of Ashbank, Lochranza, Isle of Arran. An objection has been received from the Arran Civic Trust, 3 Glen Place, Brodick, Isle of Arran. The Sub Committee, having considered the terms of the objection, agreed to grant the application subject to the following conditions: - 1. That the approval of North Ayrshire Council as Planning Authority with regard to the siting, design and external appearance of, landscaping and means of access to the proposed development shall be obtained before the development is commenced. 2. That the first 2 metres of the access, measured from the metalled portion of the A841 fronting the site shall be hard surfaced in order to prevent deleterious material being carried onto the carriageway and designed in such a way that no surface water shall issue from the access onto the carriageway. -

Muniments of the Royal Burgh of Irvine

MUNIMENTS OF THE 1RoK>al JSurcjb of 3rvme VOL. I. DATE MICROFILMED ITEM #__7 PROJECT and G. S. ROLL # CALL # -Hi GENEALOGICAL SC 14/ OF L mi V6|.| PRINTED FOR THE AYRSHIRE AND GALLOWAY ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION MDCCCXC Printed by R. dr= K. Clark FOR DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGH AYRSHIRE AND GALLOWAY AKCH^OLOGICAL ASSOCIATION The EAEL of STAIR, K.T., LL.D., F.P.S.A. Scot., Lord-Lieutenant of Ayrshire and Wigtonshire. The DUKE of PORTLAND. The MARQUESS of BUTE, K.T., LL.D, F.S.A. Scot. The MARQUESS of AILSA. The EARL of EGLINTON and WINTON. The EARL of GALLOWAY, K.T. The EARL of GLASGOW. The LORD HERRIES, Lord-Lieutenant of the Stewartry. The Rt. Hon. Sir JAS. FERGUSSON, Bart,M.P.,G.C.S.I,K.C.M.G.,C I E LL D The Right Hon. Sir J. DALRYMPLE - HAY, Bart, C.B., D C L F ' R S Sir M. SHAW- STEWART, Bart., Lord-Lieutenant of Renfrewshire Sir ANDREW AGNEW, Bart., of Lochnaw. Sir WILLIAM WALLACE, Bart., of Lochryan. Sir WILLIAM J. MONTGOMERY- CUNINGHAME, Bart, Y.C of Corsehill Sir HERBERT EUSTACE MAXWELL, Bart., of Monreith, M.P., F.S.A Scot R A OSWALD, Esq., of Auchincruive. i&on. Secretaries for agrsfnre. R. W. COCHRAN-PATRICK, Esq., of Woodside, LL.D., F.S.A., Hon. Sec. S.A. Scot, Under Secretary for Scotland E H°N HEW - DALRYMPLE, F.S.A. Scot, (for t cJF° Carrick). J. SHEDDEN-DOBIE, Esq., of Morishill, F.S.A. Scot, (for Cuningliame) R. MUNRO, Esq., M.D., M.A., F.S.A Scot. -

National Retailers.Xlsx

THE NATIONAL / SUNDAY NATIONAL RETAILERS Store Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Post Code M&S ABERDEEN E51 2-28 ST. NICHOLAS STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1BU WHS ST NICHOLAS E48 UNIT E5, ST. NICHOLAS CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW SAINSBURYS E55 UNIT 1 ST NICHOLAS CEN SHOPPING CENTRE ABERDEEN AB10 1HW RSMCCOLL130UNIONE53 130 UNION STREET ABERDEEN, GRAMPIAN AB10 1JJ COOP 204UNION E54 204 UNION STREET X ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY CONV E54 SOFA WORKSHOP 206 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1QS SAINSBURY ALF PL E54 492-494 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1TJ TESCO DYCE EXP E44 35 VICTORIA STREET ABERDEEN AB10 1UU TESCO HOLBURN ST E54 207 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BL THISTLE NEWS E54 32 HOLBURN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6BT J&C LYNCH E54 66 BROOMHILL ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6HT COOP GT WEST RD E46 485 GREAT WESTERN ROAD X ABERDEEN AB10 6NN TESCO GT WEST RD E46 571 GREAT WESTERN ROAD ABERDEEN AB10 6PA CJ LANG ST SWITIN E53 43 ST. SWITHIN STREET ABERDEEN AB10 6XL GARTHDEE STORE 19-25 RAMSAY CRESCENT GARTHDEE ABERDEEN AB10 7BL SAINSBURY PFS E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA ASDA BRIDGE OF DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA SAINSBURY G/DEE E55 GARTHDEE ROAD BRIDGE OF DEE ABERDEEN AB10 7QA COSTCUTTER 37 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BN RS MCCOLL 17UNION E53 17 UNION STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5BU ASDA ABERDEEN BEACH E55 UNIT 11 BEACH BOULEVARD RETAIL PARK LINKS ROAD, ABERDEEN AB11 5EJ M & S UNION SQUARE E51 UNION SQUARE 2&3 SOUTH TERRACE ABERDEEN AB11 5PF SUNNYS E55 36-40 MARKET STREET ABERDEEN AB11 5PL TESCO UNION ST E54 499-501 -

COVID-19 Update for Communities 15 May 2020

COVID-19 Update for Communities 15 May 2020 North Coast and Cumbraes Please contact the North Ayrshire Community Planning Team for sharing good ideas for community support during this time. The Team can be contacted by emailing: [email protected] North Coast Our contact centre number is 01294 310000 (Monday to Friday during office hours). They can offer you advice and make referrals to other services. If you want to get in touch with your local Community Support Hub please use the numbers below. This might be for help with accessing food, prescription delivery or for local community groups. The minimum opening hours for the hub phonelines are 10.00 am to 1.00 pm Monday to Friday North Coast Community Hub Contact Details: 07907876444 01475 673309 Doctor’s Surgeries & Out of Hours Largs Medical Group Skelmorlie Surgery West Kilbride Medical Tel: 01475 674545 Tel: 01475 520248 Practice Tel: 01294 823607 Cumbrae Medical Practice Out of Hours Social Services Out of Hours GP Tel: 01475 531 400 Tel: 0800 328 7758 Tel: 111 Social Media Groups Being West Kilbride West Kilbride People Largs People https://en- https://en- https://www.facebook.co gb.facebook.com/grou gb.facebook.com/groups/5 m/groups/1439440952936 ps/WestKilbride/?ref=d 63648587155921/ 838/ irect We know Skelmorlie Fairlie Ayrshire Safer Fairlie Well https://www.facebook.com https://m.facebook.com/Saf https://www.facebook. /groups/576946825650066/ er-Fairlie- com/groups/Skelmorli 106472864317984/ e/ Millport Support Group West Kilbride Villagers https://www.facebook. https://www.facebook.c com/groups/millportsu om/groups/1303048669 pportgroup/ 843759 • Updated Pharmacy Opening Hours available at pg 4 • The Community Hub has a stock of sanitary products. -

The Edinburgh Gazette, November 24, 1908. 1273

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 24, 1908. 1273 and following the bends thereof, to a point Road to Auchengarth ; and the unnamed on the high-water mark, directly opposite road leading from St. Fillan's Road to to a point at which the eastmost side of Millrig. the public highway from Greenock to Largs (b) Railway. joins the south side of the road leading to The Caledonian Railway (Glasgow (Central) the site of St. Fillan's Chapel, marked No. to Wemyss Bay Branch). 388 on Sheet 1.15 of the 25-inch Ordnance 4. The names of the streets in which it is Map of Ayrshire (First Editon, 1856) proposed that electric lines should be laid down proceeding thence due east in a straight within such period not exceeding four years a's line for a distance of 1633 yards or there- may be specified by the Order are as follows :— abouts proceeding thence in a straight That part of the public highway known as line in a northward direction for a distance Kelly Bridge Road from the Kelly Bridge to a of 5 miles 733 yards or thereabouts to point on said road opposite Annat House; the the eastmost boundary wall of the Farm footpath leading from the Kelly Bridge Road Steading called Bogside proceeding thence to Montgomery Terrace ; Montgomery Terrace in a straight line in a north-easterly from Morland Road to its junction with Eglintoii direction for a distance of 1133 yards or Terrace; Morland Road from Montgomery thereabouts to the eastmost corner of the Terrace to its junction with Skelmorlie Castle boundary wall of the Farm Steading Road ; Eglinton Terrace from its junction with called Bankfoot proceeding thence north- Montgomery Terrace to a point opposite Salem west in a straight line for a distance of House ; Crescent Road from its junction with 1 mile 1533 yards or thereabouts to and Eglinton Terrace and Montgomery Terrace terminating at the point of commence- to a point on that road opposite to the before- ment above described. -

Vision 2019 Updating You on the Greyfriars Community

Vision 2019 Updating you on the Greyfriars Community Welcome/Fáilte! It has been two years since the Greyfriars Review was first published. Much has been happening in the Greyfriars community and therefore there is a lot to report! ‘Vision 2019’ aims to give you an update on what we have been doing and to outline future plans. Worship, the arts and community outreach are centered at our three locations – Greyfriars Kirk (GK), the Grassmarket Community Project (GCP) and the Greyfriars Charteris Centre (GCC). They are managed independently, but key members are common to all three organisations so the Greyfriars ethos and ideals are maintained. With enlarged teams, we are taking on more work and responsibilities within the parish and wider community. As with any organisation we are very dependent on our dedicated members, congregation, volunteers and staff to make things happen and are therefore very grateful to them all. We welcome new faces to be part of our community and if you would like to get involved, we will find a place for you. GREYFRIARS TEAM Rev Dr Richard Frazer Steve Lister Minister, Greyfriars Kirk Operations Manager, Greyfriars Kirk [email protected] [email protected] Rev Ken Luscombe Jonny Kinross Associate Minister, Greyfriars Kirk CEO, Grassmarket Community Project [email protected] [email protected] Jo Elliot Session Clerk, Greyfriars Kirk Daniel Fisher Manager, Greyfriars Charteris Centre [email protected] [email protected] Dan Rous Development Manager, Greyfriars Charteris Centre [email protected] 1 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS Greyfriars Kirk (GFK) • Established the University Campus Ministry based at the Greyfriars Charteris Centre. • Grown our congregation with new and contributing members. -

Planning Committee 16 January 2006

Planning Committee 16 January 2006 IRVINE, 16 January 2006 - At a Meeting of the Planning Committee of North Ayrshire Council at 2.00 p.m. Present David Munn, John Moffat, Ian Clarkson, Margie Currie, Stewart Dewar, Elizabeth McLardy, Elisabethe Marshall, Margaret Munn, Alan Munro, David O'Neill, Robert Rae, Donald Reid, John Reid and Ian Richardson. In Attendance A. Fraser, Manager, Legal Services, J. Miller, Chief Development Control Officer and M. Lee, Senior Development Control Officer (Legal and Protective); R. Forrest, Planning Services Manager and R. McAlindin, Planning Officer (Development and Promotion); A. Wattie, Communications and M. Anderson, Corporate and Democratic Support Officer (Chief Executive's). Chair Councillor D. Munn in the Chair. Apologies for Absence Tom Barr. 1. Minutes The Minutes of the Meetings of the Committee held on (i) 14 November; and (ii) 5 December 2005, copies of which had previously been circulated, were confirmed. A. ITEMS REQUIRING APPROVAL BY COUNCIL 2. Conservation Areas: West Kilbride and Skelmorlie The Committee received a presentation from Gordon Fleming of Consultants ARP Lorimer and Associates on the factors taken into account in considering the proposed West Kilbride Conservation Area and the extension of the Skelmorlie Conservation Area, including the re-examination of Tree Preservation Orders. Mr. Fleming gave examples of a number of considerations, such as the quality and historical interest of the built environment, as well as the character of streets and boundary treatments. Page 1 Mr. Fleming circulated summary documents on the Conservation Area assessment for West Kilbride and the Conservation Area appraisal for Skelmorlie and Upper Skelmorlie. Noted. -

Greyfriars Bobby Differentiated Reading

Greyfriars Bobby John Gray, known as Jock, lived in Edinburgh around 1850. He was a nightwatchman with the Edinburgh City Police. Jock had a little Skye Terrier to keep him company as he went on his rounds through the streets at night. He called his watchdog Bobby. Jock became ill and died on the 15th February, 1858. He was buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard in Edinburgh. People living near the Kirkyard saw that Bobby refused to leave his master’s grave. The keeper of Greyfriars tried on many occasions to send Bobby away. In the end, he gave up and, it is said, he made a shelter for Bobby at the side of Jock’s grave. The story of the faithful dog spread throughout Edinburgh. It is reported that every day, people would gather at the Kirkyard waiting for Bobby to leave the grave and go to the same inn that he had gone to with his master, where he was given something to eat. In 1867, a new law was passed that said all dogs should be licensed in the city or they would be destroyed. The Lord Provost of Edinburgh decided to pay for Bobby’s licence and presented him with a collar. The collar can be seen today at the Museum of Edinburgh alongside Bobby’s feeding bowl. The people of Edinburgh took good care of Bobby, but still he remained loyal to his master. For fourteen years, this faithful dog kept watch and guard over his master’s grave until he himself died in 1872. Bobby was buried close to his master in Greyfriars Kirkyard and his headstone reads Greyfriars Bobby - died 14th January 1872 - aged 16 years - Let his loyalty and devotion be a lesson to us all.