Executive Succession, Organizational Performance, and Charisma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PIECES! Build

-.7 WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER S, I960 PAGE TWENTY-POUE ' t ':^ Avcraxe Daily Net Prcee Ron lEwpntng Ijgralb For Use Week Ended Tbe 'Waotlipr' * Oct. 1, ISM < ForMu^ef'0. Wmom Wmmm; A 13 23 /-shefwers Mdlna Senigit, ctmr"' , i tag, eooler. l.ew la SSe. IfiHnj Bfember ef the Andlt bdr. eeder. Htgi dS tn tf. Bnrena e< dnalnttea. M anche$ter^4 City of VUlage Charm VOL. LXXX NO. 5 (TWENTY PAGES) ■ MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 6, 1960 (Claaeltled AdTerttotaf <»> Page 18) PRICE FIVE CENTS State News Roundup Build 3-1 After Four Judge Blocks PittsbUrifh, Oct. 6 (/F)—^Thefend Rlchardeon. Rlcherdeon teeied Death Injury New York Yankees scored two out Nelson. No runs, one hit, no errc^i, one Bridgeport, Oct. 6 (JP)— runs in the third innins and left. U. S.^ Soviet Peace another in the fourth and held NEW YCNRK SBOOND Judge Thomas E. Troland in a S to 1 lead over the Pitts Berra rolled out. Nelson to Superior Court -today denied a burgh Pirates after four in Friend, covering first. Skowron motion for the appointment of struck out on a fast ball. Howard a one-man grand jury and a nings of the second game of looked at a third strike. ' thfc World Series. The Pirates No runs, no hits, no errors, none special states’ attorrtey to re Summit Talks 'I scored their run in the fourth. left. open an investigation into the Red Bloc NEW YORK FIRST PirrSBtTROH SECOND death of 4-year-old Albert Kubek, on a 2-1 count looped a Cimoli walked on a full count. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Spring-2012.Pdf

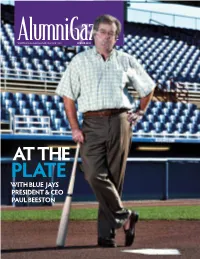

AlumniGazetteWESTERn’S ALUMNI MaGAZINE SINCE 1939 SPRING 2012 AT THE PL ATE WITH BLUE JAYS PRESIDENT & CEO PAUL BEESTON Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing? AlumniGazette Buying?Buying?Buying?Buying? Renewing?Renewing?Renewing?Renewing? Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing?Refinancing? CONTENTS ‘EVERY DAY IS SATURDAY’ 10 Cover story: At the plate with Blue Jays president & CEO Paul Beeston, BA’67, LLD’94 A DIPLOMAT FINDS HER 14 CALLING Sheila Siwela, BA’79, Zambia’s ambassador to the United States THE RIVER RUNS DEEP 16 Valiya Hamza, PhD’73, discovers underground river in Brazil THE WILL TO WIN 18 Silken Laumann, BA’89, reflects on her bronze medal win at the ’92 Olympics NEVER SaY NEVER 20 Tim Hudak, BA’90, and his path to Queen's Park 22 ROCK STAR CommittedCommitted to to Saving Saving YouYou ThousandsThousands Richard Léveillé, PhD’01, and NASA’s Mars CommittedCommittedCommitted to toto Saving SavingSaving You YouYou Thousands ThousandsThousands mission ofof Dollars Dollars on on Your Your NextNext MortgageMortgage ofofof Dollars DollarsDollars on onon Your YourYour Next NextNext Mortgage MortgageMortgage THE CIRQUE LIFE Alumni of Western University can SAVE on a mortgage 26 Craig Cohon, BA’85, brings Cirque du Soleil AlumniAlumniAlumni of of ofWestern Western Western UniversityUniversity University can can SAVE SAVE on onon a aa mortgage mortgagemortgage to Russia withAlumni the of best Western available University rates in can Canada SAVE while on a enjoyingmortgage withwithwith the the the best best best available available available ratesrates rates in in Canada Canada whilewhile while enjoying enjoyingenjoying outstandingwith the best service. available Whether rates in purchasing Canada while your enjoying first 20 outstandingoutstandingoutstanding service. -

2007 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser

2007 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser Saturday, January 13, 2007 Dress - Business Casual 6:00 - 10:30 p.m. Contact: Northern Lights Ballroom Greg Hamilton Renaissance Toronto Downtown Head Coach & Director, (Rogers Centre) National Teams Program 3:30 p.m. Press Conference (Aurora Room) 9:00 p.m. Award Presentations & Videos 6:00 p.m. Cocktail Hour Emcee: Jerry Howarth, Toronto Blue Jays 7:45 p.m. Dinner 10:30 p.m. Auction & Autographs Award Winners Brett Lawrie Ernie Whitt Junior Team MVP Toronto Blue Jays & WBC Presented by Disney’s Special Recognition Award Wide World of Sports Mike Saunders Adam Stern Seattle Mariners Baltimore Orioles & WBC Senior National Team MVP Stubby Clapp Award Presented by Mizuno Jason Dickson Eric Gagne Canadian Olympic Team Texas Rangers Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Achievement Award Presented by MLB Players Association Russell Martin Justin Morneau Los Angeles Dodgers Minnesota Twins Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Achievement Award Presented by MLB Players Association Terry Puhl Houston Astros & Cdn Olympic Team Special Recognition Award Alumni Auction Silent Auction Including MLB and National Team Autographed Items MLB Alumni & Friends (Additional Alumni & Friends listed on www.baseball.ca) Paul Quantrill World Baseball Classic Al Schlazer Disney’s Wide World of Sports Jeff Francis Colorado Rockies Rob Ducey 2004 Olympic Team Adam Loewen Baltimore Orioles Pierre-Luc Laforest San Diego Padres Peter Orr Atlanta Braves Chris Robinson Chicago Cubs Scott Thorman Atlanta Braves Nick Weglarz Cleveland Indians Jamie Romak Atlanta Braves Paul Beeston Former C.O.O. MLB & Blue Jays Paul Godfrey Toronto Blue Jays Steve Rogers Montreal Expos & MLB Players Assoc. -

2015 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser

2015 Baseball Canada National Teams Awards Banquet & Fundraiser Saturday January 10th, 2015 Northern Lights Ballroom Renaissance Toronto Downtown (Rogers Centre) Program 3:30 p.m. Press Conference (Aurora Room) 9:15 p.m. Award Presentations & Videos 6:00 p.m. Cocktail Hour 10:45 p.m. Autographs 7:45 p.m. Dinner Emcee: Mike Wilner, Sportsnet - 590 The Fan Award Winners Gareth Morgan Josh Naylor Seattle Mariners Junior National Team Junior National Team MVP Canadian Futures Award Presented by ESPN Wide World of Sports Presented by The Toronto Chapter of BBWAA Justin Morneau Jamie Romak Colorado Rockies Los Angeles Dodgers Stubby Clapp Award Special Achievement Award Presented by Mizuno Canada Presented by MLB Players Association Jeff Francis Roberto Alomar Toronto Blue Jays Toronto Blue Jays Baseball Canada Alumni Award Special Recognition Award Presented by L.J. Pearson Foundation Presented by MLB Players Association Russell Martin Toronto Blue Jays Wall of Excellence Presented by RBC Wealth Management Alumni Auction • Live & Silent Auction Including MLB and National Team Autographed Items • Ryan Dempster Cubs Fantasy Package For Four People – Spend A Day with Ryan ( 3 Game Series at Wrigley, 3 Nights Hotel, 2 Dinners - Clubhouse, Scoreboard & Broadcast Booth Tours with Ryan, On field Batting Practice with Ryan, Lunch & Dinner with Ryan ) MLB Alumni & Friends (Additional Alumni & Friends listed on www.baseball.ca) ! Larry Walker St. Louis Cardinals & WBC ! Joey Votto Cincinnati Reds & WBC ! John Axford Pittsburgh Pirates & WBC ! Mike Saunders -

Cubs 2013 Preview: a Bit Better Pitching, but Rebuilding Still Grinds Along Slowly

Cubs 2013 preview: A bit better pitching, but rebuilding still grinds along slowly By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Friday, March 29, 2013 Theo Epstein is getting double for his money these days. First, the former lifelong Bostonian is getting a valuable education in Chicago politics as the three- cornered debate over Wrigley Field renovations shows how Clout City USA really works. And yet all the arguments over whether the Cubs should get seri- ous with Rosemont and consider moving if they don’t get a renova- Cubs GM Jed Hoyer (with wife Merrill) and boss Theo Ep- tions deal very soon give Epstein stein have once again constructed a roster that can be and his baseball operations depart- disassembled via mid-season trades. ment a big break. Off-the-field issues involving Wrigley Field, whether the installation of lights, falling concrete or Arne Harris’ hat shots, are always far more than sideshows. They become the main story, relegating the Cubs’ on-field fortunes to notebook status. The taffy pull involving Tom Ricketts, Rahm Emanuel, Tom Tunney, the rooftop owners and the vil- lage of Rosemont absolutely shifted the Cubs’ spring-training countdown to Opening Day to secondary news-angle status. If all focus was on the team itself, the conclusion would be a sub-standard roster with a slew of place-holders that is being intentionally fielded for the second-year in a row. Worse yet, as Epstein vows a rebuilding-from-the-ground-up strategy, there are no pitching phenoms or fresh-faced hot rookies as attention-getters to make the continual losing more palatable. -

TMTORONTO BLUE JAYS and All Related Marks and Designs Are Trademarks And/Or Copyright of Rogers Blue Jays Baseball Partnership

FAN PACK TMTORONTO BLUE JAYS and all related marks and designs are trademarks and/or copyright of Rogers Blue Jays Baseball Partnership. ©2020 2020 SEASON SCHEDULE MARCH/APRIL MAY SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 26 27 28 1 2 BOS BOS BOS NYY NYY 3:37PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BOS CIN CIN CIN NYY NYY NYY BAL BAL BAL OAK OAK 1:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 4:07PM 1:05PM 1:05PM 1:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 12:37PM 10:07PM 9:07PM 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 NYY PHI PHI KC KC KC OAK TEX TEX TEX CWS CWS CWS 1:05PM 7:05PM 7:05PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 4:07PM 8:05PM 8:05PM 8:05PM 8:10PM 8:10PM 7:10PM 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 KC MIN MIN MIN TB TB CWS HOU HOU HOU BAL BAL BAL 1:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:10PM 6:10PM 2:10PM 4:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 19 TB 20 21 BOS 22 BOS 23 BOS 24 25 24 BAL 25 26 27 28 29 30 1:10PM 7:10PM 7:10PM 7:10PM 1:07PM 26 BAL 27 BOS 28 BOS 29 BOS 30 BAL BAL 31 BAL TB TB TB BAL BAL 1:05PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:05PM 4:05PM 1:05PM 7:10PM 7:10PM 1:10PM 7:05PM 4:05PM JUNE JULY SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 STL STL TEX TEX TEX CWS CWS NYY NYY 8:15PM 8:15PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 1:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 3:07PM 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 TEX SEA SEA SEA DET DET NYY BOS BOS BOS MIN MIN MIN 1:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 12:37PM 7:10PM 4:10PM 1:07PM 7:10PM 7:10PM 7:10PM 8:10PM 8:10PM 2:10PM 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 DET TB TB TB PIT PIT MIN ALL-STAR BREAK CLE CLE 1:10PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:07PM 7:05PM 4:05PM -

Former Hostage to Speak at ND by SEAN S

ACCENT: Holy Cross Associates in Chile Balmy Mostly sunny, high in the mid VIEWPOINT: Don’t overlook poverty 70s. JEJ T h e O b s e r v e r ___________________ VOL . XXI, NO. 43 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1987 the independent newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's Former hostage to speak at ND By SEAN S. HICKEY Damascus, Syria, in Nov. 1984. Staff Reporter “They met with Syrian offi cials, Palestinian ■‘groups and A former Beirut hostage will almost anyone they could find, be speaking tonight at Galvin including representatives of Life Science at 8 in room 283. Syrian prime-minister Assad,” A Beirut bureau chief for the said Gaffney. He added it is un Cable News Network and pres clear whether Levin escaped ently a Woodrow Wilson Fellow because of his own ingenuity or at Princeton University, Jerry his wife’s efforts. Levin was abducted by the Is “The mystery is whether he lamic Jihad on March 7, 1984 escaped or was released in while walking to work in directly,” said Gaffney. “Most Beirut. The militant Shi’ite observers feel that it was spe group held him prisoner for 343 cial that he got away as op days until February 1985. posed to a disguised release. “Notre Dame had a secret Anyway it is clear that Lucille connection in Levin’s escape,” Levin met her husband’s cap said Father Patrick Gaffney, tors.” an assistant professor and a Islamic Jihad, a radical Middle East specialist. Shi’ite Muslim group issued a That connection was statement the week after they Landrum Bolling, director of released Levin saying they the Notre Dame Institute of decided to do so because they Ecumenical Studies in Israel, determined he was not a sub who was contacted by Levin’s versive. -

Celebrating 27 Years. “1994-2021” 1 U | MESSAGE

ONTARIO SPORTS HALL OF FAME | Celebrating 27 Years. “1994-2021” 1 u | MESSAGE A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT… 2020 was a year of tremendous upheaval for our province, testing the patience and endurance of our communities as we managed through the covid-19 crisis. The priority for all of us was to focus on mitigating the spread of this virus and keeping our communities safe. To that end, we elected to reschedule our annual celebration one year out at a new venue, the John Bassett Theatre in order to recognize our inductees and special award recipients. Our annual induction ceremony and awards gala is in its’ 27th year and I offer my personal and profound thanks for your past support for our annual celebration and related community activities. This year’s OSHOF Gala will present another stellar “Class of 2021” inductee lineup including an outstanding selection of special award recipients. Whether you choose to come on board as a major partner, as a corporate sponsor or with the purchase of individual tickets for you and your guests, your participation provides invaluable support enabling us to showcase and appreciate our most recognized sports athletes, community leaders and volunteer citizens. Of course, you can expect to indulge in a fabulous evening of tasty hors d’oeuvres, cocktails and unforgettable entertainment and many opportunities to bid on selected treasures in the live auction and participate in our 50-50 raffle. It’s a night of networking with your sporting heroes, business, community and philanthropic leaders, not to mention the athletes themselves. To our board of directors and volunteers who donate their time, talent and creativity, I extend my appreciation to them all! We must rely upon your generosity to sustain our celebration, education and awareness of Ontario sporting accomplishments to our citizens and communities across Ontario. -

Justin Morneau Elected to Minnesota Twins Hall of Fame Morneau Will Become the 34Th Member of the Twins Hall of Fame

TICKETS SCHEDULE SCORES STATS News Twins Press Releases Justin Morneau elected to Minnesota Twins Hall Of Fame Morneau will become the 34th member of the Twins Hall of Fame January 24, 2020 MINNEAPOLIS-ST. PAUL, MN — The Minnesota Twins announced today that former Twins first baseman Justin Morneau has been elected to the club’s Hall of Fame. Morneau will become the 34th member of the Twins Hall of Fame when he is inducted during an on-field pre-game ceremony at Target Field before the Twins host the Chicago White Sox on Saturday, May 23 in a game presented by Sheboygan Sausage Company. The Twins Hall of Fame, which honors players, managers, coaches and off-field personnel who have contributed to the organization’s growth and success since Minnesota broke into the major leagues in 1961, was created as part of the club’s 40th Season Celebration in 2000. The inaugural class of Twins Hall of Famers—Harmon Killebrew, Rod Carew, Tony Oliva, Kent Hrbek, Kirby Puckett and Calvin Griffith — was inducted on August 12, 2000. Other inductees include: pitcher Jim Kaat and broadcaster Herb Carneal (2001); pitcher Bert Blyleven and manager Tom Kelly (2002); long-time public address announcer Bob Casey and outfielder Bob Allison (2003); catcher Earl Battey (2004); pitcher Frank Viola (2005) and owner Carl Pohlad (2005); shortstop Zoilo Versalles (2006); third baseman Gary Gaetti (2007) and farm director Jim Rantz (2007); pitcher Rick Aguilera (2008); pitcher Brad Radke and farm and scouting director George Brophy (2009); shortstop Greg Gagne (2010); pitcher Jim Perry (2011); pitcher Camilo Pascual (2012); pitcher Eddie Guardado and director of media relations Tom Mee (2013); second baseman Chuck Knoblauch was elected in 2014 but not inducted; outfielder Torii Hunter and radio broadcaster John Gordon (2016); outfielder Michael Cuddyer and former general manager Andy MacPhail (2017); pitcher Johan Santana (2018); and, pitcher Joe Nathan and former club president Jerry Bell (2019). -

Front Office Directory Brad Mohr

FRONT OfficE DIRECTORY Brad Mohr ................................................................................................ Manager, Baseball Operations Willie Jenks .................................................................................................Visiting Clubhouse Manager OFFICERS Steve Walters .......................................................................................... Coordinator, Ballpark Services Lawrence J. Dolan ................................................................................ Owner & Chief Executive Officer Gloria Carter ........................................................................................... Assistant, Ballpark Operations Paul J. Dolan ............................................................................................................................ President Kenny Campbell ...................................................................................................Main Lobby Reception Mark Shapiro ...................................................................... Executive Vice President, General Manager Louis Pavlick .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Dennis Lehman ................................................................................Executive Vice President, Business Ray Branham .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Victor Gregovits .................................................................... -

Sox's New Trier Connection Gets Stronger with Tilson, Huff

White Sox's New Trier High connection gets stronger with Charlie Tilson, Mike Huff By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 9, 2017 The White Sox’s historical New Trier High School connection just got a little stronger. His status as the team’s center fielder coming out of camp de- layed due to a stress reaction in his right foot, Wilmette native Charlie Tilson has made friends with a fellow alum of the legendary north suburban school, traditionally rated as Charlie Tilson (left) already has been in contact with fellow one of the best academically in New Trier alum Mike Huff (right), working at a Bulls/Sox Acad- the country. emy clinic with ex-slugger Jim Thome. Former Sox outfielder Mike Huff, vice president of baseball/fastpitch, and bunting and baserunning instructor at the west suburban Lisle-based BullsSox Academy, was New Trier’s representative on the 1993 AL West champion Sox. Since Tilson came into the Sox organization last summer via a trade from the Cardinals, the fellow former Trevians have had “a couple of great conversations.” Then they stayed in touch via e-mail. “Stay true to yourself,” was Huff’s main counsel to Tilson, slowed in Glendale due to a foot injury. If Tilson does win the center-field job, and needs some familiar pick-me-up from Huff, the latter will consider asking the permission of GM Rick Hahn and manager Ricky Renteria for supplement the advice the kid gets from Sox coaches. “I know they’d be 100 percent behind that,” said Huff.