Growth Linkages and Policy Effects in a Village Economy in Ethiopia: an Analysis of Interactions Using a Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

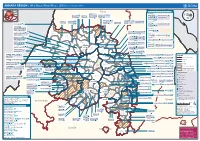

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

ETHIOPIA Ethiopia Is a Federal Republic Led by Prime

ETHIOPIA Ethiopia is a federal republic led by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi and the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The population is estimated at 82 million. In the May national parliamentary elections, the EPRDF and affiliated parties won 545 of 547 seats to remain in power for a fourth consecutive five-year term. In simultaneous elections for regional parliaments, the EPRDF and its affiliates won 1,903 of 1,904 seats. In local and by-elections held in 2008, the EPRDF and its affiliates won all but four of 3.4 million contested seats after the opposition parties, citing electoral mismanagement, removed themselves from the balloting. Although there are more than 90 ostensibly opposition parties, which carried 21 percent of the vote nationwide in May, the EPRDF and its affiliates, in a first-past-the-post electoral system, won more than 99 percent of all seats at all levels. Although the relatively few international officials that were allowed to observe the elections concluded that technical aspects of the vote were handled competently, some also noted that an environment conducive to free and fair elections was not in place prior to election day. Several laws, regulations, and procedures implemented since the 2005 national elections created a clear advantage for the EPRDF throughout the electoral process. Political parties were predominantly ethnically based, and opposition parties remained splintered. During the year fighting between government forces, including local militias, and the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), an ethnically based, violent insurgent movement operating in the Somali region, resulted in continued allegations of human rights abuses by all parties to the conflict. -

World Bank Document

Inv I l i RNE S Tl RI ECTr r LULIPYi~iIriReport No. AF-60a I.1 Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared for use within the Bank and its affiliated orgonizations. TThey do not accept responsibility for itg accuracy or completeness. The report may not be published nor marj it be quoted as representingr their views.' TNTPRNATTCkNL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION-AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT. ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized THE ECONOMY OF ETHIOPIA (in five volumes) Itrf"%T TT'KXL' TTT -V %J..JAULJLV.L;& ".L.L TRANSPORTATION Public Disclosure Authorized August 31, 1967 Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Unit - Ethiopian dollar (Eth$) US$1. 00 Eth$Z.50 T. 1,-.1 nn - TTChn AA METRIC SYSTEM 1 meter (m) = 39. 37 inches 1 kilometer (km) = 0. 62 miles 1 hectare (ha) = 2.471 acres 1 square k4lot-neter = 0.38 square m0iles TIME The Ethiopian calender year (EC) runs from September 11 to September 10. Moreover, there is a difference of about 7-3/4 years between the Gregorian and the Ethiopian era. For intance, 1959 EC runs froM. September 11, 1966 to September 10, 1967. Most of the official Ethiopian statistics on national accounts, production, and foreign trade are converted to the Gregorian calender. Throughout the report the Gregorian calender is used. The Ethiopian budget year begins on July 8. For example, Ethiopian budget year 1959 runs from July 8, 1966 to July 7, 1967. In the report this year is referred to as budget year 1966/67. ECONOMY OF ETHIOPIA VOLUME III TRANSPOITATION This- repointW+. -

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (August 2017)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (August 2017) ERITREA National capital P Erob Tahtay Adiyabo Regional capital Gulomekeda Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Ahferom Red Sea Humera Adigrat ! ! Dalul ! Adwa Ganta Afeshum Aksum Saesie Tsaedaemba Shire Indasilase ! Zonal Capital ! North West TigrayTahtay KoraroTahtay Maychew Eastern Tigray Kafta Humera Laelay Maychew Werei Leke TIGRAY Asgede Tsimbila Central Tigray Hawzen Medebay Zana Koneba Naeder Adet Berahile Region boundary Atsbi Wenberta Western Tigray Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele Zone boundary Tanqua Abergele P Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Tsegede Tselemt Mekele Town Special Enderta Afdera Addi Arekay South East Ab Ala Tsegede Mirab Armacho Beyeda Woreda boundary Debark Erebti SUDAN Hintalo Wejirat Saharti Samre Tach Armacho Abergele Sanja ! Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Addis Ababa Ziquala Maychew ! Wegera Metema Lay Armacho Wag Himra Endamehoni Raya Azebo North Gondar Gonder ! Sekota Teru Afar Chilga Southern Tigray Gonder City Adm. Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Gaz Gibla Zone 4 (Fantana Rasu ) Elidar Amhara Gelegu Quara ! Takusa Ebenat Gulina Bugna Awra Libo Kemkem Kobo Gidan Lasta Benishangul Gumuz North Wello AFAR Alfa Zone 1(Awsi Rasu) Debre Tabor Ewa ! Fogera Farta Lay Gayint Semera Meket Guba Lafto DPubti DJIBOUTI Jawi South Gondar Dire Dawa Semen Achefer East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Delanta Habru Asayita P Tach Gayint ! Bahir Dar City Adm. Aysaita Guba AMHARA Dera Ambasel Debub Achefer Bahirdar Zuria Dawunt Worebabu Gambela Dangura West Esite Gulf of Aden Mecha Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Simada Thehulederie Kutaber Dangila Yilmana Densa Afambo Mekdela Tenta Awi Dessie Bati Hulet Ej Enese ! Hareri Sayint Dessie City Adm. -

Migration and Rural-Urban Linkages in Ethiopia

Migration and Rural-Urban Linkages in Ethiopia: Cases studies of five rural and two urban sites in Addis Ababa, Amhara, Oromia and SNNP Regions and Implications for Policy and Development Practice Prepared for Irish Aid–Ethiopia Final Report Feleke Tadele, Alula Pankhurst, Philippa Bevan and Tom Lavers Research Group on Wellbeing in Developing Countries Ethiopia Programme ESRC WeD Research Programme University of Bath, United Kingdom June 2006 Table of contents 1. Background 1.1. Introduction 1.2. Scope and approaches to the study 1.3. Migration in Ethiopia: an analysis of context 1.4. Theoretical framework 1.4.1. Perspectives on the migration-development nexus 1.4.2. Perspectives on Urban and Rural Settings and Urban-Rural Linkages 1.4.3. Spatial Patterns, Urban-Rural linkages and labour flows in Ethiopia 2. Empirical findings from the WeD research programme and emerging issues 2.1. Reasons for migration 2.1.1. Reasons for in- and out-migration: urban sites 2.1.2. Reasons for in- and out-migration: rural sites 2.2. Type of work and livelihood of migrants 2.2.1. Urban sites 2.2.2. Rural sites 2.3. Spatial patterns, urban-rural linkages and labour flows 2.3.1. Urban sites 2.3.2. Rural sites 2.4. Preferences regarding urban centres and geographic locations 2.5. Diversity of migrants 2.5.1. Age 2.5.2. Education 2.5.3. Gender 2.6. Labour force and employment opportunities 2.7. The role of brokers and management of labour migration 2.8. Barriers and facilitating factors for labour migration 2.9. -

Ethiopia Integrated Agro-Industrial Parks (Scpz) Support Project

Language: English Original: English PROJECT: ETHIOPIA INTEGRATED AGRO-INDUSTRIAL PARKS (SCPZ) SUPPORT PROJECT COUNTRIES: ETHIOPIA ESIA SUMMARY FOR THE 4 PROPOSED IAIPs AND RTCs LOCATED IN SOUTH WEST AMHARA REGION, CENTRAL EASTERN OROMIA REGION, WESTERN TIGRAY REGION AND EASTERN SNNP REGION, ETHIOPIA. Date: July 2018 Team Leader: C. EZEDINMA, Principal Agro Economist AHFR2 Preparation Team E&S Team Members: E.B. KAHUBIRE, Social Development Officer, RDGE4 /SNSC 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) committed to a five-year undertaking, as part of the first Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP I) to build the foundation to launch the Country from a predominantly agrarian economy into industrialization. Among the sectors to which the second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II) gives emphasis is manufacturing and industrialization to provide the basis for economic structural change; and a central element in this strategy for transforming the industry sector is development and expansion of industrial parks and villages around the country. 1.2. The development of Integrated Agro Industrial Parks (IAIPs) and accompanying Rural Transformation Centres (RTCs) forms part of the government-run Industrial Parks Development Corporations (IPDC) strategy to make Ethiopia’s agricultural sector globally competitive. The concept is driven by a holistic approach to develop integrated Agro Commodity Procurement Zones (ACPZs) and IAIPs with state of-the-art infrastructure with backward and forward linkages based on the Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development model. The concept of IAIPs is to integrate various value chain components via the cluster approach. Associated RTCs are to act as collection points for fresh farm feed and agricultural produce to be transported to the IAIPs where the processing, management, and distributing (including export) activities are to take place. -

Ethiopia Page 1 of 26

Ethiopia Page 1 of 26 Ethiopia Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2003 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 25, 2004 Ethiopia continued its transition from a unitary to a federal system of government, under the leadership of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. According to international and local observers, the 2000 national elections generally were free and fair in most areas; however, serious election irregularities occurred in the Southern Region, particularly in Hadiya zone. The Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and affiliated parties won 519 of 548 seats in the federal parliament. EPRDF and affiliated parties also held all regional councils by large majorities. The regional council remained dissolved at year's end, and no dates had been set for new elections. Highly centralized authority, poverty, civil conflict, and limited familiarity with democratic concepts combined to complicate the implementation of federalism. The Government's ability to protect constitutional rights at the local level was limited and uneven. Although political parties predominantly were ethnically based, opposition parties were engaged in a gradual process of consolidation. Local administrative, police, and judicial systems remained weak throughout the country. The judiciary was weak and overburdened but continued to show signs of independence; progress was made in reducing the backlog of cases. The security forces consisted of the military and the police, both of which were responsible for internal security. The Federal Police Commission and the Federal Prisons Administration were subordinate to the Ministry of Federal Affairs. The military, which was responsible for external security, consisted of both air and ground forces and reported to the Ministry of National Defense. -

The Mineral Industry of Ethiopia in 2009

2009 Minerals Yearbook ETHIOPIA U.S. Department of the Interior September 2011 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF ETHIOPIA By Thomas R. Yager In 2009, Ethiopia played a significant role in the world’s Production at Sakaro was likely to be about 2,400 kg/yr from production of tantalum; the country’s share of global tantalum 2012 to 2014 and 1,800 kg/yr from 2015 to 2021. Midroc was mine production amounted to 6% (Papp, 2010). Other also considering the development of the Werseti Mine, which domestically significant mining and mineral processing could open in 2015 and produce nearly 3,500 kg/yr from 2016 operations included cement, crushed stone, dimension stone, to 2021. If all of Midroc’s planned projects were to proceed, the and gold. Ethiopia was not a globally significant consumer of company would produce about 6,000 kg/yr of gold from 2014 to minerals. 2021 (Midroc Gold Mine plc, 2009). In February 2009, Nyota Minerals Ltd. (formerly Dwyka Minerals in the National Economy Resources Ltd.) of Australia acquired the Tulu Kapi and the Yubdo gold projects and the Yubdo platinum mine from Minerva In fiscal year 2007-08 (the latest year for which data were Resources plc of the United Kingdom. In 2010, Nyota planned available), the manufacturing sector accounted for 4% of the to spend $3.6 million on exploration in Ethiopia, including gross domestic product, and mining and quarrying, 0.4%. $2.6 million at Tulu Kapi. The company planned to complete Between 300,000 and 500,000 Ethiopians were estimated to resource estimates for Tulu Kapi and Yubdo in 2010. -

An Enterprise Map of Ethiopia

John Sutton and Nebil Kellow An enterprise map of Ethiopia Discussion paper [or working paper, etc.] Original citation: Sutton, John and Kellow, Nebil (2010) An enterprise map of Ethiopia. International Growth Centre, London, UK. ISBN 9781907994005 This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/36390/ Originally available from International Growth Centre Available in LSE Research Online: May 2011 © 2011 International Growth Centre LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — pagei—#1 i i AN ENTERPRISE MAP OF ETHIOPIA i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page ii — #2 i i i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page iii — #3 i i AN ENTERPRISE MAP OF ETHIOPIA John Sutton and Nebil Kellow i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page iv — #4 i i Copyright © 2010 International Growth Centre Published by the International Growth Centre Published in association with the London Publishing Partnership www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk All Rights -

An Enterprise Map of Ethiopia

i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — pagei—#1 i i AN ENTERPRISE MAP OF ETHIOPIA i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page ii — #2 i i i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page iii — #3 i i AN ENTERPRISE MAP OF ETHIOPIA John Sutton and Nebil Kellow i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — page iv — #4 i i Copyright © 2010 International Growth Centre Published by the International Growth Centre Published in association with the London Publishing Partnership www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-907994-00-5 (pbk.) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This book has been composed in Utopia using TEX Copy-edited and typeset by T&T Productions Ltd, London Cover design: LSE Design Unit Cover photograph courtesy of the Engineering Capacity Building Program (ecbp) i i i i i i “ethiopia” — 2010/11/15 — 14:33 — pagev—#5 i i CONTENTS About the Authors ix Acknowledgements xi Acronyms and Abbreviations xiii 1 Introduction 1 2 Widely Diversified Firms 15 2.1 Profiles of Firms 16 Ahadu, DH GEDA, East African Holdings 2.2 MIDROC Ethiopia 22 MIDROC Technology Group, ELICO, Pharmacure, National Mining Corporation PLC, Agri-Ceft Ethiopia 3 Coffee 33 3.1 Sector Profile 33 3.2 Profiles of Major Firms 39 Moplaco, Great Abyssinia, Robera 4 Oilseeds and Pulses 45 4.1 Sector Profile 45 4.2 Profiles of Major Firms 50 Belayneh Kindie Import Export, Guna Trading House, Kabew Trading, Bajiba, Al-Impex 5 Floriculture 59 5.1 Sector Profile 59 5.2 Profiles of Major Firms 63 AQ Roses, Red -

Tuberculosis Infectious Pool and Associated Factors in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia Mulusew Andualem Asemahagn1* , Getu Degu Alene1 and Solomon Abebe Yimer2,3

Asemahagn et al. BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2019) 19:229 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0995-3 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Tuberculosis infectious pool and associated factors in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia Mulusew Andualem Asemahagn1* , Getu Degu Alene1 and Solomon Abebe Yimer2,3 Abstract Background: Globally, tuberculosis (TB) lasts a major public health concern. Using feasible strategies to estimate TB infectious periods is crucial. The aim of this study was to determine the magnitude of TB infectious period and associated factors in East Gojjam zone. Methods: An institution-based prospective study was conducted among 348 pulmonary TB (PTB) cases between December 2017 and December 2018. TB cases were recruited from all health facilities located in Hulet Eju Enesie, Enebse Sarmider, Debay Tilatgen, Dejen, Debre-Markos town administration, and Machakel districts. Data were collected through an exit interview using a structured questionnaire and analyzed by IBM SPSS version25. The TB infectious period of each patient category was determined using the TB management time and sputum smear conversion time. The sum of the infectious period of each patient category gave the infectious pool of the study area. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with the magnitude of TB infectious period. Results: Of the total participated PTB cases, 209(60%) were male, 226(65%) aged < 30 years, 205(59%) were from the rural settings, and 77 (22%) had comorbidities. The magnitude of the TB infectious pool in the study area was 78,031 infectious person-days. The undiagnosed TB cases (44,895 days), smear-positive (14,625 days) and smear- negative (12,995 days) were major contributors to the infectious pool. -

Pact Inc. in Zambia and Ethiopia the Y-CHOICES Program Annual Report

Pact Inc. in Zambia and Ethiopia The Y-CHOICES Program Cooperative Agreement No. GPO-A-00-04-00024-00 Annual Report October 1, 2005 – September 30, 2006 Submitted: November 8, 2006 Program Duration: October 1, 2004 – September 29, 2009 Table of Contents Acronyms…………………..……………………………………………………………………2 I. Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………..4 Strategic Objectives.....................................................................................................................4 General Overview of Activities and Approaches.........................................................................4 General Summary of Results and Successes ................................................................................5 Coming Six-months Activities.....................................................................................................6 II. Emergency Plan Indicators Tables…………………………………………………………7 Progress on Yearly Targets for Required Emergency Plan Indicators – Zambia and Ethiopia .....7 L.O.A. Progress Tracking Table for Emergency Plan Indicators –Zambia and Ethiopia .............9 III. Country-level Progress Report………………………………………………………..10 Pact Zambia Country Overview................................................................................................10 Pact Ethiopia - Country Overview ............................................................................................16 Ethiopia Y-CHOICES Operational Regions and Implementing Partners ...........................................16 Zambia - Summary of