Nephi's Political Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctrine and Covenants Stories

CHAPTER 15 A Mission to the Lamanites September 1830 esus wanted more people to hear about the gospel. J He wanted some of the Saints to go on missions. He called Oliver Cowdery to go on a mission to the American Indians. These Indians were also called Lamanites because some of them were descended from the Lamanites in the Book of Mormon. Doctrine and Covenants 28:8 Jesus wanted the Lamanites to read the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon tells the Lamanites about their He had promised many prophets that the Lamanites ancestors who lived hundreds of years ago. It tells them would have the Book of Mormon. Now it was time to about important promises Jesus made to them. It helps keep that promise. them believe in Jesus. It teaches them to repent and be Doctrine and Covenants 3:19–20 baptized. Doctrine and Covenants 3:19–20 58 Other men wanted to go with Oliver Cowdery to preach First the missionaries went to some tribes in New York. the gospel to the Lamanites. The Lord said three of the The missionaries gave the people the Book of Mormon, men could go. but only a few of them could read. Then the missionaries went to preach to some Lamanites The missionaries left Ohio and went to a town named in Ohio. These people were happy to hear about the Independence in Jackson County, Missouri. Book of Mormon and learn about their ancestors. 59 There were many Lamanites in Missouri. The missionaries Other people in Missouri did not believe the restored preached the gospel to them and gave them the Book of gospel or the Book of Mormon. -

How Did Seeking a King Get in the Way of Sustaining a Prophet?

KnoWhy # 153 July 28, 2016 Helaman, James Fullmer with Rocky Mountain Landscape, Albert Bierstadt How Did Seeking a King Get in the Way of Sustaining a Prophet? “And now it came to pass that after Helaman and his brethren had appointed priests and teachers over the churches that there arose a dissension among them, and they would not give heed to the words of Helaman and his brethren.” Alma 45:23 The Know At the beginning of Alma 45, Mormon provided a Unfortunately, Helaman’s diligent efforts were promptly 1 special heading summary, sometimes referred to as a rejected by a substantial segment of the people: colophon,2 which reads: “The account of the people of Nephi, and their wars and dissensions, in the days of And now it came to pass that after Helaman and Helaman, according to the record of Helaman, which he his brethren had appointed priests and teachers kept in his days” (Alma 45, chapter heading). Although over the churches that there arose a dissension still in the book of Alma, Mormon’s helpful summary among them, and they would not give heed to reveals that a shift in the source text has taken place and the words of Helaman and his brethren. But they emphasizes that Helaman will unfortunately have to grew proud, being lifted up in their hearts, be- face wars and dissensions during his ministry. cause of their exceedingly great riches; therefore they grew rich in their own eyes, and would not After preparing Helaman as his successor, Alma myste- give heed to their words, to walk uprightly before riously disappeared while journeying toward the land of God. -

Book of Mormon 45 Never Has Man Believed in Me As Thou Hast Ether 1-6 by Lenet Hadley Read

Book of Mormon 45 Never Has Man Believed in Me as Thou Hast Ether 1-6 By Lenet Hadley Read (Here is inspirational background as well as evidences supporting the Book of Mormon) I. The brother of Jared was told, "Never has man believed in me as thou hast." A. Thus he was blessed to see Jesus the Christ. B. Joseph Smith was later similarly blessed, and a result was that through the Book of Mormon he came to know of the Jaredites --- that there had actually been more than one ancient civilization upon the American continents. (Some settlers realized there had been one). C. The Golden Plates revealed to Joseph that the Jaredites lived upon this land shortly after the tower of Babel, 2200 to 2000 B.C. 1. Archaeologists now agree there was a civilization at the time of the Jaredites. In North America scholars have given them the name "Adena," after property where remains were found. D. Joseph learned there were four civilizations including Lehi's people beginning at 600 B.C. 1. Archaeologists now agree that there was a separate, later civilization dated to the same time as Lehi. In North America, they are given the name the “Hopewell,” because evidences of their existence were first discovered upon land of a man named Hopewell. 2. A third civilization, the Mulekites, lived upon this land, arriving in a different area but dated from approximately the same time as Lehi. The Book of Mormon gives internal evidence: after their merger, names suddenly appear whose roots come from Mulek, such as Amulek, Amaleki; Amalekites; Amalickiah; and Amalickiahites (See Book of Mormon Index, p. -

Ziba Peterson: from Missionary to Hanging Sheriff H

ZIBA PETERSON: FROM MISSIONARY TO HANGING SHERIFF H. Dean Garrett As the Church of Christ (LDS Church) moved from hatt and Ziba Peterson, were called to go on this impor- New Yo* to Kirtland and then on to Missouri, some of tant, ground-breaking mission (D&C 32). the early converts remained faithful and continued afIT1- iating with the Church until their death while others fell The Lamanite mission was the Eust longdstance into apostasy and left th: Church One person who fell mission in the Church So important was this mission by the wayside is Ziba Peterson Through studying th: that Oliver Cowdery wrote a statement dated 17 October scant historical records of Peterson's life as an early con- 1830 in which he declared: vert to Mormonism, as a missionaxy to the Lamanites, as a resident of Missouri, and as a sheriff in Hangtown, I, Oliver, being commanded by the Lord God, to go California, we can gain a better understandhg of th: forth unto the Lamanites, to proclaim glad tidings of influences that shaped his life. great joy unto them, by presenting unto them the fullness of th: Gospel, of the only begotten Son of One of the first recorded events of Ziba Peterson's God; and also, to rear up a pillar as a witness where life was his baptism into the Church of Christ in Seneca th: temple of God shall be built, in the glorious new Lake, New York, 18 April 1830, by Oliver Cowdery.1 Jerusalem; and having certain brothers with me, who Not much is lamwn of his life before his baptism No are called of GOD TO ASSIST ME, whose names identifiable sources of his birth, parentage, or his early are Parley, and Peter and Ziba, do &refore most childhood have been discovered. -

Life and Times of Mormon (Pdf)

THE LIFE AND TIMES M O R M O N Creating A Sense of Place Prepared by John Lefgren July 23, 2019 The Life and Times of Mormon From Shim to Cumorah -- AD 321 to AD 385 Year Age Event 321 10 Ammaron visits Mormon and instructs him that in Shim there are sacred records engraved on gold. 322 11 Mormon is carried into the land southward to the land of Zarahemla by his father. 326 15 Mormon is visited by the Lord at the age of fifteen, "and taste[s] and [knows] of the goodness of Jesus" (Mormon 1:15). 327 16 Mormon becomes head of the Nephite armies and leads them in battle against the Lamanites. 331 20 Mormon and his army of 42,000 defeats the Lamanite king, Aaron, and his army of 44,000. 335 24 Mormon goes to the hill called Shim in the land Antum, takes the plates of Nephi, and begins his abridgment of the records. 345 34 Nephites retreat to the land of Jashon, but are driven forth again northward to the land of Shem. 346 35 A Nephite army of 30,000 beats a Lamanite army of 50,000. 350 39 The Nephites make a treaty with the Lamanites and the Gadianton Robbers, giving the Nephites the land northward up "to the narrow passage which led into the land southward", and giving the Lamanites the land southward (Mormon 2:28-9). No battles fought between the Nephites and the Lamanites from AD 350 to AD 360. 360 49 Lamanites again come to battle the Nephites. -

The Witness of the King and Queen Astonished the Specta- Jesus According to His Timing

Published Quarterly by The Book of Mormon Foundation Number 119 • Summer 2006 Now the people which were not Lamanites, were Nephites; nevertheless, they were called Nephites, Jacobites, Josephites, Zoramites, Lamanites, Lemuelites, and Ishmaelites. But I, Jacob, shall not hereafter Sam, the Son distinguish them by these names, but I shall call them Lamanites, that seek to destroy the people of Nephi; and those who are friendly to Nephi, I shall call Nephites, or the people of Nephi, according to the reigns of the kings. (Jacob 1:13-14; see also 4 Nephi 1:40-42; of Lehi Mormon 1:8 RLDS) [Jacob 1:13-14, see also 4 Nephi by Gary Whiting 1:36-38, Mormon 1:8 LDS] he opening pages of the Book of Mormon describe Each of the sons of Lehi had families that developed the faith and struggles of the prophet Lehi as seen into tribes known by the name of the son who fathered them. T through the eyes of his son, Nephi. Nephi describes Thus the tribal names were Lamanites, Lemuelites, Nephites, his family’s departure from Jerusalem and the trial of their long Jacobites and Josephites. Even Zoram (Zoramites) and Ishmael journey to the Promised Land. Through the pages of Nephi’s (Ishmaelites) had their names attached to tribal families. spiritual journey, the family and friends of Lehi are introduced. However, never in the Book of Mormon is a tribe named As the story begins, Lehi has four sons: Laman, Lemuel, Sam after Sam. Why is this? and Nephi. The first introduction of the family is given by Although he is somewhat of a mystery, Sam’s life and faith Nephi shortly after they left the land of Jerusalem. -

"Lamanites" and the Spirit of the Lord

"Lamanites" and the Spirit of the Lord Eugene England EDITORS' NOTE: This issue of DIALOGUE, which was funded by Dora Hartvigsen England and Eugene England Sr., and their children and guest-edited by David J. Whittaker, has been planned as an effort to increase understanding of the history of Mor- mon responses to the "Lamanites" — native peoples of the Americas and Poly- nesia. We have invited Eugene England, Jr., professor of English at BYU, to document his parents' efforts, over a period of forty years, to respond to what he names "the spirit of Lehi" — a focused interest in and effort to help those who are called Lamanites. His essay also reviews the sources and proper present use of that term (too often used with misunderstanding and offense) and the origins and prophesied future of those to whom it has been applied. y parents grew up conditioned toward racial prejudice — as did most Americans, including Mormons, through their generation and into part of mine. But something touched my father in his early life and grew con- stantly in him until he and my mother were moved at mid-life gradually to consecrate most of their life's earnings from then on to help Lamanites. I wish to call what touched them "the spirit of Lehi." It came in its earliest, somewhat vague, form to my father when he left home as a seventeen-year-old, took a job as an apprentice Union Pacific coach painter in Pocatello, Idaho, and — because he was still a farmboy in habits and woke up each morning at five — read the Book of Mormon and The Discourses of Brigham Young in his lonely boarding room. -

The Political Dimension in Nephi's Small Plates

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 4 Article 3 10-1-1987 The Political Dimension in Nephi's Small Plates Noel B. Reynolds Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Reynolds, Noel B. (1987) "The Political Dimension in Nephi's Small Plates," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 27 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol27/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Reynolds: The Political Dimension in Nephi's Small Plates the political dimension in nephis small plates noel B reynolds every people needs to know that its laws and rulers are legitimate and authoritative this is why stories of national origins and city founfoundingssoundingsdings are so important to human societies throughout the world such stories provide explanations of the legitimate origins of their laws and their rulers not untypically such traditions also deal with ambiguous elements of the founding explaining away possibly competing accounts when nephi undertook late in his life to write a third account of the founding events of the lehitelehine colony it appears that he wanted to provide his descendants with a document that would serve this function his small plates systematically defend the nephite -

Moroni's Title of Liberty

ZARAHEMLA REC lssue45 .|989 TheMeanirg Behind November Moroni'sTitle of Liberty by David Lamb \-/ ne of the greatest insights es- gain the advantage. Only by con- it is safeto assumethat Moroni was sential to understanding the scrip- stantly looking to the rod which well versedin the word of God and tures can be found in 2 Nephi 8:9: Moses holds up do the Israelites the usageof types and shadows. In "And all things which have been prevail and become victorious over fact, it is highly possiblethat given of God from the beginning of their adversary. Moroni's idea for the title of liberty the world, unto man, are the typlfy- The key to understanding the was the result of his familiarity with ing of him" (lesus Christ). Simply symbolism in this account is found the Jehovah-Nissiaccount. stated, God has placed a pattern in in verse 15 as Moses builds an altar To understandthe symbolism all things, and all things bear witness to commemorate the event and calls associatedwith the title of liberty, it of JesusChrist that we might not be the altar IEHOVAH-NISSI, which is necessaryto realizethat physical deceived. Time after time, God translated means THE LORD IS MY warfare, as depicted in the scrip- reveals this pattern through the BANNER. The Hebrew word nissi tures, is symbolic of spiritual war- means of types and shadows. This may equally be translated as "stan- fare. Satanand his followers con- use of symbolism reminds us that dard," "ensign," or "pole," as well as stantly seekto attack (makewar Jesusis the only one to whom we are "banner." The insight to be gained against)that which belongsto God, to look for eternal salvation and from this event is that only by contendingfor the very souls of deliverance from death and hell. -

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325 Prepared by the Church Educational System Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Send comments and corrections, including typographic errors, to CES Editing, 50 E. North Temple Street, Floor 8, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-2722 USA. E-mail: <[email protected]> Second edition © 1981, 2001 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 4/02 Table of Contents Preface . vii Section 21 Maps . viii “His Word Ye Shall Receive, As If from Mine Own Mouth” . 43 Introduction The Doctrine and Covenants: Section 22 The Voice of the Lord to All Men . 1 Baptism: A New and Everlasting Covenant . 46 Section 1 The Lord’s Preface: “The Voice Section 23 of Warning”. 3 “Strengthen the Church Continually”. 47 Section 2 Section 24 “The Promises Made to the Fathers” . 6 “Declare My Gospel As with the Voice of a Trump” . 48 Section 3 “The Works and the Designs . of Section 25 God Cannot Be Frustrated” . 9 “An Elect Lady” . 50 Section 4 Section 26 “O Ye That Embark in the Service The Law of Common Consent . 54 of God” . 11 Section 27 Section 5 “When Ye Partake of the Sacrament” . 55 The Testimony of Three Witnesses . 12 Section 28 Section 6 “Thou Shalt Not Command Him Who The Arrival of Oliver Cowdery . 14 Is at Thy Head”. 57 Section 7 Section 29 John the Revelator . 17 Prepare against the Day of Tribulation . 59 Section 8 Section 30 The Spirit of Revelation . -

Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Life Spans of Lehi’S Lineage

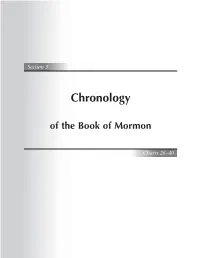

Section 3 Chronology of the Book of Mormon Charts 26–40 Chronology Chart 26 Life Spans of Lehi’s Lineage Key Scripture 1 Nephi–Omni Explanation This chart shows the lineage of Lehi and approximate life spans of him and his descendants, from Nephi to Amaleki, who were re- sponsible for keeping the historical and doctrinal records of their people. Each bar on the chart represents an individual record keeper’s life. Although the Book of Mormon does not give the date of Nephi’s death, it makes good sense to assume that he was approximately seventy-five years old when he died. Source John W. Welch, “Longevity of Book of Mormon People and the ‘Age of Man,’” Journal of Collegium Aesculapium 3 (1985): 34–45. Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Life Spans of Lehi’s Lineage Life span Lehi Life span with unknown date of death Nephi Jacob Enos Jarom Omni Amaron Chemish Abinadom Amaleki 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 YEARS B.C. Charting the Book of Mormon, © 1999 Welch, Welch, FARMS Chart 26 Chronology Chart 27 Life Spans of Mosiah’s Lineage Key Scripture Omni–Alma 27 Explanation Mosiah and his lineage did much to bring people to Jesus Christ. After being instructed by the Lord to lead the people of Nephi out of the land of Nephi, Mosiah preserved their lives and brought to the people of Zarahemla the brass plates and the Nephite records. He also taught the people of Zarahemla the gospel and the lan- guage of the Nephites, and he was made king over both Nephites and Mulekites. -

The Story of the Book of Mormon

The Story of the BOOK OF MORMON 1. The Book of Mormon begins with a prophet named Lehi, who lived with his family in Jerusa- lem. Lehi warned the wicked people in Jerusalem that they would be destroyed if they did not repent, but the people didn’t listen. The Lord told Lehi to take his wife, Sariah, and their sons—Laman, Lemuel, Sam, and Nephi—into the wilder- ness. (See 1 Nephi 1–2.) 3. The Lord gave Lehi a [QUOTE] compass called the Liahona to guide his family through the wilderness to the promised land. “I will go and do (See 1 Nephi 16.) the things which the Lord hath commanded.” 4. The Lord told 5. Lehi and his family 2. After they left their home, Nephi to build a sailed to the promised Lehi sent his sons back to get boat to take his land. (See 1 Nephi 18.) the brass plates. People had father’s family written on them the history to the promised of their ancestors and other land. Nephi things the Lord had told them obeyed his father to write. Lehi and Nephi took and the Lord, but good care of these plates. Laman and Lem- They also wrote on metal uel did not. (See plates what happened to their 1 Nephi 17.) family. (See 1 Nephi 3–5.) 24 Friend 7. After Lehi and Nephi died, other people—such as Nephi’s brother Jacob—were in charge of writing important teach- ings and events on the plates. 6. Laman and Lemuel continued to be disobedient.