Sculpture and the Enemies Issue1 2013.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Art School 2019–2025 Strategic Plan Executive Summary

National Art School 2019–2025 Strategic Plan Executive Summary The National Art School (NAS) sits on one of the most significant sites in Australia – a meeting place for the Gadigal people, the site of the oldest gaol in Australia – and since 1922 the National Art School has called this site home. Over 185 years since our founding, and 96 years on this site, we have had a dynamic history, with many of Australia’s leading artists studying and teaching here. National Art School alumni have framed late 19th Century and 20th Century Australian art practice. They have formed a significant part of the Art Gallery of NSW’s exhibitions and collection acquisitions. One in five Archibald Prize winners has come from the National Art School. But our future is in preparing contemporary artists to be well equipped for the 21st Century. At the leading art fair in the Asia Pacific – the 2018 Sydney Contemporary Art Fair, 56 out of 337 artists were NAS alumni – that is one in 6, more than any other art institution. The National Art School is Australia’s leading independent fine art school; a producer of new art; a place to experience and participate in the arts; and a presentation venue. Our future vision is for a vital and energetic arts and education precinct. A place where art is made, rehearsals take place, art is seen and most importantly people can experience and participate in art. We will partner with other NSW arts organisations to deliver valuable ACDP objectives for the engagement and participation with people living and/or working in regional NSW, people living and/or working in Western Sydney, Aboriginal people, people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds, people with disability, and young people. -

2020 Archibad Prize Media

2020 ARCHIBALD PAUSTRALIA’SRIZ FAVOURITEE PORTRAIT PRIZE 26 SEP 2020 – 10 JAN 2021 ARCHIE FACTS ARCHIBALD, WYNNE & 2020 SULMAN ENTRIES 2565 ARCHIBALD, WYNNE & SULMAN FINALISTS 18 50 181 64 1768 107 53 48 59 396 8 FEMALE MALE 27 ARCHIBALD PRIZE FINALISTS ARCHIBALD PRIZE ENTRIES 55 1068 RECORD YEAR WYNNE PRIZE WYNNE PRIZE FINALISTS 782 ENTRIES 34 SULMAN PRIZE ENTRIES SULMAN PRIZE FINALISTS 715 RECORD YEAR 18 OVER YOUNG ARCHIE ENTRIES FINALISTS YOUNG ARCHIE 40 COMPETITION 1800 FIRST-TIME (40%) ARCHIBALD SMALLEST FINALISTS 22 ARCHIBALD PRIZE ENTRY 25 x 20.5 cm Yuri Shimmyo Carnation, lily, Yuri, rose FIRST-TIME (50%) WYNNE FINALISTS 17 LARGEST FIRST-TIME (33%) ARCHIBALD PRIZE ENTRY SULMAN FINALISTS 6 250 x 250 cm Blak Douglas Writing in the sand NUMBER OF ARTISTS WHO ARE FINALISTS IN MORE THAN ONE PRIZE Abdul Abdullah and Benjamin Aitken (Archibald and Sulman) Lucy Culliton and Guy Maestri (Archibald and Wynne) 6 Caroline Rothwell and Gareth Sansom (Wynne and Sulman) SITTERS IN ARCHIBALD PRIZE ARCHIBALD, WYNNE AND SULMAN PRIZE FINALIST WORKS TOP 3 SUBJECTS WORKS BY INDIGENOUS ARTISTS WORKS BY INDIGENOUS ARTISTS 12 SELF-PORTRAITS 26 RECORD YEAR ARCHIBALD PRIZE WORKS WITH 9 OTHER ARTISTS INDIGENOUS SITTERS 10 RECORD YEAR 8 PERFORMING ARTS Join the conversation #archibaldprize Keep up to date on Facebook, Twitter & Instagram @artgalleryofnsw ANNOUNCEMENTS Announcement of the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prize 2020 finalists; Young Archie finalists and honourable mentions; and Packing Room Prize winner Thursday 17 September, 11am Announcement of the winners of the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2020 Friday 25 September, 12 noon Announcement of winners of the Young Archie 2020 competition Saturday 24 October, 10am ANZ People’s Choice winner announcement Wednesday 16 December, 11am EXHIBITION DATES Archibald, Wynne and Sulman Prizes 2020 Art Gallery of New South Wales Saturday 26 September 2020 – Sunday 10 January 2021 Ticketed Due to COVID-19 capacity restrictions, tickets are $20 adult dated and timed. -

Chapter 4. Australian Art at Auction: the 1960S Market

Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Pedigree and Panache a history of the art auction in australia Shireen huda Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/pedigree_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Author: Huda, Shireen Amber. Title: Pedigree and panache : a history of the art auction in Australia / Shireen Huda. ISBN: 9781921313714 (pbk.) 9781921313721 (web) Notes: Includes index. Bibliography. Subjects: Art auctions--Australia--History. Art--Collectors and collecting--Australia. Art--Prices--Australia. Dewey Number: 702.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: John Webber, A Portrait of Captain James Cook RN, 1782, oil on canvas, 114.3 x 89.7 cm, Collection: National Portrait Gallery, Canberra. Purchased by the Commonwealth Government with the generous assistance of Robert Oatley and John Schaeffer 2000. Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgements -

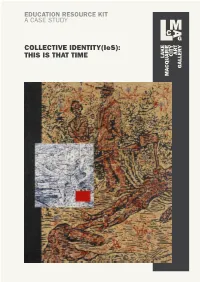

Collective Identity(Ies): This Is That Time

EDUCATION RESOURCE KIT A CASE STUDY COLLECTIVE IDENTITY(IeS): THIS IS THAT TIME 1 INTRODUCTION With the education strategies written by Kate Caddey, the exhibition text prepared by Lisa Corsi and published by Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, this education kit is designed to assist senior secondary Visual Arts teachers and students in the preparation, appreciation and understanding of the case study component of the HSC syllabus. The gallery is proud to support educators and students in the community with an ongoing series of case studies as they relate to the gallery’s exhibition program. This education resource kit is available directly from the gallery, or online at www.artgallery.lakemac.com.au. A CASE STUDY A series of case studies (a minimum of FIVE) should be undertaken with students in the HSC course. The selection of content for the case study should relate various aspects of critical and historical investigations, taking into account practice, the conceptual framework Cover: and the frames. Emphasis may be given to a particular Gordon Bennett aspect of content although all should remain in play. The Nine Ricochets (Fall down black fella, jump up white fella) 1990 Case studies should be 4–10 hours in duration in the oil and synthetic polymer paint HSC course. on canvas and canvas boards 220 x 182cm image courtesy the artist and NSW Board of Studies, Visual Arts Stage 6 Syllabus, 2012 Milani Gallery, Brisbane. photo Carl Warner private collection, Brisbane CONTENTS ABOUT THIS EDUCATION RESOURCE KIT COLLECTIVE IDENTITY(IeS) ESSAY -

Andrew Sibley

Andrew Sibley From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Andrew John Sibley (9 July 1933 – 3 September 2015) was an English-born Australian artist. Sibley has been the subject of three books and is commonly listed in histories and encyclopedias of Australian art as a significant figurative painter of the mid and late 20th century. [1][2][3][4] 1 Personal history 2 Career overviews 2.1 Early career 2.2 Mid-career 2.3 Late career 3 Collections 4 References 5 External links Personal history Sibley was born in Adisham, Kent, England, the first child to John Percival and Marguerite Joan Sibley (née Taylor). With his family home bombed in the London Blitz, Sibley was relocated to Sittingbourne, Kent, then moving to Northfleet, Kent. In 1944 Sibley was awarded a scholarship at Gravesend School of Art, where he studied with fellow students including English artist Peter Blake. [4] In 1948, with his parents and two brothers, Sibley emigrated to Australia, where they lived and worked on an orchard in the rural town of Stanthorpe, Queensland. [5] He left the farm in 1951 to undertake National Service Training with the Royal Australian Navy, after which he spent a short time living and working in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. [6] After meeting his future wife Irena Sibley (née Pauliukonis) in Brisbane in 1967, Sibley followed her to Sydney, where they were married in 1968. The Sibley’s moved to Victoria, where he lived and worked until his death on 3 September 2015 at the age of 82. [7] Career overview From his early success in the 1960s Andrew Sibley consistently exhibited throughout Australia and internationally. -

A Curated Collection of Art to Celebrate Sydney Foreword

ICC Sydney Art Collection A curated collection of art to celebrate Sydney Foreword Built to connect minds, cultures and ideas, International Convention Centre Sydney (ICC Sydney) is the beating heart of Sydney’s new business and events precinct in Darling Harbour. Opened in December 2016, the venue is the centrepiece of a $3.4 billion rejuvenation of the precinct including a major upgrade to the facilities and public domain. Both inside and throughout the public areas, ICC Sydney is home to a superb collection of Australian art. The majority of the collection was commissioned in 1988 during the first major redevelopment of Darling Harbour to commemorate Australia’s bicentennial year and has been added to through the recent rejuvenation. An important part of Sydney’s heritage, the works have a Sydney emphasis with artists and their works initially chosen because of their connection to Sydney or the celebration of Sydney, its harbour and shorelines. There is no more appropriate place than a venue built for gatherings to celebrate the culture of our high performing, multinational, vibrant city, which includes Australia’s Aboriginal heritage. Thanks must go to the artists who donated their works or accepted only a small fee for their generosity. Thanks should also go to ICC Sydney’s venue manager for producing this book to celebrate and share a truly significant piece of Sydney heritage. The Hon. Don Harwin MLC Minister for the Arts 2 3 4 5 Contents 8 Welcome to Country 12 Charles Blackman 48 John Olsen 96 Public Art in 98 Maria Fernanda 122 -

Riparian Life: a Visual Navigation of the Hunter River Estuary

Riparian Life: a visual navigation of the Hunter River Estuary Julianne Tilse Bachelor of Arts - University of Newcastle Master of Arts - University of New South Wales An exegesis submitted in support of creative research for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Fine Art) January 2015 ii Declaration This exegesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University Digital Repository **, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. ** Unless an Embargo has been approved for a determined period. Julianne Tilse January 2015 iii iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the Aboriginal people who were the custodians of the Hunter River for thousands of years prior to the colonization by Europeans. My thanks go to Newcastle University for their support throughout this degree. I acknowledge and thank the many individuals who have supported and encouraged me throughout this study. Dr Angela Philps and Patricia Wilson-Adams for their supervision, insightful feedback, time and professional advice. Nola Farman for her proficient proofreading. My special thanks go to my friends and wider family who have given me their quiet encouragement, inspiration, advice and grounding. Thank you to my creative peers and to my rowing friends who share a passion for the river. -

The Triumph of Landscape Painting • Australian

AUSTRALIAN SURREALISM • THE TRIUMPHTHE LANDSCAPE OF PAINTING artonview ISSUE No.53 autumn 2008 artonview ISSUE No.53 AUTUMN 2007 NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA Z00 31853 Z00 1830s (detail) oil on canvas 35.0 x 44.5 cm Galerie Hans, Hamburg Hans, Galerie cm 44.5 x 35.0 canvas on oil (detail) 1830s h ~ 9 Junenga.gov.au 2008 9 ~ h C Two men observing men moon the Two Caspar David Friedrich David Caspar Canberra only 14 Mar 14 Canberraonly AUSTRALIAN SURREALISM the Agapitos/ Wilson collection A National Gallery of Australia Travelling Exhibition James GLEESON James The attitude of lightning towards a lady-mountain attitude of lightning towards The 1939 oil on canvas Purchased with the assistance of James Agapitos OAM and Ray Wilson OAM, 2007 OAM, Wilson and Ray OAM with the assistance of James Agapitos Purchased 1939 oil on canvas The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government Agency 16 February – 11 May 2008 National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Otto Dix Lens wird mit Bomben belegt [Lens being bombed] etching, drypoint National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Otto Dix, licenced by VISCOPY, Australia 2008 artonview contents Issue 53, autumn 2008 (March–May) published quarterly by National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 2 Director’s foreword nga.gov.au ISSN 1323-4552 5 Foundation and Development Print Post Approved pp255003/00078 8 Turner to Monet: the triumph of landscape © National Gallery of Australia 2008 Copyright for reproductions of artworks is 16 Australian Surrealism: the Agapitos/Wilson collection held by the artists or their estates. Apart from uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of Artonview may be reproduced, 20 Richard Larter: a retrospective transmitted or copied without the prior permission of the National Gallery of Australia. -

TRAVELLING ART SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS 1999–2006 Education Kit

BRETT WHITELEY TRAVELLING ART SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS 1999–2006 Education Kit www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/education Brett Whiteley Studio 15 September – 25 November 2007 BWTAS winners 1999–2006 Education Kit Art Gallery of New South Wales Contents SectiON 1 Brett Whiteley traVelliNG art schOlarshiP: A histOry Brett Whiteley (1939-92) awards, prizes and scholarships: selected biography ‘Young painters meet in Paris’: article by Brett Whiteley Selected references SectiON 2 artists IN PROFile Alice Byrne Marcus Wills Petrea Fellows Ben Quilty Karlee Rawkins Alan Jones Wayde Owen Samuel Wade Questions for consideration: K–6 looking and making activities, 7–12 framing questions EDUCATION KIT OUTLIne This education kit highlights the work of artists who have been awarded the Brett Whiteley Travelling Art Scholarship. As the scholarship is a painting prize, the primary focus for this kit is the contemporary painting practice of young emerging artists. It has been designed to provide a context for looking at previous winning works on display in the exhibition BWTAS winners 1999–2006. The kit has been written with reference to the NSW Visual Arts syllabus as a resource for K–6 and 7–12 education audiences. It may be used in conjunction with a visit to the exhibition or as pre-visit or post-visit resource material. It specifically targets teacher and student audiences but may also be of interest to a general audience. AckNOwleDGMENts Thank you to all the previous winners of the BWTAS for their assistance and support. Beryl Whiteley for her initial vision and generosity to establish the BWTAS, as well as her continued commitment. -

Wendy Stavrianos

NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY WENDY STAVRIANOS 1961 Awarded Diploma of Fine Art, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology 1961-62 Art teacher, Hermitage, Geelong 1963 Overseas study: Greece, Italy, England 1964-69 Art teacher, Coburg Technical College; Emily MacPherson College; MLC Hawthorn; RMIT (painting), part-time 1970 Art teacher, RMIT (print-making) 1971 Art teacher, Caulfield Grammar School 1972 Overseas study, Bali 1973-75 Lecturer Grade I, Darwin Community College 1978-85 Lecturer, Canberra School of Art 1985-87 Lecturer, Bendigo College of Advanced Education, La Trobe University 1988-99 Senior lecturer, Monash University (Caulfield Campus) 1997 M.A. Fine Art, Monash University SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1967 Princes Hill Gallery, Melbourne 1968 Princes Hill Gallery, Melbourne 1974 Flinders Gallery, Geelong 1976 ‘Wendy Stavrianos’, Tolarno Gallery, Melbourne 1978 ‘Reflections of Darwin’, Tolarno Gallery, Melbourne ‘Fragments of Days That Have Become Memories’, Ray Hughes Gallery, Brisbane 1980 ‘Wendy Stavrianos’, Gallery A, Sydney 1 NICHOLAS THOMPSON GALLERY 1982 ‘Moments in Landscape’, Gallery A, Sydney 1983 ‘Earthskins’, Tolarno Gallery, Melbourne 1986 ‘The Night Series’, Tolarno Gallery, Melbourne 1987 ‘The Lake Mungo Night Drawings’, Tolarno Gallery, Melbourne ‘Summer Roses, Winter Dreams’, Greenhill Galleries, Perth 1989 ‘Veiled in Memory and Reflection’, The Art Gallery (renamed Luba Bilu Gallery), Melbourne 1991 ‘Drawing Retrospective’, Adam Gallery, Melbourne, courtesy Luba Bilu Gallery 1992 ‘Mantles of Darkness’, Luba Bilu Gallery, Melbourne 1994 ‘A Tremulous November’, Luba Bilu Gallery, Melbourne ‘The Gatherers and the Night City’, Luba Bilu Gallery, Melbourne ‘Mantles of Darkness’, touring exhibition to Ararat Gallery (11 March-24 April); Castlemaine Art Gallery (15 May-12 June); Geelong Art Gallery (17 June-17 July); McClelland Art Gallery, Langwarrin (11 September-9 October) 1995 ‘Mantles of Darkness’, Nolan Gallery, Canberra 1996 ‘W. -

Annual Report 2013–14

2013–14 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 ANNUAL REPORT 2013–14 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Tom Roberts Act 1975. Miss Minna Simpson 1886 oil on canvas The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is to be 59.5 x 49.5 cm an inspiration for the people of Australia. Purchased with funds donated by the National Gallery of Australia Council and Foundation in honour of Ron Radford AM, Director The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National of the National Gallery of Australia (2004–14), 2014. 100 Works for Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, 100 Years corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. (back cover) Polonnaruva period (11th–13th century) In 2013–14, the National Gallery of Australia received Sri Lanka appropriations from the Australian Government Standing Buddha 12th century totalling $49.615 million (including an equity injection bronze of $16.453 million for development of the national 50 x 20 x 20 cm art collection), raised $29.709 million, and employed Geoffrey White OAM and Sally White OAM Fund, 2013. 100 Works 257.93 full-time equivalent staff. for 100 Years © National Gallery of Australia 2014 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

Sad Slide in Prize Swamp by Sasha Grishin

Canberra Times Page 1 of 2 07-May-2011 Page: 20 Panorama By: Sasha Grishin Market: Canberra Circulation: 32116 Type: Capital City Daily Size: 669.53 sq.cms Frequency: MTWTFS- Sad slide in prize swamp The Archibald, Wynne and Sulman scene over sensibility; Fiona Lowry's portrait of Tim Silver is dull and formulaic and Tim Storrier's hollow self- hits new lows, Sasha Grishin writes portrait is frankly a bit silly. Nicolas Harding's portrait of Hugo Weaving is a very well-handled traditional I ast year I was convinced that the standard expressionist portrait. There is another unconvincing in the Archibald, Wynne and Sulman prize Adam Cullen portrait loosely based on the actor exhibitions had reached rock bottom. Charles Waterstreet. Del Kathryn Barton is Sadly I was wrong, this year the standard increasingly a disappointment as an artist, her portrait is even lower and excavation has of the actress Cate Blanchett and family is glam and commenced. unconvincing, the work of a decorative society According to the conditions of the Archibald and painter. Wynne bequests, the winners have to be decided by The Salon de Refuses, showing a selection of rejects the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, but from the Archibald and the Wynne, has a stronger when these conditions were set most of the trustees selection of portraits, an excellent and deeply moving were practising artists. Today, under the Art Gallery self-portrait of Guy Warren at the age of 90; a quirky of New South Wales Act 1980, the gallery's board portrait by Wendy Sharpe of Judy Cassab with a comprises 11 trustees at least two of whom shall be model, an excellent small sell-portrait by Graeme knowledgeable and experienced in the visual arts-.