The Long-Term Consequences of the Clean Air Act of 1970∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

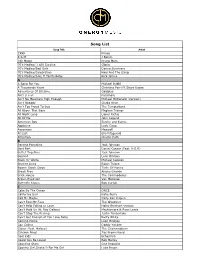

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Bruno Mars Ft. Travie Mccoy All I Need

Bruno Mars ft. Travie McCoy All I Need C#min F#min # ## # 4 Ó Œ ‰ ≈ r ‰ ≈ r ≈ Œ ‰ ≈ r & 4 œ œ œ. œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ Su gar co ca andho ney Thats ? #### 4 ∑ 4 w C#min ˙ F#min ˙ A 4 # ## # ‰ ≈ r ‰ œ. j ‰ & œ œ. œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ. œ œ j what you taste like tome Nowallœ œ œ I need is yourœ 4 ? # ## # ˙ ˙ w F#wmin C#min C#min 7 # ## # j j j œ. & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ sex to wash it down uh come here girl right nowœ œ 7 # ? ## # w ˙ ˙ w [Verse 1: Travie McCoy] [Verse 2: Travie McCoy] I’m a British boy so I can British things The world is ours Like nibble on your earlobe and let your body sing Put your head back, see the stars You’re my violin and I’m a string I like you just the way you are like Bruno Mars With every breath you take I won’t let it sting I know I can, call me Laz So let me in open the doors I love your thighs, I love your ass What yours is mine, what mine is yours Now give me your flower ‘cause I’ma give advance Where’s your pussy, give me your paws And I’m about to die, without a pass And I don’t mind if it’s you goin’ through my drawers I hope, think you can keep a secret before I ask Keep it clean ‘cause we gettin’ in a mess Oh no oh no you’re runnin’ Baby girl, yeah you’re better in the flash My tongue just like you’re cocoa I heard from your friends that I’m better than your ex Oh no oh no I think you need some cream upon you And if you real then I’m better than your next You think I got chick, what’s her name Banoffee pie, you’re my sweet talk I ain’t lying you’re my man That’s one of the reasons that you’re my sweetheart You’re the only picture inside my frame So when I meet us repeat fast Let’s wash it down with sex, no champagne Why don’t we just take it slow so we love [Hook: Bruno Mars] Sugar, cocoa and honey ............................ -

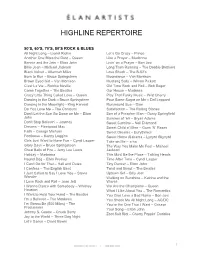

Highline Repertoire

HIGHLINE REPERTOIRE 50’S, 60’S, 70’S, 80’S ROCK & BLUES All Night Long – Lionel Richie Let’s Go Crazy – Prince Another One Bites the Dust – Queen Like a Prayer – Madonna Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Livin’ on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Long Train Running – The Doobie Brothers Black Velvet – Allannah Miles Love Shack – The B-52’s Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen Moondance – Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett C’est La Vie – Robbie Neville Old Time Rock and Roll – Bob Seger Come Together – The Beatles Our House – Madness Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Play That Funky Music – Wild Cherry Dancing in the Dark – Bruce Springsteen Pour Some Sugar on Me – Def Leppard Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest Runaround Sue – Dion Do You Love Me – The Contours Satisfaction – The Rolling Stones Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me – Elton Son of a Preacher Man – Dusty Springfield John Summer of ’69 – Bryan Adams Don’t Stop Believin’ – Journey Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Dreams – Fleetwood Mac Sweet Child o’ Mine – Guns ‘N’ Roses Faith – George Michael Sweet Dreams – Eurythmics Footloose – Kenny Loggins Sweet Home Alabama – Lynyrd Skynyrd Girls Just Want to Have Fun – Cyndi Lauper Take on Me – a-ha Glory Days – Bruce Springsteen The Way You Make Me Feel – Michael Great Balls of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Jackson Holiday – Madonna This Must Be the Place – Talking Heads Hound Dog – Elvis Presley Time After Time – Cyndi Lauper I Can’t Go for That – Hall and Oates Tiny Dancer – Elton John -

Adam David Song List

ADAM DAVID SONG LIST Artist Song 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Adelle Hello Rolling In The Deep Someone Like You Allen Stone Is This Love Unaware Amy Winehouse Back To Black Rehab Valerie Avicii Wake Me Up Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Aint No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Black Sabbath War Pigs Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone Bob Marley Dont Worry About A Thing I Shot The Sheriff No Woman No Cry Stir It Up Bob Seger Turn The Page Night Moves Bobby Mcferrin Dont Worry Be Happy Bon Jovi Livin On A Prayer Bruno Mars Grenade When I Was Your Man Bryan Adams Summer Of 69 Carlos Santana Maria Maria Cheap Trick I Want You To Want Me Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Citizen Cope Sideways Coldplay Clocks Viva La Vida Yellow Counting Crows Mr Jones Cream White Room Creedence Clearwater Revival Have You Ever Seen The Rain David Guetta Titanium Dobie Gray Drift Away Don Mclean American Pie Eagles Hotel California Take It Easy Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Eric Clapton Change The World Layla Nobody Knows You When Youre Down And Out Tears In Heaven Etta James At Last Extreme More Than Words Fleetwood Mac Landslide Foreigner Cold As Ice Foster The People Pumped Up Kicks Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Girl From Ipanema Fun We Are Young Gavin Degraw I Dont Want To Be Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gorillaz Clint Eastwood Gotye Somebody That I Used To Know Grateful Dead Casey Jones Franklins Tower Green Day Good Riddance Time Of Your Life Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O Mine Live Incubus Drive Pardon Me Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Somewhere Over The Rainbow What A Wonderful -

String Love Complete Song Lists

String Love Complete(ish) Song Lists Our repertoire is always growing, check back frequently! ROCK AND POP 1 2 3 4 – Plain White T’s 21 Guns – Green Day 100 Years – Five For Fighting A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Addicted To You - Avicii Adore You – Miley Cyrus Adventure of a Lifetime – Coldplay All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor All I Want Is You – U2 All My Love – Led Zeppelin All Of Me – John Legend All These Things That I’ve Done – The Killers All You Need Is Love – The Beatles American Idiot – Green Day Animals – Matthew Garrix Animaniacs – Rueger / Stone Annie’s Song – John Denver Ants Marching – Dave Matthews Band Applause – Lady Gaga Aqualung – Jethro Tull Atlas – Coldplay Back In Black – AC/DC Bang Bang – Jessie J The Battle Of Evermore – Led Zeppelin Beautiful Day – U2 Beautiful Life – Ace of Base Best Day Of My Life – American Authors Better Together – Jack Johnson Birthday – Katy Perry Bittersweet Symphony – The Verve Black Dog – Led Zeppelin Blackbird – The Beatles Blank Space – Taylor Swift Blue Tango – Leroy Anderson Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Boom Clap – Charli XCX Bridge Over Troubled Water – Simon and Garfunkle Bring Me To Life – Evanescence Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Burn – Ellie Goulding Can’t Help Falling In Love – Elvis Presley Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Can’t Take My Eyes Off You – Frankie Valli Candle In The Wind – Elton John Chandalier – Sia Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Cheerleader – OMI Clocks – Coldplay Come Away With Me – Norah Jones Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Cotton-Eyed -

The Walkons Repertoire

THE WALKONS REPERTOIRE BALLADS Blackbird, Something The Beatles All Of Me, Ordinary People John Legend Stand By Me Ben E. King Oh My Love John Lennon Piano Man Billy Joel I Hope You Dance LeAnn Womack Make You Feel My Love Bob Dylan Amazed Lonestar I’m on Fire Bruce Springsteen Let’s Get it on Marvin Gaye A Song For You Donny Hathaway Turn me On Nora Jones Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley I’ve Been Loving You For Too Long Otis Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Redding Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Crazy Patsy Cline At Last Etta James When A Man Loves A Woman (Michael Bolton) Percy Sledge Landslide Fleetwood Mac Fields of Gold Sting Wanted Hunter Hayes Pillowtalk Zayne You Are So Beautiful To Me Joe Cocker 90’S All The Small Things Blink 182 Fast Car, Gimme One Reason Tracy Smooth (Rob Thomas) Carlos Santana Chapman You Gotta Be Des’ree Meet Virginia Train Save Tonight Eagle-Eye Cherry Semi-Charmed Life Third Eye Blind Change The World Eric Clapton When Love Comes to Town U2 w/ BB King Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Island in The Sun Weezer My Own Worst Enemy Lit Santeria , What I Got Sublime 1 80’S ROCK / POP Take on me A-Ha Sledgehammer Peter Gabriel Livin’ On A Prayer Bon Jovi Easy Lover Phil Collins Pour Some Sugar On Me Def Leppard Message in a Bottle, Every Breath you Money for Nothing Dire Straits Take, The Police Paradise City, Sweet Child O’ Mine Guns ‘N Every Little Thing She Does is Magic, So Roses Lonely Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey Rule The World Tears For Fears Footloose Kenny Loggins Jump Van Halen Hit Me With -

Ain't No Sunshine – Bill Withersain't Too Proud To

Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill WithersAin’t too . Have I Told You Lately – Van Morrison Proud to Beg – Temptations . Heartbreak Warfare – John Mayer . All Shook Up - Evlis . Here Comes the Sun – The Beatles . All Summer Long – Kidd Rock . Here I Am Baby – Al Green . All You Need Is Love – Beatiles . Hey Soul Sister - Train . Amber - 311 . Hey There Delilah – Plain White T’s . Angel - Shaggy . Higher Ground – Stevie Wonder . Ants Marching – Dave Matthews . Hit The Road Jack – Ray Charles . Arms Wide Open – Creed . Hot Hot Hot - Arrow . Baby I Love Your Way – Peter Frampton . Hotel California – The Eagles . Banana Pancakes – Jack Johnson . How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You) James . Beast of Burden – The Rolling Stones Taylor . Beautiful – Snoop Dog . I Can See Clearly Now – Johnny Nash . Better Together – Jack Johnson . I Can’t Stand The Rain – Turner/Seal . Billionaire – Bruno Mars . I Don’t Need No Doctor – John Mayer . Black Bird – Beatles . I Don’t Trust Myself – John Mayer . Black Magic Woman- Santana . I Wish – Stevie Wonder . Breakdown – Tom Petty . If I Only Had a Brain – Harold Arlen (Wizard . Brick House - Commodores of Oz) . Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison . If You’re Gonna Leave – Raul Midon . Can’t Buy Me Love - Beatles . I'm Yours – Jason Mraz . Can’t Help Falling in Love – Elvis/UB40 . Is This Love – Bob Marley . Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia) – Us3 . It’s Alright- Curtis Mayfield . Carolina In My Mind – James Taylor . Jack & Diane – John Melloncamp . Cecilia – Simon & Garfunkel . Jamaica Farewell – Harry Belefonti . Change The World – Eric Clapton . Jimi Thing – Dave Matthews . Come Together - Beatles . -

Every Breath You Take (Sting) by the Police Every Breath You Take and Every Move You Make Every Bond You Break, Every Step You T

Free Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for personal education purposes only Every breath you take (Sting) by The Police Every breath you take and every move you make Every bond you break, every step you take I'll be watchin' you Every single day and every word you say Every game you play, every night you stay I'll be watchin' you Oh, can't you see You belong to me How my poor heart breaks With every step you take Every move you make and every vow you break Every smile you fake, every claim you stake I'll be watchin' you Since you've gone I been lost without a trace I dream at night, I can only see your face I look around but it's you I can't replace I feel so cold and I long for your embrace I keep cryin', baby, baby, please Oh, can't you see You belong to me How my poor heart breaks With every step you take Every move you make and every vow you break Every smile you fake, every claim you stake I'll be watchin' you Every move you make, every step you take I'll be watchin' you I'll be watchin' you (every breath you take, every move you make, every bond you break, every step you take) I'll be watchin' you (every single day, every word you say, every game you play, every night you stay) I'll be watchin' you (every move you make, every vow you break, every smile you fake, every claim you stake) I'll be watchin' you (every single day, every word you say, every game you play, every night you stay) I'll be watchin' you (every breath you take, every move you make, every bond you break, every step you take) I'll be watchin' you (every single day, every word you say, every game you play, every night you stay) I'll be watchin' you (every move you make, every vow you break, every smile you fake, every claim you stake) I'll be watchin' you (every single day, every word you say, every game you play, every night you stay) I'll be watchin' you Free Music resources from www.traditionalmusic.co.uk for personal education purposes only. -

The Biggest Hits of All: the Hot 100'S All-Time Top 100 Songs

The Biggest Hits of All: The Hot 100's All-Time Top 100 Songs billboard.com/articles/news/hot-100-turns-60/8468142/hot-100-all-time-biggest-hits-songs-list Adele, Rihanna, Ed Sheeran, Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Elton John, Chubby Checker, Mariah Carey, Shania Twain & Whitney Houston Getty Images; Photo Illustration by Quinton McMillan As part of Billboard's celebration of the 60th anniversary of our Hot 100 chart this week, we're taking a deeper look at some of the biggest artists and singles in the chart's history. Here, we revisit the ranking's 100 biggest hits of all-time. On Aug. 4 1958, Billboard launched the Hot 100, forever changing pop music -- or at least how it's measured. Sixty years later, the chart remains the gold-standard ranking of America's top songs each week. And while what goes into a hit has changed (bye, bye jukebox play; hello, streaming!), attaining a spot on the list -- or better yet, a coveted No. 1 -- i s still the benchmark to which artists explore, from Ricky Nelson on the first to Drake on the latest. Which brings us to the hottest-of-the-hot list the 100 most massive smashes over the charts six decades. 1/10 1. The Twist - 1960 Chubby Checker The only song to rule the Billboard Hot 100 in separate release cycles (one week in 1960, two in 1962), thanks to adults catching on to the song and its namesake dance after younger audiences popularized them. 2. Smooth - 1999 Santana Feat. Rob Thomas 3. -

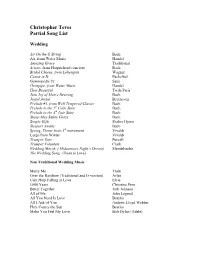

Christopher Teves Partial Song List

Christopher Teves Partial Song List Wedding Air On the G String Bach Air, from Water Music Handel Amazing Grace Traditional Arioso, from Harpsichord concerto Bach Bridal Chorus, from Lohengrin Wagner Canon in D Pachelbel Gymnopedie #1 Satie Hornpipe, from Water Music Handel How Beautiful Twila Paris Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring Bach Joyful Joyful Beethoven Prelude #1, from Well Tempered Clavier Bach Prelude to the 1st Cello Suite Bach Prelude to the 4th Lute Suite Bach Sheep May Safely Graze Bach Simple Gifts Shaker Hymn Sleepers Awake Bach Spring, Theme from 1st movement Vivaldi Largo from Winter Vivaldi Trumpet Tune Purcell Trumpet Voluntary Clark Wedding March, ( Midsummer Night’s Dream) Mendelssohn The Wedding Song, (There is Love) Non Traditional Wedding Music Marry Me Train Over the Rainbow (Traditional and Iz version) Arlen Cant Help Falling in Love Elvis 1000 Years Christina Perri Better Together Jack Johnson All of Me John Legend All You Need Is Love Beatles All I Ask of You Andrew Lloyd Webber Here Comes the Sun Beatles Make You Feel My Love Bob Dylan (Adele) Cocktail Hour Annie’s Song John Denver Angel Jack Johnson Arthur’s Theme Bacharach, Sager, Cross, Allen Ashokan Farewell Payne At Last Etta James Black Orpheus Luiz Bonfá Blackbird Beatles Best of My Love Eagles Better Together Jack Johnson Blue Moon Rodgers and Hart Blowin in the Wind Bob Dylan Breathe Faith Hill Carolina in My Mind James Taylor Chasing Cars Snow Patrol Choros #1 Villa Lobos Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis (Weiss, Peretti, Creotore) Classical Gas Mason Williams -

Popular/Contemporary String Quartet

1 Complete List of Pops/Contemporary String Quartet (Updated January 2021) T = Trio and String Quartet Across the Universe - Beatles Adagio - Secret Garden Adventure of a Lifetime - Coldplay Ain’t No Mountain High Enough T All I Ask of You - Phantom of the Opera All I Want is You - U2 All My Love – Led Zeppelin All My Loving - Beatles All Of Me – John Legend T All of the Lights – Kanye West Always With Me – Spirited Away All You Need is Love - Beatles T Amazed - Lancaster Amazing Grace And I Love Her - Beatles And So It Goes - Billy Joel Angel – Sarah McLachlan Annie’s Song - John Denver T Ashokan Farewell -The Civil War, PBS As Time Goes By A Time For Us - Romeo and Juliet At Last – Etta James Awake My Soul - Mumford and Sons Beautiful Day - U2 T Beauty and the Beast Because - Beatles Beethoven’s 5 Secrets – The Piano Guys Bella’s Lullaby – Twilight Ben – Michael Jackson Besame Mucho Best Day of My Life - American Authors Better Together – Jack Johnson Beyond The Sea Birthday – Beatles Bittersweet Symphony Blackbird - Beatles) Arranged by John Reed for The Hampton [Rock] String Quartet Blank Space – Taylor Swift Bless The Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Blueberry Hill – Fats Domino Blue Moon 2 Bohemian Rhapsody – Queen T The Book of Love – Scrubs T Bouree – Jethro Tull Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Him Home - Les Miserables Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison California Dreaming – Beach Boys Candle in the Wind - Elton John Can’t Buy Me Love – The Beatles Can’t Help Falling in Love – Elvis Presley/Crazy Rich Asians T Can’t Stop The Feeling -

Childrens Songs : 80 Songs Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHILDRENS SONGS : 80 SONGS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation | 148 pages | 01 Apr 2012 | Hal Leonard Corporation | 9781458410993 | English | Milwaukee, United States ChildrenS Songs : 80 Songs PDF Book So, not that tragic. On "Push It," all-gal Queens hip-hop trio Salt-N-Pepa made pop magic via a seemingly simple combination of Casio beats; a few big, dumb keyboard stabs; and a lot of impassioned, steamy cries of "Ooh, baby baby. Bush was discovered when barely into her teens, knocking out genius tunes on a piano in her cozy Kent, England, home. Ever wonder why Frozen 's Elsa seems to be more popular than Anna, even though Anna has more screen time and is arguably the bigger heroine of the movie? Her parents hail from India, she was born in San Francisco and the whole family relocated to France when she was still quite young. Okay, so maybe Air Supply isn't the coolest band in the world. You can unsubscribe at any time. Bono wrote U2's epic ballad about being torn between his life as a musician and a family man. This is longing on a supernatural scale, and Tyler holds her own against the thundering arrangement as she roars out some of the least quiet desperation ever known to pop music. The third single from Guns N' Roses' shining debut, 's Appetite for Destruction , it was the band's first and only number one single. Mastering the Spanish rap interlude in your favorite pop song adds an element of challenge to the experience—and when you finally master that bit of the song, the satisfaction and pride you feel is beyond compare.