David M. Liston*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 2 Paradeplaat Last Change Artiest: Titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley

Radio 2 Paradeplaat last change artiest: titel: 1977 1 Elvis Presley Moody Blue 10 2 David Dundas Jeans On 15 3 Chicago Wishing You Were Here 13 4 Julie Covington Don't Cry For Me Argentina 1 5 Abba Knowing Me Knowing You 2 6 Gerard Lenorman Voici Les Cles 51 7 Mary MacGregor Torn Between Two Lovers 11 8 Rockaway Boulevard Boogie Man 10 9 Gary Glitter It Takes All Night Long 19 10 Paul Nicholas If You Were The Only Girl In The World 51 11 Racing Cars They Shoot Horses Don't they 21 12 Mr. Big Romeo 24 13 Dream Express A Million In 1,2,3, 51 14 Stevie Wonder Sir Duke 19 15 Champagne Oh Me Oh My Goodbye 2 16 10CC Good Morning Judge 12 17 Glen Campbell Southern Nights 15 18 Andrew Gold Lonely Boy 28 43 Carly Simon Nobody Does It Better 51 44 Patsy Gallant From New York to L.A. 15 45 Frankie Miller Be Good To Yourself 51 46 Mistral Jamie 7 47 Steve Miller Band Swingtown 51 48 Sheila & Black Devotion Singin' In the Rain 4 49 Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers Egyptian Reggae 2 1978 11 Chaplin Band Let's Have A Party 19 1979 47 Paul McCartney Wonderful Christmas time 16 1984 24 Fox the Fox Precious little diamond 11 52 Stevie Wonder Don't drive drunk 20 1993 24 Stef Bos & Johannes Kerkorrel Awuwa 51 25 Michael Jackson Will you be there 3 26 The Jungle Book Groove The Jungle Book Groove 51 27 Juan Luis Guerra Frio, frio 51 28 Bis Angeline 51 31 Gloria Estefan Mi tierra 27 32 Mariah Carey Dreamlover 9 33 Willeke Alberti Het wijnfeest 24 34 Gordon t Is zo weer voorbij 15 35 Oleta Adams Window of hope 13 36 BZN Desanya 15 37 Aretha Franklin Like -

Travel Guide Berlin

The U2tour.de Travel Guide Berlin English Version Version Januar 2020 © U2tour.de The U2Tour.de – Travel Guide Berlin The U2Tour.de Travel Guide Berlin You're looking for traces of U2? Finally in Berlin and don't know where to go? Or are you travelling in Berlin and haven't found Kant Kino? This has now come to an end, because now there is the U2Tour.de- Travel Guide, which should help you with your search. At the moment there are 20 U2 sights in our database, which will be constantly extended and updated with your help. Original photos and pictures from different years tell the story of every single place. You will also receive the exact addresses, a spot on the map and directions. So it should be possible for every U2 fan to find these points with ease. Credits Texts: Dietmar Reicht, Björn Lampe, Florian Zerweck, Torsten Schlimbach, Carola Schmidt, Hans ' Hasn' Becker, Shane O'Connell, Anne Viefhues, Oliver Zimmer. Pictures und Updates: Dietmar Reicht, Shane O'Connell, Thomas Angermeier, Mathew Kiwala (Bodie Ghost Town), Irv Dierdorff (Joshua Tree), Brad Biringer (Joshua Tree), Björn Lampe, S. Hübner (RDS), D. Bach (Slane), Joe St. Leger (Slane), Jan Année , Sven Humburg, Laura Innocenti, Michael Sauter, bono '61, AirMJ, Christian Kurek, Alwin Beck, Günther R., Stefan Harms, acktung, Kraft Gerald, Silvia Kruse, Nicole Mayer, Kay Mootz, Carola Schmidt, Oliver Zimmer and of course Anton Corbijn and Paul Slattery. Maps from : Google Maps, Mapquest.com, Yahoo!, Loose Verlag, Bay City Guide, Down- townla.com, ViaMichelin.com, Dorling Kindersley, Pharus Plan Media, Falk Routenplaner Screencaps : Rattle & Hum (Paramount Pictures), The Unforgettable Fire / U2 Go Home DVD (Uni- versal/Island), Pride Video, October Cover, Best Of 1990-2000 Booklet, The Unforgettable Fire Cover, Beautiful Day Video, u.v.m. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Bruno Mars Ft. Travie Mccoy All I Need

Bruno Mars ft. Travie McCoy All I Need C#min F#min # ## # 4 Ó Œ ‰ ≈ r ‰ ≈ r ≈ Œ ‰ ≈ r & 4 œ œ œ. œ œ œ. œ œ œ œ œ. œ Su gar co ca andho ney Thats ? #### 4 ∑ 4 w C#min ˙ F#min ˙ A 4 # ## # ‰ ≈ r ‰ œ. j ‰ & œ œ. œ œ œ. œ. œ œ œ œ. œ œ j what you taste like tome Nowallœ œ œ I need is yourœ 4 ? # ## # ˙ ˙ w F#wmin C#min C#min 7 # ## # j j j œ. & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ Œ sex to wash it down uh come here girl right nowœ œ 7 # ? ## # w ˙ ˙ w [Verse 1: Travie McCoy] [Verse 2: Travie McCoy] I’m a British boy so I can British things The world is ours Like nibble on your earlobe and let your body sing Put your head back, see the stars You’re my violin and I’m a string I like you just the way you are like Bruno Mars With every breath you take I won’t let it sting I know I can, call me Laz So let me in open the doors I love your thighs, I love your ass What yours is mine, what mine is yours Now give me your flower ‘cause I’ma give advance Where’s your pussy, give me your paws And I’m about to die, without a pass And I don’t mind if it’s you goin’ through my drawers I hope, think you can keep a secret before I ask Keep it clean ‘cause we gettin’ in a mess Oh no oh no you’re runnin’ Baby girl, yeah you’re better in the flash My tongue just like you’re cocoa I heard from your friends that I’m better than your ex Oh no oh no I think you need some cream upon you And if you real then I’m better than your next You think I got chick, what’s her name Banoffee pie, you’re my sweet talk I ain’t lying you’re my man That’s one of the reasons that you’re my sweetheart You’re the only picture inside my frame So when I meet us repeat fast Let’s wash it down with sex, no champagne Why don’t we just take it slow so we love [Hook: Bruno Mars] Sugar, cocoa and honey ............................ -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE STOP & GO 3-D Premieres this May/June 2012 Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Leiden, Berlin, Pula and Zagreb Stop-Motion Animation Festival + Exhibition EUROPE— Stop & Go 3-D screening premiere with the Doppler Stop Exhibition. May 3rd – June 3r, 2012 the San Francisco Bay Area conceived stop-motion animation festival will travel to the Netherlands, Germany and Croatia for the world premiere of Stop & Go 3-D. The Stop & Go program was developed in 2008 and showcases animations that use stop-motion techniques to explore visual language, tell stories and make social commentaries. Stop & Go 3-D features a new series of stop-motion animations by 27 contemporary visual artists and filmmakers from around the world. The program dramatically plays with our visual senses through the artist’s use of stobing effects, afterimages, anaglyphic experiments, optical elements and three- dimensional spoofs. The animations in this program were chosen from a world- wide open call for submissions and by invitation. Five of the animations in the program require the audience to wear red/cyan-colored glasses to fully engage with the work. In Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Berlin and Zagreb Stop & Go 3-D will screen alongside Doppler Stop an exhibition of optically and perceptually challenging artworks. Pairing the screening alongside an exhibition is designed to illuminate a deeper connection between the artists’ primary practices of painting, drawing and sculpture and the processes used in their animations. The Stop & Go 3-D screening program is curated by Sarah Klein, an artist, educator, and curator whose own practice includes animation, and the Doppler Stop exhibition is curated by Mel Prest, an artist and educator. -

Exploring Myths & Legends

Exploring Myths & Legends • Recommended childrenʹs books • Writing activities • Drawing, mask-making and other creative activities • Ideas for sharing childrenʹs stories and writing • Writing organizers and templates Myths & Legends Myths are stories told aloud that were passed down from generation to generation for thousands of years. Myth is from the Greek word, “mythos” — which means “word of mouth” — oral stories shared from person to person. Myths have helped people from different cultures to make sense of the natural world, before scientific discoveries guided our understanding. Myths explained the reason for an erupting volcano, or thunder and lightning, or even night following day. Many myths feature gods, goddesses or humans with supernatural powers. Kids may be familiar with Zeus, the king of all gods in Greek mythology, who could throw lightning bolts from the sky down to Earth. Myths often include a lesson, suggesting how humans should act. A legend is a traditional story about a real place and time in the past. Legends are rooted in the truth, but have changed over time and retelling and taken on fictional elements. The heroes are human (not gods and goddesses) but they often have adventures that are larger-than-life. The tales of Odysseus from Ancient Greece and King Arthur from Medieval England are two examples of legends. Myths and legends can be found throughout the world. Many of these traditional stories feature similar subjects, but express the unique culture and history of the regions where they are from. There are flood myths from India, aboriginal legends from Australia, Taino creation stories from Puerto Rico, the legend of the Chinese zodiac, Norse myths, and many more. -

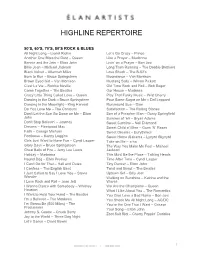

Highline Repertoire

HIGHLINE REPERTOIRE 50’S, 60’S, 70’S, 80’S ROCK & BLUES All Night Long – Lionel Richie Let’s Go Crazy – Prince Another One Bites the Dust – Queen Like a Prayer – Madonna Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Livin’ on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Long Train Running – The Doobie Brothers Black Velvet – Allannah Miles Love Shack – The B-52’s Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen Moondance – Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett C’est La Vie – Robbie Neville Old Time Rock and Roll – Bob Seger Come Together – The Beatles Our House – Madness Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Play That Funky Music – Wild Cherry Dancing in the Dark – Bruce Springsteen Pour Some Sugar on Me – Def Leppard Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest Runaround Sue – Dion Do You Love Me – The Contours Satisfaction – The Rolling Stones Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me – Elton Son of a Preacher Man – Dusty Springfield John Summer of ’69 – Bryan Adams Don’t Stop Believin’ – Journey Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Dreams – Fleetwood Mac Sweet Child o’ Mine – Guns ‘N’ Roses Faith – George Michael Sweet Dreams – Eurythmics Footloose – Kenny Loggins Sweet Home Alabama – Lynyrd Skynyrd Girls Just Want to Have Fun – Cyndi Lauper Take on Me – a-ha Glory Days – Bruce Springsteen The Way You Make Me Feel – Michael Great Balls of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Jackson Holiday – Madonna This Must Be the Place – Talking Heads Hound Dog – Elvis Presley Time After Time – Cyndi Lauper I Can’t Go for That – Hall and Oates Tiny Dancer – Elton John -

Adam David Song List

ADAM DAVID SONG LIST Artist Song 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Adelle Hello Rolling In The Deep Someone Like You Allen Stone Is This Love Unaware Amy Winehouse Back To Black Rehab Valerie Avicii Wake Me Up Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Aint No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Black Sabbath War Pigs Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone Bob Marley Dont Worry About A Thing I Shot The Sheriff No Woman No Cry Stir It Up Bob Seger Turn The Page Night Moves Bobby Mcferrin Dont Worry Be Happy Bon Jovi Livin On A Prayer Bruno Mars Grenade When I Was Your Man Bryan Adams Summer Of 69 Carlos Santana Maria Maria Cheap Trick I Want You To Want Me Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Citizen Cope Sideways Coldplay Clocks Viva La Vida Yellow Counting Crows Mr Jones Cream White Room Creedence Clearwater Revival Have You Ever Seen The Rain David Guetta Titanium Dobie Gray Drift Away Don Mclean American Pie Eagles Hotel California Take It Easy Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Eric Clapton Change The World Layla Nobody Knows You When Youre Down And Out Tears In Heaven Etta James At Last Extreme More Than Words Fleetwood Mac Landslide Foreigner Cold As Ice Foster The People Pumped Up Kicks Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The Moon Girl From Ipanema Fun We Are Young Gavin Degraw I Dont Want To Be Gnarls Barkley Crazy Gorillaz Clint Eastwood Gotye Somebody That I Used To Know Grateful Dead Casey Jones Franklins Tower Green Day Good Riddance Time Of Your Life Guns N' Roses Sweet Child O Mine Live Incubus Drive Pardon Me Israel Kamakawiwo'ole Somewhere Over The Rainbow What A Wonderful -

String Love Complete Song Lists

String Love Complete(ish) Song Lists Our repertoire is always growing, check back frequently! ROCK AND POP 1 2 3 4 – Plain White T’s 21 Guns – Green Day 100 Years – Five For Fighting A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Addicted To You - Avicii Adore You – Miley Cyrus Adventure of a Lifetime – Coldplay All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor All I Want Is You – U2 All My Love – Led Zeppelin All Of Me – John Legend All These Things That I’ve Done – The Killers All You Need Is Love – The Beatles American Idiot – Green Day Animals – Matthew Garrix Animaniacs – Rueger / Stone Annie’s Song – John Denver Ants Marching – Dave Matthews Band Applause – Lady Gaga Aqualung – Jethro Tull Atlas – Coldplay Back In Black – AC/DC Bang Bang – Jessie J The Battle Of Evermore – Led Zeppelin Beautiful Day – U2 Beautiful Life – Ace of Base Best Day Of My Life – American Authors Better Together – Jack Johnson Birthday – Katy Perry Bittersweet Symphony – The Verve Black Dog – Led Zeppelin Blackbird – The Beatles Blank Space – Taylor Swift Blue Tango – Leroy Anderson Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Boom Clap – Charli XCX Bridge Over Troubled Water – Simon and Garfunkle Bring Me To Life – Evanescence Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Burn – Ellie Goulding Can’t Help Falling In Love – Elvis Presley Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Can’t Take My Eyes Off You – Frankie Valli Candle In The Wind – Elton John Chandalier – Sia Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Cheerleader – OMI Clocks – Coldplay Come Away With Me – Norah Jones Come On Eileen – Dexy’s Midnight Runners Cotton-Eyed -

The Walkons Repertoire

THE WALKONS REPERTOIRE BALLADS Blackbird, Something The Beatles All Of Me, Ordinary People John Legend Stand By Me Ben E. King Oh My Love John Lennon Piano Man Billy Joel I Hope You Dance LeAnn Womack Make You Feel My Love Bob Dylan Amazed Lonestar I’m on Fire Bruce Springsteen Let’s Get it on Marvin Gaye A Song For You Donny Hathaway Turn me On Nora Jones Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley I’ve Been Loving You For Too Long Otis Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeran Redding Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Crazy Patsy Cline At Last Etta James When A Man Loves A Woman (Michael Bolton) Percy Sledge Landslide Fleetwood Mac Fields of Gold Sting Wanted Hunter Hayes Pillowtalk Zayne You Are So Beautiful To Me Joe Cocker 90’S All The Small Things Blink 182 Fast Car, Gimme One Reason Tracy Smooth (Rob Thomas) Carlos Santana Chapman You Gotta Be Des’ree Meet Virginia Train Save Tonight Eagle-Eye Cherry Semi-Charmed Life Third Eye Blind Change The World Eric Clapton When Love Comes to Town U2 w/ BB King Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Island in The Sun Weezer My Own Worst Enemy Lit Santeria , What I Got Sublime 1 80’S ROCK / POP Take on me A-Ha Sledgehammer Peter Gabriel Livin’ On A Prayer Bon Jovi Easy Lover Phil Collins Pour Some Sugar On Me Def Leppard Message in a Bottle, Every Breath you Money for Nothing Dire Straits Take, The Police Paradise City, Sweet Child O’ Mine Guns ‘N Every Little Thing She Does is Magic, So Roses Lonely Don’t Stop Believin’ Journey Rule The World Tears For Fears Footloose Kenny Loggins Jump Van Halen Hit Me With -

Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol. 46, No. 1

Vol. 46, No. 1 March 2017 Journal of the International Planetarium Society Online PDF: ISSN 23333-9063 Special Feature: Women in Astronomy Page 18 Ad space (bleed) : 8.625×10.75 inch Trim : 8.375 x 10.5 inch Live area : 7.45×9.3nch Executive Editor Sharon Shanks 484 Canterbury Ln Boardman, Ohio 44512 USA +1 330-783-9341 [email protected] March 2017 Webmaster Alan Gould Vol. 46 No. 1 Lawrence Hall of Science Planetarium Articles University of California Berkeley CA 94720-5200 USA 8 Update: Vision2020 initiatives, what’s coming up next [email protected] Jon Elvert Advertising Coordinator 8 IPS Position Statement: International Collaboration Dale Smith and Science Communication (See Publications Committee on page 3) 9 Call for 2018 IPS Awards and Fellows Nominations Membership Manos Kitsonas Individual: $65 one year; $100 two years 10 IPS international competitions winners Institutional: $250 first year; $125 annual renewal Susan Reynolds Button Library Subscriptions: $50 one year; $90 two years 14 International Day of Planetaria changes All amounts in US currency Direct membership requests and changes of 16 About the “Turtle in the Sky” story Andy Kreyche address to the Treasurer/Membership Chairman 17 Turtle in the Sky Andy Kreyche 18 Celebrating women in astronomy Sharon Shanks Printed Back Issues of Planetarian 19 Women in Science NASA IPS Back Publications Repository maintained by the Treasurer/Membership Chair 20 Susan Murbana: Mother, wife, and African lady who loves (See contact information on next page) the stars Sharon Shanks 21 Women of NASA are women of LEGO, too Final Deadlines Sharon Shanks March: January 21 June: April 21 24 Filmmaking for Fulldome: Best Practices and Guidelines September: July 21 for Immersive Cinema (Part II) December: October 21 Ka Chun Yu, Dan Neafus, Ryan Wyatt Associate Editors 38 Teaching about the angle of insolation, a.k.a. -

Ain't No Sunshine – Bill Withersain't Too Proud To

Ain’t No Sunshine – Bill WithersAin’t too . Have I Told You Lately – Van Morrison Proud to Beg – Temptations . Heartbreak Warfare – John Mayer . All Shook Up - Evlis . Here Comes the Sun – The Beatles . All Summer Long – Kidd Rock . Here I Am Baby – Al Green . All You Need Is Love – Beatiles . Hey Soul Sister - Train . Amber - 311 . Hey There Delilah – Plain White T’s . Angel - Shaggy . Higher Ground – Stevie Wonder . Ants Marching – Dave Matthews . Hit The Road Jack – Ray Charles . Arms Wide Open – Creed . Hot Hot Hot - Arrow . Baby I Love Your Way – Peter Frampton . Hotel California – The Eagles . Banana Pancakes – Jack Johnson . How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You) James . Beast of Burden – The Rolling Stones Taylor . Beautiful – Snoop Dog . I Can See Clearly Now – Johnny Nash . Better Together – Jack Johnson . I Can’t Stand The Rain – Turner/Seal . Billionaire – Bruno Mars . I Don’t Need No Doctor – John Mayer . Black Bird – Beatles . I Don’t Trust Myself – John Mayer . Black Magic Woman- Santana . I Wish – Stevie Wonder . Breakdown – Tom Petty . If I Only Had a Brain – Harold Arlen (Wizard . Brick House - Commodores of Oz) . Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison . If You’re Gonna Leave – Raul Midon . Can’t Buy Me Love - Beatles . I'm Yours – Jason Mraz . Can’t Help Falling in Love – Elvis/UB40 . Is This Love – Bob Marley . Cantaloop (Flip Fantasia) – Us3 . It’s Alright- Curtis Mayfield . Carolina In My Mind – James Taylor . Jack & Diane – John Melloncamp . Cecilia – Simon & Garfunkel . Jamaica Farewell – Harry Belefonti . Change The World – Eric Clapton . Jimi Thing – Dave Matthews . Come Together - Beatles .