Changing the System: Indeterminacy and Politics in the Early 1970S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons

The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts Michael Parsons Leonardo Music Journal, Vol. 11, Not Necessarily "English Music": Britain's Second Golden Age. (2001), pp. 5-11. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0961-1215%282001%2911%3C5%3ATSOAVA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-V Leonardo Music Journal is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Sep 29 14:25:36 2007 The Scratch Orchestra and Visual Arts ' The Scratch Orchestra, formed In London in 1969 by Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons and Howard Skempton, included VI- sual and performance artists as Michael Parsons well as musicians and other partici- pants from diverse backgrounds, many of them without formal train- ing. -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

A Clear Apparance

A Clear Apparence 1 People in the UK whose music I like at the moment - (a personal view) by Tim Parkinson I like this quote from Feldman which I found in Michael Nyman's Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond; Anybody who was around in the early fifties with the painters saw that these men had started to explore their own sensibilities, their own plastic language...with that complete independence from other art, that complete inner security to work with what was unknown to them. To me, this characterises the music I'm experiencing by various composers I know working in Britain at the moment. Independence of mind. Independence from schools or academies. And certainly an inner security to be individual, a confidence to pursue one's own interests, follow one's own nose. I donʼt like categories. Iʼm not happy to call this music anything. Any category breaks down under closer scrutiny. Post-Cage? Experimental? Post-experimental? Applies more to some than others. Ultimately I prefer to leave that to someone else. No name seems all-encompassing and satisfying. So Iʼm going to describe the work of six composers in Britain at the moment whose music I like. To me itʼs just that: music that I like. And why I like it is a question for self-analysis, rather than joining the stylistic or aesthetic dots. And only six because itʼs impossible to be comprehensive. How can I be? Thereʼs so much good music out there, and of course there are always things I donʼt know. So this is a personal view. -

Booklet Tilbury.Qxd:Booklet DROUET

John Tilbury - Piano John Tilbury has given concerts and broadcasts of new music, including first performances, in many countries around the world. His solo recordings include Cage's Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano, from the seventies, and more recently the music of Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton, Christian Wolff and the complete solo piano works of Morton Feldman. He is also well known as an improvising musician, through his membership of AMM, one of the most distinguished and influential free improvisation groups to have emerged in the sixties. In preparation for a talk I was to give on Feldman and Skempton, I wrote down the following notes as a kind of aide-mémoire. John Tilbury 1996 On Softness Softness – also length, and brevity. But 'not for its own sake’. ‘Virtuosity of restraint’ (Skempton). Alice (in Wonderland) had to accustom herself to new dimensions. Soft 'as possible'. Relative. Degree and quality of softness depends on the acoustical and the psychological. Awareness of this dynamic quality within softness creates an extraordinary variety. Softness draws the audience into the music - it encourages attentiveness and alertness. It also demands a ‘transcendental’ listening in its search for a revelatory experience. Softness heightens consciousness; also enhances the consciousness, for example, of the idiosyncrasies of the instrument at which one sits. On the unintended This respect for the unintended embodies the notion for the interpreter of nowness, of uniqueness. Accidentalness is an active component, to be convincingly contextualized. The music responds to the contingencies of venue, of temperature, etc. etc. This, together with an emphasis on the sensual and physical qualities of the art of performance, creates an indivisibility of musician and instrument and at best of music and audience; an at one-ness. -

Jems: Journal of Experimental Music Studies - Reprint Series

12 April 2012 Jems: Journal of Experimental Music Studies - Reprint Series The Music of Howard Skempton Michael Parsons Originally published in Contact no. 21 (Autumn 1980), pp. 12-16. Reprinted with the kind permission of the author. Since 1967, when he first moved to London to study privately with Cornelius Cardew, Howard Skempton has pursued an even and consistent course in his music, focusing and refining his central concerns. His concentration on the quality of sound and his economy of means are already clearly evident in early works such as A Humming Song (1967), Snowpiece and September Song (both 1968) and Piano Piece 1969.1 These piano pieces are predominantly static and without development, presenting in chance-determined sequence a limited number of carefully pre-selected notes or chords. The usual playing direction is ‘very slowly and quietly’, and there is little sense of forward momentum; each individual sound is allowed to resonate freely, and successive notes or chords are related to each other only by juxtaposition. There is a clear relationship with the earlier music of Feldman, but in Skempton’s pieces the means are even more economical. A Humming Song was actually written in April 1967 when Skempton was 19, a few months before he began studying with Cardew. It is for a pianist who is asked also to sustain certain notes by humming; this, incidentally, requires considerable control and relaxation and disproves the false notion that Skempton’s music is always technically easy to perform. This composition is worth describing in some detail, since it uses methods which can be found in many of Skempton’s other works. -

Programme Notes

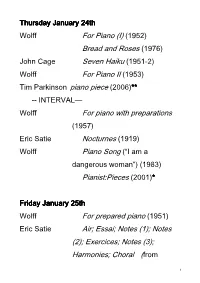

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007. -

Philip Thomas - Piano

Something New, Something Old, Something Else (2) Philip Thomas - piano Laurence Crane Chorale for Howard Skempton (1997) Howard Skempton senza licensa (1974) Laurence Crane Derridas (1985-6) 1. Jacques Derrida Goes To A Nightclub 2. Jacques Derrida Goes To A Massage Parlour 3. Jacques Derrida Goes To The Supermarket 4. Jacques Derrida Goes To The Beach Laurence Crane Birthday Piece for Michael Finnissy (1996) Michael Finnissy First Political Agenda (1989-2006) WORLD PREMIERE (complete) 1. Wrong place. Wrong time. 2. Is there any future for new music? 3. You know what kind of sense Mrs. Thatcher made. --- INTERVAL --- John White Piano Sonatas 154 (‘Carbon Footprints in the Snow’), 166 , 162 (‘MayDay’) (2007-8) Howard Skempton Second Gentle Melody (1975) Bryn Harrison I-V (2003) Laurence Crane Piano Piece No.23 'Ethiopian Distance Runners' (2009) WORLD PREMIERE This concert is the second of two given as part of the five40five series, grouped together under the title Something New, Something Old, Something Else . The primary intention is that a major new work is commissioned from a composer whose music I find to be radical, original and ultimately inspiring. Then, an older work by the same composer is chosen to go alongside the new work and the programme is completed with works by other composers, from any musical period or style, that might demonstrate connections, traces, influences, or even disparities. These works have been selected after discussions between the composers and myself. The two composers who have written new works for this project – Markus Trunk for the concert in May, and Laurence Crane for tonight’s concert - are composers whose music I respond to at a very intuitive level. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Parsons, Michael. 1980. ‘The Music of Howard Skempton’. Contact, 21. pp. 12-16. ISSN 0308-5066. ! [!] MICHAEL PARSONS The ft\.usic of Howard Skempton SINCE 1967, when he first moved to London to study sequences. These pieces are tonally static: both of the privately with Comelius Cardew, Howard Skempton has Highland Dances have an open-fifth drone throughout, pursued an even and consistent course in his music, and Waltz has been well described by Michael Nyman as a focusing and refining his central concerns. His paradigm of experimental flatness and uniformity. 2 concentration on the quality of sound and his economy of With First Prelude (1971) there emerges a more definite means are already clearly evident in early works such as A sense of harmonic movement. This is, however, always Humming Song (1967), Snowpiece and September Song contained within narrow limits and is never allowed to (both 1968) and Piano Piece 1969. 1 These piano pieces are achieve the dynamic, developing quality of a chord predominantly static and without development, progression in traditional music. There is, rather, presenting in chance-determined sequence a limited oscillation around a harmonic centre, focusing attention number of carefully pre-selected notes or chords. The on it instead of using it as a point of departure or for usual playing direction is 'very slowly and quietly', and dramatic contrast. The uniform repetition of each chord, there is little sense of forward momentum; each individual which gives to this and similar pieces some apparent sound is allowed to resonate freely, and successive notes rhythmic momentum, is in fact used simply as a way of or chords are related to each other only by juxtaposition. -

Just the Job for That Lazy Sunday Afternoon’: British Readymades and Systems Music

‘Just the job for that lazy Sunday afternoon’: British Readymades and Systems Music An amplification of a paper given at the First International Conference on Minimalism, University of Wales, Bangor, 31 August–2 September 2007 Virginia Anderson, University of Nottingham THIS PAPER is concerned with definitions and their change and application over time and space. Take the term ‘systems music’, or its associated terms, ‘systems’ and ‘sys- temic music’, also ‘systematic’ music. Nobody seems to know exactly what these terms mean. In fact, the use of the term ‘systems’ became so vague that although it had appeared in the first New Grove of 1980, ‘systems’ disappeared as a definition in New Grove II in 2001. This would imply that ‘system’ is not only an old term, but a meaningless one. Is the term ‘system’ just another synonym for ‘process’, a way of structuring minimal music? Is the term ‘system’ is just outdated slang for repetitive minimalism? ‘System’ has been considered to be either a synonym or an archaism for repetitive music, sometimes both, at different times and to different scholars. However, there is a reason for bringing back the term ‘systems music’, with a clear definition. If we return ‘systems music’ to the group of British experimental com- posers who first used it, we find that it is also of use as applied to some music by this group today. Even so, we must clarify the use of the term ‘system’ within British experimental composition, because the way that each composer uses it depends on the time and situation in which it is used. -

Cornelius Cardew's Music for Moving Images

Cornelius Cardew’s Music for Moving Images: Some Preliminary Observations Clemens Gresser Some initial thoughts Whereas Cardew’s autonomous music (especially within a modernist or more experimental framework) has received some attention, his music for moving images and for radio has been little discussed to date.1 Such applied music seems to fit none of what could be seen as the four core areas of Cardew’s musical activity: 1. his modernist and avant-garde music (all his works before starting his early experiments with the Scratch Orchestra),2 2. his experimental and improvisational music (Scratch Orchestra, AMM), 3. his overtly political and tonal music (mainly songs, and often performed by PLM3 or the Songs for Our Society Group), or 4. his programmatic, indirectly political music (mostly piano music, such as Thälmann Variations).4 However, film and radio music might also feature (or can have traces of) any of the approaches found in other areas of his oeuvre. This research was supported by a three-month British Library Research Break (an annual scheme for BL staff). I am extremely grateful to my former colleagues in Music Collections, and particularly to Nicolas Bell and Sandra Tuppen, for allowing me to have access to uncatalogued material and generally answering all my questions; to Trish Hayes (BBC Written Archives), for helping me with BBC archival materials; and to Susan Reed for not interrupting my research work with queries relating to my previous library position. 1 John Tilbury, Cornelius Cardew (1936-1981): A Life Unfinished (Matching Tye, Essex, 2008), and Eddie Prévost (ed.), Cornelius Cardew: A Reader. -

British Minimalism and Post-Minimalism in Piano Duets and Two-Piano Works 18 June 2013

British minimalism and post-minimalism in piano duets and two-piano works 18 June 2013 Programme Michael Parsons Rhythm Studies II (1971) Howard Skempton No Great Shakes (1989) John White Untitled Piano Duet (1966) Piano Duet 13 (from 1st Set of Duets (1974)) Dave Smith Swings (1974) Christopher Hobbs Pretty Tough Cookie (c.1972) Piano Duet 11 (from 1st Duet Set (1974)) The Remorseless Lamb (exc.) (1970) Dave Smith A Gay Romp (1974) About the composers Michael Parsons was born in 1938. Co-founder, with Cornelius Cardew and Howard Skempton of the Scratch Orchestra he has been closely associated with visual artists of the Systems group. Like Skempton, with whom he has worked as a duo, his music is characterized by an economical use of material and clarity of structure. Since 1956, John White has composed a considerable amount for the concert platform, dance and theatre productions, electronic media and experimental ensembles that he has initiated. His works are written in a wide range of styles and include 175 piano sonatas and much for piano duet and 2 pianos. He is Head of Music at the Drama Centre, London. Dave Smith read music at Magdalene College, Cambridge in the late 1960s, joined the Scratch Orchestra and performed in various composer/performer groups in the 1970s. These included a keyboard duo with John Lewis as well as later groups with Parsons, Skempton, White and Gavin Bryars. Much of his own music since the mid-1980s is for solo piano. He teaches at the University of Hertfordshire. Christopher Hobbs studied with Cornelius Cardew at the Royal Academy of Music. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Huddersfield Repository University of Huddersfield Repository Thomas, Philip The Music of Laurence Crane and a Post-Experimental Performance Practice Original Citation Thomas, Philip (2016) The Music of Laurence Crane and a Post-Experimental Performance Practice. Tempo, 70 (275). pp. 5-21. ISSN 0040-2982 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/28879/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ The Music of Laurence Crane and a Post-Experimental Performance Practice1 Introduction It has become commonplace to talk about Laurence Crane’s music as transforming the familiar into the unfamiliar.2 Triads (mostly major, but minor too), simple stepwise melodies (usually only three or four notes), tonic-dominant harmony, simple pulse-based movement – the impact is startling, even for listeners accustomed to some of the more extreme compositional tendencies of recent years as well as to the tonal epiphanies of minimalism.