STUDIES of KUTTIKRISHNA MARAR on SANSKRIT WORKS Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

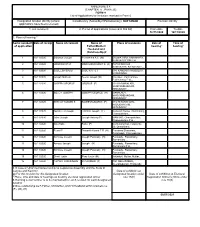

Sslc Examination Concession March - 2014 Revenue District : Alappuzha

SSLC EXAMINATION CONCESSION MARCH - 2014 REVENUE DISTRICT : ALAPPUZHA EDUCATIONAL DISTRICT : KUTTANAD Admission Concessions Category Sl. Centre No. (As per Granted in the Name of Student of Name of School No. Code the School SSLC Examination Disability Register) March 2014 AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 1 RESHMA. G MR 46039 4278 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 2 SRUTHYMOL. B MR 46039 4271 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 3 SRUTHYMOL SUBASH MR 46039 4274 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 4 ANJU. S MR 46039 4280 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 5 RESHMA. K.S MR 46030 4431 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 6 MARIYAMMA CHACKO MR 46039 4260 KAINADY GRACE MARK AJ JOHN MEMORIAL HS SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, 7 SOORYA. P.S MR 46039 4275 KAINADY GRACE MARK 8 ANUJITH M. DAS OH BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 6080 SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME 9 ADARSH. K.C LD BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 6005 EXTRA TIME 10 SARATH. S LD BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 7077 EXTRA TIME 11 MANU SOURIAR LD BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 6014 SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME 12 ATHIRA. J LD BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 7128 SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME 13 AJAY THOMAS LD BBM HS VAISYAMBHAGOM 46023 6085 EXTRA TIME SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, GRACE MARK, EXEMPTED DEVA MATHA HS 14 MIDHUN. K.S MR 46032 6847 FROM GRAPH, DRAWING, CHENNAMKARY DIAGRAMS AND GEOMETRICAL FIGURES SCRIBE, EXTRA TIME, GRACE MARK, EXEMPTED 15 VIPIN KUMAR. V MR G.H.S. -

District Wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt

District wise IT@School Master District School Code School Name Thiruvananthapuram 42006 Govt. Model HSS For Boys Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42007 Govt V H S S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42008 Govt H S S For Girls Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42010 Navabharath E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42011 Govt. H S S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42012 Sr.Elizabeth Joel C S I E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42013 S C V B H S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42014 S S V G H S S Chirayinkeezhu Thiruvananthapuram 42015 P N M G H S S Koonthalloor Thiruvananthapuram 42021 Govt H S Avanavancheri Thiruvananthapuram 42023 Govt H S S Kavalayoor Thiruvananthapuram 42035 Govt V H S S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42051 Govt H S S Venjaramood Thiruvananthapuram 42070 Janatha H S S Thempammood Thiruvananthapuram 42072 Govt. H S S Azhoor Thiruvananthapuram 42077 S S M E M H S Mudapuram Thiruvananthapuram 42078 Vidhyadhiraja E M H S S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42301 L M S L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42302 Govt. L P S Keezhattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42303 Govt. L P S Andoor Thiruvananthapuram 42304 Govt. L P S Attingal Thiruvananthapuram 42305 Govt. L P S Melattingal Thiruvananthapuram 42306 Govt. L P S Melkadakkavur Thiruvananthapuram 42307 Govt.L P S Elampa Thiruvananthapuram 42308 Govt. L P S Alamcode Thiruvananthapuram 42309 Govt. L P S Madathuvathukkal Thiruvananthapuram 42310 P T M L P S Kumpalathumpara Thiruvananthapuram 42311 Govt. L P S Njekkad Thiruvananthapuram 42312 Govt. L P S Mullaramcode Thiruvananthapuram 42313 Govt. L P S Ottoor Thiruvananthapuram 42314 R M L P S Mananakku Thiruvananthapuram 42315 A M L P S Perumkulam Thiruvananthapuram 42316 Govt. -

Microsoft Word

www.archdiocesechanganacherry.org 2018 Transfer and Appointments 2018 February 13 (13.02.2018) Very Rev./Rev. Frs Transferred from Transferred to Alencherry Isaac Thiruvalla Chancellor Athikalam James Aickarachira Paipadu Lourdes Chakalackal Soji MCBS Ambalapuzha Cheeramvelil Jacob Madappally Aickarachira Chethipuzha Varghese Rajamattam Retired Edathiparampil MST Anchal, Pazhayeroor Relieved Kakkanattu Joseph Paipadu Nalukody Sec. Abp Powathil/Bp Tharayil Kalapura Toms Sehion Kunnamthanam Muringoor Retreat Centre Kalathil Reny CMI Cheepunkal Kattoor Thomas Koilmuck f. Mithrakary Kayamkulathusserry Thomas Manalady Kezhaplackal Philipose Pacha-chekidikadu Thiruvallam – Vellayany Kizhakkemury Joe Kumarankary Leave Kocherry Damianose Thekkekara St Johns Narbonapuram Kochuchira Joseph Narbonapuram Leave for Prayer Kochuparampil George Pacha-Chekidikkadu Manimala F Kudilil James Changanacherry Metro Rajamattam Kulathumkal Thomas Ettawah CHASS, Kumarankary Kuzhippally Jacob Veroor Leave Maliyil Thomas Koduppunna Sick Leave Manavath Varkey Champakulam F Manalady Manjerikalam Sebastian Manimala F Pandy Mavelil John MCBS Vadakkeamichakary Mozhoorcheruvelil Karumady USA Mullakariyil Jose IIT Delhi (Research) Nadackal Mathew Anchal, Pazhayeroor Naduvilekkalam Jacob Pandy Mayam Nelluvely Emmanuel South African Cheruvandoor Nereyath Antony Manimala Holy Magi F Pacha-Chekidikadu Ottalankal Chacko Mayam Relieved Palakkacherry Chacko Thiruvallam Kandankary Palakunnel Cherian Vezhapra Retired, Priests Home Parappallil Scaria Kandankary Thiruvalla Poovatholil -

Tet Centres 21.07.2012

List of Schools selected for TET Examination on 25/08/2012 SL.NO DEO Name of Schools 1 KASARAGOD GHSS Uppala GHSS Kumbla GHSS Kasaragod NHSS Perdala Chattanchal HSS 2 KANHANGAD GHSS Udma Durga HSS Kanhangad Rajas HSS Nileswar GHSS Periya GHSS Pilicode 3 KANNUR St. Michels Anglo Indian HSS Kannur St. Theresas AIG HSS Kannur GVHSS Kannur GVHSS for Girls Payyambam, Kannur Govt. Town HSS Kannur 4 THALASSERY BEMP HSS Thalassery St. Joseph HSS Thalassery MM HSS Thalassery GVHSS Koduvally GVHSS Kadirur 5 WAYANAD GVHSS Mananthavadi GVHSS Kalpetta GSVHSS Sulthan Bethery GHSS Meenangadi GHSS Kaniyambatta 6 VADAKARA GVHSS Boys Madapally GVHSS Meppayoor GHSS Kuttiady BEMHS Vatakara Thiruvangoor HSS 7 KOZHIKODE Govt. Ganapath HS for Boys Kozhikode Govt Ganapath HS Kallai GVHSS Meenchantha GVHSS Payyanakkal Govt Model Ganpath Girls HSS Chalappuram 8 WANDOOR GMVHSS Nilambur GHSS Edakkara VMCGHSS Wandoor GHSS Pattikkad GHSS Areacode 9 THAMARASSERY GHSS Koduvally GVHSS Thamarassery Govt Boys HSS GHS Naduvannur Kunnamangalam HSS 10 MALAPPURAM GBHSS Malappuram GRHSS Kottakkal GVHSS Kondotty GV HSS Perinthalmanna GBHSS Manjeri 11 TIRUR MIHSS (Boys) Ponnani GHSS Kuttipuram GBHSS Tirur SNMHSS Parappanangadi GVHSS Chelari 12 OTTAPPALAM GHSS Vattenad GHSS Cherpulassery GVHS Koppam GHSS Vadanamkurissi GHS Ottappalam 13 PALAKKAD GMMGHSS Palakkad PMG HSS Palakkad BEM HSS Palakkad GHSS Big Bazar DBHS Thachampara 14 THRISSUR Chaldean Syrian HSS Thrissur Vivekodayam Boys HSS Thrissur Holy Family CGHS Thrissur Sacret Heart CGHS Thrissur St. Clares CGHS Thrissur 15 IRINJALAKUDA RM HSS Aloor St. Thomas EMHS Aloor BVHS Kallettumkara GVHSS Chalakudy GSHS Astamichira 16 CHAVAKKAD St. Joseph HSS Pavaratty MAS MHSS Venmenad CKS Girls HS Pavaratty GHSS Chavakkad MRR MHS Kootungal 17 ALUVA GGHSS Aluva St. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 10.03.2019To16.03.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 10.03.2019to16.03.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 CHARIVU PURAYIDATHTHIL, KUTTIKKATTUPA 11.03.19 541 279 IPC & SI SURESHBABU 1 BINU CK KESAVAN 43/M KOTTAMURIYIL, CHENGANNUR STATION BAIL DI 11.15HRS 185 OF MV ACT MK MULAKKUZHA, CHENGANNUR PAANAM PADIKKAL MALAYIL,KURICHIVATTO 11.03.19 SI SURESHBABU 2 THAMPIKKUTTY PV JOSEPH 41/M ITI Jn 542 279 IPC CHENGANNUR STATION BAIL M KARAYIL, 13.20HRS MK KIDANGANNUR MANNARAKKAM ISHO G PUTHTHANVEETI 11.03.19 543 4 r/w 21 3 VIJESH VIJAYAN 28/M VEEDU, VANMAZHI CHENGANNUR SANTHOSHKUM STATION BAIL PPADI 14.00HRS of MMDR ACT MURI, PANDANAD AR KALLINKAL VEEDU, SI PP KIZHAKKENADA 11.03.19 545 279 IPC & 4 ANILKUMAR 30/F VARAYANNUR MURI, CHENGANNUR MUHAMMADKU STATION BAIL KUNJIRAMAN Jn 19.00HRS 185 OF MV ACT KOYIPRAM VILLAGE NJU KIDANGANNUR VEEDU, KRISHNAMOHA 11.03.19 5 MOHANKUMAR 26/M MAZHUKKEERMURI, CHENGANNUR 546 107 CrPC CHENGANNUR SI SV BIJU STATION BAIL N 19.15HRS THIRUVANVANDOOR KIZHAVARA MODIYIL, OMANAKKUTTA 11.03.19 547 118(a) OF 6 BHASKARAN 47/M ANGADIKKAL ANGADIKKAL CHENGANNUR SI PRAKASH STATION BAIL N 23.15HRS KP ACT MURI,CHENGANNUR AALAMPALLITHTHARA, PANDAVANPARA 12.03.19 548 118(a) OF 7 RAHUL REGHU 29/M AALTHARA Jn CHENGANNUR SI SV BIJU STATION BAIL SOUTH, PERISSERI, 09.00HRS KP ACT PULIYOOR VALYAYYATH -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 23.11.2014 to 29.11.2014

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 23.11.2014 to 29.11.2014 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, Rank which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 KAAPA ACT 2007 Sec:3(1) Detention Order A C Kannan @ Katti Kannantharaveli, 23.11.2014 at No.SC.6/40537/1 Ouseppachan, SI 1 Soman M-28 Kalavoor Mannancherry kannan Mannanchery P/W-22 14.30 Hrs 4 dtd 18.11.14 of Police, from the Hon'ble Mannancherry Dist. Collector, Alappuzha A C Kizhakkethayyil Cr.1038/14 U/s 24.11.2014at Ouseppachan, SI 2 Subhalal Sadasivan M-44 Nikarthil, Aryad South Kalavoor Jn. 279 IPC & 185 Mannancherry Bailed by Police 11.30Hrs of Police, P/W-3 od MV Act Mannancherry Cr.1039/14 U/s A C Pallipparambu, 24.11.2014at 118(i) of KP Act Ouseppachan, SI 3 Vipin Pathrose M-29 Mararikulam South P/W- Omanappuzha Mannancherry Bailed by Police 12.45Hrs & 6(b) r/w 24 of of Police, 14 COTPA Act Mannancherry Cr.823/14 U/s A.C Kodiveettil, Cherthala 24.11.2014at 4 Rajesh Pavithran M-34 Mannancherry 494, 498(A) Mannancherry Ouseppachan, SI Bailed by Police South P/W-2 13.45Hrs ,109,34 IPC Mannancherry Panayil veettil, Cr.1040/14 U/s A.C Chinnammakkav 24.11.2014at 5 Hareesh Ramanan M-22 Mararikulam South P/W- 279 IPC & 185 Mannancherry Ouseppachan, SI Bailed by Police ala Jn. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 08.11.2015 to 14.11.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 08.11.2015 to 14.11.2015 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Pedekkeyanchira, 1193/15, U/S 41/15, 9.11.2015, K G Prathap Bail from 1 Joshy Thankappan Aroor P.O, Aroor Aroor 15(c) of KA Aroor Male 15.10 Hrs chandran, SHO station P/W-7 Act Kattupalli House, 1193/15, U/S 29/15, 9.11.2015, K G Prathap Bail from 2 Kalesh Thankappan Aroor P.O, Aroor Aroor 15(c) of KA Aroor Male 15.10 Hrs chandran, SHO Station P/W-16 Act 1193/15, U/S 39/15 Thadathil Hose, 9.11.2015, K G Prathap Bail 3 Babu Isac Thomas Aroor 15(c) of KA Aroor Male Kaduthuruthy 15.10 Hrs chandran, SHO fromstation Act Kalarickalparampil, 1194/15, U/S Krisha 44/15, 9.11.2015, K G Prathap Bail from 4 Sivan Aroor P.O, Aroor Aroor 15(c) of KA Aroor Panicker Male 16.10 Hrs chandran, SHO station P/W-16 Act Annithara nikarth, 1194/15, U/S 38/15 9.11.2015, K G Prathap Bail from 5 Binumon Sidhardhan Aroor P.O, Aroor Aroor 15(c) of KA Aroor Male 16.10 Hrs chandran, SHO station P/W-7 Act Thuruthil House, 1196/15 U/s Rajesh Ponnappan 39/15 11.11.2015 T A Joseph, SI Bail from 6 Aroor P.O, Aroor Aroor 279 IPC 185 of Aroor Kumar Pillai Male , 18.20 Hrs of Police station P/w-7 MV Act Kuzhisserinikarth, 1199/15 U/s P V Udayan 18/15 12.11.2015 Bail from 7 Syamkumar Chandran Ezhupunna P.O, Ezhupunna 118(a) -

(CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for Inclusion

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): KUTTANAD Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Solomon Joseph Pennamma K C (M) ERUMATHRA, KAINAKARY, KAINAKARY SOUTH, , 2 16/11/2020 MANEESH P M MADHUSUDHAN P K (F) PUTHENCHIRA , KAINAKARY, KAINAKARY, , 3 16/11/2020 SUBEESH SABU SABU K G (F) 234, KANDAKATHUSSERY, KUNNUMMA, , 4 16/11/2020 Joseph Mathew Beena Joseph (M) Parasseri, Pulincunnoo, Pulincunnoo P O, , 5 16/11/2020 JOSEPH GEORGE GEORGE (F) 13/2UA MANALADI, VAISYAMBHAGAM, NEDUMUDY, , 6 16/11/2020 SOLGY JOSEPH JOSEPH GEORGE (H) MANALADY, VAISYAMBHAGAM, NEDUMUDY, , 7 16/11/2020 AKSHAY KUMAR S SAJEEVKUMAR N (F) 11/239 KUNCHAYIL, NADUBHAGAM, NEDUMUDY, , 8 16/11/2020 Aparna Lal Joseph Lalichan Joseph (F) Nelluvelil House, Amichakary, Champakulam, , 9 16/11/2020 Jebin Joseph Joseph Antony (F) MANGAD, Champakulam, Champakulam P O, , 10 16/11/2020 Anju Sabu Sabu (F) Kochukanjickal, Colony No 60, Onnamkara, , 11 16/11/2020 Resmi P Prasanth Kumar T R (H) Prasanna Bhavanam, Pullangady, Champakulam, , 12 16/11/2020 Annoose Joseph Joseph Puravady (H) Puravady , Ramankary, Ramankary , , 13 16/11/2020 Annuse Joseph -

Details of Upgradation Work

Details of Upgradation Work Thiruvananthapuram Kollam Alappuzha Pathanamthitta Kottayam Idukki Ernakulam Thrissur Palakkad Malappuram Kozhikkode Wayanad Kannoor Kasaragod Back to first page A. S T.S Date of Date of Work name Amount in Sl Amount in commencem completion Lakh No. District AS No Lakhs ent of work of work GO(MS) Nemom Punnamoodu road bet. Km. 0/00 to 2/800. 35 No.1809/PWD Dated 1 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Thiruvananthapuram Vizhinjam road Km. 5/500 to 7/00 and 9/00 to 45 No.1809/PWD Dated 10/500. 2 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Karakonam Vlamkulam road km. 3/500 to 5/400. 40 No.1809/PWD Dated 3 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Vattavila Prayinmoodu road km. 0/00 to 2/479. 30 No.1809/PWD Dated 4 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Udiyankulangara Kulathoor Chavady road km. 4/500 to 6/500. 40 No.1809/PWD Dated 5 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Mampuzhakkara road 0/00 to 4/200. 110 No.1809/PWD Dated 6 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Neyyattinkara Marayamuttom road. Km. 0/00 to 3/00. 25 No.1809/PWD Dated 7 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Aruvippuram Perumkadavila road Km. 0/00 to 2/00. 25 No.1809/PWD Dated 8 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Perukavu Vizhavoor Choozhattukotta road . 19 No.1809/PWD Dated 9 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Oottukuzhy Cherukadu 20 No.1809/PWD Dated 10 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 GO(MS) Chowalloor NSS High school road 20 No.1809/PWD Dated 11 Thiruvananthapuram 30-11-2010 Back to first page A. -

CHASS Kuttanadu Flood Loss & Damages Consolidation Data

Changanacherry Social Service Society - CHASS Kuttanadu Flood Loss & Damages Consolidation Data Latrin House House House Paddy Tubers Plantne Animals Domestic Domestic Vegetable Sl. hold items Panchayath Parish Total loss No. Total Total Loss Amount Partial Loss Amount Total No. Amount Total No. Amount Acre Amount Total No. Amount Total No. Amount Total No. Amount Total No. Amount 1 Kizhakke Mithrakary 39 14534000 163 5124000 138 3234000 188 5274700 1 25000 252 1427900 87 311700 137 556220 170 1598650 32086170 2 Mithrakary 11 4278000 156 7020000 117 2984580 167 4568932 12 360000 214 1456860 77 78450 98 217860 89 967845 21932527 3 Muttar Old 36 13700000 321 10846600 84 1182700 276 6774100 162 2370000 246 5260000 79 1475800 116 459950 122 728000 42797150 4 Muttar New 25 9700000 275 8745000 115 1746800 209 5853800 4 210000 163 1914050 24 149100 74 369250 102 2485040 31173040 MUTTAR 5 Muttar CMI 12 5600000 29 2097000 19 311000 39 1131500 46 609450 17 84500 22 65500 31 276050 10175000 6 Puthukary 47 10854500 240 14255000 149 2844500 319 9522500 38 680000 256 1733600 142 511350 181 590550 192 1875500 42867500 7 Edathua 26 11700000 42 3740000 51 1015000 51 2190000 2 40000 18685000 8 Koilmukku 17 4867800 175 7875000 21 315000 36 815000 19 304000 117 204750 36 64900 137 205500 14 182000 14833950 9 Koduppunna 14 7385000 90 3881000 52 1395000 115 2108500 44 952000 120 599100 63 227400 101 191925 45 301550 17041475 10 Thayamkary 15 6654000 165 6598000 29 435000 143 3095950 57 94050 114 302100 59 103250 136 496400 19 223250 18002000 11 Changamkary -

Kuttanad Total Ps:- 172

LIST OF POLLING STATIONS SSR-2021 DISTRICT NO & NAME :- 11 ALAPPUZHA LAC NO & NAME :- 106 KUTTANAD TOTAL PS:- 172 PS NO POLLING STATION NAME 1 Govt.U.P.S., Thottukadav ( South portion of south building), Chennamkary. 2 Govt.U.P.S., Thottukadav ( West portion of south building), Chennamkary. 3 Govt.S.N.D.P.L.P.S.,( East of Bhajanamadam), Chennamkary. 4 Govt.S.N.D.P.L.P.S.,( West of Bhajanamadam), Chennamkary. 5 S.N.D.P.H.S.,(South portion ),Kuttamangalam. 6 S.N.D.P.H.S.,(North portion ),Kuttamangalam. 7 St.Mary's H.S., (Eastern Building), Kainakary. 8 K.E.Carmel English Medium School, (Noth Portion of Western Building) Kainakary 9 K.E.Carmel English Medium School (Noth Portion of Western Building), Kainakary 10 Govt .H.S., Kuppappuram, ( North portion of main building),Kainakary. 11 Kainakary Govt.H.S.,Kuppappuram, ( East portion of North building) ,Kainakary. 12 Holly family G.H.S., ( South portion ), Kainakary. 13 Holly family G.H.S., ( North portion ), Kainakary. 14 Govt.U.P.S.Kainakary. (West portion of old building), Thottuvathala. 15 Thottuvathala Govt.U.P.S., ( North portion of new building), Kainakary. 16 C.M.S.Lower Primary School, Kunnumma (Eastern Portion) 17 Little Flower High School, Kunnumma (Main Building) PS NO POLLING STATION NAME 18 Little Flower High School, Kunnumma (Eastern Portion) 19 Govt. Lower Primary School, Veliyanadu North (Western Portion) 20 Govt. Lower Primary School, Veliyanadu North (Easterm Portion) 21 N.S.S.High School Kavalam (Eastern Portion) 22 N.S.S.High School, Kavalam (Western Portion) 23 N.S.S.High School Kavalam (Northern Portion) 24 Govt. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 01.11.2020To07.11.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 01.11.2020to07.11.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr No - 1527 / 2020 U/s 188 ,269 IPC & 118(e) KP Act GEORGEKUTTY, Karuvelil,Pavukkara,K KURATTI 07-11-2020 & Sec. 4(2)(a) BAILED BY 1 Gokul Krishnan Goplakrishnan 22 Male MANNAR SI OF POLICE urattissery,Mannar TEMPLE JN 19:10 r/w 5 of Kerala POLICE MANNAR Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Cr No - 1526 / 2020 U/s 188 ,269 IPC & 118(e) KP Act Puthen STORE 07-11-2020 & Sec. 4(2)(a) Gsi John BAILED BY 2 Rinso Biji 21 Male Purackal,Kurattissery, MANNAR JUNCTION 18:25 r/w 5 of Kerala Thomas POLICE Mannar Epidemic Diseases Ordinance 2020 Tharayoor mele Cr No - 1294 / puthenveedu Kodamthuruth 07-11-2020 2020 U/s BAILED BY 3 Vishnu prasad Rajashekaran 28 Male KUTHIATHODE G REMESAN Kunnathukal p. O u 18:15 279,283IPC,17 POLICE Kunnathukal p/w-12 7MVACT PUTHEN VEETIL NEAR Cr No - 1247 / 07-11-2020 JIJIN JOSEPH SI 4 RAGESH SARASAN 24 Male KARUVATTA P O AKHATHARA 2020 U/s 279 HARIPPAD ARRESTED 18:15 OF POLICE KARUVATTA SOUTH SCHOOL IPC Cr No - 1246 / MANALEL NEAR 2020 U/s 279 07-11-2020 JIJIN JOSEPH SI 5 AKHIL CHANDRA BABU24 Male KIZHAKKATHIL AKHATHARA IPC& 146 R/W HARIPPAD ARRESTED 17:35 OF POLICE KARUVATTA P O SCHOOL 196 OF MV ACT Cr No - 1125 / Mampra Thekkathil 2020 U/s 07-11-2020 BAILED BY 6 Aneesh Hasanar 37 Male House Vettiyar Vettiyar 118(a) of KP KURATHIKADU Niyas S 17:05 POLICE Thazhakara Act & 4(2)(j), 5 of KEDO Cr No - 1641 / 2020 U/s 269 IPC & Sec.