Placing Vulnerability at the Centre of Section 15(1) of the Charter: a Case Comment on Inglis V British Columbia (Minister of Public Safety)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appellants – Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Alberta

File No. 33340 SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEAL OF ALBERTA) BETWEEN: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF ALBERTA (MINISTER OF ABORIGINAL AFFAIRS AND NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT) and REGISTRAR, METIS SETTLEMENTS LAND REGISTRY APPELLANTS (Respondents) -and- BARBARA CUNNINGHAM and JOHN KENNETH CUNNINGHAM, LA WRENT (LAWRENCE) CUNNINGHAM, RALPH CUNNINGHAM, LYNN NOSKEY, GORDON CUNNINGHAM, ROGER CUNNINGHAM AND RAY STUART RESPONDENTS (Appellants) -and- ATTORNEY GENERAL OF QUEBEC ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ONTARIO INTERVENERS APPELLANTS' FACTUM Mr. Robert J. Normey Henry S. Brown, Q.C. Mr. David Kamal Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP Attorney General of Alberta Suite 2600 4th Floor 160 Elgin Street Bowker Building Ottawa, Ontario 9833 - 109th Street KIP 1C3 Edmonton, Alberta T5K2E8 Tel.: 780422-9532 Tel.: 613 233-1781 Fax: 780425-0307 Fax: 613 788-3433 [email protected] henry. [email protected] Counsel for the Appellants Agent for the Appellants -11- Mr. Kevin Feth Mr. Dougald E. Brown Field LLP Nelligan O'Brien Payne LLP Suite 2000 Suite 1500 10235 - 101 Street 50 O'Connor Street Edmonton, Alberta Ottawa, Ontario T5J 3GI KIP 6L2 Tel.: 780423-7626 Tel.: 613 231-8210 Fax: 780424-7116 Fax: 613 788-3661 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Respondents Agent for the Respondents Ms. Isabelle Harnois Mr. Pierre Landry Attorney General of Quebec Noill & Associes 2nd Floor III Champlain Street 1200 Route de l'Eglise Gatineau, Quebec Ste-Foy, Quebec J8X 3RI GlY 4MI Tel.: 418 643-1477 Tel.: 819771-7393 Fax: 418 646-1696 Fax: 819771-5397 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener Agent for the Intervener Attorney General of Quebec Attorney General of Quebec Attorney General of Saskatchewan Brian A. -

The Supreme Court of Canada and Constitutional (Equality) Baselines

Osgoode Hall Law Journal Volume 50, Issue 3 (Spring 2013) Rights Constitutionalism and the Canadian Charter of Article 7 Rights and Freedoms Guest Editors: Benjamin L. Berger & Jamie Cameron The uprS eme Court of Canada and Constitutional (Equality) Baselines Rosalind Dixon Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Special Issue Article Citation Information Dixon, Rosalind. "The uS preme Court of Canada and Constitutional (Equality) Baselines." Osgoode Hall Law Journal 50.3 (2013) : 637-668. http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/ohlj/vol50/iss3/7 This Special Issue Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Osgoode Hall Law Journal by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. The uprS eme Court of Canada and Constitutional (Equality) Baselines Abstract In its approach to defining “analogous grounds” for the purposes of subsection 15(1) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Supreme Court of Canada has adopted an unusual mix of broad and generous interpretation, and high formalism. This article argues that one potential reason for this is the degree of heterogeneity among the nine distinct enumerated grounds in section 15. Heterogeneity of this kind can produce quite different interpretive consequences, depending on whether a court adopts a direct, “multi- pronged,” or a more synthetic, “common denominator,” approach to the question of analogical development. The ourC t, over time, has implicitly shifted from the first to the second of these approaches. For comparative constitutional scholars, a lesson of Canadian Charter jurisprudence is thus that the number and scope of the analogical baseline categories in a constitution—and how courts approach their relationship to each other—can matter a great deal for the subsequent recognition of new constitutional categories. -

Genesis of the Duty to Consult & Supreme Court

THE GENESIS OF THE DUTY TO CONSULT AND THE SUPERME COURT The judicial genesis of the legal duty of consultation began with a series of Aboriginal right and title decisions providing the foundational principles of the duty to consult. Guerin Beginning prior to the repatriation of Canada’s constitution, the Supreme Court in Guerin1 found that the Crown had violated its fiduciary duty to the band by failing to consult with them when they accepted a lesser lease and unilaterally changed the legal position of the band, without their knowledge or consent. Justice Dickson stated “In obtaining, without consultation, a much less valuable lease than the promised, the Crown, breached the fiduciary obligation it owed the band.” Sparrow Then in 1990, the Supreme Court in Sparrow2 deliberated its first post 1982 Aboriginal rights case to explore the content of s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 19823 where the court expressly limited Crown power and conduct by affirming a duty to consult with West Coast Salish asserting their inherent and constitutionally protected right to fish through a ‘justification test’ where the duty to consult is one factor to be considered when justifying an infringement on Aboriginal rights. Van der Peet In 1996 the Supreme Court further developed foundational principles on the duty to consult in their adjudication of the definition of an Aboriginal right in R v Van der Peet.4 Van Der Peet is important for proving CHRs off reserve. Nikal Next in 1996, another Supreme Court decision constraining crown power and affirming the duty to consult regarding resources to which Aboriginal peoples make claim was made in Nikal, where Cory J. -

Case Comment on R. V. Kapp: an Analytical Framework for Section 25 of the Charter

Case Comment on R. v. Kapp: An Analytical Framework for Section 25 of the Charter Celeste Hutchinson* There is a significant void in the jurisprudence Un important vide subsiste dans la jurisprudence and literature regarding section 25 of the Canadian et dans la doctrine au sujet de l’article 25 de la Charte Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Consequently, there is canadienne des droits et libertés. Par conséquent, 2007 CanLIIDocs 140 no settled interpretation of either when it is triggered or l’interprétation de cet article demeure incertaine quant à the specific analytical framework that should apply. In la détermination des critères selon lesquels cet article R. v. Kapp, the British Columbia Court of Appeal est susceptible d’être invoqué ainsi qu’au choix du provides a groundbreaking analysis of section 25 that cadre analytique approprié ou pouvant s’y appliquer. addresses both constitutional questions. Dans l’affaire R. v. Kapp, la Cour d’appel de la The author first reviews the facts of the case, in Colombie-Britannique a arboré une analyse sans which ten non-Aboriginal persons accused of unlawful précédent de l’article 25 qui aborde ces deux questions fishing challenged regulations that restricted fishing in constitutionnelles. an area to members of licensed First Nations bands on En guise d’introduction, l’auteure présente les the ground that they violated section 15 of the Charter. faits de la cause. Dix personnes non autochtones A majority of the British Columbia Court of Appeal accusées d’avoir pêché sans autorisation invoquèrent dismissed the appeal, finding no infringement of l’article 15 de la Charte afin de contester la section 15. -

R. V. Morris: a Shot in the Dark and Its Repercussions

R. v. Morris: A Shot in the Dark and Its Repercussions KERRY WILKINS* ITHE SCOPE OF THE TSARTLIP TREATY RIGHT TO HUNT 4 II THE LEGITIMATE REACH OF PROVINCIAL LEGISLATION 10 Division of Powers: The Limits of Provincial Legislative Authority 11 Interjurisdictional Immunity 11 Shielding Treaty Rights from Provincial Interference 13 Then What Happened: Canadian Western Bank and Lafarge 18 What This Means 23 Section 88 of the Indian Act 26 III SOME CONSEQUENCES 31 IV A FINAL, UNEXPLORED ISSUE 35 VCONCLUSION 37 The Supreme Courts decision in R. v. Morris, [2006] 2 S.C.R. 915, 2006 SCC 59, which upheld and enforced the treaty right of Tsartlip hunters to hunt safely at night with lights, is important for the practical consequences of its somewhat surprising doctrinal pronouncements. By rejecting the assumption that hunting at night is inherently dangerous, it converted what many thought would be an all or nothing issue into a matter for case-by-case Editors Note: This paper was published pursuant to invitation and was not subject to double- blind peer review. The ILJ will invite one author each year to provide commentary on a recent major case, usually a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada. In Volume 6, Number 2, John McEvoy discussed R. v. Sappier; R. v. Gray. We thank Mr. Kerry Wilkins for providing the following comment on R. v. Morris for Volume VII. * Kerry Wilkins is a Toronto lawyer and, in 200809, an adjunct professor at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. Special thanks to Kent McNeil for helpful comments on an earlier draft and for giving me pre-publication access to relevant recent work of his own. -

Court File No.: 35379 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA (ON APPEAL from a JUDGMENT of the COURT of APPEAL for ONTARIO) BETWEEN: AN

Court File No.: 35379 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGMENT OF THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO) BETWEEN: ANDREW KEEWATIN JR. and JOSEPH WILLIAM FOBISTER on their own behalf and on behalf of all other members of GRASSY NARROWS FIRST NATION APPELLANTS (Plaintiffs) -and- MINISTER OF NATURAL RESOURCES and RESOLUTE FP CANADA INC. (formerly ABITIBI-CONSOLIDATED INC.) RESPONDENTS (Defendants) -and- THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENTS (Third Party) -and- LESLIE CAMERON on his own behalf and on behalf of all other members of WABAUSKANG FIRST NATION RESPONDENTS (Interveners) -and- GOLDCORP INC. RESPONDENTS (Intervener) FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF SASKATCHEWAN ANDREW KEEWATIN JR. and JOSEPH WILLIAM FOBISTER on their own behalf and on behalf of all other members of GRASSY NARROWS FIRST NATION APPELLANTS (Plaintiffs) -and- MINISTER OF NATURAL RESOURCES and RESOLUTE FP CANADA INC. (formerly ABITIBI-CONSOLIDATED INC.) RESPONDENTS (Defendants) -and- THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF CANADA RESPONDENTS (Third Party) -and- LESLIE CAMERON on his own behalf and on behalf of all other members of WABAUSKANG FIRST NATION RESPONDENTS (Interveners) -and- GOLDCORP INC. RESPONDENTS (Intervener) R. James Fyfe Lynne Watt Aboriginal Law Branch Gowling Lafleur Henderson LLP Ministry of Justice Barrister’s & Solicitors 820-1874 Scarth Street Suite 2600, 160 Elgin Street REGINA, SK S4P 4B3 OTTAWA, ON K1P 1C3 Tel: (306) 787-7846 Tel: (613)786-8695 Fax: (306) 787-9111 Fax: (613)788-3509 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Intervener, Agent for the Intervener, The Attorney General for Saskatchewan The Attorney General for Saskatchewan Saskatchewan TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PART I OVERVIEW OF ARGUMENT 1 PART II STATEMENT OF ISSUES 1 PART III ARGUMENT 2 A. -

Constitutional Reconciliation and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1 Amy Swi! En*

Constitutional Reconciliation and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1 Amy Swi! en* ) is paper considers the relationship between Ce document examine la relation entre the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and la Charte des droits et libertés et Indigenous self-determination in the context l'autodétermination autochtone dans le of constitutional reconciliation in Canada. contexte de la réconciliation constitutionnelle It begins by reviewing case law and legal au Canada. Il commence par examiner la scholarship on the application of the Charter jurisprudence ainsi que les connaissances to Aboriginal governments, with a particular juridiques relatives à l'application de la focus on the debates over the interpretation Charte aux gouvernements autochtones, en of section 25, which stipulates that Charter accordant une attention particulière aux rights cannot "abrogate or derogate" from débats sur l'interprétation de l'article 25, qui Aboriginal and treaty rights. I show that, stipule que les droits garantis par la Charte ne while di% erent options have been suggested for peuvent " abroger " les droits ancestraux et issus how the Charter could be interpreted in the de traités ou " déroger " à ceux-ci. Je démontre case of a con' ict between Charter rights and que, bien que di% érentes options aient été Aboriginal rights, each of these possibilities suggérées quant à la manière dont la Charte creates problems of its own. Fundamentally, pourrait être interprétée dans le cas d'un con' it the seemingly irresolvable tensions that emerge entre les droits de la Charte et les droits des between the various interpretations of section Autochtones, chacune de ces possibilités crée des 25 re' ect a deeper problem that it is necessary problèmes qui lui sont propres. -

SCC File No. 38734 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA (ON APPEAL from the COURT of APPEAL for BRITISH COLUMBIA)

SCC File No. 38734 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR BRITISH COLUMBIA) BETWEEN: HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN Appellant (Appellant) -and- RICHARD LEE DESAUTEL Respondent (Respondent) FACTUM OF THE APPELLANT, HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN (Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada, SOR /2002-156, as amended) Ministry of Attorney General Borden Ladner Gervais LLP Legal Services Branch World Exchange Plaza 1405 Douglas St., 3rd Floor 1300 – 100 Queen Street Victoria, BC V8W 2G2 Ottawa, ON K1P 1J9 Glen R. Thompson Karen Perron Heather Cochran Tel: 250.387.0417 Tel: 613.369.4795 Fax: 250.387.0343 Fax: 613.230.8842 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Appellant, Ottawa Agent for the Appellant, Her Majesty the Queen Her Majesty the Queen 2 ORIGINAL TO: Registrar Supreme Court of Canada 301 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0J1 COPY TO: Arvay Finlay LLP Gowling WLG (Canada) LLP 1710 - 401 West Georgia Street 2600 - 160 Elgin Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5A1 Ottawa, ON K1P 1C3 Mark G. Underhill Jeffrey W. Beedell Tel: 604.283.2912 Tel: 613.786.0171 Fax: 888.575.3281 Fax: 613.788.3587 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Counsel for the Respondent, Ottawa Agent for the Respondent, Richard Lee Desautel Richard Lee Desautel Attorney General of Ontario Borden Ladner Gervais LLP 720 Bay Street, 8th Floor World Exchange Plaza Toronto, ON M7A 2S9 1300 - 100 Queen Street Ottawa, ON K1P 1J9 Manizeh Fancy Karen Perron Kisha Chatterjee Tel: 613.369.4795 -

Notes for the CBA Talk

The Doctrine of Reconciliation in Chief Justice McLachlin‟s Court Constance MacIntosh Outline 1. Introduction 2. Origin stories: Early differences regarding the meaning of reconciliation, and the judicial role in enabling it. 3. McLachlin‟s Court and reconciliation 3a. Reconciliation and infringement 3b. Reconciliation as a process 4. Unreconciled tensions 5. Reconciliation practices outside of s.35(1) situations 6. Concluding comments 1. Introduction Our current Chief Justice, Beverley McLachlin, was appointed to sit on the bench of the Supreme Court of Canada in 1989. At that time, s.35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, a provision which recognizes and affirms existing aboriginal and treaty rights, was fairly freshly minted. Although “born in the political arena, it was left to the judiciary to flesh out how these rights would be defined and protected.”1 By 1989, the Court had heard arguments on s.35(1), but had not yet delivered its first set of reasons interpreting it.2 The situation was considerably different by the time Beverley McLachlin was appointed Chief Justice, in 2000, as during those eleven years the Court released a number of foundational decisions which interpreted s.35(1) in terms of Aboriginal rights3, title *Associate Professor, Dalhousie Faculty of Law. I would like to thank and acknowledge Michael Asch, John Borrows, Kent McNeil, and Brian Noble for their comments, insights and helpful conversations on earlier drafts of this paper. I would also like to thank Hamar Foster for conversations on aspects of this paper. Errors are, of course, my own. 1 Gordon Christie, “Judicial Justification of Recent Developments in Aboriginal Law” (2002) 17 (2) Can J.L. -

Oakes Test,“Purging” Facebook of Threats and Hate Speech

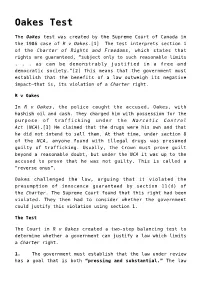

Oakes Test The Oakes test was created by the Supreme Court of Canada in the 1986 case of R v Oakes.[1] The test interprets section 1 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which states that rights are guaranteed, “subject only to such reasonable limits . as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”[2] This means that the government must establish that the benefits of a law outweigh its negative impact—that is, its violation of a Charter right. R v Oakes In R v Oakes, the police caught the accused, Oakes, with hashish oil and cash. They charged him with possession for the purpose of trafficking under theNarcotic Control Act (NCA).[3] He claimed that the drugs were his own and that he did not intend to sell them. At that time, under section 8 of the NCA, anyone found with illegal drugs was presumed guilty of trafficking. Usually, the Crown must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, but under the NCA it was up to the accused to prove that he was not guilty. This is called a “reverse onus”. Oakes challenged the law, arguing that it violated the presumption of innocence guaranteed by section 11(d) of the Charter. The Supreme Court found that this right had been violated. They then had to consider whether the government could justify this violation using section 1. The Test The Court in R v Oakes created a two-step balancing test to determine whether a government can justify a law which limits a Charter right. 1. -

Whither Section 25 of the Charter?

Kahkewistahaw First Nation v Taypotat – Whither Section 25 of the Charter? Jennifer Koshan and Jonnette Watson Hamilton* Introduction responsibilities associated with self-govern- ment.”4 Seen in this light, the election code’s Th e Supreme Court of Canada has to date education requirement might have been treated delivered eight Charter equality decisions in an as a matter to be shielded from scrutiny under Aboriginal context.1 In the most recent case, Kah- section 25 of the Charter, which requires Char- kewistahaw First Nation v Taypotat, the Court ter rights to be interpreted so as not to derogate unanimously dismissed Louis Taypotat’s chal- from Aboriginal, treaty or other rights. However, lenge to his community’s election code require- the Kahkewistahaw First Nation did not make a ment that members of the First Nation running section 25 argument before the Supreme Court.5 for election as Chief or Band Councillor have a Grade 12 education or its equivalent. In fact, the Court has not dealt with sec- tion 25 since R v Kapp in 2008, and then it was Tay potat, aged 76, had previously held offi ce only the concurring judgment of Justice Basta- as Chief for almost thirty years in total, but he rache that fully explored the implications of the was disqualifi ed from running again in 2011 section.6 Given this lack of guidance, it is not because he did not meet the new education surprising that section 25 arguments are being requirement. He had attended residential school omitted in Charter litigation. until he was fourteen, and his education had been subsequently assessed at a Grade 10 level. -

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution

Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution Report of the Expert Panel January 2012 © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 ISBN 978-1-921975-28-8 (print) ISBN 978-1-921975-29-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-921975-30-1 (HTML) Creative Commons licence Except where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution–Non-Commercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au). The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links provided) as is the full legal code for the CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 AU licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/legalcode). This document should be attributed as: Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution: Report of the Expert Panel Disclaimer The material contained in this document has been developed by the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition of Indigenous Australians. The views and opinions expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of or have the endorsement of the Commonwealth Government or of any minister, or indicate the Commonwealth’s commitment to a particular course of action. In addition, the members of the Expert Panel, the Commonwealth Government, and its employees, officers and agents accept no responsibility for any loss or liability (including reasonable legal costs and expenses) incurred or suffered where such loss or liability was caused by the infringement of intellectual property rights, including the moral rights, of any third person, including as a result of the publishing of the submissions.