Donald Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

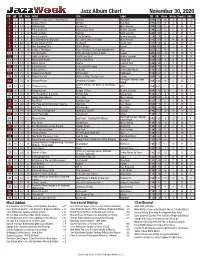

November 30, 2020 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart November 30, 2020 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Artemis 3 weeks at No. 1 / Most Reports Artemis Blue Note 310 291 19 10 51 0 2 2 2 1 Gregory Porter All Rise Blue Note 277 267 10 13 38 0 3 4 13 3 Yellowjackets Jackets XL Mack Avenue 259 236 23 5 49 4 4 7 6 4 Peter Bernstein What Comes Next Smoke Sessions 244 222 22 6 48 0 4 5 4 4 Javon Jackson Deja Vu Solid Jackson 244 235 9 7 47 1 6 6 8 5 Joe Farnsworth Time To Swing Smoke Sessions 229 229 0 9 40 0 7 8 3 1 Christian McBride Big Band For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver Mack Avenue 217 213 4 14 38 0 8 25 40 8 Brandi Disterheft Trio Surfboard Justin Time 211 155 56 3 47 3 9 9 15 9 Alan Broadbent Trio Trio In Motion Savant 209 206 3 5 47 2 10 14 12 10 Isaiah J. Thompson Plays The Music Of Buddy Montgomery WJ3 207 187 20 7 38 1 11 3 5 3 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side of Horace Silver Savant 203 242 -39 10 39 0 12 13 6 3 Eddie Henderson Shuffle and Deal Smoke Sessions 198 192 6 14 35 0 13 12 11 3 Kenny Washington What’s The Hurry Lower 9th 189 194 -5 14 34 1 14 10 13 6 Nubya Garcia Source Concord Jazz 188 199 -11 13 35 1 15 19 17 15 Ella Fitzgerald The Lost Berlin Tapes Verve 185 172 13 6 41 0 16 16 16 15 Chien Chien Lu The Path Chien Chien Music 175 185 -10 8 38 2 17 21 21 17 Uptown Jazz Tentet What’s Next Irabbagast 170 164 6 6 37 1 18 20 26 18 Richard Baratta Music In Film: The Reel Deal Savant 166 170 -4 4 40 1 Provogue / Mascot Label 19 30 78 19 George Benson Weekend in London Group 165 146 19 2 35 7 20 18 19 17 Teodross Avery Harlem Stories: -

Trumpeter Terence Blanchard

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Terence Blanchard PERSON Blanchard, Terence Alternative Names: Terence Blanchard; Life Dates: March 13, 1962- Place of Birth: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Work: New Orleans, LA Occupations: Trumpet Player; Music Composer Biographical Note Jazz trumpeter and composer Terence Oliver Blanchard was born on March 13, 1962 in New Orleans, Louisiana to Wilhelmina and Joseph Oliver Blanchard. Blanchard began playing piano at the age of five, but switched to trumpet three years later. While in high school, he took extracurricular classes at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. From 1980 to 1982, Blanchard studied at Rutgers University in New Jersey and toured with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. In 1982, Blanchard replaced trumpeter Wynton Marsalis in Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, where he served as musical director until 1986. He also co- led a quintet with saxophonist Donald Harrison in the 1980s, recording five albums between 1984 and 1988. In 1991, Blanchard recorded and released his self-titled debut album for Columbia Records, which reached third on the Billboard Jazz Charts. He also composed musical scores for Spike Lee’s films, beginning with 1991’s Jungle Fever, and has written the score for every Spike Lee film since including Malcolm X, Clockers, Summer of Sam, 25th Hour, Inside Man, and Miracle At St. Anna’s. In 2006, he composed the score for Lee's four-hour Hurricane Katrina documentary for HBO entitled When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. Blanchard also composed for other directors, including Leon Ichaso, Ron Shelton, Kasi Lemmons and George Lucas. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Wavelength (April 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 4-1981 Wavelength (April 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (April 1981) 6 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. APRIL 1 981 VOLUME 1 NUMBE'J8. OLE MAN THE RIVER'S LAKE THEATRE APRIL New Orleans Mandeville, La. 6 7 8 9 10 11 T,HE THE THIRD PALACE SUCK'S DIMENSION SOUTH PAW SALOON ROCK N' ROLL Baton Rouge, La. Shreveport. La. New Orleans Lalaye"e, La. 13 14 15 16 17 18 THE OLE MAN SPECTRUM RIVER'S ThibOdaux, La. New Orleans 20 21 22 23 24 25 THE LAST CLUB THIRD HAMMOND PERFORMANCE SAINT DIMENSION SOCIAL CLUB OLE MAN CRt STOPHER'S Baton Rouge, La. Hammond, La. RIVER'S New Orleans New Orleans 27 29 30 1 2 WEST COAST TOUR BEGINS Barry Mendelson presents Features Whalls Success? __________________6 In Concert Jimmy Cliff ____________________., Kid Thomas 12 Deacon John 15 ~ Disc Wars 18 Fri. April 3 Jazz Fest Schedule ---------------~3 6 Pe~er, Paul Departments April "Mary 4 ....-~- ~ 2 Rock 5 Rhylhm & Blues ___________________ 7 Rare Records 8 ~~ 9 ~k~ 1 Las/ Page _ 8 Cover illustration by Rick Spain ......,, Polrick Berry. Edllor, Connie Atkinson. -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

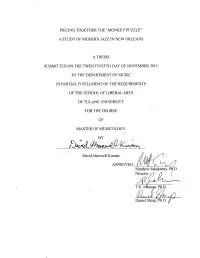

By David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents

Copyright by David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Chapter INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 1. JAZZ AND JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS: A BACKGROUND ................ 3 2. ECONOMICS AND POPULARITY OF MODERN JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS 8 3. MODERN JAZZ RECORDINGS IN NEW ORLEANS …..................... 22 4. ALL FOR ONE RECORDS AND HAROLD BATTISTE: A CASE STUDY …................................................................................................................. 38 CONCLUSION …........................................................................................ 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY ….................................................................................... 50 i 1 Introduction Modern jazz has always been artistically alive and creative in New Orleans, even if it is not as well known or commercially successful as traditional jazz. Both outsiders coming to New Orleans such as Ornette Coleman and Cannonball Adderley and locally born musicians such as Alvin Battiste, Ellis Marsalis, and James Black have contributed to this music. These musicians have influenced later players like Steve Masakowski, Shannon Powell, and Johnny Vidacovich up to more current musicians like Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, and Christian Scott. There are multiple reasons why New Orleans modern jazz has not had a greater profile. Some of these reasons relate to the economic considerations of modern jazz. It is difficult for anyone involved in modern jazz, whether musicians, record -

National Endowment for the Arts Announces 2022 NEA Jazz Masters

July 20, 2021 Contacts: Liz Auclair (NEA), [email protected], 202-682-5744 Marshall Lamm (SFJAZZ), [email protected], 510-928-1410 National Endowment for the Arts Announces 2022 NEA Jazz Masters Recipients to be Honored on March 31, 2022, at SFJAZZ Center in San Francisco Washington, DC—For 40 years, the National Endowment for the Arts has honored individuals for their lifetime contributions to jazz, an art form that continues to expand and find new audiences through the contributions of individuals such as the 2022 NEA Jazz Masters honorees—Stanley Clarke, Billy Hart, Cassandra Wilson, and Donald Harrison Jr., recipient of the 2022 A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy. In addition to receiving a $25,000 award, the recipients will be honored in a concert on Thursday, March 31, 2022, held in collaboration with and produced by SFJAZZ. The 2022 tribute concert will take place at the SFJAZZ Center in San Francisco, California, with free tickets available for the public to reserve in February 2022. The concert will also be live streamed. More details will be available in early 2022. This will be the third year the NEA and SFJAZZ have collaborated on the tribute concert, which in 2020 and 2021 took place virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “The National Endowment for the Arts is proud to celebrate the 40th anniversary of honoring exceptional individuals in jazz with the NEA Jazz Masters class of 2022,” said Ann Eilers, acting chairman for the National Endowment of the Arts. “Jazz continues to play a significant role in American culture thanks to the dedication and artistry of individuals such as these and we look forward to working with SFJAZZ on a concert that will share their music and stories with a wide audience next spring.” Stanley Clarke (Topanga, CA)—Bassist, composer, arranger, producer Clarke’s bass-playing, showing exceptional skill on both acoustic and electric bass, has made him one of the most influential players in modern jazz history. -

Henry Butler Bio Widely Hailed As a Pianist and Vocalist, Henry Butler Is

Henry Butler Bio Widely hailed as a pianist and vocalist, Henry Butler is considered the premier exponent of the great New Orleans jazz and blues piano tradition. A master of musical diversity, he combines the percussive jazz piano playing of McCoy Tyner and the New Orleans style playing of Professor Longhair to craft a sound uniquely his own. A rich amalgam of jazz, Caribbean, classical, pop, blues, and R&B, his music is as excitingly eclectic as that of his New Orleans birthplace. Butler performs as a soloist; with his blues groups—Henry Butler and the Game Band, and Henry Butler and Jambalaya; and with his traditional jazz band, Papa Henry and the Steamin’ Syncopators, as well as with other musicians. In 2013, Butler, Bernstein & The Hot 9 was formed to record Viper’s Drag, released in the summer of 2014 as the first release of the relaunched Impulse! label. His recordings have been noted by Downbeat and Jazz Times, and his performances are regularly reviewed in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, and others. He has appeared on the hit HBO show Treme and is included on the 2012 CD Treme, Season 2: Music from the Original HBO Series. Blinded by glaucoma at birth, Butler was admitted to the Louisiana School for the Blind (now the Louisiana School for the Visually Impaired) in Baton Rouge at the age of five, and cycled back and forth between Baton Rouge during the school year and the Calliope Housing Projects in New Orleans in the summer. Butler may have been born blind, but someone with clearer, deeper, more creative vision would be hard to find. -

Big Chief Donald Harrison Comes to the Big Apple

Big Chief Donald Harrison Comes To The Big Apple New Orleans Jazz Legend To Play NYC's Symphony Space by Tom Pryor April 16, 2012 Longtime Nat Geo Music readers must know by now that we are big, big fans of the HBO Original series Treme, and of the traditional musics and culture of New Orleans in general - especially NOLA's unique Mardi Gras Indian tradition. So it should be no surprise to find out that we were especially excited when we heard that saxman "Big Chief" Donald Harrison was coming to town this month - because Harrison is not only one of NOLA's most versatile and respected jazz artists; and he's not just another recurring, real-life fixture on Treme, but he's an honest-to-goodness "Big Chief" of the Congo Nation Afro- New Orleans Cultural Group - a direct link to the same tradition that brought us everything from the Wild Magnolias to the Dixie Cups. So you know it's gonna be a funky good time - and that the roots will run deep! An Evening with the Big Chief Donald Harrison is scheduled for Friday, April 27th, and New York's venerable Symphony Space, and will include a special guest performance by Grammy Nominated trumpeter Christian Scott. Here's what the official press release had to say about the event: Big Chief Donald Harrison merges the sounds of the New Orleans Jazz Fest and Big Apple Jazz with a special guest performance by Grammy Nominee Christian Scott. Big Chief Donald Harrison merges the sounds of the New Orleans Jazz Fest and Big Apple Jazz with a special guest performance by Grammy Nominee Christian Scott. -

Friends of WWOZ Board of Directors Meeting May 9, 2012 General Manager's Report

Friends of WWOZ Board of Directors Meeting May 9, 2012 General Manager's Report 1. 2012 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival Coverage. Once again, WWOZ provided start-to-finish broadcast and webcast coverage of this year’s New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. And once again, the station’s remote production krewe headed by Program Director Dwayne Breashears and Chief Engineer Damond Jacob provided live feeds to seventeen stations around the country, including KUVO (Denver), KVJZ (Vail), WUSM, Hattiesburg, MS, KPOV, Bend, OR, KDHX, St Louis, MO, CIUT, Toronto, Canada, KFCF, Fresno, CA, WNCU, Durham, NC, WCLK, Atlanta, GA, KMUD, Garberville, CA, KMUE, Eureka ,CA, KLAI, Laytonville/Shelter Cove, CA, WPFW, Washington, DC, KGOU, Norman, OK, KROU Spencer/Oklahoma City, KOUA, Ada, OK, KWOU, Woodward, OK. A small broadcast crew and more than 100 volunteers handled WWOZ’s multiple Jazz Fest activities ranging from broadcast, to membership/brass pass distribution, WWOZ Mango Freeze sales, Piano Night, and night time broadcasts from local clubs. Broadcast Krewe: The broadcast crew included George Ingmire, Bradley Blanchard, Jerry Lenaz, SherriLynn Colby-Bottel, David Kunian, Dimitri Apessos, Linda Santi, Olivia Greene, and many more. Engineering Krewe: The engineering crew included Tony Guillory, Robert Carroll, Khalid Hafiz, and Susan Jacob. Volunteer Power: Veronica Cromwell, Bill Insley, Leslie Cooper, Elsie Bunny Walker, Mary Lambert, Marie MacAdory, Paige Patriarca, Ruth Marinello, Jerry Lenaz, Heather McGlynn, Linz Adams, Mary Naughton, Christy Grimes, Ron Clingenpeel, Lance Albert, Rick Wilkof, Eric Ward, Duane Williams, Melissa Gemeinhardt, Christy Carney, Duane Williams, Betty Schlater, Melissa DeOrazio, Matthew De Orazio, Craig Christopher, Steve Daub, and many more. -

In This Issue

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC In This Issue ab baars Charles Gayle woody herman Coleman Hawkins kidd jordan joe lovano john and bucky pizzarelli lou marini Daniel smith 2012 Critic’s poll berlin jazz fest in photos Volume 39 Number 1 Jan Feb March 2013 SEATTLE’S NONPROFIT earshotCREATIVE JAZZ JAZZORGANIZATION Publications Memberships Education Artist Support One-of-a-kind concerts earshot.org | 206.547.6763 All Photos by Daniel Sheehan Cadence The Independent Journal of Creative Improvised Music ABBREVIATIONS USED January, February, March 2013 IN CADENCE Vol. 39 No. 1 (403) acc: accordion Cadence ISSN01626973 as: alto sax is published quarterly online bari s : baritone sax and annually in print by b: bass Cadence Media LLC, b cl: bass clarinet P.O. Box 13071, Portland, OR 97213 bs: bass sax PH 503-975-5176 bsn: bassoon cel: cello Email: [email protected] cl: clarinet cga: conga www.cadencejazzmagazine.com cnt: cornet d: drums Subscriptions: 1 year: el: electric First Class USA: $65 elec: electronics Outside USA : $70 Eng hn: English horn PDF Link and Annual Print Edition: $50, Outside USA $55 euph: euphonium Coordinating Editor: David Haney flgh: flugelhorn Transcriptions: Colin Haney, Paul Rogers, Rogers Word flt: flute Services Fr hn: French horn Art Director: Alex Haney g: guitar Promotion and Publicity: Zim Tarro hca: harmonica Advisory Committee: kybd: keyboards Jeanette Stewart ldr: leader Colin Haney ob: oboe Robert D. Rusch org: organ perc: percussion p: piano ALL FOREIGN PAYMENTS: Visa, Mastercard, Pay Pal, and pic: piccolo Discover accepted. rds: reeds POSTMASTER: Send address change to Cadence Magazine, P.O.