The Landscape's Rock Foundations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorials of Old Wiltshire I

M-L Gc 942.3101 D84m 1304191 GENEALOGY COLLECTION I 3 1833 00676 4861 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldwiOOdryd '^: Memorials OF Old Wiltshire I ^ .MEMORIALS DF OLD WILTSHIRE EDITED BY ALICE DRYDEN Editor of Meinoriah cf Old Northamptonshire ' With many Illustrations 1304191 PREFACE THE Series of the Memorials of the Counties of England is now so well known that a preface seems unnecessary to introduce the contributed papers, which have all been specially written for the book. It only remains for the Editor to gratefully thank the contributors for their most kind and voluntary assistance. Her thanks are also due to Lady Antrobus for kindly lending some blocks from her Guide to Amesbury and Stonekenge, and for allowing the reproduction of some of Miss C. Miles' unique photographs ; and to Mr. Sidney Brakspear, Mr. Britten, and Mr. Witcomb, for the loan of their photographs. Alice Dryden. CONTENTS Page Historic Wiltshire By M. Edwards I Three Notable Houses By J. Alfred Gotch, F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A. Prehistoric Circles By Sir Alexander Muir Mackenzie, Bart. 29 Lacock Abbey .... By the Rev. W. G. Clark- Maxwell, F.S.A. Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers . By H. St. George Gray The Rising in the West, 1655 . The Royal Forests of Wiltshire and Cranborne Chase The Arundells of Wardour Salisbury PoHtics in the Reign of Queen Anne William Beckford of Fonthill Marlborough in Olden Times Malmesbury Literary Associations . Clarendon, the Historian . Salisbury .... CONTENTS Page Some Old Houses By the late Thomas Garner 197 Bradford-on-Avon By Alice Dryden 210 Ancient Barns in Wiltshire By Percy Mundy . -

December 2020

Mercia Rocks OUGS West Midlands Branch Newsletter Issue No 4 December 2020 High Tor Limestone Reef, Matlock, Derbyshire. Jun 2015 - Mike Hermolle Branch Officers Contents Branch Organiser – David Green Branch Treasurer - Susan Jackson Branch Organiser’s report p 2 Newsletter Editor – Mike Hermolle Message on events p 2 AGM 2021 p 3 Branch Committee Quiz p 4 Emma Askew Summary of a research topic p 6 Sandra Morgan Local Geology p 9 Alan Richardson Geo-etymology p 11 Adrian Wyatt Other Societies P 14 Stop Press p 15 If you would like to join the Online Talks p 16 committee please do get in touch 2020 AGM Draft Minutes p 17 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Branch Organiser’s Report This year has been a year we may be remembering for quite a while, unfortunately the Branch has not been able to organise any events this year and is not likely we will be able to have any events until the lock down restrictions are lifted. You will see in this newsletter that the AGM will be held virtually via Zoom this time. The meeting is being held in February and I hope by then we may have some better news regarding what events we may be able to hold next year. I would be very happy to try to help anyone who would like to join the AGM meeting but is unsure of using ZOOM. It is easy to use to join in meetings and is not that hard if anyone is unsure. We will not be having a speaker this year so it will only take up an hour or so of your time. -

Community and Stakeholder Consultation (2018)

Community and Stakeholder Consultation (2018) Forming part of the South Worcestershire Open Space Assessment and Community Buildings and Halls Report (FINAL MAY 2019) 1 | P a g e South Worcestershire Open Space Assessment - Consultation Report Contents Section Title Page 1.0 Introduction 4 1.1 Study overview 4 1.2 The Community and Stakeholder Needs Assessment 5 2.0 General Community Consultation 7 2.1 Household survey 7 2.2 Public Health 21 2.3 Key Findings 26 3.0 Neighbouring Local Authorities and Town/Parish Councils/Forum 29 3.1 Introduction 29 3.2 Neighbouring Authorities – cross boundary issues 29 3.3 Town/Parish Councils 34 3.4 Worcester City Council – Ward Members 45 3.5 Key Findings 47 4.0 Parks, Green Spaces, Countryside, and Rights of Way 49 4.1 Introduction 49 4.2 Review of local authority policy and strategy 49 4.3 Key Stakeholders - strategic context and overview 55 4.4 Community Organisations Survey 60 4.5 Parks and Recreation Grounds 65 4.6 Allotment Provision 68 4.7 Natural Green Space, Wildlife Areas and Woodlands 70 4.8 Footpaths, Bridleways and Cycling 75 4.9 Water Recreation 80 4.10 Other informal amenity open space 82 4.11 Outdoor recreation in areas of sensitivity and biodiversity 83 4.12 Other comments and observations 89 4.13 Key Findings 90 5.0 Play and Youth facility provision 93 5.1 Review of Policy and Strategy 93 5.2 Youth and Play facilities – Stakeholders 97 5.3 Key Findings 102 6.0 Concluding remarks 104 2 | P a g e Glossary of Terms Term Meaning ACRE Action with Communities in Rural England ANGSt Accessible -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Donhead St. Andrew - Census 1851

Donhead St. Andrew - Census 1851 9 4 8 /1 Year 7 Address Surname Given Names Position Status Age Sex Occupation Place of Birth Notes 0 1 Born O H 1 Lower Street Kember William Head M 38 M 1813 Gardener, Servant Tollard Royal Page 1. Folio 50 ed4a Kember Patience Wife M 33 F 1818 Semley Kember Jane Daur U 15 F 1836 Scholar Shaftesbury; Dorset Kember Charles Son 11 M 1840 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Kember William Son 10 M 1841 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Kember Keziah Daur 8 F 1843 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Kember Mary A. Daur 6 F 1845 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Kember George Son 5 M 1846 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Kember Albert Son 2 M 1849 Donhead St Andrew 2 Lower Street Shipman John Head M 23 M 1828 Journeyman Smith Baverstock Shipman Mary Wife M 24 F 1827 Donhead St Mary Shipman Eleanor Daur 2 F 1849 Donhead St Andrew Shipman Harriett A. Daur 0 F 1851 Donhead St Andrew Age 4mths 0 House Uninhabited 3 Lower Street Dewey William Head M 48 M 1803 Farrier Donhead St Andrew Dewey Ann Wife M 50 F 1801 Donhead St Mary Dewey Ellen Daur U 20 F 1831 Dress Maker Winchester Dewey James Son U 18 M 1833 Farrier's son Winchester Dewey George Son 16 M 1835 Farrier's son Donhead St Andrew Dewey Saml. Son 14 M 1837 Farrier's son Donhead St Andrew Dewey Hugh Son U 12 M 1839 Farrier's son Donhead St Andrew Page 2 Dewey Sidney Son 10 M 1841 Scholar Donhead St Andrew Dewey Martha E. -

Alfrick and the Suckley Hills 5 Mile Circular Geology & Landscape Trail 5

Rocks along the trail The Abberley and Malvern Hills Geopark .... ....is one of a new generation of landscape designations Sedimentary rocks are made up of particles deposited that have been created specifically for the interest of the in layers. They usually form on the sea floor, in lakes and rivers, or in deserts. The sediment layers are compacted geology and scenery within a particular area. and consolidated by the weight of overlying material. www.Geopark.org.uk circular trail The particles within the layers can also be cemented together by minerals (e.g. iron) carried by water percolating through the sediments. Eventually, over The Geopark Way .... Alfrick and the Suckley Hills millions of years, the compressed sediments become rock. ....winds its way for 109 miles through the Abberley and Alfrick and the Suckley Hills Malvern Hills Geopark from Bridgnorth to Gloucester. The Sedimentary rocks today are being formed over much of the Earth’s surface. Geopark Way passes through delightful countryside as it explores 700 million years of the Earth’s history. Limestone is composed primarily of the mineral calcite. Limestones are very variable rocks. The Geopark Way Circular Trails ... fossil rich limestone seen along ....form a series of walking trails that each incorporate a the trail was deposited in a warm shallow sea where shell fragments segment of the Geopark Way linear long distance trail. from millions of dead creatures fell to the bottom of the sea and accumulated to great thicknesses. The walk has been Shale is composed of millions of researched and written by tiny fragments of material. -

Sutton Mandeville

Foot and Mouth Disease Sutton Mandeville FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, the 13th July, 1872 :- Police Divisions of Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, Cottles, ……Hindon – Brixton Deverill, Donhead St. Mary, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Bishop, Kingston Deverill, Monkton Deverill, Mere, Sutton Mandeville, Wardour, West Knoyle, West Tisbury. Malmesbury – Ashton Keynes, Ashley………… (Salisbury and Winchester Journal - Saturday 20 July, 1872) A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, 3rd August, 1872 :- POLICE DIVISIONS PARISHES Foot and Mouth Disease Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, …….. Chippenham – Alderton, Avon, ………… Devizes – Beechingstoke, Bishop’s Cannings, …………. Hindon - Brixton Deverill, Donhead St. Mary, Dinton, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Bishop, Kingston Deverill, Monkton Deverill, Mere, Sedgehill, Semley, Stourton, Sutton Mandeville, Teffont Magna, Upper Pertwood, West Tisbury, West Knoyle, Wardour. ……….. (Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette - Thursday 8 August, 1872) ©Wiltshire OPC Project/Cathy Sedgwick/2013 A return of parishes and places in the county of Wilts in which contagious or infectious disease exists among animals for the week ending Saturday, 21st September, 1872 :- POLICE DIVISIONS PARISHES Foot and Mouth Disease Bradford and Trowbridge – Bradford-on-Avon, Broughton Gifford, …….. Chippenham – Alderton, Bremhill, ………… Devizes – Allcannings, …………. Hindon – Ansty, Brixton Deverill, Compton Chamberlayne, Dinton, Donhead St. Andrew, Ebbesborne, East Knoyle, East Tisbury, Fonthill Gifford, Kingston Deverill, Mere, Semley, Sutton Mandeville, Wardour, West Knoyle, West Tisbury. -

Kellys Directory Extract 1915 Mere

Kellys Directory Extract 1915 Mere MERE is a union town and parish on the borders of three counties – Wilts, Dorset and Somerset – which meet in the vicinity, and is on the road from Salisbury to Taunton Dean, 4 miles north from Gillingham station on the Salisbury to Yeovil branch of the South Western railway, 23 west-by-north from Salisbury, 7 west from Hindon, 7 east-by-north from Wincanton and 102 from London, in the Southern division of the county, Mere hundred, Tisbury and Mere Petty Sessional division, county court district of Shaftesbury, Wylye rural deanery (Heytesbury portion), archdeaconry of Sarum and diocese of Salisbury. The town is lighted with gas from works erected in 1866. The water supply for the whole district is provided by the Rural District Council. The church of St Michael the Archangel is a building of stone in the Perpendicular style, with traces of Early English and reputed Saxon work, consisting of chancel with chapels, clerestoried nave of five bays, aisles, north and south porches, over each of which is a parvise, and a western tower 100 feet high, with pinnacles, and containing a clock with chimes and 8 bells: the chancel is separated from the nave by a beautifully carved oak screen, the upper part of which has been restored at the cost of Mrs A Morrison: there are two chantry chapels, and in the south chapel is a brass to John Betteshorne, d.1398: the present chancel and the chapels were built in the 14th century, but the tower dates from about the middle of the 15th century: there are 580 sittings: in 1883 the churchyard was leveled and planted with shrubs and flowers. -

Grwalks Gloucestershire

GRWalks Gloucestershire Available each March, July and November Ramblers’ Walks Visitors are very welcome to come on up to three March to June 2014 walks listed here before deciding whether they wish to join the Ramblers. DOGS Except for Forest of Dean Group (see below) Only Registered Assistance Dogs are allowed. GRWalks combines full walk details of all the nine Cirencester Group Meet at The Waterloo CP - SP 026021 to Ramblers' groups active in Gloucestershire. One of the share transport. For day walks bring a packed lunch unless advantages of becoming a member of the Ramblers is that you otherwise indicated. See the programme at can walk with any group in Britain at any time. www.ramblers.co.uk/programmes/online.php?group=GR01 IMPORTANT LATE CHANGES will be shown on the www.cirencesterramblers.btck.co.uk link for GRWalks Updates on the Walks Page www.gloucestershireramblers.org.uk/grwalks – do check Cleeve Group Walks start at map reference. See www.ramblers.co.uk/programmes/online.php?group=GR05 or ring the leader if you are not on computer - before travelling. www.cleeveramblers.org.uk Online users can click the top links opposite to look at a group's walks. Click on the title of a walk you are interested in Forest of Dean Group These walks start at the map and scroll down to see an interactive map. We hope lots of reference. Walks may have well-behaved dogs with walkers will be able to see this programme uploaded at permission from leader in advance. See the programme at www.gloucestershireramblers.org.uk/grwalks www.ramblers.co.uk/programmes/online.php?group=GR02 www.fodramblers.org.uk If you need a printed copy of GRWalks write to the editor Mike Garner (GRWalks), Southcot, The Headlands, Gloucester Group Meet centrally at one of two sites as Stroud GL5 5PS. -

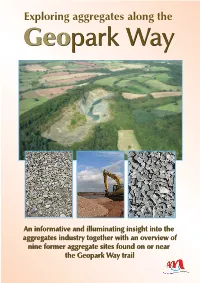

Exploring Aggregates Along The

Exploring aggregates along the An informative and illuminating insight into the aggregates industry together with an overview of nine former aggregate sites found on or near the Geopark Way trail Acknowledgements This booklet has been produced with contributions from Gloucestershire Geology Trust and with input from a number of volunteers, community groups and individuals living near the Geopark Way trail. Volunteers and other interested parties visiting a former aggregate quarry which was last worked in 1992. Astley and Dunley parish, Worcestershire Published by Herefordshire and Worcestershire Earth Heritage Trust Geological Records Centre University of Worcester Henwick Grove Worcester. WR2 6AJ. Tel: 01905 855184 Email: [email protected] Website: www.EarthHeritageTrust.org © Herefordshire and Worcestershire Earth Heritage Trust 2011 Contents Introduction to the aggregate industry 1 The global picture 3 The UK picture 4 How aggregates are used in the UK 6 Problems associated with extraction 9 Positive aspects of extraction 11 Aggregates and the Abberley and Malvern Hills Geopark 13 Malvern Hills Quarries/Chase End Quarry 15 Martley Pit 23 Huntley Quarry 26 Penny Hill Quarry 30 Whitman’s Hill Quarry 33 Callow Hill Quarry 37 Raggits Hill Quarry 40 Eardington Sand and Gravel 42 Hartlebury Common Gravel Pits 44 Publications and trail guides that incorporate aggregate sites within the Abberley and Malvern Hills Geopark 48 Introduction Imagine a world without aggregates. Would it look so different from the one we live in? Would it be a better place? In truth such a world could not exist, as humans have been extracting and using aggregates for many thousands of years. -

Landscape Caves

Caves ue Landscape How partnership working ss Wallpaper riches are ensures underground I rescued from stately treasures are monitored 32 home’s outbuilding Summer 2009 Making rocks matter to people On other pages Outcrops – pp 3-7 Geodiversity is fundamentally important to managing nearly all aspects of the environment, so why do geoconservationists often feel that it is massively undervalued? The truth is that many people are simply unaware of what Geodiversity Cave conservation: Out of sight – is and why it is so important. Tell them that Geodiversity supports many of the basic but not out of mind – p8 functions of life and holds the clues to evolution and our place in the Universe, and interest grows. Explain how their personal history and culture are inextricably linked with the rocks and landscapes around them, and the importance and relevance of Landscapes Geodiversity start to come into sharp focus. rescued from a shed We probably have ourselves to blame for this. All too often we shroud our subject in – p10 jargon and fail to make the all-important links with lifestyle, culture and landscape. This issue of Earth Heritage shows we are, hopefully, getting wise and adopting a more holistic approach. Many of our features emphasise how our cultural development and history are inextricably linked with Geodiversity. John Gordon and Vanessa Kirkbride start a two-part series on the huge influence that the Scottish Opening new landscape and its geology have exerted on cultural and creative efforts over the doors: centuries. We also take a fly-on-the-wall look at some restored Chinese wallpapers Geodiversity which give a fascinating insight to the spectacular karst landscapes, lifestyles and and the cultures which have figured in Chinese painting for over 2,000 years. -

326 August 2106

Maiden Bradley Parish News No 326 August 2016 All Saint’s Flower Festival - Winner of the Visitors’ Choice Royal Ascot by Sue Priestner Editorial I hope that you are enjoying the warm summer weather as much as I am especially as it is only 5 months to Christmas. Schools are now on their summer recess and families will be going on holiday. If like us, you are travelling by car, do make sure that your car has a current MOT certificate. Dates for insurance, tax and MOT rarely coincide and don’t get caught out like we did, on the side of the French motorway, a car without power. The petrol pump decided to die as I was overtaking a lorry with several cars following me – I managed to switch on the hazard warning lights and drifted behind the lorry onto the hard shoulder, and stop. Recovery was excellent, spare parts available and in three days our wheels were restored to us. Despite pay- ing our tax and insurance, our MOT had already run out leaving us without cover – all now rectified. Since last month, we have a new Prime Minister and Cabinet with a mandate to take us out of the European Union. Whichever way you voted, I am sure that you would agree with me in not envying Boris Johnson and his team in trying to unravel over 40 years of trade agreements, production directives and laws, and produce an improved trading platform for our industries without damaging the economy. Each year that goes by there are local individuals who spend time quietly working voluntarily, in support of this village.