Graco Oral History Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

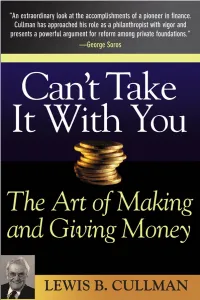

BUSINESSMAN Can't Take It with You the Art of Making and Giving

ffirs.qxd 2/25/04 9:36 AM Page i Praise for Can’t Take It with You “Lewis Cullman is one of this nation’s major and most generous philanthro- pists. Here he combines a fascinating autobiography of a life in finance with a powerful exposé of how the business of giving works, including some tips for all of us on how to leverage our money to enlarge our largess.” —Walter Cronkite “Lewis Cullman has woven a rich and seamless fabric from the varied strands of his business, philanthropic, and personal life. Every chapter is filled with wonderful insights and amusing anecdotes that illuminate a life that has been very well lived. This book has been written with an honesty and candor that should serve as a model for others.” —David Rockefeller “An extraordinary look at the accomplishments of a pioneer in finance. Cullman has approached his role as a philanthropist with vigor and presents a powerful argument for reform among private foundations.” —George Soros Chairman, Soros Fund Management “I was so enjoyably exhausted after reading the book—I can only imagine liv- ing the life! It seems there is no good cause that Lewis has not supported, no good business opportunity that Lewis has missed, and no fun that Lewis has not had.” —Agnes Gund President Emerita, The Museum of Modern Art “Now I know that venture capitalism and horse trading are almost as much fun as looking for new species in the Amazon. This book is exceptionally well written. The prose is evocative, vibrant, and inspirational.” —Edward O. -

Cheerleader Gives up NFL for Her Faith Sumter’S Kristan Ware Says Christianity, Virginity Made Her a Target

S.C. prison chief faces Senate Subcommittee A6 Carolina Backcountry Springtime on Saturday Learn about weaving, blacksmithing, SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 18th-century weaponry and more A2 FRIDAY, MAY 11, 2018 75 CENTS Cheerleader gives up NFL for her faith Sumter’s Kristan Ware says Christianity, virginity made her a target BY ADRIENNE SARVIS home in dance studios. versation because she did not have [email protected] Along with her love for dance and one of her own. cheerleading, Ware has even more When asked why she didn't have a Faith is something that a lot of peo- passion for Christ. playlist, Ware decided to answer hon- ple carry with them everywhere they But, while being on the Miami Dol- estly and told her teammates she is go, including a former Miami Dol- phins cheerleading team gave her the waiting until marriage. phins cheerleader who was allegedly opportunity to do what she loved, the And though her teammates did not singled out for refusing to take God job later caused her distress. seem to mind her personal decision, out of her life for the sake of the Ware said her troubles began after she said the team staff made it a topic team. a trip to London in 2015 during her of discussion during Ware’s audition Though she moved a lot growing up second year with the Dolphins when for next season. in a military family, 27-year-old other cheerleaders were discussing Ware was baptized on April 10, Kristan Ann Ware of Sumter was their sex playlists. -

Mcdonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1994 Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985 Kathleen D. Toerpe Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Toerpe, Kathleen D., "Small Fry, Big Spender: McDonald's and the Rise of a Children's Consumer Culture, 1955-1985" (1994). Dissertations. 3457. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3457 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Kathleen D. Toerpe LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMALL FRY, BIG SPENDER: MCDONALD'S AND THE RISE OF A CHILDREN'S CONSUMER CULTURE, 1955-1985 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY KATHLEEN D. TOERPE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY, 1994 Copyright by Kathleen D. Toerpe, 1994 All rights reserved ) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank McDonald's Corporation for permitting me research access to their archives, to an extent wider than originally anticipated. Particularly, I thank McDonald's Archivist, Helen Farrell, not only for sorting through the material with me, but also for her candid insight in discussing McDonald's past. My Director, Lew Erenberg, and my Committee members, Susan Hirsch and Pat Mooney-Melvin, have helped to shape the project from its inception and, throughout, have challenged me to hone my interpretation of McDonald's role in American culture. -

Great Northern Monthly Salaried Employees Newsletter, 1962

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Great Northern Paper Company Records Manuscripts 1962 Great Northern Monthly Salaried Employees Newsletter, 1962 Great Northern Paper Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/great_northern Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the United States History Commons This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Northern Paper Company Records by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume I No. 10 Great northern newsletter COMPANY FOR MONTHLY SALARIED EMPLOYEES MILLINOCKET, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 28, 1962 Outward signs of Christmas were more than usually evident at the mills this year. Evergreen decorations with myriad colored lights were located on all sides. With the opportunity of adding the beautiful Engineering and Research Building to the sites decorated, the Safety Supervisors, who arranged this program, made the Christmas Spirit visible in tasteful brightness. To spread the spirit of Christmas, the Company forwarded some of Maine’s beautiful evergreen trees, for use as Christmas trees, to Mr. Fred Wachs, President, Lexington Herald-Leader; Mr. Edwin Young, General Manager, Providence Journal; and to Mr. Frank Morrison, President, Pittsburgh Press. Practically all Woodlands work sites were closed December 24 and 25 for the holidays. Employees will work the following Saturday to make up time lost on Monday. This action gave the employees a four- day week end which meant a great deal to men whose work keeps them away from home all week. -

Ad” Medium of Washington—Serving Thousands of People ...' Sunday, —1--- HELP (Conf.)

Classified Ads Classified Ads Branches the City Brandies Throughout the City Throughout -— —-- .>- FOURTEEN PAGES. WASHINGTON, I)., C.? JANUARY 12, 1947 Th$ Star, Evening and Is the Great "Want Ad” Medium of Washington—Serving Thousands of People ...' Sunday, —1--- HELP (Conf.). HELP MEN. HELP MEN. HELP MIN. WOMEN, HELP MEN. _ HELP MEN (Con*.). HELP MEN. and BEAUTICIANS—Can you? Do you smiled SERVICE STATION ATTENDANT, OI pre- THE MAN WE WANT Is between 25 In HAN. white, to solicit appointments for REAL ESTATE and business broker wants Permanent position, A-l, 5'/, days, per- ARCHITECTURAL.—Five draftsmen, full] DISHWASHER, day or night. Apply ferred, for salesman In one of Washing- 38 Tears old. preferably married, he is de- DELICATESSEN, 1101 children’s portraits; 6-day wk., good pay. salesman, with car. Must be willing himself sona! interviews. 8425 Oa. are., 8H. experienced on large buildings, required U person, BALTIMORE Experience not ton’s largest stations; opportunity for alert sirous of building a business for Park rd. n.’e. on Monday. Phone TE. 2455 all day Sunday, MB. worker. Commission good. is a 2001; Sun, and eves.. SH. 8971. —12 I Shepherd Pharmacy supplement present force; extensive pro- Bladensburg Closed or month; and has not yet found himself, he sandwiches, BAILEY. necessary. A. R. SEEL YE, 1400 L st. maKtto earn $175 more per OPERATOR, experienced: 5-day gram of work; 614-day, 40-hr. wk.: new DELICATESSEN MAN, exp. no worker, fine character and willing to put BBAtmr 7723 Are. N.W. delica- HAN, 946. 6-DAY WK.—Rapid raises, exc. -

Oral History Interview with George M. Ryan

An Interview with GEORGE M. RYAN OH 253 Conducted by Arthur L. Norberg on 10-11 June 1993 Los Angeles, CA Charles Babbage Institute Center for the History of Information Processing University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Copyright, Charles Babbage Institute 1 George M. Ryan Interview 10-11 June 1993 Abstract After briefly describing his background and education, Ryan, former chairman and CEO of CADO Systems Corporation, discusses his work in the development and distribution of data processing equipment from the early 1950s through the early 1990s. He recalls work with Benson-Lehner in the early 1950s and he describes the firm's development of the computyper, a billing machine. Ryan discusses his role in the sale of the computyper to Friden and his employment by Friden. He recalls his frustration with Friden's attempts at further development of the product, his involvement in the acquisition of the Flexowriter for Friden, and his management of a branch for Friden in Los Angeles. Ryan recalls his return to Benson-Lehner from Friden in the late 1950s and the events leading to his formation of Intercontinental Systems Incorporated with Pete Taylor in the late 1960s. Ryan describes ISI's distribution and development of data processing equipment and his philosophy for the management of engineering and sales at ISI. Ryan recalls his idea to develop a computer for small businesses and describes his role in the partnership that became CADO Systems Corporation in 1976. He discusses the development of the computer by Jim Ferguson and Bob Thorne, his strategy of marketing the computer to small businesses and government offices, CADO's rapid growth, and the creation of additional product lines. -

Election Bid to Proposals on Tuesday's Ballot

i Clinton County News S^JUtfrih&(Uud0n*<fauL$uv& 1856 117th year .ST. JOHNS,MICHIGAN" . t ^ , , 52 Pages 15 cents 3 a- Voters visit polls Tuesday incumbent ' commissioners, considered a "court of record" and ST. JOHNS-The presidential race Republicans Maurice Gove and Robert therefore six-member juries are ac W has captured the bulk of headline space Montgomery, have competition from ceptable. most of the summer but Tuesday in within their own party during the Also, two townships will have local Clinton County the big political news primary.' Gove's re-election bid to proposals on Tuesday's ballot. Voters in focuses on a four-man race for sheriff represent the western portion of St. Eagle Township will be asked to ap and several commissioner contests. Johns and Bingham Township is op prove 2.7 mills for one year to match Voters will pick the new Clinton posed by Bruce Lanterman. Matched funds planned to construct a bridge o County Sheriff from among the four against Montgomery who presently over Looking Glass River on Hinman Republican candidates on Tuesday's represents the district covering Eagle Rd. In Watertown Township, voters are 'I ballot. No Democrats are seeking the and Watertown Townships are fellow being asked to approve three mills for office and the present Sheriff, Percy Republicans Richard Noble and Dyle three years to improve roads within Patterson, is retiring after 25 years of Henning. their townships. service to the county. Sheriff candidates include: Tony Hufnagel, Clinton County Undersheriff; THE RACE for a seat being vacated Who votes Larry Floate, Clinton County Sheriff's by Robert Ditmer who is seeking a state Deputy; Bruce Angell, DeWitt office involves two Republicans, Township Police Chief; and Ray Donald Gilson and Jeanne Rand. -

Dou1 2013 10 18.Pdf

ISSN 1677-7042 Ano CL No- 203 Brasília - DF, sexta-feira, 18 de outubro de 2013 INTDO.(A/S) : ASSEMBLÉIA LEGISLATIVA DO ESTADO IV - centro de documentação - instituição que reúne documen- Sumário DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE tos de tipologias e origens diversas, sob a forma de originais ou cópias, . A D V. ( A / S ) : ESEQUIAS PEGADO CORTEZ NETO E OU- TRO(A/S) ou referências sobre uma área específica da atividade humana, que não PÁGINA apresente as características previstas nos incisos IX e X do caput; Atos do Poder Judiciário .................................................................... 1 Decisão: O Tribunal, por unanimidade e nos termos do voto V - coleção visitável - conjuntos de bens culturais con- Atos do Poder Executivo.................................................................... 1 do Relator, Ministro Joaquim Barbosa (Presidente), julgou procedente servados por pessoa física ou jurídica que não apresentem as ca- Presidência da República.................................................................... 6 a ação direta. Ausentes, justificadamente, o Ministro Celso de Mello e, racterísticas previstas nos incisos IX e X do caput, e que sejam Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento ...................... 9 neste julgamento, o Ministro Gilmar Mendes. Plenário, 23.05.2013. abertos à visitação, ainda que esporadicamente; EMENTA: CONSTITUCIONAL. COMPETÊNCIA LE- Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação.................................. 9 GISLATIVA. PACTO FEDERATIVO. VIOLAÇÃO. HIPÓTESE VI - degradação - dano de natureza -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

Annual Report of the Department of Education

\-' Public Document No. 2 SIIjF Cl0mmntttu?altl| of Mum^t^mtttB ASS. 3CS„ 3LL, ANNUAL REPORT OF THB Department of Education For the Year ending November 30, 1937 Issued in Accordance with Section 2 of Chapter 69 OF THE General Laws Part I PtJBLICATION OF THIS DOCUMENT APPROVED BY THE COMMISSION ON ADMINISTEATION AND FINANCE 1500. 5-'38. Order 3963. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION JAMES G. REARDON, Commissioner of Education Members of Advisory Board Ex officio The Commissioner of Education, Chairman Term Expires 1938. Mrs. Anna M. Power, 15 Ashland Street, Worcester 1938. Kathryn a. Doyle, 99 Armour Street, New Bedford 1939. P. A. O'Connell, 155 Tremont Street, Boston 1939. Roger L. Putnam, 132 Birnie Avenue, Springfield 1940. Alexander Brin, 319 Tappan Street, Brookline 1940. Thomas H. Sullivan, Slater Building, Worcester George H. Varney, Business Agent Division of Elementary and Secondary Education and State Teachers Colleges PATRICK J. SULLIVAN, Director Supervisors Florence I. Gay, Supervisor of Elementary Education Alfred R. Mack, Superirisor of Secondary Education Raymond A. FitzGerald, Supervisor of Educational Research and Statistics and In- terpreter of School Low Thomas A. Phelan, Supervisor in Education of Teacher Placement Raymond H. Grayson, Supervisor of Physical Education Martina McDonald, Supervisor in Education Ralph H. Colson, Assistant Supervisor in Education Ina M. Curley, Supervisor in Education Philip G. Cashman, Supervisor in Education Presidents op State Teachers Colleges and the Massachusetts School of Art John J. Kelly, Bridgewater James Dugan, Lowell Charles M. Herlihy, Fitchburg Grover C. Boavman, North Adams Martin F. O'Connor, Framingham Edward A. Sullivan, Salem Herbert H. Howes, Hyannis Charles Russell, Westfield William B. -

Great Northern Newsletter for Management Employees, 1968

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Great Northern Paper Company Records Manuscripts 1968 Great Northern Newsletter for Management Employees, 1968 Great Northern Paper Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/great_northern Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Great Northern Paper Company, "Great Northern Newsletter for Management Employees, 1968" (1968). Great Northern Paper Company Records. 93. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/great_northern/93 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Northern Paper Company Records by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GREAT NORTHERN PAPER COMPANY NEWSLETTER FOR MANAGEMENT EMPLOYEES Volume VII No. 9 MILLINOCKET, MAINE Friday, December 20, 1968 1968 director join Great Northern Gives Land In Great Northern Closes Some Roads Allagash. Peter S. Paine, to Snow Sleds. Management con Chairman and Chief Executive cerned for the safety of operators Officer, announced Friday, November and passengers of snow-travelling 22, that the Company will give vehicles has prompted the Company to the people of Maine 700 acres to close some of its roads to the of lake and river frontage in the motorized sleds. Allagash River Valley to be Effective December 16, the follow included in the Allagash Wilderness ing roads will be closed Monday Waterway. (Cont. pg. 2, col. 1) through Saturday: (Cont. pg. 2, col. The land gift will include Ripogenus Dam Road to Sourdna 207 acres in Township 15, Range 14 hunk Lake, New Harrington Lake near the northern extremity of the Road to Telos Lake, Pittston to waterway park, including Allagash Seboomook and Caucomgomoc Roads, Falls and 563 acres along the south the North Branch Road, the Johnson shore of Allagash Lake in Township Pond and Church Pond Roads west of 7, Range 14. -

Barnes Hospital Bulletin

-yf*^ SHELVED IN AKU $ v) .} Barnes Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo. hoSDJTAl_ _■ limp IQfiQ Raymond E. Rowland Elected Board Chairman Raymond E. Rowland was elected chairman of district sales manager and in 1934 became a the Barnes Hospital Board of Trustees at the division assistant sales manager. board's annual meeting Wednesday, April 23. Mr. Rowland was made manager of the Circle- Mr. Rowland succeeds Robert W. Otto, who was ville, Ohio plant in 1934. In 1940, he became a elected to fill the unexpired term of Edgar M. Ralston Purina assistant vice president; in 1943, Queeny, who died July 7, 1968. a vice president. Mr. Rowland became president Mr. Rowland, who has been a member of the of the company in June, 1956, and was named Barnes board for seven years, is former presi- chairman of the board in 1963. On Jan. 1, 1968, dent and chairman of the board for Ralston he retired from the company. Purina Co. For the past year he has served as The new Barnes chairman is also a director of general chairman of the Barnes Hospital Fund. Ralston Purina Co., Mercantile Trust Company Other new officers of the board of trustees in- National Association, Transit Casualty Company, clude Edwin M. Clark, who was re-elected vice Granite City Steel Company, Union Electric Com- chairman, and Irving Edison, selected as vice pany, and Norfolk and Western Railway Company. chairman and treasurer. John Warmbrodt, In addition to Barnes Hospital, Mr. Rowland also Barnes' deputy director, was named secretary. is active in the Herbert Hoover Boys' Club of St.