Arms Procurement Decision Making Volume I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

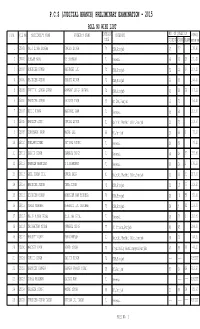

P.C.S (Judicial Branch) Preliminary Examination - 2015 Roll No Wise List S.No

P.C.S (JUDICIAL BRANCH) PRELIMINARY EXAMINATION - 2015 ROLL NO WISE LIST S.NO. ROLL NO CANDIDATE'S NAME FATHER'S NAME CATEGORY CATEGORY NO. OF QUESTION MARKS CODE CORRECT WRONG BLANK (OUT OF 500) 1 25001 NAIB SINGH SANGHA GURDEV SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 48 77 130.40 2 25002 NEELAM RANI OM PARKASH 71 General 45 61 19 131.20 3 25003 AMNINDER KUMAR KASHMIRI LAL 72 ESM,Punjab 32 26 67 107.20 4 25004 RAJINDER SINGH SANGAT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 56 69 168.80 5 25005 PREETPAL SINGH GREWAL HARWANT SINGH GREWAL 72 ESM,Punjab 41 58 26 117.60 6 25006 NARENDER SINGH DAULATS INGH 86 BC ESM,Punjab 53 72 154.40 7 25007 RISHI KUMAR MANPHOOL RAM 71 General 65 60 212.00 8 25008 HARDEEP SINGH GURDAS SINGH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 52 73 149.60 9 25009 GURCHARAN KAUR MADAN LAL 85 BC,Punjab 36 88 1 73.60 10 25010 NEELAMUSONDHI SAT PAL SONDHI 71 General 29 96 39.20 11 25011 DALVIR SINGH KARNAIL SINGH 71 General 44 24 57 156.80 12 25012 KARMESH BHARDWAJ S L BHARDWAJ 71 General 99 24 2 376.80 13 25013 ANIL KUMAR GILL DURGA DASS 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 61 33 31 217.60 14 25014 MANINDER SINGH TARA SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab 31 19 75 108.80 15 25015 DEVINDER KUMAR MOHINDER RAM BHUMBLA 72 ESM,Punjab 25 10 90 92.00 16 25016 VIKAS GIRDHAR KHARAITI LAL GIRDHAR 72 ESM,Punjab 34 9 82 128.80 17 25017 RAJIV KUMAR GOYAL BHIM RAJ GOYAL 71 General 45 79 1 116.80 18 25018 NACHHATTAR SINGH GURMAIL SINGH 77 SC Others,Punjab 80 45 284.00 19 25019 HARJEET KUMAR RAM PARKASH 81 Balmiki/Mazhbi Sikh,Punjab 55 70 164.00 20 25020 MANDEEP KAUR AJMER SINGH 76 Physically Handicapped,Punjab 47 59 19 140.80 21 25021 GURDIP SINGH JAGJIT SINGH 72 ESM,Punjab --- --- --- ABSENT 22 25022 HARPREET KANWAR KANWAR JAGBIR SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 83 24 18 312.80 23 25023 GOPAL KRISHAN DAULAT RAM 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT 24 25024 JAGSEER SINGH MODAN SINGH 85 BC,Punjab 33 58 34 85.60 25 25025 SURENDER SINGH TAXAK ROSHAN LAL TAXAK 71 General --- --- --- ABSENT PAGE NO. -

Newsletter Vol 55

NEWSLETTER PAGE NO. 26-29 MAY-JUNE 2021 | VOL. 55 Indian Men's & Women's Hockey Team announcement for the Olympics #IndiaKaGame Newsletter Vol. 55 (May & June 2021) Major Team Partner Follow Us : www.hockeyindia.org @TheHockeyIndia @hockeyindia facebook.com/TheHockeyIndia www.youtube.com/HockeyIndiaMedia www.hockeyindia.org 04 Message from Hockey India President 05-19 20-21 22-25 Top Feature Story Feature Story Highlights Birendra Lakra Hockey India Coaching Education Pathway benefits over 1000 candidates in India 26-29 30-31 32-33 Cover Story Feature Story Feature Story Indian Men's and Women's Indian Men's Hockey Indian Women's Hockey Hockey Team Team Captain dedicating Team Captain dedicating announcement for the Olympic Medal to Olympic Medal to Olympics Covid Warriors Covid Warriors 34-35 36-37 39-45 Feature Story Feature Story Hockey India Savita Hockey India registered Member Unit Umpires Raghuprasad Activites RV and Javed Shaikh on Olympic preparations 46-49 50 51 Media Team In Focus Coverage Birthdays Gurjit Kaur Newsletter Vol. 55 (May & June 2021) Message from Hockey India President Mr. Gyanendro Ningombam Namaskar, The months of May and June were fantasc here at Hockey India. It was absolutely magnificent for Hockey India to be recognized with the Eenne Glichitch Award by the Internaonal Hockey Federaon (FIH) during the virtual conference organised as part of the 47th FIH Congress in May. We are also delighted to note that the Chairman, Managing Director and CEO of Hero MotoCorp, Dr. Pawan Munjal and the Private Secretary to the Hon’ble Chief Minister of Odisha, Shri. -

Page2.Qxd (Page 2)

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 13, 2018 (PAGE 2) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU OBITUARIES UTHALA ANTIM ARDAS With profound grief and sorrow, we inform the sad demise of our beloved Smt Veer Kanta W/o Late Sh Paras Ram Gupta, R/o 86-A (pvt) Gandhi Nagar, Jammu. KIRTAN AND ANTIM ARDAS for the peace of noble soul of CREMATION UTHALA will be performed on (Saturday) 13th Oct 2018 from 4 Pm to 5 Pm at Fateh Sardarni Baljit Kour Wd/O Sardar S w aran Sing h, Re td. Chief With profound grief and sorrow we regret to Singh Gurudwara, Hospital Road Gandhi Nagar main Stop, Jammu. Engineer PDD and Re td. Member PSC., shall be he ld in Guru dw ara inform the sad demise of our beloved father GRIEF STRICKEN : Karamyogi Rattan Lal Tickoo S/o Late Zind Lal Sons & Daughter-in-law Baba Fat eh Sing h Ji, Gandhinagar - Jammu on Saturday 13, Oct ober Lt Sh Rajneesh Gupta & Smt Shashi Bala Tickoo originally R/o Chinkral Mohalla Srinagar 2018 from 11 am t o 12:30 pm. Lt Sh Rakesh Gupta & Smt Dolly Gupta at present Durga Nagar Sect -2 Tallab Tilloo Sh Rajesh Gupta & Smt Pankaj Gupta ANTIM ARDAS will be follow ed b y Guru k a Lang ar (near Darshan Tall) on 12-10-2018 at 2.30 PM. Daughters & Sons-in-law GRIEF STRICKEN: Cremation will take place at Shakti Nagar Ghat Smt Vijay Suri & Sh Krishan Lal Suri at 11 AM on 13/10/108 (Saturday) Smt. Harsh Gupta (Babli) & Sh Pawan Kumar Gupta SONS AND DAUGHTERS-IN-LAW: SISTER AND BROTHER-IN-LAW Brother & Sister-in-law Grief Stricken: Dr. -

Supplementary Electoral Rolls

Punjab Medical Council Electrol Rolls upto 31-01-2018 15363. Dr. Swaran Singh Khehra M.B.B.S. 1960 23-B Vasant Vihar Jalandhar 15.07.1961 5933 20.03.2018 S/o Sh. Gurdhara Singh Khehra 15364. Dr. Gian Praksh Chnader L.S.M.F. 1964 H.No. 1, St. No. 1, Adarsh Nagar, 05.11.1964 7324 25.02.2019 S/o Sh. Amar Chand Sur M.B.B.S. 1967 Dera Bassi Distt. Mohali M.S. (Surgey)1974 15365. Dr. Bharal Lal Jain M.B.B.S. 1964 E-37 Tagore Nagar, Ludhiana 13.11.1964 7335 30.05.2021 S/o Sh. Dogar Mal Jain M.D. (Radiology)1973 15366. Dr. Ravinder Singh S/o M.B.B.S. 1967 38, Gujral Nagar, Jalandhar 29.12.1967 9084 11.11.2018 Sh. Hari Singh Bindra 15367. Dr. Chander Lekha D/o M.B.B.S. 1967 C/o Dr. K. Lal MD Railway Road, 03.01.1968 9106 29.12.2018 Sh. Charan Dass Sood Budhlada 15368. Dr. Amar Satinder Singh M.B.B.S. 1968 Kaulgarh House Officers Enclave 28.04.1969 10154 05.11.2018 S/o Sh. Siasat Singh M.D.(S.P.M.)1977 Patiala 15369. Dr. Narender Kumar S/o M.B.B.S. 1968 79-1, Sarabha Nagar, Ludhiana 04.06.1969 10261 16.02.2021 Sh. Lachhmi Chand 15370. Dr. Vijay Kumar Sharma M.B.B.S. 1969 Gayatri Hospital Sirhind Road, Near 27.01.1970 10686 30.03.2021 S/o Sh. Ishwer Chander Master of Surgery Bypass, Patiala Sharma 1975 15371. -

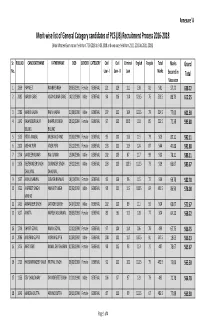

Merit-Wise List of General Category Candidates of PCS (JB)

Annexure 'A' Merit-wise list of General Category candidates of PCS (JB) Recruitment Process 2016-2018 (Main Written Examination held from 7.09.2018 to 9.09.2018 and viva voce held from 21.11.2018 to 28.11.2018) Sr. ROLLNO CANDIDATENAME FATHERNAME DOB GENDER CATEGORY Civil Civil Criminal English Punjabi Total Marks Grand No. Law - I Law - II Law Marks Secured in Total Viva voce 1 1839 PAPNEET RANBIR SINGH 09/05/1991 Female GENERAL 121 129 111 138 82 581 57.22 638.22 2 2082 KARUN GARG VIJAY KUMAR GARG 14/12/1989 Male GENERAL 94 116 114 123.5 76 523.5 88.75 612.25 3 1783 MANIK KAURA RAJIV KAURA 31/08/1990 Male GENERAL 107 112 104 122.5 79 524.5 77.00 601.50 4 1142 RAJANDEEP KAUR BHARPUR SINGH 28/12/1984 Female GENERAL 97 135 88.5 118 85 523.5 72.38 595.88 BILLING BILLING 5 1515 RITIKA KANSAL KRISHAN CHAND 22/02/1990 Female GENERAL 95 100 116 115 79 505 87.11 592.11 6 2100 MEHAK PURI VIVEK PURI 25/12/1991 Female GENERAL 103 111 119 124 87 544 47.88 591.88 7 1734 SANDEEP KUMAR RAJ KUMAR 13/04/1986 Male GENERAL 102 105 87 117 99 510 78.11 588.11 8 1306 REETBRINDER SINGH GURJINDER SINGH 19/12/1991 Male GENERAL 103 115 115.5 112.5 73 519 66.67 585.67 DHALIWAL DHALIWAL 9 1957 ANJALI NARWAL SUBASH NARWAL 14/10/1991 Female GENERAL 95 136 96 115 72 514 68.78 582.78 10 1023 JASPREET SINGH AMARJIT SINGH 02/02/1992 Male GENERAL 98 101 115 108.5 69 491.5 86.50 578.00 MINHAS 11 1455 AMANDEEP SINGH JATINDER SINGH 24/07/1992 Male GENERAL 102 110 89 111 92 504 68.67 572.67 12 1627 ANKITA NARESH AGGARWAL 09/03/1993 Female GENERAL 89 98 112 128 77 504 64.22 -

List of Olympics Prize Winners in Hockey in India

Location Year Players Medals Allan SCHOFIELD Baskaran VASUDEVAN Charanjit KUMAR Chettri CHETTRI Dung Dung SYLVANUS Gurmail SINGH Maharaj Krishon KAUSHIK Mervyn FERNANDIS Moscow 1980 Gold Rajinder SINGH Ravinder PAL SINGH Shahid MOHAMMAD Singh AMARJIT RANA Singh DEAVINDER Singh SURINDER Somaya MANEYPANDA Zafar IQBAL Ajitpal SINGH Ashok KUMAR Billimoga Puttaswamy GOVINDA Cornelius CHARLES Ganesh MOLLERAPOOVAYYA Harbinder SINGH Harcharan SINGH Munich 1972 Bronze Harmik SINGH Krishnamurthy PERUMAL Kulwant SINGH Manuel FREDERICK Michael KINDO Mukhbain SINGH Virinder SINGH Ajitpal SINGH Balbir SINGH Balbir SINGH Balbir SINGH Gurbux SINGH Harbinder SINGH Harmik SINGH Mexico 1968 Inamur REHAMAN Bronze Inder SINGH John PETER Krishnamurthy PERUMAL Munir SAIT Prithipal SINGH Rajendra Absolem CHRISTY Tarsem SINGH www.downloadexcelfiles.com Ali SAYED Bandu PATIL Charanjit SINGH Darshan SINGH Dharam SINGH Gurbux SINGH Harbinder SINGH Tokyo 1964 Haripal KAUSHIK Gold Jagjit SINGH Joginder SINGH John PETER Mohinder LAL Prithipal SINGH Shankar LAXMAN Udham SINGH Charanjit SINGH Govind SAWANT Jaman LAL SHARMA Jaswant SINGH Joginder SINGH John PETER Rome 1960 Joseph ANTIC Silver Leslie CLAUDIUS Mohinder LAL Prithipal SINGH Raghbir SINGH BHOLA Shankar LAXMAN Udham SINGH Amir KUMAR Amit SINGH BAKSHI Bakshish SINGH Balbir SINGH DOSANJH Balkishan SINGH GREWAL Charles STEPHEN Govind PERUMAL Gurdev SINGH Melbourne / Stockholm 1956 Hardyal SINGH Gold Haripal KAUSHIK Leslie CLAUDIUS Raghbir LAL Raghbir SINGH BHOLA Randhir SINGH GENTLE Ranganandhan FRANCIS Shankar -

AGAINST COVID19 As Per Guidelines of Ministry of AYUSH Government of India Dr

AGAINST COVID19 As per guidelines of Ministry of AYUSH Government of India Dr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD (Homoeopathy) Homoeo Cure & Research Institute Phone: NH-74, Dr. Rajneesh Marg, Moradabad +919897618594 Road, Kashipur (Uttarakhand) 244713 Email: INDIA [email protected] 1 1 Contents Courtesy 2 Introduction 3 Role of Homoeopathy in COVID19 pandemic 4 General preventive measures 4 Homoeoprophylaxis against COVID19 5 List of persons who have been prescribed or received the Ars alb 30CH as Homoeoprophylaxis against COVID19 6 www.cureme.org.in 2 Courtesy We are cordially thankful to respected Director Homoeopathy, Uttarakhand, Dr. Rajendra Singh, for his motivation, precious guidance and continuous support in this Herculian endeavor to support the world during this crucial time due to CORONA pandemic through the holistic system of healing i.e. Homoeopathy, by boosting up the immune system of the humanity with Homoeopathic prophylaxis with Ars alb 30 CH.tu www.cureme.org.in 3 Introduction Homoeo Cure & Research Institute has been founded by Dr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma MD (Homoeopathy) in 1994 and providing health solutions to the suffering humanity with classical Homoeopathy all over the world. More than 25 countries in the world and all the states of India are seeking consultations from Dr. Rajneesh Kumar Sharma and getting very satisfactory results. Dr. Sharma is treating acute emergencies with Homoeopathic remedies in well- equipped ICU and NICU at his Sparsh Multispecialty Hospital, situated at Kashipur. In social field, he is actively participating with help of camps, surveys, publishing articles, presenting research papers in various seminars and various projects. Miracles are very frequent in ICU when Homoeopathic remedies are used along with life supporting systems and modalities like Oxygen supply, IV fluids, CPEP, BIPEP and Ventilators etc. -

List of Associate Members A. K. Sharma A. P. Duggal A. S. Dhiman

A List of Associate Members A A. K. Sharma A. P. Duggal A. S. Dhiman A. S. Kalha A. S. Pabla A. S. Thandi A.P. Pandey Ajai Lamba Ajaiwant S. Cheema Ajay K. Jain Ajay Satia Ajay Singh Kadyan Ajit K. Pawar Ajit S. Gulati Ajit S. Sandhu Ajit S. Ubhi Ajit Singh Ajit Singh Virk Ajmer Singh Akash Jain Alok Nehra Amandeep S. Basur Amandeep S. Gill Amar Bir S. Gill Amarjeet S. Bajwa Amarjeet S. Virk Amarjit S. Gill Amarjit S. Kapur Amarjit S. Sidhu Amarjit Singh Amarjit Singh Amarjit Singh Amarjot Singh Amarmeet Singh Benipal Amarpal Singh Amit Dehra Amit Katyal Amit Marwaha Amit Vij Amitpal S. Bhutani Amrik Singh Jaijee Amrinder S. Kang Amrinder Singh Amrit Pal Singh Amrita Kaur Talwar Anant Vyas Aneet Goel Angad Pal S. Kingra Anil Bhola Anil K. Bansal Anil Nagpal Anil Nath Anil Satia Anita Dhawan w/o Harish Dhawan Anup K. Grover Anup Saraf Arjinder S. Bains Arjun Singh Dullat Arpit Shukla Arun I. Keswani Arun K.Verma Arun Kihore Khanna Arun Sekhri Arvind Jatota Arvinder Bains Arvinder S. Bhatia Arvinder S. Parmar Arvinder Singh Asha Devi w/o Mr. C. K. Aggarwal Ashish Arora Ashish Singh Ashok Gupta Ashok K. Laroia Ashok K. Sikka Ashok Kumar Ashok Singal Ashwani Gupta Ashwani Kansal Ashwani Prabhakar Atul Khanna Atul Khosla Avtar Singh Avtar Singh Matharoo A S Bains A S Bindra A. S. Anand A. S. Bindra A. S. Johar A. S. Kang A. S. Khera A. S. Sachdeva A. Sidhu A.S Bindra Abhishek Duggal Achharpal Singh Adesh Partap S. -

List of Advocates 1.Pdf

LIST OF 2017-2018 Sr.no. ENROLL. NO. NAME OF ADVOCATE CONTACT NO. 1 P/3787/2017 ALISHA GUPTA D/O BHUSHAN GUPTA 98773-28547 2 P/3787/2017 ALISHA GUPTA D/O BHUSHAN GUPTA 98773-28547 3 P/1213/1962 A.C. RAMPAL S/O RAM CHAND 95307-95287 4 P/217/1972 A.C.GUPTA S/O KISHAN GOPAL 2441474 5 P/1045/1982 A.K SHORI S/O AMAR NATH SHORI 98760-67377 6 P/1566/2001 A.K. GIRI 7 P/241/1977 A.K. JINDAL 98147-12425 8 P/31/2002 A.N JUNEJA S/O JAWALA SINGH JUNEJA 94173-87127 9 P/903/1992 A.S RANA S/O S.RANJIT SINGH 98151-56382 10 P/557/1978 A.S. ARORA S/O JOGINDER SINGH 94170-56188 11 P/3162/2017 AABROO GUPTA D/O ASHOK K. GUPTA 98153-01457 12 P/4027/2010 AANSHU NAGGAR 13 P/4027/2010 AANSHU NAGGAR 14 P/4027/2010 AANSHU NAGGAR 15 P/4440/2017 AARKIZA WADHERA D/O PRADEEP WADHERA 78377-16004 16 P/750/1990 ABDUL MUJEED THIND S/O NOOR MOHD. 17 P/1555/2006 ABDUL RASHEED S/O MOHAMMED SALEEM 98556-53435 18 P/680/2008 ABDUL RASHID S/O SURAJ DIN 19 P/2407/2012 ABHAY CHOPRA S/O RAKESH CHOPRA 20 P/1744/2016 ABHAY K. JINDAL S/O AJAY K. JINDAL 98149-12425 21 P/2630/2009 ABHAY RAM SHARMA S/O VINOD SHARMA 98030-00724 22 P/2630/2009 ABHAY RAM SHARMA S/O VINOD SHARMA 98030-00724 23 P/3548/2017 ABHEY JOSHI S/O SHIV KUMAR JOSHI 97800-60006 24 P/5711/2017 ABHIJIT SINGH 25 P/3073/2014 ABHIJIT SINGH SANDHU S/O L.S. -

WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE FORCE Current Licence Holders List of Crowd Controllers for September 2021

WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE FORCE Current Licence Holders List of Crowd Controllers for September 2021 Licence NumberFull Name Licence Type 56595 AADITYA, Vijay Crowd Controller 50762 AAKASH, Crowd Controller 58994 AAKESSON, Maximiliam Tobias Crowd Controller 47823 AALAMI, Hamid Reza Crowd Controller 34949 AAMIR, Muhammad Crowd Controller 43372 AAMIR, Sohaib Crowd Controller 58755 AAMIR, Usama Crowd Controller 53982 AATIR, Muhammad Musawar Ali Crowd Controller 46462 AB YAR, Ahmad Crowd Controller 58819 ABADIR, Michael Onsy Adeeb Crowd Controller 27892 ABANDELWA, Lusambya Crowd Controller 72634 ABARCA, Rend Romer Tiamsim Crowd Controller 51532 ABASNEZHAD GHAZE JAHANE, Meysam Crowd Controller 51523 ABASNEZHAD GHAZE JAHANE, Milad Crowd Controller 71160 ABBAS, Abu Bakar Crowd Controller 55088 ABBAS, Ali Crowd Controller 70683 ABBAS, Ali Crowd Controller 44566 ABBAS, Anjum Hussain Crowd Controller 59507 ABBAS, Arslan Crowd Controller 59937 ABBAS, Asad Crowd Controller 34885 ABBAS, Baseer Crowd Controller 72809 ABBAS, Fakhar Crowd Controller 31065 ABBAS, Farukh Crowd Controller 46155 ABBAS, Ghulam Crowd Controller 73154 ABBAS, Haider Crowd Controller 39830 ABBAS, Irfan Crowd Controller 53620 ABBAS, Mazhar Crowd Controller 62014 ABBAS, Mazhar Crowd Controller 33606 ABBAS, Mohsin Crowd Controller 60032 ABBAS, Mohsin Crowd Controller 40778 ABBAS, Mohsin Crowd Controller 70784 ABBAS, Muhammad Crowd Controller 58805 ABBAS, Muhammad Khurram Crowd Controller 71032 ABBAS, Muhammad Soban Crowd Controller 72957 ABBAS, Nadeem Crowd Controller 70396 ABBAS, -

D:\Diary 2020\Dairy New 2020 N

1 Name & Designation Phone Residence Off. Resi. Address gzikp oki GtB PUNJAB RAJ BHAWAN thagha f;zx pdB"o, okigkb 2740740 2740608 Punjab Raj V.P. Singh Badnore, Governor 2746116 2740681 Bhawan/6 wdB gkb, ;eZso$okigkb 2740608 2685090 244/55 Madan Pal, Secy. to Governor 99146-00844 Chd. i/a n?wa pkbkw[o[rB, gqw[Zy ;eZso$okigkb 2740592 2746033 58/5 J. M. Balamurugan, Prin.Secy.to Governor 97800-20243 Chd. r[bôB e[wko, fBZih ;eZso$;eZso$okigkb 2740608 98780-45680 478-A, Gulshan Kumar, Pvt. Secy./Secy. to Governor Harmilap Nagar, Baltana e/apha f;zx, vhankJhaiha J/avha;ha (gh) okigkb 2740609 2971802 31/7-A K.B. Singh, DIG, ADC(P) Governor 98725-21114 w/io g[ôg/Adok f;zx, J/avha;ha (n?w)$okigkb 2740696 94604-30543 52/7-A Maj. Pushpendra Singh, ADC(M)/Governor fôyk Bfjok (ôqhwsh), nkJhaghHnkoHUa 2746095 2773319 2237/ whvhnk okigkb 97800-36106 15-C,Chd. Shikha Nehra (Mrs.), IPRO (Media) to Governor vkH nwohe f;zx uhwk, n?wHTH$ 2792597 2632955 3379/ nkoHphH fv;g?A;oh 97799-13379 46-C Dr. Amrik Singh Cheema, MO, R.B. Disp. Chd. i;d/t f;zx f;ZX{, n?;a gha ;[oZfynk 2740482 98763-71155 1122/69 Jasdev Singh Sidhu, SP Security EPABX-2743224, 2740602, 2740608-10, 2740681, Fax : 2741058 g³ikp ftXkB ;Gk PUNJAB VIDHAN SABHA okDk e/a gha f;zx, ;gheo 2740372 2742976 10/2 Rana K.P. Singh, Speaker 2740739 2740842 F-2740473 okw b'e yskBk, ;eZso$;gheo 2740372 80542-00024 1605/ Ram Lok Khatana, Secretary to Speaker 2740739 94784-44433 38-B okfizdo gq;kd, ftô/ô ekoi nc;o$;gheo 2740372 98722-23329 290/7 Rajinder Prasad, OSD to Speaker ;[fozdo f;zx w'sh, fBZih ;eZso$;gheo 2740739 80543-00021 999/3B-2 Surinder Singh Moti, Pvt. -

Ward No Part No Serial H No Name F Name Sex Age W Name

WARD NO PART NO SERIAL H NO NAME F NAME SEX AGE W NAME ADDRESS 4 1 58 234 PARMINDER SINGH HARBHAJAN SINGH M 39 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 59 234 MANJEET KAUR HARBHAJAN SINGH F 61 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 60 234 HARBHAJAN SINGH SWARN SINGH M 62 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 61 234 BALJINDER SINGH HARBHAJAN SINGH M 38 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 108 149 JAGJEET SINGH ASHA SINGH M 45 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 109 149 MOHINDER KAUR TEJA SINGH F 62 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 110 149 MANJEET KAUR ASHA SINGH F 59 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 112 149 BALWAN SINGH TEJA SINGH M 82 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 113 149 MAHINDER KAUR JAGJIT SINGH F 42 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 129 209 AMARJEET SINGH NIRMAL SINGH M 56 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 132 209 SARAVJEET SINGH NIRMAL SINGH M 50 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 133 209 CHANPRIT SINGH AMRIT SINGH M 29 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 187 33B AMANPREET SINGH KULWANT SINGH M 39 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 244 65 SURINDER SINGH BEDI C S BEDI M 44 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 245 65 MOHINDER BEDI C S BEDI F 71 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 268 88A PARVINDER PAL SINGH AVTAR SINGH M 55 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 269 88A JOGINDER KAUR AVTAR SINGH F 72 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 270 88A KAWALJIT KAUR JAGMOHAN SINGH F 46 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 271 88A DAVINDER KAUR PARVINDER PAL SINGH F 52 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 395 33C SUPREET KAUR BALJIT SINGH F 41 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 484 47 HARVINDER SINGH JOGINDER SINGH M 39 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 559 63 MANJIT SINGH SWARN SINGH M 45 PITAMPURA PITAM PURA 4 1 677 563C KULDEEP KAUR DALJEET SINGH F 48 PITAMPURA