Rainbow Milk Is His First Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Right to Peace, Which Occurred on 19 December 2016 by a Majority of Its Member States

In July 2016, the Human Rights Council (HRC) of the United Nations in Geneva recommended to the General Assembly (UNGA) to adopt a Declaration on the Right to Peace, which occurred on 19 December 2016 by a majority of its Member States. The Declaration on the Right to Peace invites all stakeholders to C. Guillermet D. Fernández M. Bosé guide themselves in their activities by recognizing the great importance of practicing tolerance, dialogue, cooperation and solidarity among all peoples and nations of the world as a means to promote peace. To reach this end, the Declaration states that present generations should ensure that both they and future generations learn to live together in peace with the highest aspiration of sparing future generations the scourge of war. Mr. Federico Mayor This book proposes the right to enjoy peace, human rights and development as a means to reinforce the linkage between the three main pillars of the United Nations. Since the right to life is massively violated in a context of war and armed conflict, the international community elaborated this fundamental right in the 2016 Declaration on the Right to Peace in connection to these latter notions in order to improve the conditions of life of humankind. Ambassador Christian Guillermet Fernandez - Dr. David The Right to Peace: Fernandez Puyana Past, Present and Future The Right to Peace: Past, Present and Future, demonstrates the advances in the debate of this topic, the challenges to delving deeper into some of its aspects, but also the great hopes of strengthening the path towards achieving Peace. -

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

Pittsburgh Overall Score Reports

Pittsburgh Overall Score Reports Mini (8 yrs. & Under) Solo Performance 1 53 Candyman - Center Stage Dance - Burgettstown, PA 82.0 Alaina Swihart 1 555 Dance like your daddy - Spotlight Dance Academy - Deerfield, OH 82.0 Rylie Anthoney 2 484 Little Red - Albright Dance Stars - Monroeville, PA 81.5 Ariya Pisarski 3 137 Wonder Woman - Houck Dance Studio - Uniontown, PA 81.3 Selina Frankhouser 3 347 Charlotte Web - Dance Force Elite - Steubenville, OH 81.3 Charlie Crosier 3 748 Material Girl - Starstruck Dance & Tumbling - North Royalton, OH 81.3 Lexi Day 4 24 Boogie Shoes - Sandra Lynn's School of Dance - Vandergrift, PA 81.0 Alyvia Davis 4 345 Stupid Cupid - Dance Force Elite - Steubenville, OH 81.0 Lexa Davis 4 346 A Dream is a Wish - Dance Force Elite - Steubenville, OH 81.0 Avrie Deah 4 349 Boy from New York city - Dance Force Elite - Steubenville, OH 81.0 Annie Angle 4 551 Bombshell - Spotlight Dance Academy - Deerfield, OH 81.0 Malawna Miller 5 172 I Wanna be a Rockette - The Zone Dance Academy - Schellsburg, PA 80.8 Julianna Fockler 5 348 Baby I'm a Star - Dance Force Elite - Steubenville, OH 80.8 Alexa Hayden 5 690 East Side - Starstruck Dance & Tumbling - North Royalton, OH 80.8 Briella Bingham 6 538 Calling All the Monsters - Sandra Lynn's School of Dance - Vandergrift, PA 80.7 Wynter Maritzer 7 72 These Boots Are Made For Walking - Center Stage Dance - Burgettstown, PA 80.6 Abigail Walker 7 661 Fireball - Studio 412 - Bethel Park, PA 80.6 Aleah Blair 8 456 Heaven is a Place on Earth - Stage West Performing Arts Center - Beaver, -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

A Book of Jewish Thoughts Selected and Arranged by the Chief Rabbi (Dr

GIFT OF Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bookofjewishthouOOhertrich A BOOK OF JEWISH THOUGHTS \f A BOOK OF JEWISH THOUGHTS SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY THE CHIEF EABBI (DR. J. H. HERTZ) n Second Impression HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW COPENHAGEN NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPE TOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI PEKING 5681—1921 TO THE SACRED MEMORY OF THE SONS OF ISRAEL WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918 44S736 PREFATORY NOTE THIS Book of Jewish Thoughts brings the message of Judaism together with memories of Jewish martyrdom and spiritual achievement throughout the ages. Its first part, ^I am an Hebrew \ covers the more important aspects of the life and consciousness of the Jew. The second, ^ The People of the Book \ deals with IsraeFs religious contribution to mankind, and touches upon some epochal events in IsraeFs story. In the third, ' The Testimony of the Nations \ will be found some striking tributes to Jews and Judaism from non-Jewish sources. The fourth pai-t, ^ The Voice of Prayer ', surveys the Sacred Occasions of the Jewish Year, and takes note of their echoes in the Liturgy. The fifth and concluding part, ^The Voice of Wisdom \ is, in the main, a collection of the deep sayings of the Jewish sages on the ultimate problems of Life and the Hereafter. The nucleus from which this Jewish anthology gradually developed was produced three years ago for the use of Jewish sailors and soldiers. To many of them, I have been assured, it came as a re-discovery of the imperishable wealth of Israel's heritage ; while viii PREFATORY NOTE to the non-Jew into whose hands it fell it was a striking revelation of Jewish ideals and teachings. -

DES MOINES REGIONAL February 26-28, 2021 Iowa Events Center

DESMOINESREGIONAL February26Ǧ28,2021 IowaEventsCenter TalentOnParadeisownedandmanagedbyKimberlyandEricMcCluer YourhardworkingTOPstaffforthisshowalsoincludes CalebCeretti,MartiClary,JoeyDoucette,AudraKey,DebraMasur, ScottMcCluer,JohnEarlRobinsonandAmandaWheeler TalentOnParade,LLC AlivePhotoandVideo,LLC (316)522Ͳ4836 (314)472Ͳ5027 talentonparade.com alivephotovideo.com WELCOMETOTOP2021 Weareveryexcitedtowelcomeyoutothis2021regionalcompetition.Thisisour24thseasonand,despitethe extremechallengesofrecentevents,wearethrilledtobebackwithyou.Thefollowingarethe“TOP10” pointstokeepinmindforafun,fairandsafeeventforeveryone. 1. Dancecompetitionbyitsverynatureisasubjectiveevent,meaningitissubjecttoawidevarietyofopinions. Theoutcomeisalsosubjecttoavarietyofchangingcircumstancesthroughoutanygivendaythatyoulikelyhavenocontrol over.It’sjustadancecompetition.Pleaseacceptitforwhatitis.Especiallythisseason.Breathe,relax,havefunandenjoy thischancetodanceregardlessoftheoutcome.Thepastyearhascertainlytaughtusthatyouneverknowwhenyouwillbe allowedtotakethestageagaininthefuture. 2. Videorecordingandphotography(flashornoflash)willbestrictlyprohibitedbyaudiencemembers,except duringawardspresentations.Thisisaverycommonpracticeintheentertainmentindustry,andwithgoodreason. Studiodirectors,teachersandotherparentstendtogetverygrouchywhenchoreographyand/orcostumingarecopied withoutapproval.Moreimportantly,we’retryingtoprotecttheprivacyandsafetyofthekids.Thefactistherearepeople outthereofaveryquestionablenaturewhomaytrytousephotographicimagesinappropriately(gross!). -

Trip Hazzard 1.7 Contents

Trip Hazzard 1.7 Contents Contents............................................ 1 I Got You (I Feel Good) ................... 18 Dakota .............................................. 2 Venus .............................................. 19 Human .............................................. 3 Ooh La La ....................................... 20 Inside Out .......................................... 4 Boot Scootin Boogie ........................ 21 Have A Nice Day ............................... 5 Redneck Woman ............................. 22 One Way or Another .......................... 6 Trashy Women ................................ 23 Sunday Girl ....................................... 7 Sweet Dreams (are made of this) .... 24 Shakin All Over ................................. 8 Strict Machine.................................. 25 Tainted Love ..................................... 9 Hanging on the Telephone .............. 26 Under the Moon of Love ...................10 Denis ............................................... 27 Mr Rock N Roll .................................11 Stupid Girl ....................................... 28 If You Were A Sailboat .....................12 Molly's Chambers ............................ 29 Thinking Out Loud ............................13 Sharp Dressed Man ......................... 30 Run ..................................................14 Fire .................................................. 31 Play that funky music white boy ........15 Mustang Sally .................................. 32 Maneater -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

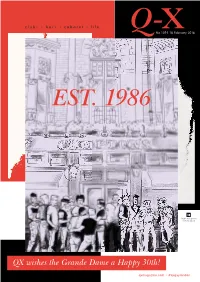

Comptons of Soho

Q-X clubs t bars t cabaret t life No 1093 18 February 2016 EST. 1986 18 Suitable only for persons of 18 years and over QX wishes the Grande Dame a Happy 30th! RYNBHB[JOFDPNtRYHBZMPOEPO QX_1093_Cover.indd 1 16/02/2016 18:43 Comptons of Soho 30 YEARS AT THE HEART OF GAY SOHO As we celebrate the Grand Dame of Soho’s 30th birthday as an offical gay venue, we have a chat with some of her nearest and dearest. They know her best and they, in addition to their hundreds of regulars, make her what she is. Happy Birthday old girl! Neil Hodgson, Landlord Comptons as a gay bar was evolving long before the 1980’s and there are reports of metropolitan police warnings about sodomy on the premises as early as the 1940’s. It was 1986 that bar was officially declared as gay. I’ve been fortunate enough to have been General Manager here for 17 of those 30 years. Together we have witnessed and survived a lot together, bombings, hate crimes, riots, the loss of some very special people and places over the years including an economic recession and the ongoing gentrification of Soho. Despite my keenness to dress up in uniforms I still only very much remain a caretaker of an institution that belongs to the people that support it also who have made it the solid institution it is today and still she continues to grow. Comptons to me is a real place and its people, it’s also my work and my home. -

Meet the Judges

Meet The Judges Liz Ernst Overland Park, Kansas Liz Ernst holds a Bachelors of Fine Arts in Dance, and a Masters of Fine Arts in Dance. Liz has performed professionally as an industrial dancer, commercial dancer in numerous musicals throughout the U.S. There probably isn't a musical she hasn't either been in or choreographed. She spent a couple years in Branson, MO dancing at various theaters & theme parks. Besides performing, Liz has been an Assistant Professor of Dance at K-State, on dance faculty at University of Iowa, Dance Chair for a performing arts high school, and taught at such dance intensives as: Ailey Camps, American College Dance Festival, Midwest Dance Alliance, The Tap Festival to name a few. She has also written dance curriculum for Edison Charter schools. Teaching and choreography are her true passion. Liz has spent the past 25 years fine tuning the art of teaching dance, and still learns something new each week! Joseph Creagh San luis Obispo, California Joseph Conrad Creagh is a proud alumnus of The Dance Spot in Fullerton, California. He began his professional career at a young age as a series regular on The Disney Channel’s Kids Incorporated, and created the role of Jake in Walt Disney Pictures’ Newsies! Having established a twenty-five year career in the entertainment industry, Joseph has performed in 11 countries over three decades encompassing film, television, theater, and stage productions. Joseph has created choreography and staging for the Walt Disney Company, Holland America Cruise Line, Cedar Fair, Mel B, Days of Our Lives, Elvira “Mistress of the Dark”, Ann-Margret, and Andy Williams, as well as numerous award-winning, celebrity magic shows, corporate events, and theme park attractions. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

BALANCED SCORECARD STEP-BY-STEP for GOVERNMENT and NONPROFIT AGENCIES Second Edition

BALANCED SCORECARD STEP-BY-STEP FOR GOVERNMENT AND NONPROFIT AGENCIES Second Edition Paul R. Niven John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 3/4/08 11:06:55 AM ffirs.indd ii 3/4/08 11:06:55 AM BALANCED SCORECARD STEP-BY-STEP FOR GOVERNMENT AND NONPROFIT AGENCIES Second Edition ffirs.indd i 3/4/08 11:06:55 AM ffirs.indd ii 3/4/08 11:06:55 AM BALANCED SCORECARD STEP-BY-STEP FOR GOVERNMENT AND NONPROFIT AGENCIES Second Edition Paul R. Niven John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 3/4/08 11:06:55 AM This book is printed on acid-free paper. ϱ Copyright © 2008 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.