Self-Portrait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Never-Before-Seen Documents Reveal IWM's Plan for Evacuating Its Art

Never-before-seen documents reveal IWM’s plan for evacuating its art collection during the Second World War Never-before-seen documents from Imperial War Museums’ (IWM) collections will be displayed as part of a new exhibition at IWM London, uncovering how cultural treasures in British museums and galleries were evacuated and protected during the Second World War. The documents, which include a typed notice issued to IWM staff in 1939, titled ‘Procedure in the event of war,’ and part of a collection priority list dated 1938, are among 15 documents, paintings, objects, films and sculptures that will be displayed as part of Art in Exile (5 July 2019 – 5 January 2020). At the outbreak of the Second World War, a very small proportion of IWM’s collection was chosen for special evacuation, including just 281works of art and 305 albums of photographs. This accounted for less than 1% of IWM’s entire collection and 7% of IWM’s art collection at the time, which held works by prominent twentieth- century artists including William Orpen, John Singer Sargent, Paul Nash and John Lavery. Exploring which works of art were saved and which were not, Art in Exile will examine the challenges faced by cultural organisations during wartime. With the exodus of Britain’s cultural treasures from London to safety came added pressures on museums to strike a balance between protecting, conserving and displaying their collections. The works on IWM’s 1938 priority list, 60 of which will be reproduced on one wall in the exhibition, were destined for storage in the country homes of IWM’s Trustees, where it was believed German bombers were unlikely to venture. -

Two Artworks by Jock Mcfadyen to Go on Permanent Display at IWM North As Imperial War Museums Marks 30 Years Since the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Two artworks by Jock McFadyen to go on permanent display at IWM North as Imperial War Museums marks 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall To coincide with the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Christmas in Berlin (1991) and Die Mauer (1991), painted by renowned artist Jock McFadyen, will be going on permanent display at IWM North. This is the first time in over a decade that the paintings have been on public display. The fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 signalled the end of the Cold War, triggering the reunification of Germany and the subsequent dissolution of the USSR. Europe was reshaped, both in its physical borders and its political and social identity, which continue to evolve today. In 1990, the year following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Scottish artist Jock McFadyen was commissioned by Imperial War Museums to respond to this momentous event in history and to record its impact on the city and its residents. In Christmas in Berlin (left), McFadyen blurs the distinction between the Wall and the cityscape of Berlin. The Wall can be seen covered in vividly coloured markings and large-scale symbols representing graffiti, set against a wintry grey background. In the distance, festival lights, one in the shape of a Christmas tree, shine dimly against the buildings. Beyond the Wall, the iconic sphere of the Berliner Fernsehturm (Television Tower) in Alexanderplatz dominates the skyline. During the Cold War, residents of East Berlin would visit the top of the Tower, which was the highest point in the city, to view the West. -

Annual Review Are Intended Director on His fi Rst Visit to the Gallery

THE April – March NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY April – March – Contents Introduction 5 In June , Dr Nicholas Penny announced During Nicholas Penny’s directorship, overall Director’s Foreword 8 his intention to retire as Director of the National visitor numbers have grown steadily, year on year; Gallery. The handover to his successor, Dr Gabriele in , they stood at some . million while in Acquisitions 10 Finaldi, will take place in August . The Board they reached over . million. Furthermore, Loans 17 looks forward to welcoming Dr Finaldi back to this remarkable increase has taken place during a Conservation 24 the Gallery, where he worked as a curator from period when our resource Grant in Aid has been Framing 28 to . falling. One of the key objectives of the Gallery Exhibitions 32 This, however, is the moment at which to over the last few years has been to improve the Displays 44 refl ect on the directorship of Nicholas Penny, experience for this growing group of visitors, Education 48 the eminent scholar who has led the Gallery so and to engage them more closely with the Scientifi c Research 52 successfully since February . As Director, Gallery and its collection. This year saw both Research and Publications 55 his fi rst priority has been the security, preservation the introduction of Wi-Fi and the relaxation Public and Private Support of the Gallery 60 and enhanced display of the Gallery’s pre-eminent of restrictions on photography, changes which Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 66 collection of Old Master paintings for the benefi t of have been widely welcomed by our visitors. -

Aldwych-House-Brochure.Pdf

Executive summary • An iconic flagship in the heart of Midtown • This imposing building invested with period grandeur, has been brought to life in an exciting and modern manner • A powerful and dramatic entrance hall with 9 storey atrium creates a backdrop to this efficient and modern office • A total of 142,696 sq ft of new lettings have taken place leaving just 31,164 sq ft available • A space to dwell… 4,209 – 31,164 SQ FT 4 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 5 Aldwych House • MoreySmith designed reception • Full height (9 storey) central atrium fusing a modern which provides a light, modern, interior with imposing spacious circulation area 1920s architecture • Floors are served by a newly refurbished lightwell on the west side and a dramatically lit internal Aldwych House totals 174,000 atrium to the east from lower sq ft over lower ground to 8th ground to 3rd floor floors with a 65m frontage • An extensive timber roof terrace onto historic Aldwych around a glazed roof area • Showers, cycle storage and a drying room are located in the basement with easy access from the rear of the building • The ROKA restaurant is on the ground floor 6 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 7 8 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM Floorplate Typical upper floor c. 18,000 sq ft Typical upper floor CGI with sample fit-out 10 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 11 Floorplate Typical upper floor with suite fit-out 12 | ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM ALDWYCHHOUSE.COM | 13 SOHO TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD MIDTOWN | LONDON Aldwych House, now transformed as part of the dynamic re-generation of this vibrant eclectic midtown destination, stands tall and COVENT GARDEN commanding on the north of the double crescent of Aldwych. -

National Gallery Exhibitions, 2010

EXHIBITIONS AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY 2010 PRESS NOTICE MAJOR EXHIBITION PAINTING HISTORY: DELAROCHE AND LADY JANE GREY 24 February – 23 May 2010 Sainsbury Wing Admission charge Paul Delaroche was one of the most famous French painters of the early 19th century, with his work receiving wide international acclaim during his lifetime. Today Delaroche is little known in the UK – the aim of this exhibition is to return attention to a major painter who fell from favour soon after his death. Delaroche specialised in large historical tableaux, frequently of scenes from English history, characterised by close attention to fine detail and often of a tragic nature. Themes of imprisonment, execution and martyrdom Paul Delaroche, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey, 1833 © The National Gallery, London were of special interest to the French after the Revolution. The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (National Gallery, London), Delaroche’s depiction of the 1554 death of the 17-year-old who had been Queen of England for just nine days, created a sensation when first exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1834. Monumental in scale, poignant in subject matter and uncanny in its intense realism, it drew amazed crowds, as it still does today in London. This exhibition will, for the first time in the UK, trace Delaroche’s career and allow this iconic painting to be seen in the context of the works which made his reputation, such as Marie Antoinette before the Tribunal (1851, The Forbes Collection, New York). Together with preparatory and comparative prints and drawings for Lady Jane Grey on loan from collections across Europe, it will explore the artist’s notion of theatricality and his ability to capture the psychological moment of greatest intensity which culminated in Lady Jane Grey. -

Student Handout

Open Arts Objects Open Arts Archive http://www.openartsarchive.org/open-arts-objects Presenter: Veronica Davies Object: Catalogue - War Pictures at the National Gallery (1942) Dr Veronica Davies examines a catalogue produced for an exhibition of war artists' work at the National Gallery in 1942 This video will help you think about art in wartime, how works of art are exhibited, and what a catalogue might tell us about a historical exhibition, the circumstances in which it was produced and the kind of art that was on show. Before watching the film Before you watch the video, think about and discuss the following questions: 1. What do you know about the period of World War Two (1939-45) in Britain? 2. What do you think would be the difficulties faced by artists employed as war artists? 3. What do you think would be the difficulties in putting on an exhibition during war time? After watching the film 1. Questions for discussion and debate The War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC) was part of the wartime Ministry of Information, which, among other things, was tasked with raising public morale and providing propaganda. a. Are these appropriate roles for art? b. Should art ever be censored? 2. Looking closer a. The two works highlighted in the video are both now in the Imperial War Museum, which was given a large proportion of the output of the WAAC when the war was over. Kenneth Rowntree CEMA Concert, Isle of Dogs http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/23463 Michael Ford War weapons week in Country Town http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/9684 Choose one of them, and find out what you can about it from the linked web page. -

Aldwych Key Features

61 ALDWYCH KEY FEATURES 4 PROMINENT POSITION ON CORNER OF ALDWYCH AND KINGSWAY HOLBORN, STRAND AND COVENT GARDEN ARE ALL WITHIN 5 MINUTES’ WALK APPROXIMATELY 7,500 – 45,000 SQ FT OF FULLY REFURBISHED OFFICE ACCOMMODATION AVAILABLE 2,800 SQ FT ROOF TERRACE ON 9TH FLOOR DUAL ENTRANCES TO THE BUILDING OFF ALDWYCH AND KINGSWAY TEMPLE 61 ALDWYCH 14 KINGSWAY 6 HOLBORN COVENT GARDEN FARRINGDON 14 4 CHANCERY LANE N LOCAL AMENITIESSmitheld Market C NEWMAN’S ROW 15 HOLBORN H A 12 N C E OCCUPIERS R 13 FARRINGDON STREET 7 Y 1 British American Tobacco 9 Fladgates TOTTENHAM COURT ROAD L A 2 BUPA 10 PWC KINGSWAY N 3 11 Tate & Lyle D R U R Y L N E LSE 6 4 Mitsubishi 12 ACCA 11 5 Shell 13 Law Society E 9 N 6 Google 14 Reed D 7 Mishcon De Reya 15 WSP E E V L 8 Coutts 16 Covington and Burlington L A S 10 Y T LINCOLN’S INN FIELDS 13 R GREAT QUEEN ST U 3 C A R E Y S T RESTAURANTS B S Covent E 1 Roka 8 The Delauney T Garden F 2 The Savoy 9 Rules A CHARING CROSS RD Market 61 8 H 3 STK 10 Coopers S ALDWYCH 1 4 L’Ate l i e r 11 Fields Bar & Kitchen 11 5 The Ivy 12 Mirror Room and Holborn 16 N D 6 Dining Room 5 8 L D W Y C H A Radio Rooftop Bar 4 2 A R 13 8 L O N G A C R E 3 S T 7 Balthazar Chicken Shop & Hubbard 4 and Bell at The Hoxton COVENT GARDEN 7 LEISURE & CULTURE 6 3 1 National Gallery 6 Royal Festival Hall 1 2 7 Theatre Royal National Theatre ST MARTIN’S LN 3 Aldwych Theatre 8 Royal Courts of Justice LEICESTER 5 4 Royal Opera House 9 Trafalgar Square 5 Somerset House BLACKFRIARS SQUARE 9 2 TEMPLE BLACKFRIARS BRIDGE T 2 E N K M N B A STRAND M E 5 I A R WATERLOO BRIDGE O T STAY CONNECTED 1 C 8 12 I V CHARING CROSS STATION OXO Tower WALKING TIME 9 Holborn 6 mins Temple 8 mins Trafalgar Square Covent Garden 9 mins 10 NORTHUMBERLAND AVE Leicester Square 12 mins EMBANKMENT 7 Charing Cross 12 mins Embankment 12 mins Chancery Lane 13 mins Tottenham Court Road 15 mins 6 London Eye WATERLOO RD THE LOCATION The building benefits from an excellent location on the corner of Aldwych and Kingsway, which links High Holborn to the north and Strand to the south. -

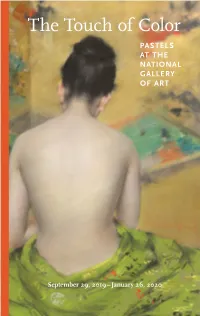

The Touch of Color PASTELS at the NATIONAL GALLERY of ART

The Touch of Color PASTELS AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART September 29, 2019 – January 26, 2020 FIRST USED DURING THE RENAISSANCE, pastels are still manufac- tured from a carefully balanced mix of pigment, a filler such as chalk or clay, and a binder, then shaped into sticks and dried. With a single stroke of this stick, the artist applies both color and line. Because of the medi- um’s soft, crumbly texture, the line can be left intact or smudged with a finger or stump (a rolled piece of leather or paper) into a broad area of tone. Pastelists have used this versatile medium in countless different ways over the centuries. Some have covered the surface of the paper or other support with a thick, velvety layer of pastel, while others have taken a more linear approach. Some have even ground the stick to a powder and rubbed it into the support, applied it with a stump, or moist- ened it and painted it on with a brush. Throughout history, the views of artists and their audiences toward the medium have varied as widely as the techniques of those who used it. 2 Fig. 1 Benedetto Luti, Head of a Fig. 2 Rosalba Carriera, Allegory of Bearded Man, 1715, pastel and colored Painting, 1730s, pastel and red chalk chalks on paper, National Gallery of Art, on blue paper, mounted on canvas, Washington, Julius S. Held Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund Samuel H. Kress Collection A few sixteenth-century Italian artists mimicked the lifelike appearance of flaw- used pastel to block out colors in prepara- less skin. -

National Gallery Strategic Plan 2018–2023

STRATEGIC PLAN 2018–2023 INTRODUCTION The National Gallery exists so that people can engage with great art. From its inception the National Gallery has been free for all to visit. We believe that free admission represents a commitment to the public It is a public museum with a uniquely important collection of pictures for which must be reaffirmed and developed, a commitment to visitors of the benefit of all. It tells a coherent story of European painting spanning all ages, from Britain and abroad, and from all walks of life. seven centuries and reflects how artists and the societies in which they lived have responded to myth and religion, history and contemporary The National Gallery has an important role to play in enabling people events, landscape and the human form, and to the tradition of art itself. to understand and negotiate the changes that society is undergoing The National Gallery constitutes a living legacy of humanity’s highest by providing long-term historical perspective, mediated access to works cultural achievements in painting and is an inestimable resource for of art of great significance and beauty, and a safe environment for understanding the world as we have inherited it. reflection on questions of identity, beliefs, and on the relationship between the past and the present. We who currently have responsibility for the Gallery want to share this resource, and our enthusiasm for it, with the widest possible audience. Taking the changing world our audience lives in as its context, and as we approach the National Gallery’s bicentenary in 2024, this Strategic Plan Established in 1824, the National Gallery is a national responsibility sets out our vision for the future. -

![View Our Entertaining Brochure [PDF 6.6MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9557/view-our-entertaining-brochure-pdf-6-6mb-1619557.webp)

View Our Entertaining Brochure [PDF 6.6MB]

YOUR EVENT AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY Phone: +44 20 7747 5931 · Email: [email protected] · Twitter: @NG_EventsLondon · Instagram: @ngevents We are one of the most visited galleries in the world. Located on Trafalgar Square, we have stunning views of Nelson’s Column, Westminster and beyond. Surround your guests with some of the world’s greatest paintings by artists such as Leonardo, Monet and Van Gogh. Our central location, magnificent architecture and spectacular spaces never fail to impress. 2 The Portico The Mosaic Central Hall Room 30 The Barry Annenberg Gallery A The Yves Saint The Wohl Room The National Café The National Terrace Rooms Court Laurent Room Dining Room East Wing East Wing East Wing East Wing East Wing East Wing North Wing North Wing West Wing East Wing Sainsbury Wing Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12 Page 14 Page 15 3 THE PORTICO With unrivalled views overlooking Trafalgar Square, the Portico Terrace is our most impressive outdoor event space. Breakfast 100 · Reception 100 · Reception including foyer 250 · Dinner 60 Level 2 DID YOU KNOW … The relief above the Portico entrance shows two young women symbolising Europe and Asia. This relief was originally intended for John Nash’s Marble Arch. 4 · East Wing THE MOSAIC TERRACE Step inside the Gallery onto our historic mosaic floor, beautifully lit by a domed glass ceiling. This unique artwork by Boris Anrep combines an ancient technique with contemporary personalities of 1930’s Britain such as Greta Garbo and Virginia Woolf. -

The National Gallery Review of the Year 2007-2008

NG Review 2008 cover.qxd 26/11/08 13:17 Page 1 the national gallerythe national of the year review 2008 april 2007 ‒ march THE NATIONAL GALLERY review of the year april 2007 ‒ march 2008 the national gallery the national NG Review 2008 cover.qxd 28/11/08 17:09 Page 2 © The National Gallery 2008 Photographic credits ISBN 978-1-85709-457-2 All images © The National Gallery, London, unless ISSN 0143 9065 stated below Published by National Gallery Company on behalf of the Trustees Front cover: Paul Gauguin, Bowl of Fruit and The National Gallery Tankard before A Window (detail), probably 1890 Trafalgar Square London WC2N 5DN Back cover: A cyclist stops in a London street to admire a reproduction of Rubens’s Samson and Tel: 020 7747 2885 Delilah, part of The Grand Tour www.nationalgallery.org.uk [email protected] Frontispiece Room 29, The National Gallery © Iain Crockart Printed and bound by Westerham Press Ltd. St Ives plc p. 9 Editors: Karen Morden and Rebecca McKie Diego Velázquez, Prince Baltasar Carlos in the Riding Designed by Tim Harvey School, private collection. Photo © The National Gallery, London p. 18 Sebastiano del Piombo, Portrait of a Lady, private collection © The National Gallery, courtesy of the owner Paul Gauguin, Still Life with Mangoes © Private collection, 2007 p. 19 Richard Parkes Bonington, La Ferté © The National Gallery, London. Accepted in lieu of Tax Edouard Vuillard, The Earthenware Pot © Private collection p. 20 Pietro Orioli, The Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome, Bernardino, Catherine of Alexandria and Francis © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford p. -

Bernardo Bellotto (Venice 1721-1780 Warsaw)

PROPERTY FROM A DISTINGUISHED PRIVATE COLLECTION ■9 BERNARDO BELLOTTO (VENICE 1721-1780 WARSAW) View of Verona with the Ponte delle Navi oil on canvas 52q x 92q in. (133.3 x 234.8 cm.) painted in 1745-47 £12,000,000-18,000,000 US$18,000,000-26,000,000 €14,000,000-21,000,000 PROVENANCE: LITERATURE: Anonymous sale ‘lately consigned from abroad’; Christie’s, 30 March [=2nd M. Chamot, ‘Baroque Paintings’, Country Life, LX, 6 November 1926, p. 708. day] 1771, lot 55, as 'Canaletti', 'its companion [lot 54; A large and most capital A. Oswald, ‘North Mymms Park, II’, Country Life, LXXV, 20 January 1934, picture, being a remarkable view of the city of Verona, on the banks of the pp. 70-1, fig. 13. Adige. This picture is finely coloured, the perspective, its light and shadow S. Kozakiewicz, in Bernardo Bellotto 1720-1780, Paintings and Drawings from fine and uncommonly high finish’d’; 250 guineas to Grey] exhibiting another the National Museum of Warsaw, exhibition catalogue, London, Whitechapel view of the same city, equally fine, clear and transparent’, the measurements Art Gallery, Liverpool, York and Rotterdam (catalogue in Dutch), 1957, p. 25, recorded as 53 by 90 inches (250 guineas to ‘Fleming’, ie. the following). under no. 32. Gilbert Fane Fleming (1724-1776), Marylebone; Christie’s, London, 22 May W. Schumann and S. Kozakiewicz, in Bernardo Bellotto, genannt Canaletto 1777, as ‘Canaletti. A view of the city of Verona, esteemed the chef d’œuvre of in Dresden und Warschau, exhibition catalogue, Dresden, 1963, respectively the master’ (205 guineas to ‘Ld Cadogan’, i.e.