Definition of a False Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine Biomed Central

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access The supernatural characters and powers of sacred trees in the Holy Land Amots Dafni* Address: Institute of Evolution, the University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel Email: Amots Dafni* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 25 February 2007 Received: 29 November 2006 Accepted: 25 February 2007 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2007, 3:10 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-3-10 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/3/1/10 © 2007 Dafni; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract This article surveys the beliefs concerning the supernatural characteristics and powers of sacred trees in Israel; it is based on a field study as well as a survey of the literature and includes 118 interviews with Muslims and Druze. Both the Muslims and Druze in this study attribute supernatural dimensions to sacred trees which are directly related to ancient, deep-rooted pagan traditions. The Muslims attribute similar divine powers to sacred trees as they do to the graves of their saints; the graves and the trees are both considered to be the abode of the soul of a saint which is the source of their miraculous powers. Any violation of a sacred tree would be strictly punished while leaving the opportunity for atonement and forgiveness. The Druze, who believe in the transmigration of souls, have similar traditions concerning sacred trees but with a different religious background. -

Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim‐

JOURNAL for the SCIENTIFIC STUDY of RELIGION Religious Fundamentalism in Eight Muslim-Majority Countries: Reconceptualization and Assessment MANSOOR MOADDEL STUART A. KARABENICK Department of Sociology Combined Program in Education and Psychology University of Maryland University of Michigan To capture the common features of diverse fundamentalist movements, overcome etymological variability, and assess predictors, religious fundamentalism is conceptualized as a set of beliefs about and attitudes toward religion, expressed in a disciplinarian deity, literalism, exclusivity, and intolerance. Evidence from representative samples of over 23,000 adults in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and Turkey supports the conclusion that fundamentalism is stronger in countries where religious liberty is lower, religion less fractionalized, state structure less fragmented, regulation of religion greater, and the national context less globalized. Among individuals within countries, fundamentalism is linked to religiosity, confidence in religious institutions, belief in religious modernity, belief in conspiracies, xenophobia, fatalism, weaker liberal values, trust in family and friends, reliance on less diverse information sources, lower socioeconomic status, and membership in an ethnic majority or dominant religion/sect. We discuss implications of these findings for understanding fundamentalism and the need for further research. Keywords: fundamentalism, Islam, Christianity, Sunni, Shia, Muslim-majority countries. INTRODUCTION -

The Leaves of One Tree: Religious Minorities in Lebanon Rania El Rajji

briefing The leaves of one tree: Religious minorities in Lebanon Rania El Rajji ‘You are all fruits of one tree and the leaves of one names and details have been withheld. MRG would also branch.’ like to thank all those who took part in its roundtable event Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Bahá’i faith for their thoughts and contributions. Introduction Country background In the midst of a region in turmoil, where the very future While Lebanon’s history of Confessionalism – a form of of religious minorities seems to be at stake, Lebanon has consociationalism where political and institutional power is always been known for its rich diversity of faiths. With a distributed among various religious communities – can be population of only 4.5 million people,1 the country hosts traced further back, its current form is based on the more than 1 million refugees and officially recognizes 18 unwritten and somewhat controversial agreement known as different religious communities among its population.2 the National Pact. Developed in 1943 by Lebanon’s Lebanon’s diversity has also posed significant challenges. dominant religious communities (predominantly its The country’s history indicates the potential for religious Christian and Sunni Muslim populations), its stated tensions to escalate, especially in a broader context where objectives were to unite Lebanon’s religious faiths under a sectarian violence has ravaged both Iraq and Syria and single national identity. threatens to create fault lines across the region. The war in It laid the ground for a division of power along religious Syria has specifically had an impact on the country’s lines, even if many claim it was done in an unbalanced stability and raises questions about the future of its manner: the National Pact relied on the 1932 population minorities. -

The Case of Druze Society and Its Integration in Higher Education in Israel

International Education Studies; Vol. 13, No. 8; 2020 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Case of Druze Society and its Integration in Higher Education in Israel Aml Amer1 & Nitza Davidovitch1 1 Department of Education, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel Correspondence: Nitza Davidovitch, Department of Education, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel, Kiriat Hamada 3, Ariel, Israel. E-mail: [email protected] Received: February 23, 2020 Accepted: April 24, 2020 Online Published: July 23, 2020 doi:10.5539/ies.v13n8p68 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v13n8p68 Abstract In this work, we elaborate on the changes and transformations in the Israeli education system (including higher education) from Israel’s independence in 1948 to 2019. Specifically, the study places special emphasis on developments commencing in 1976 in response to the establishment of a separate administrative division for Druze and Circassian Education in the Ministry of Education, and division’s impact on the rate of youngsters who earn matriculation certificates and the number of Druze students attending higher education institutions. of the study analyzes the administrative separation of Druze education in the education system and its effect on the integration of Druze youngsters in higher education in Israel. The current study contributes to our understanding of the development of the Druze education system as a distinct unit in the Israeli Ministry of Education. The findings of this study and its conclusions will contribute to policymakers in the Ministry of Education in general, and policymakers concerning Druze education specifically, seeking to improve educational achievements and apply the insights of the current study to other minority groups to which higher education has become increasingly accessible in recent years. -

Ethnicity and Values Among the Lebanese Public: Findings from Avalues Survey

ETHNICITY AND VALUES AMONG THE LEBANESE PUBLIC: FINDINGS FROM AVALUES SURVEY Mansoor Moaddel In the spring of 2008, Mansoor Moaddel, in collaboration with researchers in Lebanon— Hilal Khashan, Political Science Professor of American University in Beirut, Johan Gärde from Ersta Sköndal University College/Sweden, and Jean Kors of the International Center for Organizational Development, Beirut, Lebanon—launched the first world values survey in Lebanon. The objective of this project was to understand the mass-level belief systems of the Lebanese public. The project was designed to provide a comprehensive measure of all major areas of human concerns from religion to politics, economics, culture, family, and inter-ethnic and international relations. This survey used a nationally representative sample of 3,039 adults from all sections of Lebanese society. The sample included 954 (31%) Shi’is, 753 (25%) Sunnis, 198 (7%) Druze, 599 (20%) Maronites, 338 (11%) Orthodox, 149 (5%) Catholics, and 48 (2%) respondents belonging to other religions. It covered all six governorates in proportion to size— 960 (32%) from Beirut, 578 (19%) from Mount Lebanon, 621 (20%) from the North, 339 (11%) from Biqqa, and 539 (18%) from the South and Nabatieth. The interviews took approximately 50 minutes to complete and were conducted face-to-face by Lebanese personnel in the respondents’ residences. The total number of completed interviews represented 86% of attempted observations. Data collection started in April 2008 and was completed at the end of September 2008. Turbulent political and security situation in Lebanon in the spring and summer prolonged the survey period. The respondents had an average age of 33 years, 1,694 (55.7%) were male, and 998 (32.8%) had a college degree. -

The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905 Manal Kabbani College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kabbani, Manal, "The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626979. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5ysg-8x13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905 Manal Kabbani Springfield, Virginia Bachelors of Arts, College of William & Mary, 2013 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Comparative and Transnational History The College of William and Mary January 2016 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (anal Kabbani . Approved by the Committee, October, 2014 Committee Chair Assistant Professor Ayfer Karakaya-Stump, History The College of William & Mary Associate Professor Hiroshi Kitamura, History The College of William & Mary AssistafvTProfessor Fahad Bishara, History The College of William & Mary ABSTRACT In August of 1905, American newspapers reported that the Greek Orthodox Bishop of the American Antioch, Rafa’el Hawaweeny, asked his Syrian migrant congregation to lay down their lives for him and kill two prominent Maronite newspaper editors in Little Syria, New York. -

LEBANON Executive Summary the Constitution and Other Laws And

LEBANON Executive Summary The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom and, in practice, the government generally respected religious freedom. The constitution declares equality of rights and duties for all citizens without discrimination or preference but establishes a balance of power among the major religious groups. The government did not demonstrate a trend toward either improvement or deterioration in respect for and protection of the right to religious freedom. There were reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. There was tension among religious groups, attributable in part to competition for political power, and citizens continued to struggle along sectarian lines with the legacy of a 15-year civil war (1975-90). Divisions and rivalries among various groups have existed for many centuries and, while relationships among adherents of different confessions were generally amicable, group identity was highly significant in most aspects of cultural interaction. Despite tensions generated by the competition for political power, places of worship of every confession continued to exist side by side, reflecting the country’s centuries-old heritage as a place of refuge for those fleeing religious intolerance. The U.S. government discussed religious freedom and the importance of peaceful coexistence and mutual respect as part of its overall policy to promote human rights and stability in Lebanon. The ambassador and embassy officers met regularly with leaders -

The Future of Christian Mission in Lebanon

The Future of Christian Mission in Lebanon Norman A. Horner n January 1977 I published an article in the Occasional and business, better educational facilities than existed anywhere I Bulletin of Missionary Research' under the title "The else in the region, and relative economic affluence. It was also the Churches and the Crisis in Lebanon." I had just returned from a one country of the area where Christians and Muslims collabo mission of eight years in the Middle East, with primary residence rated more or less harmoniously in the social and political order. in Beirut, and had personally experienced the first eighteen Under the surface, however, there was resentment in other months of the Lebanese civil war. In that article I maintained that Christian communities as well as among the Muslims and Druze this war is basically over social and political issues rather than re against the Maronite hegemony. There was also as much resis ligious issues as such. I believe that my analysis accurately re tance to any change in religious affiliation as existed in the more flected the situation at that time, and I would not now retract any conservative Muslim states of the region. Any increase in the ratio of the statements except for a too-eas y assumption that the coun of Christians to Muslims was seen by the Muslims as a further try was even then on the road to recovery. The war has instead threat to the uneasy population balance and to their already sub dragged on for seven more years, reaching an intensity that no servient position in the body politic. -

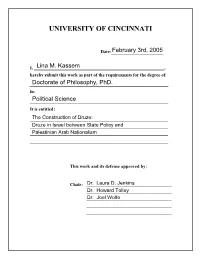

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

Deluty and Rose

THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES IMES CAPSTONE PAPER SERIES THE STATE OF ISRAEL AND THE DRUZE COMMUNITY: IMPLICATIONS FOR MINORITY INCLUSION IN THE MIDDLE EAST ALISHA DELUTY KELLI ROSE MAY 2014 THE INSTITUTE FOR MIDDLE EAST STUDIES THE ELLIOTT SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY © ALISHA DELUTY AND KELLI ROSE, 2014 Acknowledgements Our utmost gratitude goes to Dr. Barak Salmoni for his insightful scholarship, invaluable guidance, and consistent dedication throughout every step of this project. We would like to extend our appreciation to Dr. Marc Lynch and Dr. Shana Marshall of the Institute for Middle East Studies for their support and assistance in this research. This project would not have been possible without the Israeli Druze and Jews who took the time to speak with us and share their personal stories and experiences. We would like to thank the Abu Tareef family for graciously hosting us and answering our many questions. We are indebted to Dr. Shimon Avivi, Dr. Gabriel Ben-Dor, Dr. Salim Brake, and Dr. Rami Zeedan for sharing their indispensable knowledge with us. We are also grateful to Member of Knesset Hamad Amar who gave us his undivided attention and engaged in a stimulating discussion with us in both Hebrew and Arabic. We would also like to thank Abe Lapson and Moran Stern, for their additional insights into this research, and Ahmed Ben Hariz for his assistance in translating our interviews. Shukran and Todah! We would like to give a special thank you to our family and friends, particularly Daniel Rose, Vera Rose, Vivien Rose, Dr.