The Changing Role of Clergy More Called to Congratulate Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institution Name City State

Institution Name City State Abilene Christian University Abilene TX Adams State University Alamosa CO Adelphi University Garden City NY Adrian College Adrian MI Adventist University of Health Sciences Orlando FL Agnes Scott College Decatur GA Alabama A & M University Normal AL Alabama State University Montgomery AL Alaska Pacific University Anchorage AK Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Albany NY Albany State University Albany GA Albion College Albion MI Albright College Reading PA Alcorn State University Alcorn State MS Alderson Broaddus University Philippi WV Alfred University Alfred NY Allegheny College Meadville PA Allen University Columbia SC Alma College Alma MI Alvernia University Reading PA Alverno College Milwaukee WI American Indian College of the Assemblies of God Inc Phoenix AZ American International College Springfield MA American Jewish University Los Angeles CA American University Washington DC Amherst College Amherst MA Anderson University Anderson IN Anderson University Anderson SC Andrews University Berrien Springs MI Angelo State University San Angelo TX Anna Maria College Paxton MA Apex School of Theology Durham NC Appalachian State University Boone NC Aquinas College Grand Rapids MI Arcadia University Glenside PA Arizona Christian University Phoenix AZ Arizona State University-Tempe Tempe AZ Arkansas State University-Main Campus Jonesboro AR Arkansas Tech University Russellville AR Art Academy of Cincinnati Cincinnati OH Art Center College of Design Pasadena CA Asbury University Wilmore KY Ashland University -

O:\Ir\All Term Reports\Statsprof15-16.Wpd

2015-2016 STATISTICAL PROFILE INDIANA UNIVERSITY - PURDUE UNIVERSITY FORT WAYNE Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne Institutional Research November, 2015 PREFACE The Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne Statistical Profile is intended to serve as a comprehensive resource about institutional facts and student characteristics. This is the thirty-third year of publication of the Statistical Profile. Many people in various offices have contributed to the development of the information that is presented here. I want to express appreciation for all of their contributions. Your comments and suggestions for improvement of future editions are always welcome. Institutional Research Fort Wayne, Indiana 46805-1499 3 260-481-6375 3 Fax: 260-481-6880 TABLE OF CONTENTS INSTITUTIONAL INFORMATION ............................................ -1- General Officers....................................................... -2- Community Advisory Council ............................................ -3- History of the Fort Wayne Campus........................................ -4- Notable Events........................................................ -6- Undergraduate and Graduate Degree Programs ............................. -11- STUDENT INFORMATION ................................................. -13- Summary of Enrollment by County ....................................... -14- Allen County Student Residence ......................................... -16- Enrollment by State of Residency........................................ -17- Enrollment -

Colleges and Universities with Total Or Partial Smokefree Indoor Air Policies

Defending your right to breathe smokefree air since 1976 U.S. Colleges and Universities with Smokefree and Tobacco-Free Policies July 1, 2012 While it has become relatively common for colleges and universities to have policies requiring that all buildings, including residential housing, be smokefree indoors, this list only includes those colleges and universities with entirely smokefree campuses. + = 100% Tobacco-Free campus (no forms of tobacco allowed). Otherwise policy is smokefree only (other forms of tobacco allowed). There are now at least 774 100% smokefree campuses with no exemptions. Residential housing facilities are included, where they exist. Of these, 562 have a 100% tobacco-free policy. Please note, these policies have been enacted but are not necessarily yet in effect. Please contact the school itself to verify the status of its policy. U.S. States/Territories/Commonwealths Requiring 100% Smokefree College and University Campuses, Indoors and Out (Required 100% Tobacco-Free Campuses Marked +) Below is a list of states/territories/commonwealths that have adopted laws requiring all college and university grounds within the jurisdiction to be 100% smokefree with no exemptions. Arkansas* (33 campuses) Iowa (66 campuses) Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands* (1 campus) Oklahoma* (29 campuses) + *Public institutions only Colleges and Universities with Smokefree Policies: Entire Campus, Indoors and Out (100% Tobacco-Free Campuses Marked +) Below is a list of U.S. colleges and universities that have enacted 100% smokefree campus policies. Alabama Auburn University Wallace State Community College (2 Calhoun Community College (2 campuses) + campuses) + Faulkner University + Alaska Wayland Baptist University + ITT Technical Institute - Bessemer Troy University (4 campuses) Arizona A.T. -

This Booklet Contains a List of Colleges and Universities Submitted to Us By

This booklet contains a list of colleges and universities submitted to us by school administrators to indicate those institutions that have accepted graduates from schools and/or homeschools using the A.C.E. program. It is important to note that students were accepted by these institutions on an INDIVIDUAL basis. Please help us upgrade and/or correct this list. Send your correspondence to: Executive Quality Control Accelerated Christian Education P.O. Box 160509 Nashville, TN 37216 2008 Revision © 1997 Accelerated Christian Education, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced in whole or part in any form or by any means without permission from Accelerated Christian Education, Inc. UNITED STATES ARIZON A (CONTINUED ) Embry Riddle Aeronautical OF AMERICA University AL A B A M A Grand Canyon University Alabama Southern Community International Baptist College College (formerly Patrick Henry Northern Arizona University State Junior College) Pastor’s College of Phoenix Auburn University Southwestern College Bethany Divinity College and University of Arizona Seminary (formerly Bethany ARK A NS A S Theological Seminary and American College of Computer College) Information Services Bishop State Community College Arkansas Bible College Central Alabama Community Arkansas Christian College College (formerly Alexander City Arkansas Community College State Junior College) (formerly West Arkansas Coastal Training Institute Community College) Faulkner State Community College Arkansas Northeastern College Faulkner University Arkansas State University, Gadsden Business College Jonesboro Gadsden State Community College Arkansas State University, Huntingdon College Mountain Home Jacksonville State University Arkansas Tech University Jefferson State Community College American College of Radiology, Lurleen B. -

Financial Aid Information Request Form for the 2018-2019 School Year

Financial aid information request form for the 2018-2019 school year Complete the form ONLY if: Important information for students and parents • The Free Application for Federal from the Indiana Education Savings Authority Student Aid (FAFSA) has been filed and received by the Federal Processor by April 15, 2018; and Did you know… • The account owner is a parent who … that along with all of the tax advantages you can get from a CollegeChoice has completed the 2018-2019 Advisor 529 Savings Plan account, the assets in your account might not affect FAFSA for their child; and the child your student’s chances of receiving state financial aid? is a student planning to attend an Indiana post-secondary institution According to Indiana law, and under certain conditions (see criteria list to the that is eligible* to receive state aid right), the amount of money available in a CollegeChoice Advisor account and for the 2018-2019 year; and is an the proposed use of money in that account on behalf of a beneficiary may not Indiana resident; or be included when determining state grant award eligibility. • The student has completed Since federal law requires that 529 plan assets be included on a FAFSA, the 2018-2019 FAFSA; and is information is needed directly from the account owner and the beneficiary to considered an independent student properly calculate a student’s eligibility. for financial purposes;and is planning to attend an Indiana NOTE: To be considered for the 2018-2019 school year, the CollegeChoice post-secondary institution that is Advisor 529 Savings Plan financial aid information request form must be faxed eligible* to receive state aid for by the deadline of April 15, 2018. -

Section VII Distribution and List of Participating Schools

Section VII Distribution and List of Participating Schools Vice Presidents of Chancellors & State School and Location Adm. & Facilities Total Presidents Survey Survey AK University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau ● Total 0 1 1 AL Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University, Normal ● Athens State University, Athens ● Auburn University, Montgomery ● Auburn University, Auburn ● Calhoun Community College, Decatur ● ● Chattahoochee Valley Community College, Phenix City ● Enterprise-Ozark Community College, Enterprise ● Gadsden State Community College, Gadsden ● J.F. Drake State Technical College, Huntsville ● Jefferson Davis Community College, Brewton ● Spring Hill College, Mobile ● Stillman College, Tuscaloosa ● Troy University, Troy ● ● United States Sports Academy, Daphne ● University of West Alabama, Livingston ● Total 12 5 17 AR Arkansas State University, Newport ● ● Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas, De Queen ● East Arkansas Community College, Forrest City ● Henderson State University, Arkadelphia ● North Arkansas College, Harrison ● NorthWest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville ● Ozarka College, Melbourne ● South Arkansas Community College, El Dorado ● Southern Arkansas University Tech, Camden ● University of Arkansas, Monticello ● University of Arkansas, Pine Bluff ● University of Arkansas Community College, Batesville ● Total 6 7 13 AZ Arizona State University, Tempe ● ● Arizona Western College, Yuma ● Central Arizona College, Coolidge ● Chandler-Gilbert Community College, Chandler ● Coconino County Community -

DWS Thesis List (Chronological)

DWS Thesis List (Chronological) 2002 / 2003 / 2004 / 2005 / 2006 / 2007 / 2008 / 2009 / 2010 / 2011 / 2012 / 2013 / 2014 / 2015 / 2016 / 2017 / 2018 / 2019 /2020 2002 Alford, M. Christopher (2002) Worship, the Church and Contemporary Culture: A Core Course for Master’s Students at the Institute for Worship Studies, Florida Campus ABSTRACT: Monumental change is occurring in worship across our country as we leave the modern era behind and move forward into the unknown element called “postmodern.” The modern, with its emphasis on intellect and word, is slowly but surely being overrun by the postmodern, with its emphasis on experience and symbol. Like the collision of two great landmasses, there will be friction and some earthquakes—perhaps even some fire—but in the end, the steady push of the “new” will make its mark and change the landscape forever. Perhaps the “new” is not so new after all. Many postmodern worshipers, especially youth, are turning for inspiration to the pattern and language of the ancient church. There they are rediscovering classic Christianity and learning to draw strength and spirituality from a deep, satisfying well of time-tested truth and tradition. I am convinced that many of the postmodern world’s thirsts can be marvelously and even uniquely quenched there. This thesis and supporting curriculum advances the idea that the postmodern world has much in common with the world of the first century church. A series of five lectures, together with a number of “Outside the Box” activities and audio-visual supplements, exposes master’s level students to paradigm thinking, the problems with modernity, a basic understanding of postmodernism, and directions for both worship and the church in a postmodern world. -

ED342336.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 342 336 HE 025 310 AUTHOR Kroe, Elaine TITLE Basic Student Charges at Postsecondary Institutions: Academic Year 1990-91. Tuition and Required Fees and Room and Board Charges At 4-Year, 2-Year, and Public Less-than-2-Year Institutions. Statistical Analysis Report. INSTITUTION National Center for Education Statistics (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN-0-16-036129-X; NCES-92-316 PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 163p. AVAILABLE FROMU.S. Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328. PUB TYPE Statistical Data (110) -- Reports - Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Colleges; Community Colleges; *Fees; Higher Education; Instructional Student Costs; Noninstructional Student Costs; Postsecondary Education; Private Colleges; Public Colleges; *Tuition; *Two Year Colleges; *Vocational Schools ABSTRACT This report contains a comprehensive listing of basic student charges for academic year 1990-91 at over 4,700 4-year, 2-year, and public less-than-2-year postsecondary institutions. Typical tuition and required fees are provided for in-state and out-of-state students at the undergraduate and graduate levels, along with the costs for room and board, and the number of meals per week covered by the board charge. Tables give summary national statistics on tuition and required fees for the academic year 1990-91 at postsecondary institutions. Data are also presented on tuition and required fees and room and board charges at individual institutions. These listings are divided into three sections: (1) 4-year institutions (offering a bachelor's degree or higher); (2) 2-year institutions (offering a postsecondary award of at least 2 but less than 4 academic years; and (3) public less-than-2-year institutions (offering a postsecondary award of less than 2 academic years). -

Optionalpdfhardcopy.Pdf

FairTest The National Center for Fair & Open Testing 1,750+ Accredited, 4-Year Colleges & Universities with ACT/SAT-Optional Testing Policies for Fall, 2022 Admissions Current as of September 2021 This list includes bachelor degree granting institutions that do not require recent U.S. high school graduates applying to start classes in fall 2022 to submit ACT/SAT results. As the endnotes indicate, some schools exempt students who meet minimum grade-point average or class rank criteria; others require SAT or ACT scores but use them only for placement purposes. Please check with the school's admissions office for details Sources: College Board 2018 College Handbook; U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges 2020; U.S. A Department of Education Integrated Postsecondary EducationAlma DataCollege System, Alma (IPEDS),, MI admissions office websites; and news reports. Alvernia University, Reading, PA Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College, Tifton, GA Alverno College, Milwaukee, WI Abraham Lincoln University, Glendale, CA AMDA Academy and Conservatory, New York, NY Academy College3, Minneapolis, MN Amberton University, Garland, TX Academy of Art University, San Francisco, CA American Academy of Art, Chicago, IL Academy of Couture Art, West Hollywood, CA American Baptist College, Nashville, TN Adams State University, Alamosa, CO American InterContinental Univ., Multiple Sites Adelphi University, Garden City, NY American International College, Springfield, MA Adrian College, Adrian, MI American Islamic College, Chicago, IL Agnes Scott College, Decatur, -

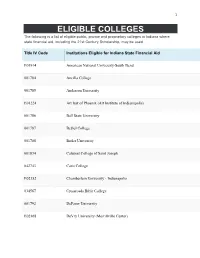

Eligible Colleges

1 ELIGIBLE COLLEGES The following is a list of eligible public, private and proprietary colleges in Indiana where state financial aid, including the 21st Century Scholarship, may be used. Title IV Code Institutions Eligible for Indiana State Financial Aid E01914 American National University-South Bend 001784 Ancilla College 001785 Anderson University E01224 Art Inst of Phoenix (Art Institute of Indianapolis) 001786 Ball State University 001787 Bethel College 001788 Butler University 001834 Calumet College of Saint Joseph 042743 Caris College E02182 Chamberlain University - Indianapolis 034567 Crossroads Bible College 001792 DePauw University E02168 DeVry University (Merrillville Center) 2 Title IV Code Institutions Eligible for Indiana State Financial Aid 001793 Earlham College E01820 Fortis College 001798 Franklin College 001799 Goshen College 001800 Grace College 001801 Hanover College 015227 Harrison College-Anderson 015226 Harrison College-Columbus E01294 Harrison College-Elkhart E00778 Harrison College-Evansville E00931 Harrison College-Fort Wayne 015218 Harrison College-Indianapolis E00777 Harrison College-Indianapolis East 015224 Harrison College-Lafayette E01209 Harrison College-Indianapolis Northwest 3 Title IV Code Institutions Eligible for Indiana State Financial Aid 015220 Harrison College-Terre Haute 007263 Holy Cross College 001803 Huntington University 001805 Indiana Institute of Technology (Fort Wayne/Indianapolis/South Bend) 001807 Indiana State University 001809 Indiana University-Bloomington E01033 Indiana University -

Marion County Corporation of Marion League County

The state of tobacco control Community Partner Minority Partner Minority Partner Minority Partner Lead Minority Partner Lead Agency Lead Agency Lead Agency Agency Lead Agency Health and Hospital Indianapolis Urban Indiana Black Expo, Inc. Indiana Latino Institute Latino Health Organization Marion County Corporation of Marion League County Coordinator: Coordinator: Coordinator: Coordinator: Coordinator: Allison Aultman Janet Kamiri Toni Deaderick Berenice Tenorio Ana Pereira 3833 North Rural St. 777 Indiana Ave. 601 N. Shortridge Rd. 2126 N. Meridian St. 311 N. New Jersey St. Indianapolis, IN 46205 Indianapolis, IN 46202 Indianapolis, IN 46219 Indianapolis, IN 46202 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Ph: (317) 221-3099 Ph: (317) 693-7631 Ph:(317) 923-3111 Ph: (317) 472-1055 Ph: (317) 972-4564 Fx: (317) 221-3114 Fx: (317) 693-7613 Fx: (317) 925-6624 Fx: (317) 472-1056 Fx: (317) 637-0111 AAultman@ [email protected] btenorio@ MarionHealth.org tdeaderick@ indianalatinoinstitute.org [email protected] indianablackexpo.com TOBACCO AND HEALTH IN MARION COUNTY Percent of adults who smoke Smoking and pregnancy Births affected by 1,502 smoking low birth weight, SIDS, reduced lung function Cost of smoking $2.04 million related births Lung cancer deaths per 100,000 residents Percent of pregnant women who smoke Indiana .....................................11.5% Marion County ......................... 9.2% Smoking deaths Cardiovascular disease deaths per 100,000 residents Deaths attributable to smoking 1,541 Deaths due to secondhand smoke 186 Asthma related emergency room visits per 10,000 residents Economic burden of secondhand smoke: $301.8 million Smoking related illness 46,232 TOBACCO CONTROL FUNDING $6.1 billion $1,554,000 Economic cost in Indiana due to smoking. -

Colleges That Require ACT Essay.Xlsx

Colleges That Require ACT Essay Updated April 2017 STATE SCHOOL REQUIRED RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL Texas Abilene Christian University x New York Adelphi University x Georgia Agnes Scott College x Alabama Alabama A&M University x Alaska Alaska Pacific University x New York Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences x Michigan Albion College x Mississippi Alcorn State University x Pennsylvania Allegheny College x Ohio Allegheny Wesleyan College x South Carolina American College of the Building Arts x Indiana American Conservatory of Music x Washington, DC American University x Massachusetts Amherst College x Indiana Anderson University x Michigan Andrews University x Maryland Antietam Bible College x North Carolina Appalachian State University x Arizona Arizona State University—Tempe x Texas Arlington Baptist College x Georgia Armstrong State University x Colorado Art Institute of Colorado x Texas Art Institute of Houston x Indiana Art Institute of Indianapolis x 1 Colleges That Require ACT Essay Updated April 2017 STATE SCHOOL REQUIRED RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL Nevada Art Institute of Las Vegas x Ohio Art Institute of Ohio x Washington Art Institute of Seattle x Minnesota Art Institutes International Minnesota x Iowa Ashford University x Massachusetts Atlantic Union College x Alabama Auburn University x Minnesota Augsburg College x Illinois Augustana College x Texas Austin College x Florida Ave Maria University x Massachusetts Babson College x Michigan Baker College at Allen Park x Michigan Baker College Online x Ohio Baldwin Wallace University