Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan 2017 – 2037

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Walker, Martyn Solid and practical education within reach of the humblest means’: the growth and development of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes 1838–1891 Original Citation Walker, Martyn (2010) Solid and practical education within reach of the humblest means’: the growth and development of the Yorkshire Union of Mechanics’ Institutes 1838–1891. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/9087/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ ‘A SOLID AND PRACTICAL EDUCATION WITHIN REACH OF THE HUMBLEST MEANS’: THE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE YORKSHIRE UNION OF MECHANICS’ INSTITUTES 1838–1891 MARTYN AUSTIN WALKER A thesis -

Exhibition Road Cultural Group (2123).Pdf

To: Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London New London Plan GLA City Hall London Plan Team Post Point 18 London SE1 2AA We welcome the opportunity to comment on the New London Plan and would be grateful if you could confirm receipt of this reponse. About us: The World’s First Planned Cultural Quarter Shared history and mission The Exhibition Road Cultural Group is a partnership of 18 leading cultural and educational organisations in and around Exhibition Road, South Kensington. Together these organisations comprise the world’s first planned cultural quarter, half of which falls within the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Area. Created from the legacy of the Great Exhibition of 1851, and affectionately known as “Albertopolis”, this cultural quarter was established by the Royal Commission for the Great Exhibition of 1851 for the purpose of “increasing the means of industrial education and extending the influence of science and art upon productive industry”. Across its estate of 87 acres in South Kensington, the Royal Commission established three of the world’s most popular museums: The Natural History Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum and three colleges dedicated to arts, science and design: Imperial College London, the Royal College of Music and Royal College of Art and the most famous concert venue in the world, the Grade l listed Royal Albert Hall which was created originally as the Central Hall of Arts and Sciences. Over past century and a half, these institutions have been joined by other organisations that share the mission of promoting innovation and learning through the arts and science, including the Goethe Institut, Royal Geographical Society, Institute Français and the Ismaili Centre. -

Ifield Road, SW10 £1,725,000 Leasehold

Ifield Road, SW10 £1,725,000 Leasehold Ifield Road, SW10 A delightful four-bedroom, period maisonette boasting neutral decor with bright and spacious rooms throughout. Further comprising kitchen, double- reception, guest wc, two en-suites and family bathroom. Ifield Road is superbly positioned on a charming residential road and ideally situated moments from trendy Fulham Road with a wide selection of restaurants, cafes and multi screened cinema, while King's Road is nearby for more extensive shopping. Transport is provided by nearby Earl’s Court, West Brompton and Fulham Broadway stations. Benefitting from close proximity to a host of top performing schools, including Bousfield primary, The London Oratory and Servite RC. Offered with no onward chain. Lease: 125 years Current Service/Maintenance Charge: To be advised - £ per annum Ground Rent: To be advised - £ per annum EPC Rating: E Current: 40 Potential: 48 £1,725,000 Leasehold 020 8348 5515 [email protected] An overview of Kensington & Chelsea The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea is a West London borough of Royal Borough status. It is an urban area, one of the most densely populated in the United Kingdom. The borough is immediately to the west of the City of Westminster and to the east of Hammersmith & Fulham. It contains major museums and universities in "Albertopolis", department stores such as Harrods, Peter Jones and Harvey Nichols and embassies in Belgravia, Knightsbridge and Kensington Gardens, and it is home to the Notting Hill Carnival, Europe's largest. It contains many of the most expensive residential districts in London and even in the world. -

In South Kensington, C. 1850-1900

JEWELS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM: GENDERED AESTHETICS IN SOUTH KENSINGTON, C. 1850-1900 PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK PH.D. HISTORY OF ART UCL 2 I, PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ______________________________________________ 3 ABSTRACT Several collections of brilliant objects were put on display following the opening of the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1881. These objects resemble jewels both in their exquisite lustre and in their hybrid status between nature and culture, science and art. This thesis asks how these jewel-like hybrids – including shiny preserved beetles, iridescent taxidermised hummingbirds, translucent glass jellyfish as well as crystals and minerals themselves – functioned outside of normative gender expectations of Victorian museums and scientific culture. Such displays’ dazzling spectacles refract the linear expectations of earlier natural history taxonomies and confound the narrative of evolutionary habitat dioramas. As such, they challenge the hierarchies underlying both orders and their implications for gender, race and class. Objects on display are compared with relevant cultural phenomena including museum architecture, natural history illustration, literature, commercial display, decorative art and dress, and evaluated in light of issues such as transgressive animal sexualities, the performativity of objects, technologies of visualisation and contemporary aesthetic and evolutionary theory. Feminist theory in the history of science and new materialist philosophy by Donna Haraway, Elizabeth Grosz, Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti inform analysis into how objects on display complicate nature/culture binaries in the museum of natural history. -

Deux Chevaux Press Release19may

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ______________________________________________________________ Deux Chevaux | William Mackrell Performance Date: Saturday 21 June 2014, 11.30am – 6.00pm The performance will be followed by a reception at Andipa Gallery, Knightsbridge, 6.00pm. Deux Chevaux is a performance by William Mackrell consisting of two horses pulling a two-horse power car (Citroen 2CV) through the Royal Borough of Kensington & Chelsea and Westminster, stopping at nine local cultural landmarks on the 21st June 2014. The work challenges the interaction of human and mechanical power, questioning language’s ability to measure their differences and similarities and asks what happens to this action when confronted with the unexpected in the everyday. This is the first time Deux Chevaux is being presented as a public performance. The project’s visual impact aims to instantly engage with a wide audience in major public spaces, presenting the absurdity of the task as both poetic spectacle and serious critique. The event will follow a planned route (please see the performance timetable below) travelling through the ‘Albertopolis’ to the local museums and cultural centres. ‘Albertopolis’ is the unique cultural estate that spans over 87 acres of land in South Kensington. The name came into being, following the Great Exhibition of 1851 held at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park. Organised by Prince Albert, the Great Exhibition successfully raised the necessary funds through public funding to buy the surrounding land and establish the museums, cultural and scientific centres that continue to define the area today. Deux Chevaux aims to engage with this historical context, operating on the crossover between art, nature and science as a site-specific intervention, which embraces Prince Albert’s ambition to, ‘increase the means of industrial education and extend the influence of science and art upon productive industry’. -

Store Listings

STORE LISTINGS STORES STORE ADDRESS DELIVERY ADDRESS TEL/FAX MANAGER & (if different) DIRECT EMAIL (if applicable) FREESTANDING STORES 002-PICCADILLY 170 Piccadilly T: 020 7493 4138 John Ruston – Manager London F: 020 7629 1188 [email protected] [email protected] W1J 9EJ 006-BLUEWATER Case Case London Ltd T/F: 01322 624242 Daniel Painter – Manager Unit 055 Upper Level Service Yard 7 [email protected] South Mall Upper Thames Walk Lisa Gower – Assist. Manager Bluewater Shopping Centre Bluewater Shopping Centre Kent Greenhithe DA9 9SQ Kent DA9 9SQ CONCESSIONS 008-HARVEY NICHOLS LEEDS Case Luggage Concession T/F: 0113 2469638 Ian Leedham – Manager Harvey Nichols [email protected] [email protected] 4th Floor, 107-111 Briggate Leeds David Williamson – Assist. Manager LS1 6AZ 010–HARVEY NICHOLS Case Luggage Concession Case Luggage Concession T: 0161 828 8861 Steven Holmes - Manager MANCHESTER Harvey Nichols Harvey Nichols 1st Floor Loading Bay 21 New Cathedral Street 21 New Cathedral Street [email protected] Manchester Manchester M1 1AD M1 1AD 018-HOOPERS TUNBRIDGE WELLS Case Luggage Concession T: 01892 530222 Nicholas Wardle – Manager Hooper’s [email protected] 2-12 Mount Pleasant Road Tunbridge Wells Kent TN1 1QT July 2015 STORES STORE ADDRESS DELIVERY ADDRESS TEL/FAX MANAGER & (if different) DIRECT EMAIL (if applicable) 030-SELFRIDGES OXFORD ST 400 Oxford Street Exel, Hams Hall Distribution Park, T: 0800 123400 Ext 13815 Suzan Ebanks - Manager London Edison Road, Coleshill, T/F: 020 7495 2027 [email protected] W1A 1AB Birmingham Bogna Filoda – Assist. Manager B46 1DA 040-HARRODS Luggage Department 2nd Floor Case Travel Goods Dept. -

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY of PAPERS

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 76 Summer 2019 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Dr Peter J T Morris Dr Christopher J Cooksey (Watford, 5 Helford Way, Upminster, Essex RM14 1RJ Hertfordshire) [e-mail: [email protected]] Prof Alan T Dronsfield (Swanwick) Secretary: Prof. John W Nicholson Dr John A Hudson (Cockermouth) 52 Buckingham Road, Hampton, Middlesex, Prof Frank James (Royal Institution) TW12 3JG [e-mail: [email protected]] Dr Michael Jewess (Harwell, Oxon) Membership Prof Bill P Griffith Dr Fred Parrett (Bromley, London) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, Prof Henry Rzepa (Imperial College) London, SW7 2AZ [e-mail: [email protected]] Treasurer: Prof Richard Buscall Exeter, Devon [e-mail: [email protected]] Newsletter Dr Anna Simmons Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail: [email protected]] Newsletter Dr Gerry P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail: [email protected]] https://www.qmul.ac.uk/sbcs/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/historical/ 1 Contents From the Editor (Anna Simmons) 2 RSC HISTORICAL GROUP JOINT AUTUMN MEETING 3 William Crookes (1832-1919) 3 RSC HISTORICAL GROUP NEWS 4 Secretary’s Report for 2018 (John Nicholson) 4 MEMBERS’ PUBLICATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS OF INTEREST 4 NEWS FROM CATALYST (Alan Dronsfield) 5 FORTHCOMING EXHIBITIONS 6 SOCIETY NEWS 6 OTHER NEWS 6 SHORT ESSAYS 7 How Group VIII Elements Posed a Problem for Mendeleev (Bill Griffith) 7 Norium, Mnemonics and Mackay (William. -

Architectural Tour of Exhibition Road and 'Albertopolis'

ARCHITECTURAL TOUR OF EXHIBITION ROAD AND ‘ALBERTOPOLIS’ The area around Exhibition Road and the Albert Hall in Kensington is dominated by some of London’s most striking 19th- and 20th-century public buildings. This short walking tour is intended as an introduction to them. Originally this was an area of fields and market gardens flanking Hyde Park. In 1851, however, the Great Exhibition took place in the Crystal Palace on the edge of the park. It was a phenomenal success and in the late 1850s Exhibition Road was created in commemoration of the event. Other international exhibitions took place in 1862 and 1886 and although almost all the exhibition buildings have now vanished, the institutions that replaced them remain. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, had a vision of an area devoted to the arts and sciences. ‘Albertopolis’, as it was dubbed, is evident today in the unique collection of colleges and museums in South Kensington. Begin at Exhibition Road entrance of the V&A: Spiral Building, V&A, Daniel Libeskind, 1996- The tour begins at the Exhibition Road entrance to the V&A, dominated now by a screen erected by Aston Webb in 1909 to mask the original boiler house yard beyond. Note the damage to the stonework, caused by a bomb during the Second World War and left as a memorial. Turn right to walk north up Exhibition Road, 50 yards on your right is the: Henry Cole Wing, V&A, Henry Scott with Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave, 1868-73 Henry Cole was the first director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). -

Sustainability Report

Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan 2017 – 2037 Sustainability Report November 2017 Sustainability Report 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 METHODOLOGY 4 BASELINE CONDITIONS 5 KEY SUSTAINABILITY ISSUES 14 ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS OF NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN POLICIES 19 OVERALL CONCLUSION 68 Appendix A: Objectives of the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan compared with the strategic objectives of the Westminster City Plan (November 2016) Appendix B: Summary of relevant plans and programmes Appendix C: Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Appendix D: Assessment of effects of Neighbourhood Plan Policies © 2017 Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Forum Limited Sustainability Report 2 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Sustainability Report has been prepared to support the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Forum’s (the Forum, KNF or Neighbourhood Forum) Basic Conditions Statement. It demonstrates how the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Plan (the KNP, Neighbourhood Plan or Plan) contributes towards the achievement of sustainable development. 1.2 Sustainable development is about ensuring a better quality of life for everyone, now and for generations to come. It is about considering the long-term environmental, social and economic issues and impacts in an integrated and balanced way. The UK Government has set five guiding principles to achieve the sustainable development purpose. These principles form the basis for policy in the UK and are as follows: • Living within environmental limits • Ensuring a strong, healthy and just society • Building a strong, stable and sustainable economy • Promoting good governance • Using sound science responsibly 1.3 One of the means by which sustainable development can be achieved is through the land-use planning process. 1.4 The Plan can help to achieve sustainable development as it aims to ensure that development meets the needs of people living and working in the Knightsbridge Neighbourhood Area (the Area, KNA or Neighbourhood Area) while at the same time helping to ensure that adverse environmental impacts are minimised. -

Open Call: New Growth on Exhibition Road the Commission

Open Call: New Growth on Exhibition Road Ariel view of Exhibition Road during Great Exhibition Road Festival 2019. Photo credit Thomas Angus. 1 The commission The London Festival of Architecture (LFA), Discover South Kensington and the V&A are collaborating with wider stakeholders to commission a series of installations using regenerative design principles on Exhibition Road this summer through to October, in the lead up to COP26 hosted by the UK in November 2021. We are inviting architects, designers and artists to submit a design proposal for an installation that celebrates and demonstrates how biodiversity and ecology can be embedded in the public realm along Exhibition Road, while also showcasing the role design has to play in the multifaceted challenge of climate change. Following the competition process, three winning teams will be confirmed in May, and awarded £20,000, including a design fee of £3,000, to work with the V&A, Goethe-Institute, and the Science Museum, on developing a fully costed, feasible design. The delivered schemes will be revealed in late July and will remain in-situ for 3 months, in the lead up to COP26 in November. This will be a chance to participate in a unique project and showcase your imaginative design to the public and the many festival producers involved. This initiative is supported by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851. 2 The Context London’s arts and science district is looking forward to welcoming people back this summer. The pioneering Exhibition Road shared space scheme was designed by architects Dixon Jones and completed in 2011. -

South Kensington Pedestrian Tunnel Design Competition 2014

South Kensington Pedestrian Tunnel Design Competition 2014 1 A student ideas competition launched by the Royal The winning design concepts were selected as an Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 and Exhibition approaches that will encourage debate and discussion. Road Cultural Group to re-imagine the South It is anticipated that the winning group will work Kensington Pedestrian Tunnel in South Kensington: with the Exhibition Road Cultural Groups, Transport an important and much-used public space for London and other local stakeholders to develop in London, and the threshold to the area’s cultural the designs further to contribute to planned and educational institutions. improvements to South Kensington station. Entries consisted of cross-disciplinary teams of post-graduate students from the academic Competition Jury institutions within South Kensington: the Royal Sir Christopher Frayling (Chair) – 1851 Royal College of Art, Royal College of Music and Imperial Commissioner & former Rector, Royal College of Art College, looking to harness the energy of today’s Sophie Andreae – Heritage & Architectural Adviser student cohort to create a lively and beautiful space Chris Cotton – CEO, Royal Albert Hall & Chair, that expresses the spirit of the South Kensington Exhibition Road Cultural Group community, and provides a fitting welcome to the Louise Fitton – Head of Content Production, area. The competition builds on a tradition of giving Natural History Museum local students the opportunity to contribute to public William Jackson, Chair of -

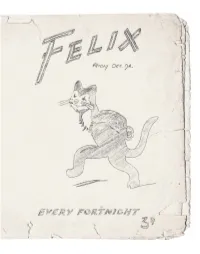

WRAP 1&4 Front Front and Back.Indd

2 felix FRIDAY 09 DECEMBER 1949 Extracts from the first issue of Felix, published on the 9th of December, 1949 The need has been felt for some time for a frequently published journal to comment upon the affairs of the College whilst they are still topical, and to bring to the attention of its members the activities of Clubs and Societies of which people at present know little, and knowing little, tend to care even less. This is a function which clearly cannot be performed by THE PHOENIX, particularly since that estimable bird is now to appear only twice a year, and so FELIX has come to meet the need. We do not intend to encroach upon the literary field covered by THE PHOENIX; rather do we intend to be complementary to that journal, even if not always complimentary. Neither are we in any way connected with it, nor are we its offspring. (In any case, this unfortunate bird is presumably unable to produce any offspring, since only one bird exists at any one time, rising from the ashes of its predecessor. Perhaps this accounts for its doleful appearance). No, THE PHOENIX will remain an essentially literary magazine, whereas we shall content ourselves with providing a commentary upon events and personalities. The success or failure of this paper depends principally upon you, our readers. In the first place we depend upon you to produce many of our articles and reports, since our staff cannot themselves attend and report every College event. Secondly we depend upon you to maintain a lively correspondence in our columns.