An Overview of the Pine Wood Nematode Ban in North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monochamus Spp.: Insect Vectors of Bursaphelenchus Xylophilus

November 2015 Monochamus spp.: insect vectors of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus Longhorned beetles of the genus Monochamus spp. are vectors of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (PWN) that may cause the death of pine trees. In the EPPO region, PWN has established in continental Portugal, where the main vector is Monochamus galloprovincialis. Beetles of Monochamus emerging from PWN-infested trees/wood are able to carry PWN and transmit it to non-infested trees during maturation feeding. Theoretically, hitchhiking beetles could present a risk of introducing PWN to new areas/countries but information on hitchhiking Monochamus is missing. Information is missing on the vectors of the genus Monochamus, in particular data on flight distances and total dispersal over the lifetime of the adult beetle but also about the best methods for monitoring. In case of introduction of pinewood nematode in a new country, this information is indispensable for risk assessment and emergency measures. The project will gather and process available information for best prediction of damage risk of Monochamus spp. Five countries and seven institutions participate in this project: Portugal, Slovenia, Belgium, The Nertherlands and Denmark. These countries are different in status with respect to both the presence of Monochamus spp. and of pinewood nematode. The project’s main results include: . Best monitoring strategies for Monochamus spp. Mapping of PWN and occurrence of native Monochamus species across Europe . Phenology studies of Monochamus spp., prevalence of nematodes in longhorned beetles and dispersal studies of M. galloprovincialis . Identification of factors that lead to variations in expression of disease due to Bursaphelencus spp. in different regions of Europe . -

Pine Wilt Rapid Wilting and Death of Pine

Pine Wilt Rapid wilting and death of pine Pathogen—The pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, causes pine wilt disease. Nematodes are “roundworms” in the phylum Nematoda, which has over 80,000 described species. This disease can be a problem wher- ever non-native pines are planted but is most common in Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota. Vectors—The pine sawyer beetles, Monochamus spp., transmit the nematode. Please see the Roundheaded Wood Borers (Longhorned Beetles) entry in this guide for more information. Hosts—Scots, Austrian, and other non-native pines are often killed by this disease. Eastern white pine, a native pine, is also affected and may be killed by pine wilt disease. The nematode commonly infects other native pines and some native conifer species. However, most native species are resistant to the disease (e.g., native conifers may be infected and express little or no disease Figure 1. Symptoms of pine wilt disease symptoms). on Austrian pine branch. Photo: North Cen- tral Research Station Archive, USDA Forest Signs and Symptoms—As with many wilts, signs are microscopic. The Service, Bugwood.org. pine wood nematode is relatively large compared with other nema- todes, but it cannot be seen with a hand-lens in infected wood. Laboratory tests are required to confirm its presence. Pine wilt disease causes rapid wilting and death on non-native pines. Symptoms are often first expressed in early summer but can occur throughout the growing season. Symptoms may first appear on one or a few branches but often develop quickly throughout the crown, and trees may die only 1 or 2 months after symptoms appear. -

Red Ring Disease of Coconut Palms Is Caused by the Red Ring Nematode (Bursaphelenchus Cocophilus), Though This Nematode May Also Be Known As the Coconut Palm Nematode

1 Red ring disease of coconut palms is caused by the red ring nematode (Bursaphelenchus cocophilus), though this nematode may also be known as the coconut palm nematode. This disease was first described on coconut palms in 1905 in Trinidad and the association between the disease and the nematode was reported in 1919. The vector of the nematode is the South American palm weevil (Rhynchophorus palmarum), both adults and larvae. The nematode parasitizes the weevil which then transmits the nematode as it moves from tree to tree. Though the weevil may visit many different tree species, the nematode only infects members of the Palmae family. The nematode and South American palm weevil have not yet been observed in Florida. 2 Information Sources: Brammer, A.S. and Crow, W.T. 2001. Red Ring Nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus (Cobb) Baujard (Nematoda: Secernentea: Tylenchida: Aphelenchina: Aphelenchoidea: Bursaphelechina) formerly Rhadinaphelenchus cocophilus. University of Florida, IFAS Extension. EENY236. Accessed 11-27-13 http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in392 Griffith, R. 1987. “Red Ring Disease of Coconut Palm”. The American Pathological Society Plant Disease, Volume 71, February, 193-196. accessed 12/5/2013- http://www.apsnet.org/publications/plantdisease/ba ckissues/Documents/1987Articles/PlantDisease71n02_193.PDF Griffith, R., R. M. Giblin-Davis, P. K. Koshy, and V. K. Sosamma. 2005. Nematode parasites of coconut and other palms. M. Luc, R. A. Sikora, and J. Bridges (eds.) In Plant Parasitic Nematodes in Subtropical and Tropical Agriculture. C.A.B. International, Oxon, UK. Pp. 493-527. 2 The host trees susceptible to the red ring nematode are usually found in the family Palmae. -

Pine Sawyer Beetle, Monochamus Galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Géraldine Roux, Julien Haran, Alain Roques, Christelle Robinet

Pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Géraldine Roux, Julien Haran, Alain Roques, Christelle Robinet To cite this version: Géraldine Roux, Julien Haran, Alain Roques, Christelle Robinet. Pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). ICE 2016; XXV International Congress of Entomology, Sep 2016, Orlando, United States. 10.1603/ICE.2016.92731. hal-01603686 HAL Id: hal-01603686 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01603686 Submitted on 5 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License 0501: Pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Monday, September 26, 2016 03:45 PM - 04:00 PM Convention Center - Room W224 A Species in the worldwide genus Monochamus have drawn particular attention since they vector the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelencus xylophilus, PWN), responsible for pine wilt disease. Although a secondary pest in its native North America, PWN has devastated conifer forests in invaded regions of eastern Asia, and more recently of southwestern Europe, incurring huge management costs to attempt eradication which remains unsuccessful. So far, only one native European species, M. galloprovincialis, has been proven to have developed a novel association with the invasive PWN. -

Chestnut Oak Shortleaf Pine

Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) Chestnut Oak (Quercus prinus) The Need to Know: How Trees Grow Paul Wray Paul Wray Paul Paul Wray Paul Kentucky Forestry Kentucky Forestry The Eastern Red Cedar is actually in the juniper family and is not closely related Although its serrated leaves resemble those of an American chestnut, this tree to other cedars. Its tough, stringy bark and waxy, scaly needles are designed for is actually a species of oak. It is also referred to as rock oak because it likes to survival in very dry conditions. The berries of the red cedar are an important food grow in rocky areas. The bark of a chestnut oak has vertical rectangular chunks. source for many songbirds. The wood is prized by builders for its rich red color, Good acorn crops are infrequent, but when available, the sweet nuts are eaten by sweet smell, and weather-resistant properties. deer, wild turkeys, squirrels and chipmunks. Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) White Oak (Quercus alba) Paul Wray Paul Paul Wray Paul Richard Webb Richard This evergreen shrub can be found in a variety of habitats along Eastern North The leaves of the white oak have rounded lobes, and the bark is light gray and America. It has a gnarled, multi-stemmed trunk with ridged bark, and typically scaly on older trees. The acorns are elongated with a shallow cap, and have a grows as a rounded, dense shrub of 5-15 feet tall. The leaves are broad with sweet taste, which makes them a favorite food for deer, bear, turkeys, squirrels pointed tips, and the mountain laurel’s noteworthy cup-shaped flowers bloom in and other wildlife. -

Morphological, Molecular and Phylogenetic Study of Filenchus

Alvani et al., J Plant Pathol Microbiol 2015, S:3 Plant Pathology & Microbiology http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/2157-7471.S3-001 Research Article Open Access Morphological, Molecular and Phylogenetic Study of Filenchus aquilonius as a New Species for Iranian Nematofauna and Some Other Known Nematodes from Iran Based on D2D3 Segments of 28 srRNA Gene Somaye Alvani1, Esmat Mahdikhani Moghaddam1*, Hamid Rouhani1 and Abbas Mohammadi2 1Department of Plant Pathology, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran 2Department of Plant Pathology, University of Birjand, Birjand, Iran Abstract Ziziphus zizyphus is very important crop in Iran. Because there isn’t any research of plant parasitic nematodes on Z. zizyphus, authors were encouraged to work on it. Nematodes isolated from the soil samples by whitehead method (1965) and permanent slides were prepared. Among the species Filenchus aquilonius is redescribed for the first time from Southern Khorasan province.F. aquilonius is characterized by lip region rounded, not offset, with fine annuls; four incisures in lateral line; Stylet moderately developed, 10-11.8 µm long with rounded knobs; Hemizonid immediately in front of excretory pore; Deirids at the level of excretory pore; Spermatheca an axial chamber and offset pouch; Tail about 120-157 µm, tapering gradually to a pointed terminus. For molecular identification the large subunit expansion segments of D2/D3 were performed for F. aquilonius to examine the phylogenetic relationships with other Tylenchids. DNA sequence data revealed that F. aquilonius had closet phylogenetic affinity withIrantylenchus vicinus as a sister group and with other Filenchus species for this region and placed them in one clade with 100% for bootstap value support. -

Red Ring Nematode, Bursaphelenchus Cocophilus (Cobb

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-236 Red Ring Nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus (Cobb) Baujard (Nematoda: Secernentea: Tylenchida: Aphelenchina: Aphelenchoidea: Bursaphelechina) formerly Rhadinaphelenchus cocophilus1 A. S. Brammer and W. T. Crow2 Introduction In some areas, mainly from Mexico to South America and in the lower Antilles, B. cocophilus is Bursaphelenchus cocophilus causes red ring co-distributed with its primary vector, R. palmarum. disease of palms. Symptoms of red ring disease were The red ring nematode has not yet been reported from first described on Trinidad coconut palms in 1905. the continental U.S., Hawaii, Puerto Rico or the Red ring disease can appear in several species of Virgin Islands (as of 2000). R. palmarum has been tropical palms, including date, Canary Island date and found in Central and South America and east from Cuban royal, but is most common in oil and coconut some of the West Indies to Cuba. palms. The red ring nematode parasitizes the palm weevil Rhynchophorus palmarum L., which is Economic Importance attracted to fresh trunk wounds and acts as a vector for B. cocophilus to uninfected trees. In Trinidad, red ring disease kills 35 percent of young coconut trees. In nearby Tobago, one Distribution plantation lost 80 percent of its coconut trees. Over a 10-year period in Venezuela, 35 percent of oil palms Red ring nematode is found in areas of Central died from red ring disease. In Grenada, 22.3 percent America, South America and many Caribbean of coconut palms was found to be infected. -

Current U.S. Forest Data and Maps

CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA AND MAPS Forest age FIA MapMaker CURRENT U.S. Forest ownership TPO Data FOREST DATA Timber harvest AND MAPS Urban influence Forest covertypes Top 10 species Return to FIA Home Return to FIA Home NEXT Productive unreserved forest area CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA (timberland) in the U.S. by region and AND MAPS stand age class, 2002 Return 120 Forests in the 100 South, where timber production West is highest, have 80 s the lowest average age. 60 Northern forests, predominantly Million acreMillion South hardwoods, are 40 of slightly older in average age and 20 Western forests have the largest North concentration of 0 older stands. 1-19 20-39 40-59 60-79 80-99 100- 120- 140- 160- 200- 240- 280- 320- 400+ 119 139 159 199 240 279 319 399 Stand-age Class (years) Return to FIA Home Source: National Report on Forest Resources NEXT CURRENT U.S. FOREST DATA Forest ownership AND MAPS Return Eastern forests are predominantly private and western forests are predominantly public. Industrial forests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. Timber harvest by county FOREST DATA AND MAPS Return Timber harvests are concentrated in Maine, the Lake States, the lower South and Pacific Northwest regions. The South is the largest timber producing region in the country accounting for nearly 62% of all U.S. timber harvest. Source: National Report on Forest Resources Return to FIA Home NEXT CURRENT U.S. -

"Structure, Function and Evolution of the Nematode Genome"

Structure, Function and Advanced article Evolution of The Article Contents . Introduction Nematode Genome . Main Text Online posting date: 15th February 2013 Christian Ro¨delsperger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Adrian Streit, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany Ralf J Sommer, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Tuebingen, Germany In the past few years, an increasing number of draft gen- numerous variations. In some instances, multiple alter- ome sequences of multiple free-living and parasitic native forms for particular developmental stages exist, nematodes have been published. Although nematode most notably dauer juveniles, an alternative third juvenile genomes vary in size within an order of magnitude, com- stage capable of surviving long periods of starvation and other adverse conditions. Some or all stages can be para- pared with mammalian genomes, they are all very small. sitic (Anderson, 2000; Community; Eckert et al., 2005; Nevertheless, nematodes possess only marginally fewer Riddle et al., 1997). The minimal generation times and the genes than mammals do. Nematode genomes are very life expectancies vary greatly among nematodes and range compact and therefore form a highly attractive system for from a few days to several years. comparative studies of genome structure and evolution. Among the nematodes, numerous parasites of plants and Strikingly, approximately one-third of the genes in every animals, including man are of great medical and economic sequenced nematode genome has no recognisable importance (Lee, 2002). From phylogenetic analyses, it can homologues outside their genus. One observes high rates be concluded that parasitic life styles evolved at least seven of gene losses and gains, among them numerous examples times independently within the nematodes (four times with of gene acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. -

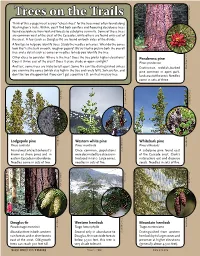

Trees on the Trails D Think of This 4-Page Insert As Your “Cheat Sheet” for the Trees Most Often Found Along Washington’S Trails

trees canreach 300feettall. east of the crest. Old-growth forests drier in and forests rain western both in tree Abundant Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas-fir Needles comeinsetsoftwo. abundance. in Cascades eastern known as shore pine) and in it’s (where crest of west Found Pinus contorta pine Lodgepole WASHINGTON WASHINGTON don’t betoodisappointedifyoucan’tgetapositiveI.D.onthatmysterytree. and fun, have So fall!). rarely and tree the in high stay (which cones the examine you unless distinguished be can’t firs Some apart. tell to tricky are trees some last, And Does itthriveeastofthecrest?craveshadeoropensunlight? elevations? higher prefer tree the Does tree? the is Where consider: to clues Other overall the both picture tree andadetailsuchasconesorneedlestohelpyouidentifythetree. to tried We’ve papery? or rough smooth, bark the Is like? look cones the do What leaves. or needles the Study trees: identify you help to tips few A the crest.Afew(suchasDouglas-fir)arefoundonbothsidesofdivide. of east only found are others while Cascades, the of crest the of west common are trees these of Some summits. subalpine to forests lowland from everywhere found trees deciduous flowering and conifers both find along you’ll Within, found trails. often Washington’s most trees the for sheet” “cheat your as insert 4-page this of Think Trees ontheTrails Trees TRAILS ALAN BAUER ALAN BAUER DAVE SCHIEFELBEIN ALAN BAUER very shadetolerant. below 3,500 feet, this tree is forests westside in Douglas-fir Second only in abundance to heterophylla Tsuga hemlock Western needles insetsoffive. cones, Large 1910. in troduced in disease a by decimated were Once common, populations Pinus monticola pine white Western August 2007 August - SUSAN MCDOUGAL SUSAN MCDOUGAL SYLVIA FEDER SUSAN MCDOUGAL come insetsofthree. -

Northeastern Coastal and Interior Pine-Oak Forest

Northeastern Coastal and Interior Pine-Oak Forest Macrogroup: Northern Hardwood & Conifer yourStateNatural Heritage Ecologist for more information about this habitat. This is modeledmap a distributiononbased current and is data nota substitute for field inventory. based Contact © Maine Natural Areas Program Description: A mixed forest dominated by white pine, red oak, and hemlock in varying proportions. Red maple and white and black oak are common associates, and northern hardwoods like white ash and American beech can appear as minor components. This forest of low to moderate moisture is usually closed canopy and can be heavily coniferous, with some nearly pure stands of white pine and red maple; hemlock is often more abundant in moister settings. This system type occurs over broad areas, but most of it is in early to mid-successional stages and heavily fragmented. It may well be that it is more widespread and abundant as a result of human occupation of and changes to the New State Distribution: CT, MA, ME, NH, RI England landscape. Total Habitat Acreage: 1,538,080 Ecological Setting and Natural Processes: Percent Conserved: 15.8% Usually occurs on flat to rolling glacial landscapes on State State GAP 1&2 GAP 3 Unsecured nutrient-poor, sandy substrates, and is often found near State Habitat % Acreage (acres) (acres) (acres) water or wetlands. Upper elevation limit is about 1000’ to NH 43% 654,780 12,748 89,778 552,254 1200’ (305-365m) in central Massachusetts and southern MA 26% 403,139 9,054 81,076 313,009 New Hampshire, but it is usually considerably lower. -

Chestnut Oak Forest (White Pine Subtype)

CHESTNUT OAK FOREST (WHITE PINE SUBTYPE) Concept: The White Pine Subtype encompasses lower elevation Quercus montana forests that have a significant component of Pinus strobus, which may range from a substantial minority to codominant in the canopy. The lower strata in this subtype appear to overlap the less extreme range of variation of the Dry Heath Subtype and the Herb Subtype. Distinguishing Features: Chestnut Oak Forest (White Pine Subtype) is distinguished from all other communities by the combination of Quercus montana with Pinus strobus, without a component of Quercus alba. The White Pine Subtype subtype should only be used where white pine is believed to be naturally present, not for forests where it has been planted or where it likely spread from nearby plantings. Forests with a more mesophytic composition, such as the forests of Quercus rubra and Pinus strobus with Rhododendron maximum that occur around Linville Falls, are treated as the Mesic Subtype. Synonyms: Pinus strobus - Quercus (coccinea, prinus) / (Gaylussacia ursina, Vaccinium stamineum) Forest (CEGL007519). Ecological Systems: Southern Appalachian Oak Forest (CES202.886). Sites: The White Pine Subtype occurs on open slopes and spur ridges. It often is in steep gorges or in the most rugged foothill ranges. Most example are at 1000-2500 feet elevation, but a few are reported upward to 4000 feet or even higher. Soils: Soils are generally Typic Dystrochrepts, especially Chestnut and Edneyville, less often Typic Hapludults such as Tate or Cowee. Hydrology: Sites are dry and well drained but may be somewhat less stressful because of topographic sheltering. Vegetation: The forest canopy is dominated by a mix of Pinus strobus and Quercus montana, occasionally with Quercus coccinea or Quercus rubra codominant.