Turkey in Somalia: Shifting Paradigms of Aid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Briefing Paper

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso UNHCR Brussels E-mail : [email protected] August 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The classical definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention was ill- suited to the majority of African refugees, who started fleeing in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. These refugees were by and large not the victims of state persecution, but of civil wars and the collapse of law and order. Hence the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention expanded the definition of “refugee” to include these reasons for flight. Furthermore, the refugee-dissidents of the 1950s fled mainly as individuals or in small family groups and underwent individual refugee status determination: in-depth interviews to determine their eligibility to refugee status according to the criteria set out in the Convention. The mass refugee movements that took place in Africa made this approach impractical. As a result, refugee status was granted on a prima facie basis, that is with only a very summary interview or often simply with registration - in its most basic form just the name of the head of family and the family size.1 In the Somali context the implementation of this approach has proved problematic. -

Somalia Energy Sector Needs Assessment and Investment Programme November 2015 Somalia - Energy Sector Needs Assessment and Investment Programme

Somalia Energy Sector Needs Assessment and Investment Programme November 2015 Somalia - Energy Sector Needs Assessment and Investment Programme Copyright © 2015 African Development Bank Group Immeuble du Centre de commerce International d’Abidjan CCIA Avenue Jean-Paul II 01 BP 1387 Abidjan 01, Côte d'Ivoire Phone (Standard): +225 20 26 10 20 Internet: www.afdb.org Rights and Permissions All rights reserved. The text and data in this publication may be reproduced as long as the source is cited. Reproduction for commercial purposes is forbidden. Legal Disclaimer The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report are those of the author/s and are not necessarily those of the African Development Bank. In the preparation of this document, every effort has been made to offer the most current, correct and clearly expressed information possible. Nonetheless, inadvertent errors can occur, and appli - cable laws, rules and regulations may change. The African Development Bank makes its documentation available wi - thout warranty of any kind and accepts no responsibility for its accuracy or for any consequences of its use. Cover design: AfDB Cover photos: Image © AU-UN IST PHOTO/Ilyas A. Abukar; Image © NIGEL CARR ii Somalia - Energy Sector Needs Assessment and Investment Programme Table of contents Foreword v Ackonwledgements vii Abbreviations and acronyms ix Executive summary xi 1. Introduction and background 1 1.1. Introduction 1 1.2. Objectives/scope 3 1.3. Brief description of the current energy sector 3 1.4. Sector organisation and policies 4 1.5. Reliance on the private sector 5 1.6. Four main issues facing Somalia’s energy sector 6 2. -

Tahir, Abdifatah I.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details URBAN GOVERNANCE, LAND CONFLICTS AND SEGREGATION IN HARGEISA, SOMALILAND: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES AND CONTEMPORARY DYNAMICS ABDIFATAH I TAHIR This thesis is submitted to the Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) OCTOBER 1, 2016 DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY SCHOOL OF GLOBAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX 1 | Page ORIGINALITY STATEMENT I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature 2 | Page I. ABSTRACT This thesis offers an explanation for why urban settlement in Somaliland’s capital city of Hargeisa is segregated along clan lines. The topic of urban segregation has been neglected in both classic Somali studies, and recent studies of post-war state-building and governance in Somaliland. Such negligence of urban governance in debates over state-making stems from a predominant focus on national and regional levels, which overlooks the institutions governing cities. -

2010 by Bram Piot

Birding in and around Hargeisa, Somaliland, December 2010 by Bram Piot From December 10 to 17 I stayed in Hargeisa for my work with PSI, a public health NGO that recently established an office in Somaliland. For Saturday 11th I had organised a day out birding with Abdi Jama from NatureSomaliland, who had also guided three groups earlier this year – the first commercial birding tours to visit Somaliland. Our day trip took us east of Hargeisa through thorn bush, acacia woodland, rocky plains and wadis all the way to the vast Tuuyo plain (see map 1). Several very productive stops were made along the first 20 kilometers of the trip; Tuuyo plain was explored in the early afternoon so the birds there was not very active – e.g. none of the larks were singing, but this may also be because it is non-breeding season for most species. Our late lunch stop to the north of Shaarub village proved to be a good spot, but a long drive back to Hargeisa prevented us from fully exploring this area or the plains that we crossed further to the north (Qoryale for example looked pretty good). On hindsight, it probably would have been more efficient (less driving, more birding!) to drive back the way we came, rather than doing the long loop towards the Hargeisa-Berbera tarmac road. Total trip distance was about 280 km. Nearly 100 species were recorded during this day trip, with personal highlights including 3 species of Bustard (Little Brown, Heuglin’s, Buff-crested), several confiding Somali and Double- banded Coursers, a Greyish Eagle-Owl, 6 lark species including the endemic Lesser Hoopoe and Sharpe’s Larks, an Arabian Warbler, several Golden-breasted Starlings, a Three-streaked Tchagra, Rosy-patched Bush-shrikes, Somali Wheatears, Somali Bee-eaters, a group of Scaly Chatterers, etc. -

Hargeisa, Somaliland – Invisible City David Kilcullen

FUTURE OF AFRICAN CITIES PROJECT DISCUSSION PAPER 4/2019 Hargeisa, Somaliland – Invisible City David Kilcullen Strengthening Africa’s economic performance Hargeisa, Somaliland – Invisible City Contents Executive Summary .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Key Facts and Figures .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Invisible City .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 Clan and Camel .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 Observations on urban-rural relations .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 Diaspora and Development .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11 Observations on Banking, Remittances and Financial Transfers .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 A Two-Speed City .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 Observations on Utilities and Critical Infrastructure .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 The Case for International Recognition .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 Observations on International Recognition .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 20 Ports and bases .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Human Capital .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 22 The Diaspora ‘Brain Gain’ .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. . -

2.6 Million 400,000

SOMALIA MISSION UPDATE #9 COVID-19 Preparedness and Response 17 May - 23 May 2020 SITUATION OVERVIEW 1,689 The humanitarian crisis in Somalia, characterized by both natural and man-made CONFIRMED CASES1 factors, is one of the most complex and longstanding emergencies in the world. Somalia is currently facing Locust crisis, whilst simultaneously entered the Gu rainy season, with many areas recording more than twice their average rainfall, causing floods across Somalia affecting a million people and displacing over 400,000 people. With 2.6 million displaced persons, COVID-19 poses an additional challenge in already fragile context where it may further hinder access to basic services, leaving 2.6 million the population highly vulnerable. DISPLACED PERSONS2 As a key source, transit and, to some extent, destination country for migratory flows, Somalia continues to have an influx of migrants from neighboring countries through irregular migration routes, especially from Ethiopia. Hundreds of migrants are stranded in Bossaso as a result of border and sea-crossing closures brought on by the 400,000 COVID-19 pandemic. IOM data show that migration in the Eastern route is still taking NEWLY DISPLACED DURING place despite the new border restrictions in the region. While more people continue GU RAINY SEASON to arrive in Bossaso, higher number of Ethiopian migrants are stranded in the city. IOM estimates that nearly 400 migrants are currently hosted by members of the Ethiopian community living in informal settlements around the city. Recognizing that 11 March 2020 mobility is a determinant of health and risk exposure, there is a need to urgently adopt innovative, systematic, multisectoral and inclusive responses to mitigate, prepare for WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic and respond to COVID-19 amongst the migrant population. -

Pre-Feasibility Study of the Regional Transport Sector in the Berbera Corridor Final Pre-Feasibility Report

TTHHEE EEUURROOPPEEAANN CCOOMMMMIISSSSIIOONN DDEELLEEGGAATTIIIOONN OOFF TTHHEE EEUURROOPPEEAANN CCOOMMMMIIISSSSIIIOONN IIINN KKEENNYYAA PPRREE--FFEEAASSIIIBBIIILLIIITTYY SSTTUUDDYY OOFF TTHHEE RREEGGIIIOONNAALL TTRRAANNSSPPOORRTT SSEECCTTOORR IIINN TTHHEE BBEERRBBEERRAA CCOORRRRIIIDDOORR FFIIINNAALL PPRREE--FFEEAASSIIIBBIIILLIIITTYY RREEPPOORRTT EEXXEECCUUTTIIIVVEE SSUUMMMMAARRYY In collaboration with LOUIS BERGER S.A. AFROCONSULT Mercure III Wereda 2 Kalebe 14 H.N. 002 55 bis quai de Grenelle Ayu Sashe Building 75015 Paris - France Addis Ababa, Ethiopia September 2003 Louis Berger S.A. and Afro-Consult P.l.c This report was produced by Louis Berger S.A. and Afro-Consult P.l.c for the European Commission’s Delegation in Kenya and represents solely their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European Commission’s services. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Pre-Feasibility Study of the Regional Transport Sector in the Berbera Corridor Final Pre-Feasibility Report Louis Berger S.A. and Afro-Consult Plc EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Louis Berger S.A. was commissioned by the Delegation of the European Commission in Kenya to carry out the pre-feasibility study of the regional transport sector in the Berbera corridor, Afro-Consult P.l.c. from Ethiopia is a sub-contractor to Louis Berger S.A. for this study. This assignment is financed under the 8th European Development Fund. The Pre-feasibility study of the transport sector of the Berbera corridor (here-after called “the Study”) compares it with the other routes from Ethiopia to regional seaports (Djibouti, Assab, Massawa, Mombasa and Port Sudan) in order to determine the potential viability of investments to upgrade its main components : • The port of Berbera • The unimproved sections of the road between Berbera and Addis Ababa • The Hargeisa and Berbera airports. -

KOD FLYGPLATS AAC Al Arish, Egypt

KOD FLYGPLATS AAC Al Arish, Egypt – Al Arish Airport AAM Mala Mala Airport AAN Al Ain, United Arab Emirates – Al Ain Airport AAQ Anapa Airport – Russia AAT Altay, China – Altay Airport AAX Araxa, Brazil – Araxa Airport ABC Albacete, Spain – Albacete Airport ABE Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton International, PA, USA ABK Kabri Dar, Ethiopia – Kabri Dar Airport ABL Ambler, AK, USA ABM Bamaga, Queensland, Australia ABQ Albuquerque, NM, USA – Albuquerque International A ABR Aberdeen, SD, USA – Aberdeen Regional Airport ABS Abu Simbel, Egypt – Abu Simbel ABT Al-Baha, Saudi Arabia – Al Baha-Al Aqiq Airport ABV Abuja, Nigeria – Abuja International Airport ABX Albury, New South Wales, Australia – Albury ABY Albany, GA, USA – Dougherty County ABZ Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom – Dyce ACA Acapulco, Guerrero, Mexico – Alvarez International ACC Accra, Ghana – Kotoka ACE Lanzarote, Canary Islands, Spain – Lanzarote ACH Altenrhein, Switzerland – Altenrhein Airport ACI Alderney, Channel Islands, United Kingdom – The Bl ACK Nantucket, MA, USA ACT Waco, TX, USA – Madison Cooper ACV Arcata, CA, USA – Arcata/Eureka Airport ACY Atlantic City /Atlantic Cty, NJ, USA – Atlantic Ci ADA Adana, Turkey – Adana ADB Izmir, Turkey – Adnan Menderes ADD Addis Ababa, Ethiopia – Bole ADE Aden, Yemen – Aden International Airport ADJ Amman, Jordan – Civil ADK Adak Island, Alaska, USA, Adak Island Airport ADL Adelaide, South Australia, Australia – Adelaide ADQ Kodiak, AK, USA ADZ San Andres Island, Colombia AED Aleneva, Alaska, USA – Aleneva Airport AEP Buenos Aires, Buenos -

Small Arms in Somaliland: Their Role and Diffusion

BITS Research Report 99.1 March 1999 Ekkehard Forberg Ulf Terlinden Small Arms in Somaliland: Their Role and Diffusion Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS) Small Arms in Somaliland: Their Role and Diffusion Ekkehard Forberg and Ulf Terlinden work as research assistants at the Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS). They both study Political Science at the "Free University of Berlin". Contact: [email protected] [email protected] The Report is published by the Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS). All rights reserved by the authors. March 1999 ISBN 3-933111-01-3 ISSN 1434-3258 The Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS) is an independent research organisation analysing international security issues. The BITS-Förderverein e.V. is a tax exempt non-profit organisation under German laws. Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS) Rykestr. 13 BITS has published reports on a range D-10405 Berlin of issues in security policy and Germany disarmament. Please get in touch with ph. +49 30 4468 58-0 BITS if you are interested in further fax +49 30 4410-221 information. [email protected] BITS Research Report 99.1 March 1999 Ekkehard Forberg Ulf Terlinden Small Arms in Somaliland: Their Role and Diffusion Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security (BITS) STRUCTURE PREFACE................................................................................................................. 9 1. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................ -

Somaliland Security at the Crossroads: Pitfalls and Potentials

American International Journal of Contemporary Research Vol. 4, No. 7; July 2014 Somaliland Security at the Crossroads: Pitfalls and Potentials Nasir M. Ali A Researcher Currently Enrolling a Postgraduate Program Center for African and Oriental Studies Addis Ababa University Ethiopia Abstract This study examines the peace and stability of Somaliland and how a once the improving security has declined due to the contribution of various factors such as the dramatic decline of the cooperation on security and other related matters with bilateral partners not only in the region, but also beyond, and the unity of the Somaliland citizens which was the cornerstone of the state security which is fading under the leadership of Silanyo. The study also examines the challenges that face the security of Somaliland from within and its implications to the regional security and stability. The study has chosen to examine the nexus between three separate, but interrelated factors which require clear and informed thinking of the day: geoposlitics and vulnerability of the region and the threat posed by the global war on ‘terrorism’, weak leadership style and presence of Islamist elements within the Somaliland’s decision-making circles, hollowed-out institutions and high-level, pervasive corruption. The study connects the security of Somaliland with the stability for the wider region, which has great implications both on the human and state securities. The study argues that the jihadi surge in Somalia, which is the tragic, violent outcome of steadily deteriorating political dynamics since the state collapse in 1991 and conquered many parts of south–central Somalia reveal the fragility of the Horn African region. -

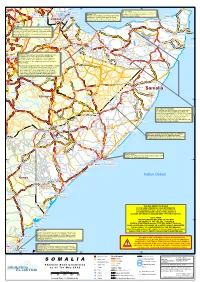

Somalia S O M a L

o o (o! (o! ! (! (o! ! o o ! ! Lalibela Elidahar OBOCK Caluula o (o! 40°E o 44°E 48°E (! ! ( o (! TADJOURAH MOUo CHA Bossasso Port Weldiya DUBTI o The port is busy. Two livestock vessels are at anchorage, o DJIBOUTI Djibouti o h Berbera Port waiting to berth. Berthing priority continues to be on a o! ! ! o ( ASAITA WEST Asaita .! The port is not congested. Several dhows are at berth, Qandala o!o!! AMBOULI first-come, first served basis. ! CHABELLEY (La(wya ( o ASAITA SOUTHWEST discharging. 4 livestock vessels are at anchorage Caddo (! Zeylac Bossaso CANDALA waiting for livestock readiness. Container vessels get (! 24 Djiboutio Laasqoray Bati ! ALI-SABIEH ! priority berthing, unless the port is extremely congested. ho Dese(! (! ! BOSSASO o DIKHIL o Aasha Caddo BOSSASO COMBOLCHA Xiis ! 48 Kala-Beyr ! o ERIGAVO Lughaye !Badhan 3 Djibouti! Port 18 ! Kemise 106 Geerisa ( 6 ! 120 The bulk terminal remains congested. Currently, 4 vessels with ! Ceerigaabo (!o Ceel-Doofaar 12 BERBERA 85 Haafuun bulk cargo are at berth, while 4 others are at anchorage, waiting ! Laso-Dawaco Ciisse 178 Berbera (! 24 5 ! ! o h to berth. More bulk cargo vessels are expected this week. Harirad ! (! ! Baki o (! Shunting challenges continue as most available trucks are being ! BERBERA Xagal (! Boon ( ! ! o SCUSCIUBAN used at the bulk terminal. ! ! 36 ! 72 Iskushuban Gewane Kidiyood 60 ! Laas Ciidle Buraan ! 1 Boorama Alhamdulilah Xiriiro 108 10°N ! (! ! (! Ceel Afweyn ! 10°N BOORAMAo( Darasalaam Sheikh 11 Huluul Beeyada! 2 1 Rako Xin-Galool Dhahar Guud Cad ! (! Gebiley Darar Weyne 156 ! ! A.T.D. YILMA INTL Sheekha ! ! 9 (! Debre Birhan ! (! ! 12 o! Garbo Haadley ! 75 64 Awr-Boogays GARDO ((! Dire Dawa Kalabaydh 2 ! 8 (! Burco BURAO Gar Adag ! JIJIGA Odweyne (!o ! Baraagaha (!o (! Bandarbayla Hargeisa (o! 2 159 Qardho o Allay baday! HARGEISA (! Qol (! ! Sayla Bari 12 (! K’ebri 12! 12 6 Gumb!uraha Ina Taleex Harar Ji Jiga Balli-Cabane ! 14 ! Qool-Caday Afmadoobe ! (! ! o ( ! 12 ! (! HargAweiassah Airport Gumar ! ! Salahley 123 4 Caynabo Gowsa Weyne Xudun (! !. -

LAND MINES in NORTHERN SOMALIA a Report by Physicians

HIDDEN ENEMtES LAND MINES IN NORTHERN SOMALIA A Report by Physicians for Human Rights November 1992 CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I. INTRODUCTION Hidden Enemies 11. BACKGROUND AND HISTORY OF MINE WARFARE Land Mines in international Law The Basic Rule: Protecting Civilians and Civilian Objects Recording Requirement Use of Plastic Mines 111. THE AFTERMATH OF WAR Historical Background Northern Somalia Today IV. THE MINES AND THEIR CONSEQUENCES The Tnjured Health Care in Somaliland Acutc Care Rehabilitation V. MINE ERAD[CATION hfine Awareness Resettlement VI. OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS Coordination of Planning and Operations Mine Survey and Eradication Mine Awareness Program Acute Care Facilities and Surgical Training Rehabilitation Services APPENIIIX A: Land Mine Situation in Somaliland, Prepared by the Somali Relief and Rehabilitation Association, 1992 APllENDIX B: Land h11nes: Questionnaire for Patients w-ith hli nc Injuries APPENDlX C: Land Mines: Questionnaire for Health Professionals RlRLltICj RAPHY GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS HI Handicap international ICRC International Cornmittec of the Red Cross IED Improvised Explosive Device MSF Mkdecins Sans Frontikres Doctors without Borders SNM Somal I National Movement SOMRA Somali Relief Agency SORRA Somali Relief and Rehabilitation Association UNDP United Nations Developrr~ent Programme UNHCR United Nations High Commissir?ner for Refugees UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Dr. Jonathan Fine, a senior ~ncdicalconwltant and former executive director of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR), based on research undertdkun ir~ norther11 Somalia (Somaliland) between February 16 and March 2, 1992. Dr. Fine uds accompanied on the trip by Dr. Chris Giannou, a Canahan surgeon with over a dccadt. or cxperiznce with vjctirns of war trauma.