Queen's Marsh Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Totnes to Littlehempston Feasibility Report

Totnes to Littlehempston Proposed Cycle Route Feasibility Study Route Analysis (Refers to the Route Options Described in Totnes to Littlehempston Proposed Cycle Route Comparison of Possible Alternative Options November 2011) Devon County Council February 2012 1 Introduction The purpose of this report is to expand on the preliminary study of possible alternative options for a cycle route from Totnes to Littlehempston. Option 1 Bridgetown Hill and Bourton Lane Description The route starts on the A385 which is the main route between Totnes and Torbay before turning onto Bourton Lane which starts as a well surfaced housing estate road, becomes a country lane then deteriorates into a rough track with potholes, streams cut by water erosion, concrete patched areas and rough bedrock. In some places the track surface is the underlying bedrock. At present a 4wd, quad bike, mountain bike or light walking boots are required to negotiate the route Gradients are long and steep with little respite from climbing. Width south of the crest are 3m plus some verge space for passing North of the crest width is 2.5m tight between hedges with passing only possible in gateways. The route crosses the busy A381 where the speed limit is 60mph and visibility is severely substandard when looking right when travelling northwards. Works required. A new path would require construction from Lower Bourton to Combe Cottage. To the south of the highest point considerable existing erosion indicates that drainage is a problem and a sealed path would be required for longevity. The path would be shared with agricultural traffic and will therefore need to be constructed at an appropriate standard for this. -

MS2 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

MS2 bus time schedule & line map MS2 Kingsbridge - The Willows View In Website Mode The MS2 bus line (Kingsbridge - The Willows) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Kingsbridge: 1:10 PM (2) The Willows: 9:45 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest MS2 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next MS2 bus arriving. Direction: Kingsbridge MS2 bus Time Schedule 41 stops Kingsbridge Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Marks & Spencer, the Willows Browns Bridge Road, Torquay Tuesday Not Operational Nicholson Road, the Willows Wednesday 1:10 PM Browns Bridge, the Willows Thursday Not Operational Riviera Way, England Friday Not Operational Coventry Farm, Kingskerswell Saturday Not Operational Manor Gardens, Kingskerswell Arch, Kingskerswell Water Lane, Kingskerswell MS2 bus Info Direction: Kingsbridge Jurys Corner, Kingskerswell Stops: 41 Trip Duration: 80 min Lyndhurst Avenue, Kingskerswell Line Summary: Marks & Spencer, the Willows, Nicholson Road, the Willows, Browns Bridge, the Caravan Park, Kingskerswell Willows, Coventry Farm, Kingskerswell, Manor Gardens, Kingskerswell, Arch, Kingskerswell, Jurys Penn Inn, Milber Corner, Kingskerswell, Lyndhurst Avenue, Kingskerswell, Caravan Park, Kingskerswell, Penn A381, Newton Abbot Inn, Milber, Linden Terrace, Newton Abbot, Bradley Linden Terrace, Newton Abbot Road, Newton Abbot, Ogwell Cross, East Ogwell, Turn, Abbotskerswell, Abbotshill Park, Bradley Road, Newton Abbot Abbotskerswell, Two Mile Oak Inn, Abbotskerswell, -

Planning Appeals Update PDF 70 KB

South Hams District Council DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 11-Mar-20 Appeals Update from 31-Jan-20 to 27-Feb-20 Ward Allington and Strete APPLICATION NUMBER : 0869/19/FUL APP/K1128/W/19/3235270 APPELLANT NAME: Mr C Grigg PROPOSAL : Associated operational development to allow for conversion of stone barn to flexible use (cafe) as consented under prior approval 0189/19/PAU, including change of use of land to provide extended curtilage for associated access, parking, turning and landscaping LOCATION : Old Stone Barn With Land At Sx778426 Frogmore APPEAL STATUS : Appeal decided APPEAL START DATE: 15-October-2019 APPEAL DECISION: Dismissed (Refusal) APPEAL DECISION DATE: 07-February-2020 Ward Dartmouth and Kingswear APPLICATION NUMBER : 2731/19/VAR APP/K1128/W/20/3245718 APPELLANT NAME: Mr Mike Griffiths PROPOSAL : Variation of condition 2 (approved plans) of planning consent 2191/18/FUL for proposed garage and driveway extension LOCATION : Moonraker The Keep Gardens Dartmouth Devon TQ6 9JA APPEAL STATUS : Appeal Lodged APPEAL START DATE: 17-February-2020 APPEAL DECISION: APPEAL DECISION DATE: Ward Loddiswell and Aveton Gifford APPLICATION NUMBER : 1383/19/FUL APP/K1128/W/19/3235854 APPELLANT NAME: Mrs E Perraton PROPOSAL : Associated operational development to allow for change of use of building to flexible use (C1), following 0565/18/PAU (resubmission of consent 0271/19/FUL) LOCATION : Redundant Barn Gratton Farm Loddiswell Devon TQ7 4DA APPEAL STATUS : Appeal decided APPEAL START DATE: 15-October-2019 APPEAL DECISION: Dismissed (Refusal) -

Twentieth Century War Memorials in Devon

386 The Materiality of Remembrance: Twentieth Century War Memorials in Devon Volume Two of Two Samuel Walls Submitted by Samuel Hedley Walls, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Research in Archaeology, April 2010. This dissertation is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signed.................................................................. Samuel Walls 387 APPENDIX 1: POPULATION FIGURES IN STUDY AREAS These tables are based upon figures compiled by Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2009), Hoskins (1964), Devon Library and Information Services (2005). EAST DEVON Parish Coastline Train Notes on Boundary Changes 1891 1901 1911 1921 1931 1951 Station Awliscombe 497 464 419 413 424 441 Axminster 1860 – 2809 2933 3009 2868 3320 4163 Present Axmouth Yes Part of the parish transferred in 1939 to the newly combined 615 643 595 594 641 476 Combpyne Rousdon Parish. Aylesbeare The dramatic drop in population is because in 1898 the Newton 786 225 296 310 307 369 Poppleford Parish was created out of the parish. Beer Yes 1046 1118 1125 1257 1266 1389 Beer was until 1894 part of Seaton. Branscombe Yes 742 627 606 588 538 670 Broadclyst 1860 – 2003 1900 1904 1859 1904 2057 1966 Broadhembury 601 554 611 480 586 608 Buckerell 243 240 214 207 224 218 Chardstock This parish was transferred to Devon from Dorset in 1896. -

Village Lives

1 Cover: Ralph Hoare of Mount Barton returns home, C. 1940 Back cover: Vera White and Ruby Manning washing their hair at Higher Lake Farm, late 1920s 2 Village Lives in Woodland, Broadhempston, Staverton, Landscove and Littlehempston Published by Parish News Editors 3 Contents Introduction Agriculture The Church Housing Village People Natural History The School The Shop War Time Ramblings and Curiosities Controversies Water Women’s Institute Acknowledgements 4 Sara Coish helping out the Mannings and the Webbers 5 Introduction The Editors of the Parish News were keen at Broadhempston and Woodland. In 1981 the to preserve and publicise some of the interesting parishioners of Littlehempston Church joined articles published over many years. These chosen the Parish News, followed in 1987 by Staverton items within give a wide and wonderful picture of and Landscove – the five combined parishes as village life, it’s people and society, it’s changes and represented in our magazine today. Since 1990 the even it’s controversies. They were published in the church has relinquished it’s role in the Parish News Parish News between 1975 and 2009, presenting production and it has been edited and presented a rich and varied picture of life in our five villages. by a group of interested parishioners. Among memories of wartime, for instance, are the Home Guard in an old chicken house on the Beacon, looking out for enemy aircraft; a young evacuee having to learn “manners” and eat in the kitchen before being allowed to join the family for meals, and the Women’s Institute receiving food parcels from Australia. -

Display PDF in Separate

local environment agency plan RIVER TEIGN CONSULTATION REPORT MARCH 1997 The River Teign Local Environment Agency Plan (LEAP) aims to promote integrated environmental management of this important area of Devon. It seeks to develop partnerships with a wide range of organisations and individuals who have a role to play in the management of the River Teign and Torbay Streams. This plan embodies the Agency’s commitment to realise improvements to the environment. An important stage in the production of the plans is a period of public consultation. This Consultation Report is being circulated widely both within and outside of the catchment and we are keen to draw on the expertise and interests of the local communities involved. Please comment - your views are important, even if it is to say that you think particular issues are necessary or that you support the plan and its objectives. Following on from the Consultation Report an Action Plan will be produced with an agreed programme for the future protection and enhancement of this much loved area. We will use these Plans to ensure that improvements in the local environment are achieved and that good progress is made towards the vision. VAA-£.r>------- GEOFF BATEMAN Area Manager (Devon) Environment -Au^ncy Information Centre Your Views We hope that this report will be read by everyone who has an interest in the environment of the River Teign Catchment. Your views will help us finalise the Action Plan. Have we identified all the problems in the catchment? If not, we would like to know. Are there any issues which you would like to highlight? Please fill in the questionnaire provided and send your comments by 31st May 1997 to: Richard Parker Environment Planner - Devon Area Manley House , Kestrel Way EXETER Devon EX2 7LQ We will not republish this Consultation Report. -

Notice of Election Double Column

NOTICE OF ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish/Town Councillors for the Parishes/Towns listed below Parishes/Towns Number of Parish/Town Parishes/Towns Number of Parish/Town Councillors to be elected Councillors to be elected Ashprington Seven Kingsbridge (Kingsbridge Three Westville) Aveton Gifford Nine Kingston Seven Berry Pomeroy (Bridgetown) Four Kingswear (Hillhead) Five Berry Pomeroy (Village) Three Kingswear (Kingswear) Five Bickleigh (Bickleigh) Two Littlehempston Five Bickleigh (Woolwell) Seven Loddiswell Ten Bigbury Seven Malborough Nine Blackawton Seven Marldon Ten Brixton Nine Modbury Twelve Buckfastleigh West Seven Newton & Noss Twelve Buckland-Tout-Saints Five North Huish Seven Charleton Eight Rattery Seven Chivelstone Seven Ringmore Seven Churchstow Seven Salcombe Twelve Cornwood Eleven Shaugh Prior Nine Cornworthy Seven Slapton Nine Dartington Eleven South Brent (Brentmoor) Three Dartmouth (Dartmouth Clifton) Ten South Brent (Village) Nine Dartmouth (Dartmouth Six South Huish Seven Townstal) Dean Prior Five South Milton Seven Diptford Eight South Pool Seven Dittisham Nine Sparkwell Eleven East Allington Seven Staverton Nine East Portlemouth Seven Stoke Fleming Nine Ermington Ten Stoke Gabriel Nine Frogmore & Sherford Five Stokenham Thirteen (Frogmore) Frogmore & Sherford (Sherford) Three Strete Seven Halwell & Moreleigh Ten Thurlestone Seven Harberton (Harberton) Six Totnes (Totnes Bridgetown) Six Harberton (Harbertonford) Six Totnes (Totnes Town) Ten Holbeton Ten Ugborough (Ugborough East) Ten Holne -

Totnes to Littlehempston

Totnes to Littlehempston Proposed Cycle Route Comparison of Possible Alternative Options November 2011 Introduction The purpose of this report is to summarise the results of a preliminary study of possible alternative options for a cycle route from Totnes to Littlehempston. Background The County Council’s Strategic Cycle Network envisages a long distance cycle route from Axminster to Plymouth, forming part of the NCN2 south coast national cycle route. The section of the NCN2 on the western side of the Exe Estuary from Exeter to Dawlish (part of the Exe Estuary Trail) is expected to be completed by 2013, and investigatory work is currently in progress for the continuation of this route along the northern side of the Teign Estuary from Teignmouth to Newton Abbot. A preferred alignment for the continuation of the NCN2 route from Newton Abbot to Totnes has yet to be agreed, and no funding to construct such a scheme has been identified, but a possible primarily on-road route has been considered via Denbury, Broadhempston and Staverton. In Totnes, the existing cycling infrastructure is located primarily to the south of the river, with a mainly traffic-free shared use path to Dartington and on to Huxhams Cross, where the NCN2 signed route continues to South Brent, Ivybridge and Plymouth. Two main options therefore exist for linking Totnes to the NCN2 – either via Dartington to Huxhams Cross, or alternatively via Littlehempston to Staverton. It is possible that a case could be made for both these routes in order to optimise the use of the cycle network for local journeys. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document For

Phil Norrey Chief Executive To: The Chair and Members of the County Hall South Hams Highways and Topsham Road Traffic Orders Committee Exeter Devon EX2 4QD (See below) Your ref : Date : 28 June 2018 Email: [email protected] Our ref : Please ask for : Fiona Rutley 01392 382305 SOUTH HAMS HIGHWAYS AND TRAFFIC ORDERS COMMITTEE Friday, 6th July, 2018 A meeting of the South Hams Highways and Traffic Orders Committee is to be held on the above date at 10.30 am at Follaton House, Plymouth Road to consider the following matters. P NORREY Chief Executive A G E N D A PART 1 - OPEN COMMITTEE 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Election of Chair (NB: In accordance with the County Council’s Constitution, the Chair and Vice-Chair must be County Councillors. County and District Councillors may vote) 3 Election of Vice-Chair (NB: In accordance with the County Council’s Constitution, the Chair and Vice-Chair must be County Councillors. County and District Councillors may vote) 4 Minutes (Pages 1 - 4) Minutes of the meeting held on 20 April 2018 attached. 5 Items Requiring Urgent Attention Items which in the opinion of the Chairman should be considered at the meeting as matters of urgency. MATTERS FOR DECISION 6 Annual Local Waiting Restriction Programme (Pages 5 - 32) Report of the Chief Officer for Highways, Infrastructure Development and Waste (HIW/18/50) attached. Electoral Divisions: All in South Hams 7 Item under SO23(2) - Parking Permits In accordance with Standing Order 23(2) Councillor Brazil has requested that the Committee consider this matter, ie:- (a) Exemptions for Carers (b) Use by builders etc. -

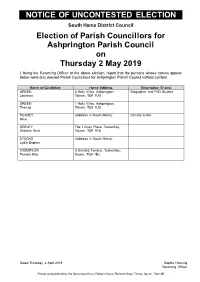

Notice of Uncontested Election Results 2019

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Ashprington Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) GREEN 8 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Biographer and PhD Student Laurence Totnes, TQ9 7UU GREEN 1 Holly Villas, Ashprington, Thomas Totnes, TQ9 7UU PEAREY (Address in South Hams) Climate Crisis Mike SEELEY Flat 1 Quay Place, Tuckenhay, Sheelah Ruth Totnes, TQ9 7EQ STOCKS (Address in South Hams) Lydia Daphne THOMPSON 9 Orchard Terrace, Tuckenhay, Pamela May Devon, TQ9 7EJ Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Sophie Hosking Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Follaton House, Plymouth Road, Totnes, Devon, TQ9 5NE NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION South Hams District Council Election of Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council on Thursday 2 May 2019 I, being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Aveton Gifford Parish Council without contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BROUSSON 5 Avon Valley Cottages, Aveton Ros Gifford, TQ7 4LE CHERRY 46 Icy Park, Aveton Gifford, Sue Kingsbridge, Devon, TQ7 4LQ DAVIS-BERRY Homefield, Aveton Gifford, TQ7 David Miles 4LF HARCUS Rock Hill House, Fore Street, Sarah Jane Aveton Gifford, -

Devon County Map (CG)

A B C D E F G To Bristol H 300 .309 309.310 310 .EC Lynmouth Countisbury A LYNTON 21 .21 . 31 .33 EC 35.300 .301 300 301 Barbrook Highbridge ILFRACOMBE 33 33 300 310 Porlock 35 33 301 309 EC Lee 35 21 Berrynarbor 300 EC A Combe 300 1 31 21 33 Parracombe 1 Mortehoe 303Mullacott Cross 31 Martin 300 MINEHEAD 31 .303 301 309 310 31 303 309 300 EC 31 .303 Woolacombe 301 300 31 309 Blackmoor Gate 303 303 West 309 EXMOOR Down 303 310 21. 21C 303 Arlington ver 21 Georgeham Ri Exe 21C 21 Croyde Bay 21. 21C A 21 309 Croyde 303 Guineaford Muddiford 21 C Knowle Bridge Bridgwater 21 Shirwell Saunton Bratton 310 Fleming BARNSTAPLE 303 301 Braunton 309 Chelfham terminating: 21 21 Barton 873 A Ashford 303 657 657 5B. 9 .15A .15C . 21C .71 21 Brayford 21C 72.75B.85.118 . 155 .301.303 303 Goodleigh 310 654 7 309.310.319.322 .325.372 Chivenor 654.65 386.646.654.657.658 BARNSTAPLE 657 873 calling: Fremington (see left for details) 155 21 . 21A 658 657 Yelland 21A Bickington Landkey East 21 Barnstaple West Buckland SOMERSET A Buckland 21 5B 5B 71.72.322 Bishop’s Appledore 15A Tawstock Tawton 2 9 658 ay 2 16. 21 Instow 15C 155 155 r B North 75B.85 71 873 16.21A r 21 Westward Ho! Swimbridge e Molton v 25.398 118 72 658 i 16 R 155 155 Molland 16 Northam 319 155 Dulverton Wiveliscombe 21 322 155 657 856 372 696 Cotford St. -

XXXXX Pigwhistle Festive WEB.Indd

Merry Christmas from all the team at the Newton Road, Littlehempston, Totnes, Devon TQ9 6LT Newton Road, Littlehempston, Totnes, Devon TQ9 6LT Tel: 01803 863733 Email: [email protected] Tel: 01803 863733 Email: [email protected] www.thepigandwhistleinn.co.uk www.thepigandwhistleinn.co.uk THE PIG & WHISTLE THE PIG & WHISTLE Christmas Bistro Menu Christmas Day Menu STARTERS STARTERS Roasted Parsnip & Apple Soup Roasted Parsnip Brixham Crab Bon Bons & Apple Soup Panko breadcrumbed, mixed Served with crusty sourdough bread Crouton & crusty sourdough bread leaf, lemon & chive aioli Creamy Garlic & Pancetta Mushrooms Beetroot & Goats Game Terrine Sautéed in garlic, cream, dijon mustard & white wine, Cheese Stack Berry Pomeroy pheasant, Dartmoor topped with parmesan, served with crusty sourdough bread (Tofu & Halloumi for Vegan option) wild venison, Westcountry duck, crusty Goats cheese & chives layered sourdough bread and fig compote Smoked Salmon & Prawn Bon Bons with beetroot, balsamic glaze, Cantaloupe Melon & Parma Ham Bound in creamy mash potato & panko breadcrumb, zesty lemon mayo micro herb leaves Raspberry vinaigrette Baked Goats Cheese & Beetroot Salad MAIN COURSE With a balsamic glaze & roasted walnuts Traditional Roast Turkey Yorkshire pudding, pig in blanket, cranberry pork & chestnut stuffing, gravy MAIN COURSE Slow Roasted Lamb Shank Traditional Roast Turkey Sticky red wine, redcurrant & rosemary jus, dauphinois potatoes Vegan Butternut, Spinach & Wild Mushroom Wellington Yorkshire pudding, pig in blanket, cranberry pork & chestnut stuffing, With vegan gravy roasted carrots, parsnip, potatoes & sautéed brussel sprouts Dartmoor Wild Venison Steak Tuscan Salmon Pan fried with wild mushroom cream sauce Fillet of Scottish salmon with a potato & herb rosti Each of the above served with roasted potatoes (unless otherwise stated) and seasonal vegetables.