The Police in Colonial Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resettlement of the Karen in Minnesota A

THE RESETTLEMENT OF THE KAREN IN MINNESOTA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOLOF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Kathleen J Lytle IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Hollister, Adviser January, 2015 Kathleen J Lytle 2015 Copyright This thesis is dedicated to: My husband Allen, who walked with me on this journey; My mom Helen, who has always been the most inspiring role model; My children Kari, Jeff, and Laurie; And the Karen people of Minnesota i Abstract Minnesota has a long history of welcoming immigrants and refugees into its communities. Following the Vietnam War large numbers of Southeast Asian (SEA) refugees came to Minnesota. With the implementation of the Refugee Act of 1980, a formal refugee resettlement program was created nation-wide. As part of the Refugee Act of 1980 Voluntary agencies (VOLAGs), were established to help the refugees with their resettlement process. Soon after the arrival of refugees from Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, refugees from other countries began coming to Minnesota. In the 1990s refugees from the former Soviet Union began resettling in Minnesota. In the mid 1990s refugees from East Africa began arriving. In the early 2000s, large numbers of Karen refugees from Burma began coming to Minnesota. In order to help the Karen refugees in their acculturation, it is important for the community within which they are living to understand them and their culture. Using an ethnographic approach, this qualitative research project is aimed at understanding the lived experiences of the Karen and their resettlement. -

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare Title and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue>State Formation in Comparative Perspectives) Author(s) Callahan, Mary P. Citation 東南アジア研究 (2002), 39(4): 513-536 Issue Date 2002-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/53713 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. -

The Role of Indian Diaspora in India- Myanmar Relations

The Role of Indian Diaspora in India- Myanmar Relations Dissertation submitted to the Department of International Relations, Sikkim University in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Submitted by Sarita Rai < DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737 102 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE NUMBER Declaration Certificate Acknowledgements-------------------------------------------------------I Abbreviations-------------------------------------------------------------II CHAPTER-I--------------------------------------------------------------1-28 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER-II-------------------------------------------------------------29-56 DIASPORA AND FOREIGN POLICY: A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK CHAPTER-III-----------------------------------------------------------57-77 INDIA-MYANMAR BILATERAL RELATIONS POST 1994 CHAPTER-IV----------------------------------------------------------78-101 EXPLORING INDIAN DIASPORA IN INDIA-MYANMAR RELATIONS CHAPTER-V-----------------------------------------------------------102-106 CONCLUSION REFERENCES---------------------------------------------------------107-116 APPENDICES----------------------------------------------------------I-XI 28. 2. 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the dissertation entitled “The Role of Indian Diaspora in India- Myanmar Relations” submitted by me for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy to Sikkim University is my own work. The thesis has not been submitted for any other degree -

Protection of Lives and Dignity of Women Report on Violence Against Women in India

Protection of lives and dignity of women Report on violence against women in India Human Rights Now May 2010 Human Rights Now (HRN) is an international human rights NGO based in Tokyo with over 700 members of lawyers and academics. HRN dedicates to protection and promotion of human rights of people worldwide. [email protected] Marukou Bldg. 3F, 1-20-6, Higashi-Ueno Taitou-ku, Tokyo 110-0015 Japan Phone: +81-3-3835-2110 Fax: +81-3-3834-2406 Report on violence against women in India TABLE OF CONTENTS Ⅰ: Summary 1: Purpose of the research mission 2: Research activities 3: Findings and Recommendations Ⅱ: Overview of India and the Status of Women 1: The nation of ―diversity‖ 2: Women and Development in India Ⅲ: Overview of violence and violation of human rights against women in India 1: Forms of violence and violation of human rights 2: Data on violence against women Ⅳ: Realities of violence against women in India and transition in the legal system 1: Reality of violence against women in India 2: Violence related to dowry death 3: Domestic Violence (DV) 4: Sati 5: Female infanticides and foeticide 6: Child marriage 7: Sexual violence 8: Other extreme forms of violence 9: Correlations Ⅴ: Realities of Domestic Violence (DV) and the implementation of the DV Act 1: Campaign to enact DV act to rescue, not to prosecute 2: Content of DV Act, 2005 3: The significance of the DV Act and its characteristics 4: The problem related to the implementation 5: Impunity of DV claim 6: Summary Ⅵ: Activities of the government, NGOs and international organizations -

Assemblée Générale GÉNÉRALE A/HRC/11/2/Add.2 23 Mars 2009

NATIONS UNIES A Distr. Assemblée générale GÉNÉRALE A/HRC/11/2/Add.2 23 mars 2009 FRANÇAIS Original: ANGLAIS CONSEIL DES DROITS DE L’HOMME Onzième session Point 3 de l’ordre du jour PROMOTION ET PROTECTION DE TOUS LES DROITS DE L’HOMME, CIVILS, POLITIQUES, ÉCONOMIQUES, SOCIAUX ET CULTURELS, Y COMPRIS LE DROIT AU DÉVELOPPEMENT Rapport du Rapporteur spécial sur les exécutions extrajudiciaires, sommaires et arbitraires M. Philip Alston Additif MISSION AU BRÉSIL* * Le résumé du présent rapport est distribué dans toutes les langues officielles. Le rapport proprement dit est joint en annexe au résumé, et il est distribué dans la langue originale seulement. GE.09-12623 (F) 030409 060409 A/HRC/11/2/Add.2 page 2 Résumé Le Brésil a l’un des taux d’homicide les plus élevés au monde, avec plus de 48 000 morts chaque année. Les meurtres commis par des gangs, des détenus, des policiers, des escadrons de la mort et des tueurs à gage font régulièrement les gros titres de la presse nationale et internationale. Une grande partie de la population, effrayée par le taux de criminalité élevé et convaincue que le système de justice pénale est trop lent pour poursuivre les criminels, est favorable aux exécutions extrajudiciaires et à la justice privée. De nombreuses personnalités politiques, désireuses de gagner les faveurs d’un électorat apeuré, ne font pas montre de la volonté politique nécessaire pour faire diminuer le nombre d’exécutions commises par des policiers. Ce comportement doit changer. Les États ont l’obligation de protéger leurs citoyens en prévenant et en réprimant la criminalité. -

Development Ofmonitoring Instruments Forjudicial and Law

Background Research on Systems and Context on Systems Research Background Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement institutions in the Western Balkans Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans 2009 - 2011 CARDS Regional Action Programme With funding by the European Commission April 2010 Disclaimers This Report has not been formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Comments on this report are welcome and can be sent to: Statistics and Survey Section United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 5475 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 7 5475 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org 1 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context 2 Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement Institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Background Research on Systems and Context Justice and Home Affairs Statistics in the Western Balkans April 2010 3 Acknowledgements Funding for this report was provided by the European Commission under the CARDS 2006 Regional Action Programme. This report was produced under the responsibility of Statistics and Surveys Section (SASS) and Regional Programme Office for South Eastern Europe (RPOSEE) of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) based on research conducted by the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). -

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma*

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. Administra- tive simplifications along territorial and racial lines resulted in political, economic, and social boundaries that continue to divide the country today. Bureaucratic and security mech- anisms politicized violence along territorial and racial lines, creating “two Burmas” in the administrative and security arms of the state. Despite the “laissez-faire” proclamations of colonial state officials in Burma, this geographically and functionally limited state nonethe- less established durable administrative structures that precluded any significant integration throughout the territory for a century to come. -

Central Banking at the Periphery of the British

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the author’s version of an article from the following conference: Turnell, Sean (2007) The Elastic margin : central banking theory and practice in colonial Burma. Regarding the past : History of Economic Thought Society of Australia Conference (20th : 10 - 12 July 2007 : Brisbane). Access to the published version: http://www.uq.edu.au/economics/hetsa/HETSA%2020071%20Turnell.pdf The Elastic Margin: Central Banking Theory and Practice in Colonial Burma by Sean Turnell Macquarie University [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this paper is to bring to light efforts to fashion a central bank in Burma during the years in which the country was a province of British India. Throughout this era, which lasted from 1886 to 1937, questions of money and finance were chiefly the preserve of the Raj in Calcutta. Behind the scenes, however, plans to establish a central bank for Burma itself were promoted by imperial officials well-schooled in the great monetary and banking controversies of the age. These plans borrowed ideas from many likely and unlikely places but they were also innovative in their own right, and were not without useful insights for central banks everywhere. Lastly, this advocacy for a central bank in Burma was also indicative of a political economy discourse in the country that was more vigorous, and theoretically sophisticated, than is commonly supposed. JEL Classification: N25, E42, E58. Keywords: Monetary institutions, British Empire, Burma, Indian monetary reform. 1 I Introduction For most of the history of colonial Burma all the important questions of money and finance were decided upon in India. -

Statelessness in Myanmar

Statelessness in Myanmar Country Position Paper May 2019 Country Position Paper: Statelessness in Myanmar CONTENTS Summary of main issues ..................................................................................................................... 3 Relevant population data ................................................................................................................... 4 Rohingya population data .................................................................................................................. 4 Myanmar’s Citizenship law ................................................................................................................. 5 Racial Discrimination ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arbitrary deprivation of nationality ....................................................................................................... 7 The revocation of citizenship.................................................................................................................. 7 Failure to prevent childhood statelessness.......................................................................................... 7 Lack of naturalisation provisions ........................................................................................................... 8 Civil registration and documentation practices .............................................................................. 8 Lack of Access and Barriers -

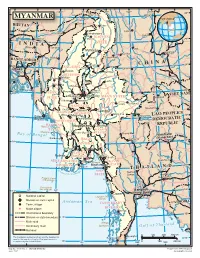

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations.