Concourse Dreams: a Bronx Neighborhood and Its Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

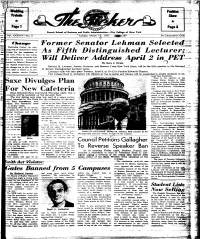

Former Senator Lehman As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu Will Deliver

:iVn-1,,TSW«a^ .-•tfinrf.V. .,+,. •"- • , --v Show ' • • V '•<•'' •• — * Page 3 '•"•:• ^U- Baruch School of Business and Public Administration City College of New York Vol: XXXVri!—No. 8 Tuesday. March 19. 1957 389 By Subscription -Only Former Senator Lehman Beginning Friday, the cafe- [tgria will be clooed at 3 evei> Friday- for the remainder of As Fifth, Distinguished Lectu [the term. Prior to this ruling, the cafeteria was closed &t 4:30. [The Cafeteria Committee, Will Deliver Address April 2 in [headed by Ed-ward Mamraen of By Gary J. Strum . -i| the Speech Department, made O the change due to lack of busi Herbert H. Lehman, former Governor and Senator f rom New York State, will be the fifth speaker in the Bernard ness after 3. There is no eve- M. Baruch Distinguished Lecturer series. " * " I ning session service Fridays. Lehman's talk will take place Tuesday, April 2, at 10:15 in Pauline Edwards Theatre. .•...•---. " ; / City College Buell G. Gallagher will officiate at the occasion and classes will be suspended to enable students to'afc- : tend the function. Prior to his election to the United States Senate in 1949, axe Divulges Plan Lehman worked as Director Gen-, eral of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administra tion. or New Cafeteria Lehman was born in New York Dean Emanuel Saxe announced Thursday night that a City March 28, 1878, and he re afeteria will be installed on the eleventh floor. ceived a BA degree from Wil The new dining area plan was part of a space survey liams College. -

The City Record. Borough of the Bronx. •

THE CITY RECORD. VoL. XXXIII. NEW YORK, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 1905. NUMBER 9843. Estimated THE CITY RECORD. No. Hearing. Cost. Initiated. OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK. 332. East One Hundred and Seventy-second street, from Published Under Authority of Section 1526, Greater New York Charter, by the Boston road to Southern Boulevard Mar. 2 Mar. 2 336.- Bronx street, from Tremont avenue to One Hundred BOARD OF CITY RECORD. and Eightieth street Mar. 2 Mar. 2 GEORGE B. McCLELLAN, MAYOR. 347. Locust avenue, from White Plains road to Elm street. Mar. I I Mar. r s 358. Twenty-first avenue, from Second street to Bronxwood JOHN J. DELANY, CORPORATION COUNSEL. EDWARD M. GROUT, COMPTROLLER. avenue Mar. 27 359. Twentieth avenue, from Bronx river to Kingsbridge road Mar. 27 PATRICK J. TRACY, SUPERVISOR. 36o. Byron street, from Two Hundred and Thirty-third street Published daily, except legal holidays. to Baker avenue Mar. 27 Subscription, $9.3o per year, exclusive of supplements. Three cents a copy. 362. Concord street, from Two Hundred and Thirty-third street to Baker avenue MRS. 27 SUPPLEMENTS: Civil List (containing names, salaries, etc., of the city employees), 25 cents; 363. Twenty-second avenue, from Bronx river to Fourth Canvass, to cents; Registry Lists, 5 cents each assembly district; Law Department and Finance street. Filed. New petition presented Mar. 27 Department supplements, io cents each; Annual Assessed Valuation of Real Estate, 25 cents each 352. Jennings street, from Edgewater road to Bronx river Mar. 27 section. 365. Belmont street, between Longwood avenue and Feather Published at Room z, City Hall (north side), New York City. -

Internet Killed the B-Boy Star: a Study of B-Boying Through the Lens Of

Internet Killed the B-boy Star: A Study of B-boying Through the Lens of Contemporary Media Dehui Kong Senior Seminar in Dance Fall 2010 Thesis director: Professor L. Garafola © Dehui Kong 1 B-Boy Infinitives To suck until our lips turned blue the last drops of cool juice from a crumpled cup sopped with spit the first Italian Ice of summer To chase popsicle stick skiffs along the curb skimming stormwater from Woodbridge Ave to Old Post Road To be To B-boy To be boys who snuck into a garden to pluck a baseball from mud and shit To hop that old man's fence before he bust through his front door with a lame-bull limp charge and a fist the size of half a spade To be To B-boy To lace shell-toe Adidas To say Word to Kurtis Blow To laugh the afternoons someone's mama was so black when she stepped out the car B-boy… that’s what it is, that’s why when the public the oil light went on changed it to ‘break-dancing’ they were just giving a To count hairs sprouting professional name to it, but b-boy was the original name for it and whoever wants to keep it real would around our cocks To touch 1 ourselves To pick the half-smoked keep calling it b-boy. True Blues from my father's ash tray and cough the gray grit - JoJo, from Rock Steady Crew into my hands To run my tongue along the lips of a girl with crooked teeth To be To B-boy To be boys for the ten days an 8-foot gash of cardboard lasts after we dragged that cardboard seven blocks then slapped it on the cracked blacktop To spin on our hands and backs To bruise elbows wrists and hips To Bronx-Twist Jersey version beside the mid-day traffic To swipe To pop To lock freeze and drop dimes on the hot pavement – even if the girls stopped watching and the street lamps lit buzzed all night we danced like that and no one called us home - Patrick Rosal 1 The Freshest Kids , prod. -

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

Southwest Bronx (SWBX): a Map Is Attached, Noting Recent Development

REDC REGION / MUNICIPALITY: New York City - Borough of Bronx DOWNTOWN NAME: Southwest Bronx (SWBX): A map is attached, noting recent development. The boundaries proposed are as follows: • North: Cross Bronx Expressway • South: East River • East: St Ann’s Avenue into East-Third Avenue • West: Harlem River APPLICANT NAME & TITLE: Regional Plan Association (RPA), Tom Wright, CEO & President. See below for additional contacts. CONTACT EMAILS: Anne Troy, Manager Grants Relations: [email protected] Melissa Kaplan-Macey, Vice President, State Programs, [email protected] Tom Wright, CEO & President: [email protected] REGIONAL PLAN ASSOCIATION - BRIEF BACKGROUND: Regional Plan Association (RPA) was established as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in 1929 and for nearly a century has been a key planner and player in advancing long-range region-wide master plans across the tri-state. Projects over the years include the building of the the Battery Tunnel, Verrazano Bridge, the location of the George Washington Bridge, the Second Avenue subway, the New Amtrak hub at Moynihan Station, and Hudson Yards, and establishing a city planning commission for New York City. In November 2017, RPA published its Fourth Regional Plan for the tri-state area, which included recommendations for supporting and expanding community-centered arts and culture in New York City neighborhoods to leverage existing creative and cultural diversity as a driver of local economic development. The tri-state region is a global leader in creativity. Its world-class art institutions are essential to the region’s identity and vitality, and drive major economic benefits. Yet creativity on the neighborhood level is often overlooked and receives less support. -

Bronx Civic Center

Prepared for New York State BRONX CIVIC CENTER Downtown Revitalization Initiative Downtown Revitalization Initiative New York City Strategic Investment Plan March 2018 BRONX CIVIC CENTER LOCAL PLANNING COMMITTEE Co-Chairs Hon. Ruben Diaz Jr., Bronx Borough President Marlene Cintron, Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation Daniel Barber, NYCHA Citywide Council of Presidents Michael Brady, Third Avenue BID Steven Brown, SoBRO Jessica Clemente, Nos Quedamos Michelle Daniels, The Bronx Rox Dr. David Goméz, Hostos Community College Shantel Jackson, Concourse Village Resident Leader Cedric Loftin, Bronx Community Board 1 Nick Lugo, NYC Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Milton Nuñez, NYC Health + Hospitals/Lincoln Paul Philps, Bronx Community Board 4 Klaudio Rodriguez, Bronx Museum of the Arts Rosalba Rolón, Pregones Theater/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater Pierina Ana Sanchez, Regional Plan Association Dr. Vinton Thompson, Metropolitan College of New York Eileen Torres, BronxWorks Bronx Borough President’s Office Team James Rausse, AICP, Director of Planning and Development Jessica Cruz, Lead Planner Raymond Sanchez, Counsel & Senior Policy Manager (former) Dirk McCall, Director of External Affairs This document was developed by the Bronx Civic Center Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State, NYS Homes and Community Renewal, and Empire State Development. The document was prepared by a Consulting Team led by HR&A Advisors and supported by Beyer Blinder Belle, -

The Bronx Museum of the Arts Is One of the City's More Animated And

THE BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS 1040 GRAND CONCOURSE BRONX NY 10456-3999 T 718 681 6000 F 718 681 6181 WWW.BRONXMUSEUM.ORG About The Bronx Museum of the Arts The Bronx Museum of the Arts is an internationally recognized cultural destination that presents innovative contemporary art exhibitions and education programs and is committed to promoting cross- cultural dialogues for diverse audiences. Since its founding in 1971, the Museum has played a vital role in the Bronx by helping to make art accessible to the entire community and connecting with local schools, artists, teens, and families through its robust education initiatives. In celebration of its 40th anniversary in 2012, the Museum implemented a universal free admission policy, supporting its mission to make arts experiences available to all audiences. The Museum also recently established the Community Advisory Council, a group of local residents that meets monthly and serves as cultural ambassadors for the museum. Located on the Grand Concourse, the Museum’s home is a distinctive contemporary landmark designed by the internationally recognized firm Arquitectonica. Collection The Bronx Museum’s permanent collection demonstrates a commitment to exhibit, preserve, and document the work of artists not typically represented within traditional museum collections. Comprising over 1,000 20th century and contemporary works of art in all media, the collection highlights work by artists of African, Asian, and Latin American ancestry, reflecting the diversity of the borough, as well as by artists for whom the Bronx has been critical to their development. Artists include: Romare Bearden, Willie Cole, Seydou Keïta, Nikki S. Lee, Ana Mendieta, Hélio Oiticica, Jamel Shabazz, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker, as well as Pepón Osorio, Whitfield Lovell, and Xu Bing. -

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

South Bronx Environmental Health and Policy Study, Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis: Final Report

SOUTH BRONX ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND POLICY STUDY Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis Funded with a Congressional Appropriation sponsored by Congressman José E. Serrano and administered through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Planning, Zoning, Land Use, Air Quality and Public Health Final Report for Phase IV December 2007 Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems (ICIS) Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service New York University 295 Lafayette Street New York, NY 10012 (212) 992ICIS (4247) www.nyu.edu/icis Edited by Carlos E. Restrepo and Rae Zimmerman 1 SOUTH BRONX ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH AND POLICY STUDY Public Health and Environmental Policy Analysis Funded with a Congressional Appropriation sponsored by Congressman José E. Serrano and administered through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Planning, Zoning, Land Use, Air Quality and Public Health Final Report for Phase IV December 2007 Edited by Carlos E. Restrepo and Rae Zimmerman Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems (ICIS) Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service New York University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter 1. Introduction 5 Chapter 2. Environmental Planning Frameworks and Decision Tools 9 Chapter 3. Zoning along the Bronx River 29 Chapter 4. Air Quality Monitoring, Spatial Location and Demographic Profiles 42 Chapter 5. Hospital Admissions for Selected Respiratory and Cardiovascular Diseases in Bronx County, New York 46 Chapter 6. Proximity Analysis to Sensitive Receptors using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) 83 Appendix A: Publications and Conferences featuring Phase IV work 98 3 This project is funded through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) by grant number 982152003 to New York University. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Sustainable Communities in the Bronx: Melrose

Morrisania Air Rights Housing Development 104 EXISTING STATIONS: Melrose SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES IN THE BRONX 105 EXISITING STATIONS MELROSE 104 EXISTING STATIONS: Melrose SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES IN THE BRONX 105 MELROSE FILLING IN THE GAPS INTRODUCTIONINTRODUCTION SYNOPSIS HISTORY The Melrose Metro-North Station is located along East 162nd Street between Park and Courtlandt Av- The history of the Melrose area is particularly im- enues at the edge of the Morrisania, Melrose and portant not only because it is representative of the Concourse Village neighborhoods of the Bronx. It is story of the South Bronx, but because it shaped the located approximately midway on the 161st /163rd physical form and features which are Melrose today. Street corridor spanning from Jerome Avenue on the The area surrounding the Melrose station was orig- west and Westchester Avenue on the east. This cor- inally part of the vast Morris family estate. In the ridor was identified in PlaNYC as one of the Bronx’s mid-nineteenth century, the family granted railroad three primary business districts, and contains many access through the estate to the New York and Har- regional attractions and civic amenities including lem Rail Road (the predecessor to the Harlem Line). Yankee Stadium, the Bronx County Courthouse, and In the 1870s, this part of the Bronx was annexed into the Bronx Hall of Justice. A large portion of the sta- New York City, and the Third Avenue Elevated was tion area is located within the Melrose Commons soon extended to the area. Elevated and subway Urban Renewal Area, and has seen tremendous mass transit prompted large population growth in growth and reinvestment in the past decades, with the neighborhood, and soon 5-6 story tenements Courtlandt Corners, Boricua College, Boricua Village replaced one- and two-family homes. -

Listen Up! Trees Along the Grand Concourse Are Ready to Talk

For Immediate Release April 6, 2009 Media Contact: Amanda de Beaufort, Anne Edgar Associates 646 336 7230, [email protected] LISTEN UP! TREES ALONG THE GRAND CONCOURSE ARE READY TO TALK Tree Museum Opens on Sunday, June 21, with a Parade Down Grand Concourse to the Lorelei Fountain Bronx, NY—Along a four-and-a-half-mile stretch of the Grand Concourse—the historic boulevard connecting Manhattan to the parks of the north Bronx—a most unusual “museum without walls” opens Sunday, June 21, 2009, and remains on view 24 hours a day, seven days a week until October 12, 2009 as part of the centennial celebration of the “Park Avenue of the working class.” Conceived and realized by the Irish artist Katie Holten, the Tree Museum invites pedestrians to experience the Bronx in unexpected ways, offering insights into its hardy communities and fragile ecologies. 100 green and flowering trees from 138th Street to Mosholu Parkway, including shade varieties planted a century ago as tiny saplings for the Concourse’s Grand Opening, are the points of entry to this museum. “I’m using the trees as a starting point to look at all the neighborhoods, the environment, and how everything is connected,” says Katie Holten. “I see it as a way to give a voice to the inhabitants, the streets, and neighborhoods from the past, present, and future.” The audio guide at the core of the Tree Museum links the natural and social ecosystems. Markers will identify the trees by species and location number. By keying the location number into a cell phone, a sidewalk “museum-goer” will be able to access audio segments that overlay impressions of the past, present, and future to a walk along the Concourse, whether it be the way that weather affects tree growth or visions of the pre- Concourse Bronx with farmland as far as the eye can see, the glory days of the 1920s, and the rise of Hip Hop in the 1970s.