The Overview Treatment of Odd Meters in the History of Jazz Sopon Suwannakit1 Abstract Rhythmic Development of Jazz Has Grown In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis a Dissertation Submitted to the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University in Partial Fu

THE EXOTIC RHYTHMS OF DON ELLIS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PEABODY INSTITUTE OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS BY SEAN P. FENLON MAY 25, 2002 © Copyright 2002 Sean P. Fenlon All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Fenlon, Sean P. The Exotic Rhythms of Don Ellis. Diss. The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, 2002. This dissertation examines the rhythmic innovations of jazz musician and composer Don Ellis (1934-1978), both in Ellis’s theory and in his musical practice. It begins with a brief biographical overview of Ellis and his musical development. It then explores the historical development of jazz rhythms and meters, with special attention to Dave Brubeck and Stan Kenton, Ellis’s predecessors in the use of “exotic” rhythms. Three documents that Ellis wrote about his rhythmic theories are analyzed: “An Introduction to Indian Music for the Jazz Musician” (1965), The New Rhythm Book (1972), and Rhythm (c. 1973). Based on these sources a general framework is proposed that encompasses Ellis’s important concepts and innovations in rhythms. This framework is applied in a narrative analysis of “Strawberry Soup” (1971), one of Don Ellis’s most rhythmically-complex and also most-popular compositions. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to extend my heartfelt thanks to my dissertation advisor, Dr. John Spitzer, and other members of the Peabody staff that have endured my extended effort in completing this dissertation. Also, a special thanks goes out to Dr. H. Gene Griswold for his support during the early years of my music studies. -

Pressemappe 2016

PRESSEMITTEILUNG / 2. März 2016 20 Jahre palatia Jazz Festival „The Finest in Jazz“ Mit dem Sommer 2016 findet in der Zeit vom 25. Juni bis Ende Juli die 20. Festivalsaison an den wohl schönsten historischen Spielstätten in der Weinpfalz statt. Internationale Jazzstars und Deutsche Jazzensembles bieten ein aufregendes Musikprogramm. Zum Einlass ab 18.00 Uhr beginnt jeweils das Jazzkulinarium, bei welchem sich jeder Gast mit Wein und feinen Speisen auf die Konzertabende einstimmen kann. Am 19. Juni 1997 startete das erste Jazzfestival in der Weinstadt Deidesheim. Seinerzeit gab es in der Pfalz kaum Konzerte, die Jazz und jazzaffine Musik vorstellten. Bereits das erste Festival war binnen weniger Tage ausverkauft. Die Deidesheimer Winzerbetriebe stellten ihre schönen Weine vor und das älteste Gasthaus der Pfalz, „Die Kanne“ aus Deidesheim präsentierte eine genußvolle Auswahl von Speisen aus der mediterran‐pfälzischen Küche. Vor der Deidesheimer Stadthalle fand ein kulinarischer Markt statt, der ebenso Teil des Rahmenprogramms war und als „Markt der Genüsse“ bis heute weiterhin durchgeführt wird. Im ersten Festival spielten Albert Mangelsdorff, Wolfgang Dauner, Christof Lauer – sowie Klaus Doldingers Passport, Barbara Dennerlein und Tab Two mit Helmut Hattler und Joo Kraus. Der Anfang war gemacht. Das Festival hieß zu diesem Zeitpunkt Jazzette – Deidesheimer Jazztage und wurde noch ein weiteres Jahr unter diesem Namen fortgesetzt, bis es 1999 pfalzweit an einzigartigen historischen Plätzen der Pfalz unter dem Namen „palatia Jazz“ fortgesetzt wurde. Eine Konzertreihe von jährlich 10‐12 Konzerten – diese an unterschiedlichsten und unverwechselbaren Orten der Weinpfalz, wie die Villa Ludwigshöhe, die Klosterruine Limburg in Bad Dürkheim, der Krönungssaal in der Burg Trifels, der Festsaal im Hambacher Schloss, am Deutschen Weintor, im Park von Schloss Wachenheim usw. -

Reflection on Existing Cultural Imprint of Bruce Lee Lam Kwan-Yu Jeffrey

Reflection on Existing Cultural Imprint of Bruce Lee Lam Kwan-yu Jeffrey Further on my class presentation ‘Cultural Construction of Bruce Lee on Mass Media’, I would like to review my psychological change on perceiving existing cultural imprint of Bruce Lee after the MCS course via this paper. First of all, I would examine my feel throughout getting in touch with Bruce’s material in the course and reference, followed by dissecting why I would think that way, inducing the feeling. It would be a ‘feel, and think why’ process. I believe that would give some answers or reference for the reason of popularity of Bruce among the 80’s, after four decades of his death. Besides, I would source out the hidden culture imprint of Bruce around my life on different objects and analyse the formulation and impact of them to the world, enhancing my class presentation. It is mainly covered with a Hong Kong band Chochukmo, Japanese Jazz Pianist Hiromi Uehara, a video work from my current company and virtual character copied from him. I would like to find out the new influence of Bruce in recent years not directed by him, but created by the existing cultural construction of him authored by different parties of various fields. In the very first lessons, I once refused to admit there is any hagiography of Bruce. I believed it is his sincerity and bravery that attracts mass media to focus on him. I was too ideal before realizing how he is being consumed. As being born on the same birthday with him, I thought I could do the same like him, passing on his own spirit. -

The Jazz Educator's Magazine

OCTOBER 2019 OCTOBER THE JAZZ EDUCATOR’S MAGAZINE $4.99 Composing With Colors jazzedmagazine.com INSIDE Focus Session: Developing a Great Vibrato ‘Tearing Down the Silos’: Inside Aspen’s New Jazz ‘Boot Camp’ Collaboration Between Jazz Aspen Snowmass and the Frost School of Music spotlight C o m p o s i n g w i t h C o l o r s ALL PHOTOS COURTESY TELARC/CONCORD MUSIC GROUP MUSIC TELARC/CONCORD COURTESY PHOTOS ALL azz pianist and composer cover of a tune the pianist had Hiromi Uehara is a whirling been dying to do: the “Cantina Theme” from Star Wars. And the Jdervish of musical energy. Her By Bryan Reesman diverse recorded repertoire over the duo performed it their own special style last 16 years verifi es that claim. While she which went beyond the original melody. has released a fair number of solo albums, she Her collaboration with Castaneda is typical of also revels in collaborating with equally talented peers who how Hiromi interprets jazz, in which she implements diff erent allow her to widen her horizons. She already shares a Grammy approaches that range from the melodic to the textural. On her Award for performing with The Stanley Clarke Band on their 2010 new solo piano album Spectrum, one track fi nds her interpreting self-titled album, which won Best Contemporary Jazz Album at Gershwin in her own inimitable way while another has a boogie the Grammy Awards in 2011. feel to it. Going back in her catalog yields the same kind of re- I fi rst saw Hiromi live at the Montreal Jazz Festival in 2017 sults, with “Kung Fu World Champion,” from her sophomore al- where she played a concert with harp player Edmar Castaneda, bum Brain, serving up a dissonant, funky vibe. -

Holt Atherton Special Collections Ms4: Brubeck Collection

HOLT ATHERTON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MS4: BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 1: PAPERS SUBSERIES E: CLIPPINGS BOX 3a : REVIEWS, 1940s-1961 1.E.3.1: REVIEWS, 1940s a- “Jazz Does Campus Comeback but in new Guise it’s a ‘Combo,’” Oakland Tribune, 3-24-47 b- Jack Egan. “Egan finds jury…,” Down Beat, 9-10-47 c- “Local boys draw comment,” <n.s.> [Chicago], 12-1-48 d- Edward Arnow. “Brubeck recital is well-received,” Stockton Record, 1-18-49 e- Don Roessner. “Jazz meets J.S. Bach in the Bay Region,” SF Chronicle, 2- 13-49 f- Robert McCary. “Jazz ensemble in first SF appearance,” SF Chronicle, 3-6- 49 g- Clifford Gessler. “Snap, skill mark UC jazz concert,” <n.s.> [Berkeley CA], n.d. [4-49] h- “Record Reviews---DB Trio on Coronet,” Metronome, 9-49, pg. 31 i- Keith Jones. “Exciting and competent, says this critic,” Daily Californian, 12- 6-49 j- Kenneth Wastell. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-8-49 k- Dick Stewart. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-9-49 l- Ken Wales. “Letters to the editor,” Daily Californian, 12-14-49 m- “Record Reviews: The Month’s best [DB Trio on Coronet],” Metronome, Dec. 1949 n- “Brubeck Sounds Good” - 1949 o- Ralph J. Gleason, “Local Units Give Frisco Plenty to Shout About,” Down Beat, [1949?] 1.E.3.2: REVIEWS, 1950 a- “Record Reviews: Dave Brubeck Trio,” Down Beat, 1-27-50 b- Bill Greer, "A Farewell to Measure from Bach to Bop," The Crossroads, January 1950, Pg. 13 c- Keith Jones. “Dave Brubeck,” Bay Bop, [San Francisco] 2-15-50 d- “Poetic License in Jazz: Brubeck drops in on symphony forum, demonstrates style with Bach-flavored bop,” The Daily Californian, 2-27-50 e- Barry Ulanov. -

A Jazz Night with Hiromi (23 & 24 December) and a Viennese New Year (30 & 31 December)

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Date: 18 December 2019 The HK Phil Conjures Up a Festive Mood with Two Stylish Programmes: A Jazz Night with Hiromi (23 & 24 December) and A Viennese New Year (30 & 31 December) [18 December 2019, Hong Kong] For the upcoming festive season, the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra (HK Phil) brings two stylish programmes to audience in Hong Kong. In anticipation of Christmas celebrations, composer/jazz pianist HIROMI joins hands with fellow Japanese conductor Ryusuke Numajiri to share her music in two nights of jazz at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre Concert Hall on 23 & 24 December. And to bid farewell to the year 2019, British conductor Christopher Warren-Green teams up with Canadian/American coloratura soprano Sharleen Joynt to bring our audience a Viennese New Year in Hong Kong. Two performances will take place at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre Concert Hall: one each on 30 & 31 December. ********** A Jazz Night with HIROMI (23 & 24 December) “Jazz pianist and composer Hiromi Uehara is a whirling dervish of musical energy. Her diverse recorded repertoire over the last 16 years verifies that claim.” --- Jazzed Magazine What better Christmas present to suggest than to enjoy a dazzling display of virtuosity and compelling showmanship by HIROMI. On the two nights leading up to Christmas itself, the star Japanese jazz pianist and composer HIROMI brings her music to the stage of the HK Phil with conductor Ryusuke Numajiri, himself a strong advocate of contemporary music. Arguably the most famous musician in the Japanese jazz scene, HIROMI made her debut in 2003 and has 13 albums to her credit to date. -

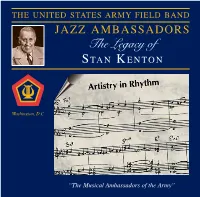

The Legacy of S Ta N K E N to N

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND JAZZ AMBASSADORS The Legacy of S TA N K ENTON Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Jazz Ambassadors is the Concerts, school assemblies, clinics, T United States Army’s premier music festivals, and radio and televi- touring jazz orchestra. As a component sion appearances are all part of the Jazz of The United States Army Field Band Ambassadors’ yearly schedule. of Washington, D.C., this internation- Many of the members are also com- ally acclaimed organization travels thou- posers and arrangers whose writing helps sands of miles each year to present jazz, create the band’s unique sound. Concert America’s national treasure, to enthusi- repertoire includes big band swing, be- astic audiences throughout the world. bop, contemporary jazz, popular tunes, The band has performed in all fifty and dixieland. states, Canada, Mexico, Europe, Ja- Whether performing in the United pan, and India. Notable performances States or representing our country over- include appearances at the Montreux, seas, the band entertains audiences of all Brussels, North Sea, Toronto, and New- ages and backgrounds by presenting the port jazz festivals. American art form, jazz. The Legacy of Stan Kenton About this recording The Jazz Ambassadors of The United States Army Field Band presents the first in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contri- butions to big band jazz. Designed primarily as educational resources, these record- ings are a means for young musicians to know and appreciate the best of the music and musicians of previous generations, and to understand the stylistic developments leading to today’s litera- ture in ensemble music. -

Review of Alchemy Sound Project

ALCHEMY SOUND PROJECT BASS MUSICIAN MAGAZINE JUNE 22 2018 Accomplished Composers — Erica Lindsay, Sumi Tonooka, Samantha Boshnack, Bassist David Arend, and Salim Washington — transcend barriers of distance and style in a compelling musical experience… Adventures in Time and Space, the second release by Alchemy Sound Project, blends jazz, classical and world music traditions in striking and inventive ways When Alchemy Sound Project initially came together, their mission seemed as elusive as the medieval mystics that inspired their name: after all, combining five distinctive composers, separated by miles and even continents, each melding jazz, classical and world music influences in their own unique ways, into a single ensemble that also played to their individual gifts as performers and improvisers – well, that all starts to make turning lead into gold seem like child’s play. Despite those challenges, Alchemy’s debut Further Explorations (the title suggesting that they were already looking forward, even their first time out), made an impressive impact, earning widespread critical acclaim and earning the band a place on DownBeat Magazine’s Best Albums of 2016 list. Many a collective ensemble has managed one great album before disbanding; the proof is in the longevity. Now, Alchemy returns with their second outing Adventures in Time and Space– due out June 15, 2018via Artists Recording Collective– and the results are even more compelling this time around. “We’re committed to each other,” says pianist Sumi Tonooka who originally masterminded the project. The five core members of Alchemy Sound Project were initially brought together by the Jazz Composers Orchestra Institute, a program of the American Composers Orchestra and the Center for Jazz Studies at Columbia University that encourages jazz composers to explore writing music for symphony orchestra. -

Hiromi a Japanese Jazz Prodigy finds Her Voice As She Returns to a Healing Home

MAY 2011 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM SPOTLIGHT sakiko nomura hiromi A Japanese jazz prodigy finds her voice as she returns to a healing home When a devastating earthquake had the impression that music makes people and tsunami struck Japan in March, many happy. i loved making people happy and touring artists canceled their plans to visit. wanted to keep doing that.” Japanese classical and jazz pianist hiromi, her latest album, Voice, is making people however, rearranged her touring plans to happy around the world. the album’s title, come home. “Bands have just stopped hiromi says, suggests its overall concept. coming, and i respect that decision,” “i wanted to capture people’s inner voices, she says from tokyo, where she has just and the screaming is represented in the completed a string of 18 benefit concerts. repeated piano notes,” she emphasizes. “i “But things are totally functioning in tokyo. wanted a three-dimensional sound. it was MAY 2011 sometimes the news broadcasts are much almost like the voice of the people was coming M MUSIC & MUSICIANS more dramatic than what it is. We have to me from here, there and everywhere, a normal life, but we’re trying to recover from every angle.” MAGAZINE emotionally and psychologically. there is hiromi plays other tracks, such as the not that much physical damage in tokyo, but groove-oriented “Flashback” and the moody, we have psychological damage.” minimalist “delusion,” with a controlled fury. Born hiromi uehara in hamamatsu, “When i listen to the album i can feel the story Japan, hiromi began playing classical piano from the first to last track, and that was what at 5 before gravitating toward jazz when i was the happiest about,” she says. -

Hiromi: the Trio Project Presentará Su Disco Spark En Marzo

Ciudad de México, martes 14 de febrero de 2017 HIROMI: THE TRIO PROJECT PRESENTARÁ SU DISCO SPARK EN MARZO Podría ser la última oportunidad para escuchar a este ensamble, pues sus integrantes anunciaron que harán una pausa indefinida Integrado por la pianista Hiromi Uehara, el baterista Simon Phillips y el bajista Hadrien Feraud, quien sustituye a Anthony Jackson La agrupación presentará su álbum más reciente, los próximos 30 y 31 de marzo Tras impactar con su virtuosismo y sofisticado estilo a las audiencias y la crítica internacionales, la pianista y compositora japonesa de jazz Hiromi Uehara y The Trio Project regresarán el 30 y 31 de marzo al Lunario, para presentar su más reciente disco, titulado Spark (2016). Podría ser la última oportunidad para escuchar el poderoso sonido de este ensamble en el foro alterno del Auditorio Nacional, pues sus integrantes anunciaron que posteriormente harán una pausa indefinida. A través de casi siete años, The Trio Project, originalmente conformado por la pianista Hiromi Uehara, el bajista Anthony Jackson y el baterista Simon Phillips, se consolidó como uno de los ensambles contemporáneos de jazz más trascendentes, gracias a su refrescante propuesta sonora en la que fusiona rock progresivo, hard bop, ragtime, blues y funk. En esta ocasión, Hadrien Feraud estará en el bajo, en sustitución de Anthony Jackson, quien por motivos de salud no podrá participar en este concierto. Sin embargo, tanto Feraud como Hiromi Uehara y Simon Phillips han prometido un concierto dinámico, con el que la improvisación cruzará la línea de lo ordinario, para rendir homenaje a Anthony Jackson, a quien el bajista considera una de sus mayores influencias. -

Adopted Textbook List 2002.Pdf (6.153Mb)

2002-2003 INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS BULLETIN KINDERGARTEN - 5 Table of Contents PreKindergarten through Grade 2 Programs Adopted by the State of Texas 2002-2003 097] PreKindergarten Learning Systems, PreKindergarten (1995 - 2001 - 2003) I 0981 Kindergarten Learning Systems, Kindergarten (1995 2001- 1 0004 English Language Arts & Reading, Kindergarten 1 0007 Spanish Language Arts & Reading, Kindergarten (2000 - 2006) 2 0040 Language Arts & Reading, Kindergarten CONSUMABLES (2000 - 2006) 3 0043 Language Arts & Reading, Kindergarten CONSUMABLES (2000 - 3 0120 Mathematics, Kindergarten (1999 - 2005) 4 0123 Mathematics Spanish, Kindergarten (]999 2005) 5 1004 English Language Arts & Reading, Grade I (2000 - 6 1007 Language Arts & Reading, Grade 1 (2000 - 2006) 7 1020 Handwriting, Grade 1 (1993 - 1999 - 2000 - 2004) 7 1030 Spelling, Grade 1 (1998 - 7 1040 English Language Arts and Reading, Grade I, CONSUMABLES (2000 8 ]043 Spanish Language Arts & Reading, Grade 1, CONSUMABLES (2000 - 9 1051 as a Second Language,G rade 1 (1997 - 2003) 9 1120 Mathematics, Grade I (1999 - 2005) 10 1123 Mathematics Spanish, Grade 1 (1999- 11 1200 Elementary Science Textbooks, Grade 1 (2000 - 2006) 12 1230 Elementary Science Textbooks, Spanish, Grade 1 (2000 - 12 1321 Social Studies, Grade 1 (1997 - 2003) 13 1323 Socia] Studies Spanish, Grade 1 (1997 - 13 1451 Spanish as a Second Language, Grade I (1997 - 14 1710 Health Teacher's Resource Books,Gra des 1-3 (1987 - 1993 - 1997 - 2000 - 14 1800 Art, Grade 1 (1998 - 14 1828 General Music Learning Systems, Grade 1 15 1830 -

Jazz Horn Top

99 Historically Significant Jazz Recordings with Horn compiled by Dr. Steven Schaughency Large Ensemble, Big Band recordings group leader name of original recording horn player(s) Brubeck, Dave Time Changes ??? Davis, Miles The Complete Birth of the Cool Junior Collins, Gunther Schuller, Sandy Siegelstein Davis, Miles Porgy and Bess Willie Ruff, Gunther Schuller, Julius Watkins Evans, Gil New Bottle, Old Wine Julius Watkins Evans, Gil The Gil Evans Orchestra Plays the John Clark, Peter Gordon Music of Jimi Hendrix Evans, Gil Strange Fruit John Clark Ferguson, Maynard The Blues Roar Ray Alonge, Jimmy Buffington Ferguson, Maynard Conquistador Don Corrado, Brooks Tillotson Gillespie, Dizzy Gillespiana/Carnegie Hall Concert John Barrows, Dick Berg, Jimmy Buffington, Al Richman, Gunther Schuller, Julius Watkins Gruntz, George Blues’n Dues et cetera John Clark, Jerry Peel Johnson, J. J. The Brass Orchestra Bob Carlisle, John Clark, Chris Komer, Marshall Sealy Jones, Quincy The Great Wide World of Quincy Julius Watkins Jones Jones, Quincy The Quintessence Jimmy Buffington, Ray Alonge, Earl Chapin, Julius Watkins Jones, Thad New Life Ray Alonge, Jimmy Buffington, Earl Chapin, Peter Gordon, Julius Watkins Jones, Thad Suite for Pops Ray Alonge, Jimmy Buffington, Earl Chapin, Peter Gordon, Julius Watkins Kaye, Joel New York Neophonic Orchestra Ray Alonge, Dick Berg, Virginia Benz, John Clark, Dale Cleavenger, Ed Dieck, Francisco Donaruma, Sheldon Henry, Brooks Tillotson, Greg Williams Kenton, Stan Adventures in Jazz Mellophoniums: Dwight Carver,