09/18 Vol. 6 Guilty Pleasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

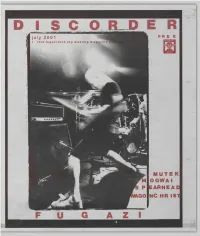

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Outcry to Demilitarize the Police and Politics

PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT #3036 WHITE PLAINS NY Vol. VI, No. XXXIV Thursday August 28, 2014 • $1.00 Westchester’s Most Influential Weekly NANCY KING Confessions of a Fitness Addict Page 10 GLENN SLABY Suicide: Some Thoughts Page 11 RICH MONETTI Why Government A Perfect Red Storm Page 14 Openness Matters JOHN MCMULLEN The Future? By Hon. LEE HAMILTON, Page 2 Page 15 Outcry to Opt-Out Forms Mailed to Permit Holders Demilitarize Putnam County, Page 5 JOHN SIMON the Police and Strategic Political Women Playwrights Politics Argument Page 16 LUKE HAMILTON By Hon. RICHARD BRODSKY, Page 2 for the A Pavlovian Response A Wussbag Worldview Minimum Page 18 Wage SHERIF AWAD Sugar On the Side By Prof. OREN LEVIN-WALDMAN, Page 3 Page 20 WWW.WESTCHESTERGUARDIAN.COM Page 2 THE WESTCHESTER GUARDIAN ThursdaY, August 28, 2014 Of Significance Feature Section ...................................................................................................................2 Yorktown Grange Fair..................................................................................................10 Center on Congress ........................................................................................................2 Health ...........................................................................................................................10 Politics .............................................................................................................................2 Music ............................................................................................................................12 -

2011 Edition 1 the Morpheus Literary Publication

The Morpheus 2011 Edition 1 The Morpheus Literary Publication 2011 Edition Sponsored by the Heidelberg University English Department 2 About this publication Welcome to the Fall 2011 edition of the Morpheus, Heidelberg University’s student writing magazine. This year’s issue follows the precedents we established in 2007: 1) We publish the magazine electronically, which allows us to share the best writing at Heidelberg with a wide readership. 2) The magazine and the writing contest are managed by members of English 492, Senior Seminar in Writing, as an experiential learning component of that course. 3) The publication combines the winning entries of the Morpheus writing contest with the major writing projects from English 492. Please note that Morpheus staff members were eligible to submit entries for the writing contest; a faculty panel judged the entries, which had identifying information removed before judging took place. Staff members played no role in the judging of the contest entries. We hope you enjoy this year’s Morpheus! Dave Kimmel, Publisher 3 Morpheus Staff Emily Doseck................Editor in Chief Matt Echelberry.............Layout Editor Diana LoConti...............Contest Director Jackie Scheufl er.............Marketing Director Dr. Dave Kimmel............Faculty Advisor Special thanks to our faculty judges: Linda Chudzinski, Asst. Professor of Communication and Theater Arts; Director of Public Relations Major Dr. Doug Collar, Assoc. Professor of English & Integrated Studies; Assoc. Dean of the Honors Program Dr. Courtney DeMayo, Asst. Professor of History Dr. Robin Dever, Asst. Professor of Education Tom Newcomb, Professor of Criminal Justice and Political Science Courtney Ramsey, Adjunct Instructor of English Heather Surface, Adjunct Lecturer, Communication and Theater Arts; Advisor for the Kilikilik Dr. -

Australian Gay Rugby Team in Sporting First to Be Making History

ANO INDEPENDENTU VOICE FOR THE TLESBIAN, GAY, BISEXUAL, AND TRANSGENDER COMMUNITIES July 11, 2014 | Volume XII, Issue 5 Pro-LGBT Candidates Face Off in Howard County BY STEVE CharING members helped sway his views towards tions submitted via online and It’s not often you see a Republican and a supporting marriage equality. He said fair- social media. No live ques- Democrat tout their pro-LGBT bonafides ness and equal rights are his main priori- tions from the audience were during a political debate but that’s exactly ties as taught by his father, and these val- solicited. The questions cov- what happened at a PFLAG-Howard Coun- ues transcend political parties. “I had been ered housing and develop- ty forum in Columbia on July 8. It was the the only Republican to show up at PFLAG ment, redevelopment, transit, first post-primary forum of the campaign in picnics,” he pointed out. budget economic develop- the county. Watson also asserted her relationship ment, employment, and hous- Republican Allan H. Kittleman, a former with PFLAG and the LGBT community ing for low-income residents, state senator who is vying to succeed Ken ever since she was on the county’s school tax rates, county services Ulman as the next county executive, and board. Her son was a classmate at school needing investment and at- his opponent, Democrat councilwoman with the transgender child of a member of tention, education and com- Courtney Watson, shared their visions for PFLAG and encouraged Watson to sup- mon core, environment, and the county on a wide swath of issues. -

Nickelodeon Greenlights Fourth Season of Hit Music Comedy Series Big Time Rush

Nickelodeon Greenlights Fourth Season Of Hit Music Comedy Series Big Time Rush Network Orders 13 Episodes with Production Beginning Q1 2013 NEW YORK, Aug. 6, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- As music sensation Big Time Rush crosses the U.S. this summer performing to sold- out audiences and arenas, and with their hit single "Windows Down" climbing the charts, Nickelodeon has ordered a fourth season of their self-titled hit comedy series Big Time Rush. Created by Scott Fellows and produced in partnership with Sony Music, the series chronicles the adventures of four best friends living the dream in Los Angeles, balancing their newfound fame, fans, music and girlfriends. Starring Kendall Schmidt, James Maslow, Carlos Pena and Logan Henderson, Big Time Rush is slated to commence production on 13 episodes early 2013 in Los Angeles. (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20120806/NY52671) The band's summer anthem "Windows Down," sparked by their strongest first week sales to date, is trending to be their biggest hit yet at radio, digital sales providers and online, with their music video approaching nearly three million views. "Windows Down" will be Big Time Rush's third consecutive charted single at Pop radio. The "Big Time Summer Tour" has the band entertaining fans in 60 cities, making appearances across the U.S., Canada and South America. Their debut, gold- certified BTR and follow-up album Elevate, both entered the Billboard charts in the top 15 and currently total over 1.25 million albums sold worldwide and 3.5 million singles in the U.S. "Our viewers continue to love the stories, music and comedic misadventures of Kendall, James, Carlos and Logan. -

Across the Stream

Across the Stream By E. F. Benson Across the Stream CHAPTER I Certain scenes, certain pictures of his very early years of childhood, stood out for Archie like clear sunlit peaks above the dim clouds that shrouded the time when the power of memory was only beginning to germinate. He had no doubt (and was probably right about it) as to which the earliest of those was: it was the face of his nurse Blessington, leaning over his crib. She held a candle in her hand which a little dazzled him, but the sight of her face, tender and anxious, and divinely reassuring, was the point of that memory. He had been asleep, and had awoke with a start, and, finding himself alone in the midst of the immense desolation of the dark that pressed on him like an invader from all sides, he had lifted up his voice and yelled. Then, as by a conjuringtrick, Blessington had appeared with her comforting presence that quite robbed the dark of its terrors. It must still have been early in the night, for she had not yet gone to bed, and had on above her smooth grey hair her cap with its adorable blue ribands in it. At her throat was the brooch made of the same stuff as the shining shillings with which a year or two later she bought the buns and spongecakes for tea. He remembered no more than that; he knew nothing of what she had said: the whole of that memory consisted in the fact of the secure comfort and relief which her face brought. -

August 2016 1 Periodical Postageperiodical Paid at Boston, New York

SHOULD YOU HIRE A PROFESSIONAL GENEALOGIST?POLISH AMERICAN — JOURNAL PAGE 15• AUGUST 2016 www.polamjournal.com 1 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE JOURNAL AN ESSENTIAL EDITION: FROM PADEREWSKI TO ESTABLISHED 1911 AUGUST 2016 • VOL. 105, NO. 8 | $2.00 www.polamjournal.com PENDERECKI — PAGE 6 WHAT BREXIT MAY MEAN FOR POLAND • GET READY FOR POLISH HERITAGE MONTH • CATHOLIC LEAGUE APPEAL HEADING INTO THE FUTURE • FAREWELL TO AMBASSADOR SCHNEPF • AN AMERICAN FACE IN POLISH POLITICS BISHOP ZUBIK AND GUN CONTROL • THE WOMEN OF THE UPRISING • CHICAGO’S POLISH POPULATION CHANGE NATO Summit — a Major Breakthrough Polish Newsmark Communities RUSSIA USES NATO SCARES TO KEEP ITS PEOPLE in UK Targeted IN LINE – FOREIGN MINISTER. The Russian leadership rejects all explanations that NATO is a defensive alliance with Abuse that poses no threat to Russia, because the Kremlin needs a state of confl ict for domestic political purposes, Polish After Brexit Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski said during the LONDON — The Pol- North Atlantic Alliance’s recent Warsaw summit. “If the ish embassy in London said Kremlin told citizens of the Russian Federation, there was it was deeply concerned by no longer any threat of a NATO invasion, people would what it said were recent in- soon start pressing for a better life and more freedom,” he cidents of xenophobic abuse explained. “Considering Russia’s great mineral wealth, it directed against the Polish could be one of the world’s richest countries were it not for community since Britain all the corruption.” voted to leave the European Union. -

Sweet Songs from Crazy Heart 1 Sweet Songs from Crazy by Sarah Skates Heart 2 Bobby Karl Works the New Movie Crazy Heart Drawn Less Media Lady Antebellum No

page 1 Friday, January 15, 2010 Table of Contents Sweet Songs From Crazy Heart 1 Sweet Songs From Crazy by Sarah Skates Heart 2 Bobby Karl Works The New movie Crazy Heart drawn less media Lady Antebellum No. 1 was not filmed in Nashville, attention with his un- Party but its country music theme billed role as “Tommy 3 Griffith Rejoins Magic is drawing a lot of local Sweet,” the superstar Mustang interest. A premiere held who got his start in 3 Roots Music Exporters Hits First $1 Million Year Tuesday night (1/12) at Blake’s band. Maggie 4 Flammia Exits UMG the Green Hills movie Gyllenhall is “Jean” a 4 King Offers Inspiration theatre attracted members journalist, and Robert And Help of the industry and Duvall plays Blake’s bar- 4 DISClaimer celebrities alike; all owning friend. Writer- 5 Spin Zone/Chart Data curious about the flick director Scott Cooper 7 Programmer Playlist which is generating adapted the story from 8 On The Road... Oscar buzz for star Jeff Thomas Cobb’s novel by 9 CountryBreakout™ Chart Bridges and the theme Jeff Bridges the same name. song penned by T Bone Photo: Erika The film’s roots- Respect Intellectual Property: Goldring MusicRow transmissions in email and Burnett and Ryan Bingham. grounded soundtrack was file form plus online passwords, are In the movie Bridges plays produced by renowned intended for the sole use of active subscribers only and protected under hard-living country singer- talents Burnett and Stephen the copyright laws of the United States. Resending or sharing of such intellectual songwriter “Bad Blake.” With the Bruton, who also contributed property to unauthorized individuals tagline “The Harder The Life, The as songwriters and and/or groups is expressly forbidden. -

Závěrečná Absolventská Práce Ix

ZÁVĚREČNÁ ABSOLVENTSKÁ PRÁCE IX. ročník Big Time Rush, Dagmar Vašková Toto téma jsem si vybrala, protože je to moje nejoblíbenější skupina a mám ráda jejich písničky. Obsah O skupině Historie James Maslow Carlos Pena Logan Henderson Kendall Schmidt Mazlíčci Alba Názvy písní - 1 - ZÁVĚREČNÁ ABSOLVENTSKÁ PRÁCE IX. ročník Big Time Rush, Dagmar Vašková O Skupině Big Time Rush (známí jako BTR) je americká pop rocková chlapecká skupina založená v roce 2009. Jejími členy jsou Kendall Schmidt, James Maslow, Carlos Pena Jr. a Logan Henderson. Skupina Big Time Rush byla založena díky stejnojmennému televiznímu seriálu stanice Niklodeon. Po vydání několika propagačních singlů vydala kapela v říjnu 2010 své první album s názvem B.T.R., které získalo zlatou desku za 500000 prodaných kopií. Jejich druhé album vyšlo v listopadu 2011. - 2 - ZÁVĚREČNÁ ABSOLVENTSKÁ PRÁCE IX. ročník Big Time Rush, Dagmar Vašková Historie Big Time Rush podepsali v roce 2009 nahrávací smlouvu. Jejich debitový singl „Big Time Rush“ vyšel v listopadu 2009, poprvé byl uveden během hodinové speciální ukázky seriálu. V současné době je seriálovou úvodní znělkou. BTR také vydali další propagační singly jako „City is Ours“ a „Famous“. V listopadu 2010 oznámili Big Time Rush speciální vánoční episodu seriálu. Skupina též přezpívala s Mirandou Cosarove píseň „All I Want For Christmas Is You“, písnička měla premiéru v onom vánočním díle „Big Time Christmas“. - 3 - ZÁVĚREČNÁ ABSOLVENTSKÁ PRÁCE IX. ročník Big Time Rush, Dagmar Vašková James Maslow James David Maslow je americký zpěvák, herec, taneční a model. Hraje na kytaru, klavír a bicí. Narodil se v New Yorku (16. července 1990). Má bratra Philipa a sestru Ali Thom. -

View Song List

Piano Bar Song List 1 100 Years - Five For Fighting 2 1999 - Prince 3 3am - Matchbox 20 4 500 Miles - The Proclaimers 5 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin' Groovy) - Simon & Garfunkel 6 867-5309 (Jenny) - Tommy Tutone 7 A Groovy Kind Of Love - Phil Collins 8 A Whiter Shade Of Pale - Procol Harum 9 Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) - Nine Days 10 Africa - Toto 11 Afterglow - Genesis 12 Against All Odds - Phil Collins 13 Ain't That A Shame - Fats Domino 14 Ain't Too Proud To Beg - The Temptations 15 All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor 16 All Apologies - Nirvana 17 All For You - Sister Hazel 18 All I Need Is A Miracle - Mike & The Mechanics 19 All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket 20 All Of Me - John Legend 21 All Shook Up - Elvis Presley 22 All Star - Smash Mouth 23 All Summer Long - Kid Rock 24 All The Small Things - Blink 182 25 Allentown - Billy Joel 26 Already Gone - Eagles 27 Always Something There To Remind Me - Naked Eyes 28 America - Neil Diamond 29 American Pie - Don McLean 30 Amie - Pure Prairie League 31 Angel Eyes - Jeff Healey Band 32 Another Brick In The Wall - Pink Floyd 33 Another Day In Paradise - Phil Collins 34 Another Saturday Night - Sam Cooke 35 Ants Marching - Dave Matthews Band 36 Any Way You Want It - Journey 37 Are You Gonna Be My Girl? - Jet 38 At Last - Etta James 39 At The Hop - Danny & The Juniors 40 At This Moment - Billy Vera & The Beaters 41 Authority Song - John Mellencamp 42 Baba O'Riley - The Who 43 Back In The High Life - Steve Winwood 44 Back In The U.S.S.R.