Return of Endemic Plant Populations on Trindade Island, Brazil, with Comments on the Fauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print 04/02 April

From the Rarities Committee’s files: Rare seabirds and a record of Herald Petrel Ian Lewington ABSTRACT Rare seabirds are often extremely hard to identify, and a significant part of the problem is that, when observed from land, circumstances are typically very difficult. In many cases, one or more of the following drawbacks applies: the weather conditions are poor, views are distant and brief, and photographic evidence is impossible. For these same reasons, records of rare seabirds are also difficult to assess, particularly so if they concern what would be a ‘first for Britain’ for the species in question.This was the case when a probable Herald Petrel Pterodroma arminjoniana was seen off Dungeness, Kent, in January 1998. In this paper, the circumstances and the assessment of that record are described, and, more generally, the level of supporting evidence which is necessary for acceptance of records of rare seabirds is discussed. 156 © British Birds 95 • April 2002 • 156-165 Rare seabirds and a record of Herald Petrel are seabirds present difficulties in many panic was beginning to set in. Had we missed ways. They are difficult to find, and most it? A few seconds later, the mystery seabird Robservers will spend hundreds of hours came into our field of view, trailing behind a ‘sifting through’ common species before Northern Gannet Morus bassanus and flying encountering a rarity. They are difficult to iden- steadily west, low over the water, about 400 m tify, not least because the circumstances in offshore. which they are seen usually mean that, com- At the time of the observation the light was pared with most other birding situations, views dull but clear, in fact excellent for observing are both distant and brief, and the observer is colour tones. -

Bancodosabrolhos Cad

1 Banco dos Abrolhos & Cadeia Vitória-Trindade 3 Proposta de reconhecimento de uma Reserva da Biosfera Marinha na Costa Central do Brasil Banco dos Abrolhos & Cadeia Vitória-Trindade Proposta de reconhecimento de uma Reserva da Biosfera Marinha na Costa Central do Brasil 3 AGRADECIMENTOS EQUIPE RBMA Comites Estaduais da RBMA na Bahia e Espírito Santo Secretário Executivo : Luiz Alberto Bucci Colegiado Mar da RBMA Apoio técnico : Grupo Conexão Abrolhos-Trindade Ana Lopez Bahia, Espírito Santo e Rio de Janeiro Heloisa Dias Marcelo M. Amaral Postos Avançados da RBMA Nilson Máximo Parque Nacional Marinho de Abrolhos Pedro Castro Base TAMAR-Linhares Apoio Administrativo: Secretaria de Biodiversidade e Fernando Capello Floresta / MMA Luan Vasco Leiz da Silva Rosa UNESCO - Oficina Montevideo Oswaldo Henrique de Souza Fotos e Mapas: Editoração Grafica: Arquivos Voz da Natureza & RBMA Felipe Sleiman Sumário APRESENTAÇÃO .................................................................................... 06 I47b INSTITUTO AMIGOS DA RESERVA DA BIOSFERA DA MATA ATLÂNTICA 1. UMA RESERVA DA BIOSFERA MARINHA NO BRASIL ............ 08 Banco dos Abrolhos & Cadeia Vitoria-Trindade: Proposta de reconhecimento de uma Reserva da Biosfera marinha na Costa Central do Brasil. 2. ECOSSISTEMAS E AMBIENTES DA REGIÃO .............................. 12 Organização Clayton Ferreira Lino; Heloisa Dias São Paulo: IA-RBMA, 2014 63p. ; il. 27 cm 3. ASPECTOS DA BIODIVERSIDADE ............................................... 18 Disponível também em: http://www.rbma.org.br 4. SERVIÇOS ECOSSISTÊMICOS ........................................................ 30 Bibliografia 5. PRINCIPAIS AMEAÇAS A BIODIVERSIDADE ............................. 34 ISBN: 978-85-68863-00-8 1. Reserva Biosfera Marinha-Brasil 2. Ecossistemas-ambientais 6. ÁREAS PROTEGIDAS ........................................................................ 42 3. Biodiversidade Marinha 4. Áreas protegidas. 5. Sustentabilidade I. Lino Clayton Ferreira, org. II. Mazzei Eric Freitas, org.III. -

Pterodromarefs V1-5.Pdf

Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithological Congress’ World Bird List. A few differences occur with regard to the number and treatment of subspecies where some are treated as full species. Version Version 1.5 (5 May 2011). Cover With thanks to Kieran Fahy and Dick Coombes for the cover images. Species Page No. Atlantic Petrel [Pterodroma incerta] 5 Barau's Petrel [Pterodroma baraui] 17 Bermuda Petrel [Pterodroma cahow] 11 Black-capped Petrel [Pterodroma hasitata] 12 Black-winged Petrel [Pterodroma nigripennis] 18 Bonin Petrel [Pterodroma hypoleuca] 19 Chatham Islands Petrel [Pterodroma axillaris] 19 Collared Petrel [Pterodroma brevipes] 20 Cook's Petrel [Pterodroma cookii] 20 De Filippi's Petrel [Pterodroma defilippiana] 20 Desertas Petrel [Pterodroma deserta] 11 Fea's Petrel [Pterodroma feae] 8 Galapágos Petrel [Pterodroma phaeopygia] 17 Gould's Petrel [Pterodroma leucoptera] 19 Great-winged Petrel [Pterodroma macroptera] 3 Grey-faced Petrel [Pterodroma gouldi] 4 Hawaiian Petrel [Pterodroma sandwichensis] 17 Henderson Petrel [Pterodroma atrata] 16 Herald Petrel [Pterodroma heraldica] 14 Jamaica Petrel [Pterodroma caribbaea] 13 Juan Fernandez Petrel [Pterodroma externa] 13 Kermadec Petrel [Pterodroma neglecta] 14 Magenta Petrel [Pterodroma magentae] 6 Mottled Petrel [Pterodroma inexpectata] 18 Murphy's Petrel [Pterodroma ultima] 6 Phoenix Petrel [Pterodroma alba] 16 Providence Petrel [Pterodroma solandri] 5 Pycroft's Petrel [Pterodroma pycrofti] 21 Soft-plumaged Petrel [Pterodroma mollis] 7 Stejneger's Petrel [Pterodroma longirostris] 21 Trindade Petrel [Pterodroma arminjoniana] 15 Vanuatu Petrel [Pterodroma occulta] 13 White-headed Petrel [Pterodroma lessonii] 4 White-necked Petrel [Pterodroma cervicalis] 18 Zino's Petrel [Pterodroma madeira] 9 1 General Bailey, S.F. et al 1989. Dark Pterodroma petrels in the North Pacific: identification, status, and North American occurrence. -

Bugoni 2008 Phd Thesis

ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF ALBATROSSES AND PETRELS AT SEA OFF BRAZIL Leandro Bugoni Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, at the Institute of Biomedical and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow. July 2008 DECLARATION I declare that the work described in this thesis has been conducted independently by myself under he supervision of Professor Robert W. Furness, except where specifically acknowledged, and has not been submitted for any other degree. This study was carried out according to permits No. 0128931BR, No. 203/2006, No. 02001.005981/2005, No. 023/2006, No. 040/2006 and No. 1282/1, all granted by the Brazilian Environmental Agency (IBAMA), and International Animal Health Certificate No. 0975-06, issued by the Brazilian Government. The Scottish Executive - Rural Affairs Directorate provided the permit POAO 2007/91 to import samples into Scotland. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I was very lucky in having Prof. Bob Furness as my supervisor. He has been very supportive since before I had arrived in Glasgow, greatly encouraged me in new initiatives I constantly brought him (and still bring), gave me the freedom I needed and reviewed chapters astonishingly fast. It was a very productive professional relationship for which I express my gratitude. Thanks are also due to Rona McGill who did a great job in analyzing stable isotopes and teaching me about mass spectrometry and isotopes. Kate Griffiths was superb in sexing birds and explaining molecular methods again and again. Many people contributed to the original project with comments, suggestions for the chapters, providing samples or unpublished information, identifyiyng fish and squids, reviewing parts of the thesis or helping in analysing samples or data. -

Molecular Ecology of Petrels

M o le c u la r e c o lo g y o f p e tr e ls (P te r o d r o m a sp p .) fr o m th e In d ia n O c e a n a n d N E A tla n tic , a n d im p lic a tio n s fo r th e ir c o n se r v a tio n m a n a g e m e n t. R u th M a rg a re t B ro w n A th e sis p re se n te d fo r th e d e g re e o f D o c to r o f P h ilo so p h y . S c h o o l o f B io lo g ic a l a n d C h e m ic a l S c ie n c e s, Q u e e n M a ry , U n iv e rsity o f L o n d o n . a n d In stitu te o f Z o o lo g y , Z o o lo g ic a l S o c ie ty o f L o n d o n . A u g u st 2 0 0 8 Statement of Originality I certify that this thesis, and the research to which it refers, are the product of my own work, and that any ideas or quotations from the work of other people, published or otherwise, are fully acknowledged in accordance with the standard referencing practices of the discipline. -

The Marine Biodiversity and Fisheries Catches of the Pitcairn Island Group

The Marine Biodiversity and Fisheries Catches of the Pitcairn Island Group THE MARINE BIODIVERSITY AND FISHERIES CATCHES OF THE PITCAIRN ISLAND GROUP M.L.D. Palomares, D. Chaitanya, S. Harper, D. Zeller and D. Pauly A report prepared for the Global Ocean Legacy project of the Pew Environment Group by the Sea Around Us Project Fisheries Centre The University of British Columbia 2202 Main Mall Vancouver, BC, Canada, V6T 1Z4 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Daniel Pauly RECONSTRUCTION OF TOTAL MARINE FISHERIES CATCHES FOR THE PITCAIRN ISLANDS (1950-2009) ...................................................................................... 3 Devraj Chaitanya, Sarah Harper and Dirk Zeller DOCUMENTING THE MARINE BIODIVERSITY OF THE PITCAIRN ISLANDS THROUGH FISHBASE AND SEALIFEBASE ..................................................................................... 10 Maria Lourdes D. Palomares, Patricia M. Sorongon, Marianne Pan, Jennifer C. Espedido, Lealde U. Pacres, Arlene Chon and Ace Amarga APPENDICES ............................................................................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX 1: FAO AND RECONSTRUCTED CATCH DATA ......................................................................................... 23 APPENDIX 2: TOTAL RECONSTRUCTED CATCH BY MAJOR TAXA ............................................................................ -

Sightings of Humpback Whales on the Vitória-Trindade Chain and Around Trindade Island, Brazil

NOTE BRAZILIAN JOURNAL OF OCEANOGRAPHY, 60(3):455-459, 2012 SIGHTINGS OF HUMPBACK WHALES ON THE VITÓRIA-TRINDADE CHAIN AND AROUND TRINDADE ISLAND, BRAZIL Salvatore Siciliano 1, Jailson F. de Moura 1, Henrique R. Filgueiras 2, Paulo P. Rodrigues 3and Nilamon de Oliveira Leite Jr. 4 1Grupo de Estudos de Mamíferos Marinhos da Região dos Lagos (GEMM-Lagos), Departamento de Endemias Samuel Pessoa, Escola Nacionalde Saúde Pública/FIOCRUZ. Rua Leopoldo Bulhões, 1.480 –6º. andar, sala 620, Manguinhos– 21041-210, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 2Reserva Biológica de Comboios/Projeto Tamar, Caixa Postal 105, 29900-970 – Regência, Linhares, ES Brazil 3Instituto Ecomaris, Rua Renato Nascimento Daher Carneiro, 780.Condomínio Village, Edifício Delacroix, apto 203. Ilha do Boi – 29052-730 Vitória, ES, Brazil. 4Projeto Tamar/ICMBio, Av. Paulino Müller, 1111, Jucutuquara – 29040-715 Vitória, ES, Brazil *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Descriptors : Megaptera novaeangliae , Trindade Island; Brazil, Sightings, Migration. Descritores: Megaptera novaeangliae , Ilha de Trindade, Brasil, Avistagem, Migração. The Trindade and Martim Vaz Antarctic feeding activity extends from November to islands belong to an archipelago located 1,140 km east at least April (STONE; HAMMER, 1988; SECCHI et of Vitória, Espírito Santo State, Brazil, in the Southern al., 2001). Additionally, occasional sightings have Atlantic Ocean. The archipelago consists of six islands been reported in the Fernando de Noronha of which Trindade (20°30’S and 29°18’W), with an Archipelago (~3°S) and off southern and south-eastern area of 10.1 km², is the largest and Martim Vaz, with Brazil (e.g. LODI, 1994; PIZZORNO et al., 1998). an area of 0.3 km², the second in size. -

Herald Petrel New to the West Indies

EXTRALIMITAL RECORD Herald Petrel new to the West Indies Michael Gochfeld,Joanna Burger, Jorge Saliva, and Deborah Gochfeld (Pterodroma)are bestrepresented SinA southGROUP temperate THEGADFLY and subantarc-PETRELS tic waterswith a few speciesbreeding on tropicalislands in the Central Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.In the West Indies,the only member of this genusis the Black-cappedPetrel (P hasitata), which breeds in the Greater Antilles and perhaps still in the Lesser Antilles. A dose relative,the endangeredBermuda (P..cahow) breeds in Bermuda. On July 12, 1986, while studyingthe breeding Laughing Gulls (Larus atri- cilia), Royal Terns,and SandwichTerns (Sterna maxima and S. sandvicensis)on Cayo Lobito, in the Culebra National Wildlife Refuge, about 40 kilometers eastof Fajardo,Puerto Rico, we flushed an all-dark petrel from a scrapeamong the nestingterns. As soon as the bird wheeled around we realized that it was a petrel, and not the familiar Sooty Shearwater(Puj•nus griseus),a species Figure 1. Dark-phasePterodroma landing among Laughing Gulls on Cayo Lobito. Culebra, which would itselfbe extremelyunusual PuertoRico. Note the ashygray undersurface of theprimary.feathers, ending in longnarrow at Culebra. Compared to a shearwater, "digital" extensionsthat are the pale areas of the inner websof theprimaries. The greater the petrelappeared to havea largerhead underwingcoverts are pale with a narrowdark tip that showsas thefaint wavybar at the base of theprimaries. The Iongishtail and shortishbill are apparent. and a longerand slightlywedge-shaped tail. It did not showthe conspicuouspale wing linings of the Sooty Shearwater (Fig. 1). The bird circled rapidly, first low over the water and then wheeling high overthe rocky islet,before return- ing to its scrapeamong the gulls and terns. -

Conservation Advice Pterodroma Arminjoniana

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister’s delegate approved this conservation advice on 01/10/2015 Conservation Advice Pterodroma arminjoniana Round Island petrel Conservation Status Pterodroma arminjoniana (Round Island petrel) is listed as Critically Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cwlth) (EPBC Act). The species is eligible for listing as Critically Endangered as, prior to the commencement of the EPBC Act, it was listed as Critically Endangered under Schedule 1 of the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 (Cwlth). Garnett et al., (2011) reviewed the conservation status of the Round Island petrel and considered considered the single bird found on Cocos (Keeling) Island and identified as P. arminjoniana by Garnett and Crowley (2000), as likely to have been P. heraldica. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee are using the findings of Garnett et al., (2011) to consider whether reassessment of the conservation status of each of threatened birds listed under the EPBC Act is required. Description The gadfly petrels (Procellariidae: Pterodroma spp.) are a group of highly oceanic seabirds, comprising some 30 species, that are complex in plumage and taxonomy (Nelson 1980). Found throughout the ocean basins of the world, they are widely distributed in the tropics and sub-tropics, but with some species breeding in the subantarctic zone (Warham 1990). They are adapted to a highly aerial and oceanic life, and possess short sturdy bills adapted for seizing soft prey at the surface, and unusual helicoidally twisted intestines. The function of the twisted intestines is obscure but believed to assist in digesting marine animals that have an unusual biochemistry (Imber 1985, Kuroda 1986). -

Geochemical Evolution of Soils Developed from Pyroclastic Rocks of Trindade Island, South Atlantic

Geochemical evolution of soils developed from pyroclastic rocks of Trindade Island, South Atlantic Ana Carolina Campos Mateus, Angélica Fortes Drummond Chicarino Varajão, Fábio Soares De Oliveira, Sabine Petit, Carlos Ernesto Gonçalves Reynaud Schaefer To cite this version: Ana Carolina Campos Mateus, Angélica Fortes Drummond Chicarino Varajão, Fábio Soares De Oliveira, Sabine Petit, Carlos Ernesto Gonçalves Reynaud Schaefer. Geochemical evolution of soils developed from pyroclastic rocks of Trindade Island, South Atlantic. Brazilian journal of geology, In press, 51, 10.1590/2317-4889202120200073. hal-03030558 HAL Id: hal-03030558 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03030558 Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SILEIR RA A D B E E G D E A O D L E O I G C I A O ORIGINAL ARTICLE BJGEO S https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-4889202120200073 Brazilian Journal of Geology D ESDE 1946 Geochemical evolution of soils developed from pyroclastic rocks of Trindade Island, South Atlantic Ana Carolina Campos Mateus1* , Angélica Fortes Drummond Chicarino Varajão1 , Fábio Soares de Oliveira2 , Sabine Petit3 , Carlos Ernesto Gonçalves Reynaud Schaefer4 Abstract The geochemical behavior of the major, minor, trace and rare earths elements (REEs) in soil profiles from ultramafic volcanoclastic rocks of the Vulcão do Paredão and Morro Vermelho Formation from Trindade Island (TI) was analyzed in this study. -

Capítulo 9 Biologia E Conservação Do Petrel-De-Trindade Pterodroma Arminjoniana

Capítulo 9 Biologia e Conservação do Petrel-de-Trindade Pterodroma arminjoniana (Aves: Procellariidae ) na Ilha da Trindade, Atlântico sul, Brasil Giovannini Luigi Leandro Bugoni Francisco Pedro Fonseca-Neto Dante M. Teixeira ILHAS OCEÂNICAS BRASILEIRAS: DA PESQUISA AO MANEJO – VOLUME II [ 223 Resumo O petrel-de-trindade Pterodroma arminjoniana é o único representante do gênero a se repro- duzir no Brasil. Esta ave foi estudada na Ilha da Trindade, Atlântico sul (20 °30’S–29 °19’W), por pesquisadores do Museu Nacional/UFRJ (1988 a 1993), Projeto Tamar/ICMBio (1994 a 2000) e Projeto Albatroz e University of Glasgow (2006 e 2007). Segundo dados obtidos após 25 meses de trabalho de campo, determinou-se que P. arminjoniana apresenta um extenso período de incubação, •lhotes de lento crescimento e freqüência bastante irregular de alimentação das crias. Foi estimado que a colônia do petrel-de-trindade constitui-se de cerca de 1.130 casais e que a reprodução ocorre durante todo o ano. A postura consiste de um único ovo, que é incubado por ambos os sexos ao longo de 52 dias. O •lhote nasce completamente coberto por uma espessa camada de neóptilas e torna-se independente ao redor dos 100 dias de vida. Observou-se •delidade ao ninho, à colônia e ao parceiro. O caranguejo terrestre Gecarcinus la- gostoma é um importante predador de ovos e •lhotes recém-nascidos. Embora P. arminjoniana ainda seja comum em Trindade, sua população pode ter sido afetada pela ocupação humana da ilha, já que parte de seus sítios de nidi•cação teria estado sujeita à ação predatória de porcos e gatos introduzidos no passado. -

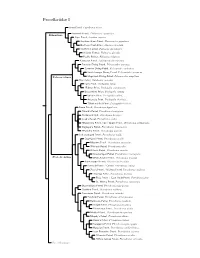

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma