3 ⇥ 3 Matrices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

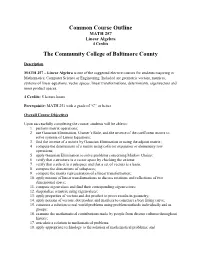

Common Course Outline MATH 257 Linear Algebra 4 Credits

Common Course Outline MATH 257 Linear Algebra 4 Credits The Community College of Baltimore County Description MATH 257 – Linear Algebra is one of the suggested elective courses for students majoring in Mathematics, Computer Science or Engineering. Included are geometric vectors, matrices, systems of linear equations, vector spaces, linear transformations, determinants, eigenvectors and inner product spaces. 4 Credits: 5 lecture hours Prerequisite: MATH 251 with a grade of “C” or better Overall Course Objectives Upon successfully completing the course, students will be able to: 1. perform matrix operations; 2. use Gaussian Elimination, Cramer’s Rule, and the inverse of the coefficient matrix to solve systems of Linear Equations; 3. find the inverse of a matrix by Gaussian Elimination or using the adjoint matrix; 4. compute the determinant of a matrix using cofactor expansion or elementary row operations; 5. apply Gaussian Elimination to solve problems concerning Markov Chains; 6. verify that a structure is a vector space by checking the axioms; 7. verify that a subset is a subspace and that a set of vectors is a basis; 8. compute the dimensions of subspaces; 9. compute the matrix representation of a linear transformation; 10. apply notions of linear transformations to discuss rotations and reflections of two dimensional space; 11. compute eigenvalues and find their corresponding eigenvectors; 12. diagonalize a matrix using eigenvalues; 13. apply properties of vectors and dot product to prove results in geometry; 14. apply notions of vectors, dot product and matrices to construct a best fitting curve; 15. construct a solution to real world problems using problem methods individually and in groups; 16. -

Introduction to Linear Bialgebra

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Mathematics and Statistics Faculty and Staff Publications Academic Department Resources 2005 INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA Florentin Smarandache University of New Mexico, [email protected] W.B. Vasantha Kandasamy K. Ilanthenral Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/math_fsp Part of the Algebra Commons, Analysis Commons, Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics Commons, and the Other Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Smarandache, Florentin; W.B. Vasantha Kandasamy; and K. Ilanthenral. "INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA." (2005). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/math_fsp/232 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Department Resources at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mathematics and Statistics Faculty and Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. INTRODUCTION TO LINEAR BIALGEBRA W. B. Vasantha Kandasamy Department of Mathematics Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Chennai – 600036, India e-mail: [email protected] web: http://mat.iitm.ac.in/~wbv Florentin Smarandache Department of Mathematics University of New Mexico Gallup, NM 87301, USA e-mail: [email protected] K. Ilanthenral Editor, Maths Tiger, Quarterly Journal Flat No.11, Mayura Park, 16, Kazhikundram Main Road, Tharamani, Chennai – 600 113, India e-mail: [email protected] HEXIS Phoenix, Arizona 2005 1 This book can be ordered in a paper bound reprint from: Books on Demand ProQuest Information & Learning (University of Microfilm International) 300 N. -

Lesson 2: the Multiplication of Polynomials

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 2 M1 ALGEBRA II Lesson 2: The Multiplication of Polynomials Student Outcomes . Students develop the distributive property for application to polynomial multiplication. Students connect multiplication of polynomials with multiplication of multi-digit integers. Lesson Notes This lesson begins to address standards A-SSE.A.2 and A-APR.C.4 directly and provides opportunities for students to practice MP.7 and MP.8. The work is scaffolded to allow students to discern patterns in repeated calculations, leading to some general polynomial identities that are explored further in the remaining lessons of this module. As in the last lesson, if students struggle with this lesson, they may need to review concepts covered in previous grades, such as: The connection between area properties and the distributive property: Grade 7, Module 6, Lesson 21. Introduction to the table method of multiplying polynomials: Algebra I, Module 1, Lesson 9. Multiplying polynomials (in the context of quadratics): Algebra I, Module 4, Lessons 1 and 2. Since division is the inverse operation of multiplication, it is important to make sure that your students understand how to multiply polynomials before moving on to division of polynomials in Lesson 3 of this module. In Lesson 3, division is explored using the reverse tabular method, so it is important for students to work through the table diagrams in this lesson to prepare them for the upcoming work. There continues to be a sharp distinction in this curriculum between justification and proof, such as justifying the identity (푎 + 푏)2 = 푎2 + 2푎푏 + 푏 using area properties and proving the identity using the distributive property. -

21. Orthonormal Bases

21. Orthonormal Bases The canonical/standard basis 011 001 001 B C B C B C B0C B1C B0C e1 = B.C ; e2 = B.C ; : : : ; en = B.C B.C B.C B.C @.A @.A @.A 0 0 1 has many useful properties. • Each of the standard basis vectors has unit length: q p T jjeijj = ei ei = ei ei = 1: • The standard basis vectors are orthogonal (in other words, at right angles or perpendicular). T ei ej = ei ej = 0 when i 6= j This is summarized by ( 1 i = j eT e = δ = ; i j ij 0 i 6= j where δij is the Kronecker delta. Notice that the Kronecker delta gives the entries of the identity matrix. Given column vectors v and w, we have seen that the dot product v w is the same as the matrix multiplication vT w. This is the inner product on n T R . We can also form the outer product vw , which gives a square matrix. 1 The outer product on the standard basis vectors is interesting. Set T Π1 = e1e1 011 B C B0C = B.C 1 0 ::: 0 B.C @.A 0 01 0 ::: 01 B C B0 0 ::: 0C = B. .C B. .C @. .A 0 0 ::: 0 . T Πn = enen 001 B C B0C = B.C 0 0 ::: 1 B.C @.A 1 00 0 ::: 01 B C B0 0 ::: 0C = B. .C B. .C @. .A 0 0 ::: 1 In short, Πi is the diagonal square matrix with a 1 in the ith diagonal position and zeros everywhere else. -

Multivector Differentiation and Linear Algebra 0.5Cm 17Th Santaló

Multivector differentiation and Linear Algebra 17th Santalo´ Summer School 2016, Santander Joan Lasenby Signal Processing Group, Engineering Department, Cambridge, UK and Trinity College Cambridge [email protected], www-sigproc.eng.cam.ac.uk/ s jl 23 August 2016 1 / 78 Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. 2 / 78 Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. 3 / 78 Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. 4 / 78 Summary Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... 5 / 78 Overview The Multivector Derivative. Examples of differentiation wrt multivectors. Linear Algebra: matrices and tensors as linear functions mapping between elements of the algebra. Functional Differentiation: very briefly... Summary 6 / 78 We now want to generalise this idea to enable us to find the derivative of F(X), in the A ‘direction’ – where X is a general mixed grade multivector (so F(X) is a general multivector valued function of X). Let us use ∗ to denote taking the scalar part, ie P ∗ Q ≡ hPQi. Then, provided A has same grades as X, it makes sense to define: F(X + tA) − F(X) A ∗ ¶XF(X) = lim t!0 t The Multivector Derivative Recall our definition of the directional derivative in the a direction F(x + ea) − F(x) a·r F(x) = lim e!0 e 7 / 78 Let us use ∗ to denote taking the scalar part, ie P ∗ Q ≡ hPQi. -

Algebra of Linear Transformations and Matrices Math 130 Linear Algebra

Then the two compositions are 0 −1 1 0 0 1 BA = = 1 0 0 −1 1 0 Algebra of linear transformations and 1 0 0 −1 0 −1 AB = = matrices 0 −1 1 0 −1 0 Math 130 Linear Algebra D Joyce, Fall 2013 The products aren't the same. You can perform these on physical objects. Take We've looked at the operations of addition and a book. First rotate it 90◦ then flip it over. Start scalar multiplication on linear transformations and again but flip first then rotate 90◦. The book ends used them to define addition and scalar multipli- up in different orientations. cation on matrices. For a given basis β on V and another basis γ on W , we have an isomorphism Matrix multiplication is associative. Al- γ ' φβ : Hom(V; W ) ! Mm×n of vector spaces which though it's not commutative, it is associative. assigns to a linear transformation T : V ! W its That's because it corresponds to composition of γ standard matrix [T ]β. functions, and that's associative. Given any three We also have matrix multiplication which corre- functions f, g, and h, we'll show (f ◦ g) ◦ h = sponds to composition of linear transformations. If f ◦ (g ◦ h) by showing the two sides have the same A is the standard matrix for a transformation S, values for all x. and B is the standard matrix for a transformation T , then we defined multiplication of matrices so ((f ◦ g) ◦ h)(x) = (f ◦ g)(h(x)) = f(g(h(x))) that the product AB is be the standard matrix for S ◦ T . -

Chapter 2. Multiplication and Division of Whole Numbers in the Last Chapter You Saw That Addition and Subtraction Were Inverse Mathematical Operations

Chapter 2. Multiplication and Division of Whole Numbers In the last chapter you saw that addition and subtraction were inverse mathematical operations. For example, a pay raise of 50 cents an hour is the opposite of a 50 cents an hour pay cut. When you have completed this chapter, you’ll understand that multiplication and division are also inverse math- ematical operations. 2.1 Multiplication with Whole Numbers The Multiplication Table Learning the multiplication table shown below is a basic skill that must be mastered. Do you have to memorize this table? Yes! Can’t you just use a calculator? No! You must know this table by heart to be able to multiply numbers, to do division, and to do algebra. To be blunt, until you memorize this entire table, you won’t be able to progress further than this page. MULTIPLICATION TABLE ϫ 012 345 67 89101112 0 000 000LEARNING 00 000 00 1 012 345 67 89101112 2 024 681012Copy14 16 18 20 22 24 3 036 9121518212427303336 4 0481216 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 5051015202530354045505560 6061218243036424854606672Distribute 7071421283542495663707784 8081624324048566472808896 90918273HAWKESReview645546372819099108 10 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 ©11 0 11 22 33 44NOT 55 66 77 88 99 110 121 132 12 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 84 96 108 120 132 144 Do Let’s get a couple of things out of the way. First, any number times 0 is 0. When we multiply two numbers, we call our answer the product of those two numbers. -

Grade 7/8 Math Circles the Scale of Numbers Introduction

Faculty of Mathematics Centre for Education in Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1 Mathematics and Computing Grade 7/8 Math Circles November 21/22/23, 2017 The Scale of Numbers Introduction Last week we quickly took a look at scientific notation, which is one way we can write down really big numbers. We can also use scientific notation to write very small numbers. 1 × 103 = 1; 000 1 × 102 = 100 1 × 101 = 10 1 × 100 = 1 1 × 10−1 = 0:1 1 × 10−2 = 0:01 1 × 10−3 = 0:001 As you can see above, every time the value of the exponent decreases, the number gets smaller by a factor of 10. This pattern continues even into negative exponent values! Another way of picturing negative exponents is as a division by a positive exponent. 1 10−6 = = 0:000001 106 In this lesson we will be looking at some famous, interesting, or important small numbers, and begin slowly working our way up to the biggest numbers ever used in mathematics! Obviously we can come up with any arbitrary number that is either extremely small or extremely large, but the purpose of this lesson is to only look at numbers with some kind of mathematical or scientific significance. 1 Extremely Small Numbers 1. Zero • Zero or `0' is the number that represents nothingness. It is the number with the smallest magnitude. • Zero only began being used as a number around the year 500. Before this, ancient mathematicians struggled with the concept of `nothing' being `something'. 2. Planck's Constant This is the smallest number that we will be looking at today other than zero. -

Determinants Math 122 Calculus III D Joyce, Fall 2012

Determinants Math 122 Calculus III D Joyce, Fall 2012 What they are. A determinant is a value associated to a square array of numbers, that square array being called a square matrix. For example, here are determinants of a general 2 × 2 matrix and a general 3 × 3 matrix. a b = ad − bc: c d a b c d e f = aei + bfg + cdh − ceg − afh − bdi: g h i The determinant of a matrix A is usually denoted jAj or det (A). You can think of the rows of the determinant as being vectors. For the 3×3 matrix above, the vectors are u = (a; b; c), v = (d; e; f), and w = (g; h; i). Then the determinant is a value associated to n vectors in Rn. There's a general definition for n×n determinants. It's a particular signed sum of products of n entries in the matrix where each product is of one entry in each row and column. The two ways you can choose one entry in each row and column of the 2 × 2 matrix give you the two products ad and bc. There are six ways of chosing one entry in each row and column in a 3 × 3 matrix, and generally, there are n! ways in an n × n matrix. Thus, the determinant of a 4 × 4 matrix is the signed sum of 24, which is 4!, terms. In this general definition, half the terms are taken positively and half negatively. In class, we briefly saw how the signs are determined by permutations. -

28. Exterior Powers

28. Exterior powers 28.1 Desiderata 28.2 Definitions, uniqueness, existence 28.3 Some elementary facts 28.4 Exterior powers Vif of maps 28.5 Exterior powers of free modules 28.6 Determinants revisited 28.7 Minors of matrices 28.8 Uniqueness in the structure theorem 28.9 Cartan's lemma 28.10 Cayley-Hamilton Theorem 28.11 Worked examples While many of the arguments here have analogues for tensor products, it is worthwhile to repeat these arguments with the relevant variations, both for practice, and to be sensitive to the differences. 1. Desiderata Again, we review missing items in our development of linear algebra. We are missing a development of determinants of matrices whose entries may be in commutative rings, rather than fields. We would like an intrinsic definition of determinants of endomorphisms, rather than one that depends upon a choice of coordinates, even if we eventually prove that the determinant is independent of the coordinates. We anticipate that Artin's axiomatization of determinants of matrices should be mirrored in much of what we do here. We want a direct and natural proof of the Cayley-Hamilton theorem. Linear algebra over fields is insufficient, since the introduction of the indeterminate x in the definition of the characteristic polynomial takes us outside the class of vector spaces over fields. We want to give a conceptual proof for the uniqueness part of the structure theorem for finitely-generated modules over principal ideal domains. Multi-linear algebra over fields is surely insufficient for this. 417 418 Exterior powers 2. Definitions, uniqueness, existence Let R be a commutative ring with 1. -

The Notion Of" Unimaginable Numbers" in Computational Number Theory

Beyond Knuth’s notation for “Unimaginable Numbers” within computational number theory Antonino Leonardis1 - Gianfranco d’Atri2 - Fabio Caldarola3 1 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Calabria Arcavacata di Rende, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Calabria Arcavacata di Rende, Italy 3 Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Calabria Arcavacata di Rende, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Literature considers under the name unimaginable numbers any positive in- teger going beyond any physical application, with this being more of a vague description of what we are talking about rather than an actual mathemati- cal definition (it is indeed used in many sources without a proper definition). This simply means that research in this topic must always consider shortened representations, usually involving recursion, to even being able to describe such numbers. One of the most known methodologies to conceive such numbers is using hyper-operations, that is a sequence of binary functions defined recursively starting from the usual chain: addition - multiplication - exponentiation. arXiv:1901.05372v2 [cs.LO] 12 Mar 2019 The most important notations to represent such hyper-operations have been considered by Knuth, Goodstein, Ackermann and Conway as described in this work’s introduction. Within this work we will give an axiomatic setup for this topic, and then try to find on one hand other ways to represent unimaginable numbers, as well as on the other hand applications to computer science, where the algorith- mic nature of representations and the increased computation capabilities of 1 computers give the perfect field to develop further the topic, exploring some possibilities to effectively operate with such big numbers. -

Multiplication Fact Strategies Assessment Directions and Analysis

Multiplication Fact Strategies Wichita Public Schools Curriculum and Instructional Design Mathematics Revised 2014 KCCRS version Table of Contents Introduction Page Research Connections (Strategies) 3 Making Meaning for Operations 7 Assessment 9 Tools 13 Doubles 23 Fives 31 Zeroes and Ones 35 Strategy Focus Review 41 Tens 45 Nines 48 Squared Numbers 54 Strategy Focus Review 59 Double and Double Again 64 Double and One More Set 69 Half and Then Double 74 Strategy Focus Review 80 Related Equations (fact families) 82 Practice and Review 92 Wichita Public Schools 2014 2 Research Connections Where Do Fact Strategies Fit In? Adapted from Randall Charles Fact strategies are considered a crucial second phase in a three-phase program for teaching students basic math facts. The first phase is concept learning. Here, the goal is for students to understand the meanings of multiplication and division. In this phase, students focus on actions (i.e. “groups of”, “equal parts”, “building arrays”) that relate to multiplication and division concepts. An important instructional bridge that is often neglected between concept learning and memorization is the second phase, fact strategies. There are two goals in this phase. First, students need to recognize there are clusters of multiplication and division facts that relate in certain ways. Second, students need to understand those relationships. These lessons are designed to assist with the second phase of this process. If you have students that are not ready, you will need to address the first phase of concept learning. The third phase is memorization of the basic facts. Here the goal is for students to master products and quotients so they can recall them efficiently and accurately, and retain them over time.