Human Genome Project the Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Biosystems 3730 and 3730Xl DNA Analyzers

SPECIFICATION SHEET 3730 and 3730xl DNA Analyzers Applied Biosystems 3730 and 3730xl DNA Analyzers Introduction Applied Biosystems 3730 & 3730xl DNA Analyzers were developed to meet the growing needs of institutions ranging from core and research labs in academia, government, and medicine to biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and genome centers. These high-throughput instruments couple advances in automation and optics with proprietary Applied Biosystems reagents and software to support a diverse range Key Features Key Benefits of genetic analysis projects. By • Dual-side capillary illumination • Highest-quality DNA sequencing data dramatically improving data quality, at lowest cost • Backside-thinned CCD significantly reducing total cost per – POP-7™ Polymer separation matrix sample, and enabling more runs per • Integrated auto-sampler and sample increases read length and reduces day, 3730/3730xl DNA Analyzers make plate stacker run time it quicker and easier for investigators • Onboard piercing station to get meaningful results in evolving – Multiple run modules provide options genomic applications. Whether your • Internal barcode reader for targeted length of read lab is involved in de novo sequencing, • Onboard polymer for up to 100 runs – High optical sensitivity reduces DNA resequencing, microsatellite-based and reagent consumption fragment analysis, or SNP genotyping, • Automated basecalling and quality 3730/3730xl DNA Analyzers are the value assignment – In-capillary detection consumes ideal platform for better, faster, cheaper • -

Automated DNA Sequencing

Automated DNA Sequencing Chemistry Guide ©Copyright 1998, The Perkin-Elmer Corporation This product is for research purposes only. ABI PRISM, MicroAmp, and Perkin-Elmer are registered trademarks of The Perkin-Elmer Corporation. ABI, ABI PRISM, Applied Biosystems, BigDye, CATALYST, PE, PE Applied Biosystems, POP, POP-4, POP-6, and Primer Express are trademarks of The Perkin-Elmer Corporation. AmpliTaq, AmpliTaq Gold, and GeneAmp are registered trademarks of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. Centricon is a registered trademark of W. R. Grace and Co. Centri-Sep is a trademark of Princeton Separations, Inc. Long Ranger is a trademark of The FMC Corporation. Macintosh and Power Macintosh are registered trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. pGEM is a registered trademark of Promega Corporation. Contents 1 Introduction. 1-1 New DNA Sequencing Chemistry Guide . 1-1 Introduction to Automated DNA Sequencing . 1-2 ABI PRISM Sequencing Chemistries . 1-5 PE Applied Biosystems DNA Sequencing Instruments . 1-7 Data Collection and Analysis Settings . 1-12 2 ABI PRISM DNA Sequencing Chemistries . 2-1 Overview . 2-1 Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kits . 2-2 Dye Primer Cycle Sequencing Kits . 2-8 Dye Spectra . 2-12 Chemistry/Instrument/Filter Set Compatibilities . 2-13 Dye/Base Relationships for Sequencing Chemistries . 2-14 Choosing a Sequencing Chemistry. 2-15 3 Performing DNA Sequencing Reactions . 3-1 Overview . 3-1 DNA Template Preparation . 3-2 Sequencing PCR Templates . 3-10 DNA Template Quality. 3-15 DNA Template Quantity. 3-17 Primer Design and Quantitation . 3-18 Reagent and Equipment Considerations. 3-20 Preparing Cycle Sequencing Reactions . 3-21 Cycle Sequencing . 3-27 Preparing Extension Products for Electrophoresis . -

Document Title: Development and Evaluation of a Whole Genome Amplification Method for Accurate Multiplex STR Genotyping of Compromised Forensic Casework Samples

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Development and Evaluation of a Whole Genome Amplification Method for Accurate Multiplex STR Genotyping of Compromised Forensic Casework Samples Author: Tracey Dawson Cruz, Ph.D. Document No.: 227501 Date Received: July 2009 Award Number: 2005-DA-BX-K002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT Development and Evaluation of a Whole Genome Amplification Method for Accurate Multiplex STR Genotyping of Compromised Forensic Casework Samples NIJ Award #: 2005-DA-BX-K002 Author: Tracey Dawson Cruz 1 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

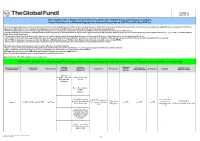

List of SARS-Cov-2 Diagnostic Test Kits and Equipments Eligible For

Version 33 2021-09-24 List of SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic test kits and equipments eligible for procurement according to Board Decision on Additional Support for Country Responses to COVID-19 (GF/B42/EDP11) The following emergency procedures established by WHO and the Regulatory Authorities of the Founding Members of the GHTF have been identified by the QA Team and will be used to determine eligibility for procurement of COVID-19 diagnostics. The product, to be considered as eligible for procurement with GF resources, shall be listed in one of the below mentioned lists: - WHO Prequalification decisions made as per the Emergency Use Listing (EUL) procedure opened to candidate in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) to detect SARS-CoV-2; - The United States Food and Drug Administration’s (USFDA) general recommendations and procedures applicable to the authorization of the emergency use of certain medical products under sections 564, 564A, and 564B of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act; - The decisions taken based on the Canada’s Minister of Health interim order (IO) to expedite the review of these medical devices, including test kits used to diagnose COVID-19; - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) for inclusion on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on the basis of the Expedited TGA assessment - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare after March 2020 with prior scientific review by the PMDA - The COVID-19 diagnostic tests listed on the French -

Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory Taqpath SARS-Cov-2 Assay EUA Summary

Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay EUA Summary ACCELERATED EMERGENCY USE AUTHORIZATION (EUA) SUMMARY SARS-CoV-2 ASSAY (Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory) For in vitro diagnostic use Rx only For use under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) Only (The Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay will be performed in the Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory, a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a certified high-complexity laboratory, per the Instructions for Use that were reviewed by the FDA under this EUA). INTENDED USE The Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory TaqPath SARS-CoV-2 Assay is a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test intended for the qualitative detection of nucleic acid from SARS-CoV-2 in oropharyngeal (throat) swab, nasopharyngeal swab, anterior nasal swab, mid-turbinate nasal swab, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from individuals suspected of COVID-19 by their healthcare provider. This test is also for use with saliva specimens that are self-collected at home or in a healthcare setting by individuals using the Spectrum Solutions LLC SDNA-1000 Saliva Collection Device when determined to be appropriate by a healthcare provider. Testing is limited to Rutgers Clinical Genomics Laboratory (RCGL) at RUCDR Infinite Biologics – Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ, that is a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA), 42 U.S.C. §263a certified high-complexity laboratory. Results are for the detection and identification of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. The SARS- CoV-2 RNA is generally detectable in respiratory specimens during the acute phase of infection. -

DNA Fragment Analysis by Capillary Electrophoresis User Guide

USER GUIDE DNA Fragment Analysis by Capillary Electrophoresis Publication Number 4474504 Revision B For Research Use Only. Not intended for use in diagnostic procedures. For Research Use Only. Not intended for use in diagnostic procedures. The information in this guide is subject to change without notice. DISCLAIMER LIFE TECHNOLOGIES CORPORATION AND/OR ITS AFFILIATE(S) DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES WITH RESPECT TO THIS DOCUMENT, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR NON-INFRINGEMENT. TO THE EXTENT ALLOWED BY LAW, IN NO EVENT SHALL LIFE TECHNOLOGIES AND/OR ITS AFFILIATE(S) BE LIABLE, WHETHER IN CONTRACT, TORT, WARRANTY, OR UNDER ANY STATUTE OR ON ANY OTHER BASIS FOR SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, INDIRECT, PUNITIVE, MULTIPLE OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES IN CONNECTION WITH OR ARISING FROM THIS DOCUMENT, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE USE THEREOF. TRADEMARKS All trademarks are the property of Thermo Fisher Scientific and its subsidiaries unless otherwise specified. AmpErase, AmpliTaq, AmpliTaq Gold, and TaqMan are registered trademarks of Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. AFLP is a registered trademark of Keygene N.V. Millipore is a registered trademark of Merck KGaA. © 2014 Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. All rights reserved. Contents About This Guide . 13 Revision history . 13 Purpose . 13 Prerequisites . 13 Structure of this guide . 14 ■ CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Fragment Analysis . 15 Fragment analysis versus sequencing…what is the difference? . 15 Fragment analysis . 15 Sequencing . 16 What can I do with fragment analysis? . 16 Types of applications . 16 Applications described in this guide . 17 What is capillary electrophoresis? . 18 Fragment analysis workflow . 19 ■ CHAPTER 2 Experimental Design . -

Supporting Information Supplementary Methods

Supporting Information Supplementary methods This appendix was part of the submitted manuscript and has been peer reviewed. It is posted as supplied by the authors. Appendix to: Caly L, Druce J, Roberts J, et al. Isolation and rapid sharing of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SAR-CoV-2) from the first patient diagnosed with COVID-19 in Australia. Med J Aust 2020; doi: 10.5694/mja2.50569. Supplementary methods 1.1 Generation of SARS-CoV-2 cDNA 200μL aliquots from swab (nasopharyngeal in VTM), sputum, urine, faeces and serum samples were subjected to RNA extraction using the QIAamp 96 Virus QIAcube HT Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and eluted in 60μL. Reverse transcription was performed using the BioLine SensiFAST cDNA kit (Bioline, London, United Kingdom), total reaction mixture (20μL), containing 10μL RNA extract, 4μL 5x TransAmp buffer, 1μL reverse transcriptase and 5μL nuclease-free water. The reactions were incubated at 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 15 min and 85°C for 5 min. 1.2 Nested SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing A PCR mixture containing 2μL cDNA, 1.6 μl 25mM MgCl2, 4μL 10x Qiagen Taq Buffer, 0.4μL 20mM dNTPs, 0.3μL Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and 2μL of 10 μM primer pools as described2. Briefly, first round included the forward (5'-GGKTGGGAYTAYCCKAARTG-3') and reverse (5'-GGKTGGGAYTAYCCKAARTG-3') primers. Cycling conditions were 94°C for 10min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 48°C for 30s and 72°C for 40s, with a final extension of 72°C for 10 min. -

Applied Biosystems 3130 and 3130Xl Genetic Analyzers

System Profile Applied Biosystems 3130 and 3130xl Genetic Analyzers. System Profile Applied Biosystems 3130 and 3130xl Genetic Analyzers Table of Contents A Powerful Blend of Flexibility and Performance 1 Ease-of-Use 1 Key Features 2 Capillary Electrophoresis 2 Automated Polymer Delivery System 2 Enhanced Thermal Control 2 High-Perfomance Capillaries and Electro-osmotic Flow Suppression (EOF) Polymers 2 Detection Method Designed for Sensitivity 3 Spectral Array Detection 3 Application Flexibility 4 Complete System Optimized for Multiple Applications 4 One Polymer, One Array, Maximum Performance 4 System Software Suite 5 Results 6 Summary 9 References 10 www.appliedbiosystems.com 16-capillary 3130xl Genetic Analyzer: High-performance workhorse. With 16-capillary throughput and advanced automation capabilities, the 3130xl system is flexible enough to meet the throughput needs of the busiest core facility or research group. The streamlined set-up and 24-hour unattended operation make it an ideal choice for low or medium throughput laboratories. Ease-of-Use Complete automation. At every scale, Applied Biosystems genetic analyzers are known for their advanced automation and “hands-free” operation. The Automated Polymer Delivery System A Powerful Blend of Flexibility and Performance eliminates manual washing and filling of polymer syringes, Applied Biosystems has a long tradition of providing significantly reducing the time required for instrument set- excellence in life science instruments, reagents, and software. up and maintenance. All steps are automated, including This tradition of pioneering and innovation in the field polymer loading, sample injection, separation and detection, of genetic analysis continues with the introduction of and data analysis. After placing plates on the autosampler Applied Biosystems next-generation systems, the 3130 and importing sample information, just select the “Start and 3130xl Genetic Analyzers. -

In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE NEW ORLEANS EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM, on behalf of itself and all other similarly situated shareholders of Celera Corporation, Plaintiff, v. C.A. No. _________ RICHARD H. AYERS, JEAN-LUC BELINGARD, WILLIAM G. GREEN, PETER BARTON HUTT, GAIL K. NAUGHTON, KATHY ORDONEZ, WAYNE I. ROE, BENNETT M. SHAPIRO, CELERA CORPORATION, QUEST DIAGNOSTICS INCORPORATED, AND SPARK ACQUISITION CORPORATION, Defendants. VERIFIED CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, New Orleans Employees’ Retirement System (“NOERS” or “Plaintiff”), on behalf of itself and all other similarly situated public shareholders of Celera Corporation (hereafter, “Celera” or the “Company”), brings the following Verified Class Action Complaint (the “Complaint”) against the members of the board of directors of Celera (the “Celera Board” or “Board”) for breaching their fiduciary duties, and against Quest Diagnostics Incorporated (“Quest”) and Spark Acquisition Corporation (“Spark”) for aiding and abetting the same. The allegations of the Complaint are based on the knowledge of Plaintiff as to itself, and on information and belief, including the investigation of counsel and review of publicly available information as to all other matters. INTRODUCTION 1. This is a case about a corporate board that chose to negotiate an all-cash sale of the company while operating under the same material conflict of interest that lay at the heart of the Delaware Supreme Court’s ruling in Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes, Inc., 506 A.2d 173 (Del. 1986). Over the weeks leading to this action, the Celera Board faced a clear choice: disclose a material accounting fraud and risk liability that would flow from that disclosure, or negotiate a desperate and rushed sale of the company at whatever price a potential bidder would offer in order to insulate themselves from liability and secure their own financial well-being. -

Preliminary Healthcare Agenda 01.03X

29th Annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference January 10 - 13, 2011 Westin St. Francis Hotel, San Francisco, CA Preliminary Conference Agenda SUNDAY, JANUARY 9 - Registration in Tower Salon A - 3 to 9 PM MONDAY, JANUARY 10 - Registration in Tower Salon A - 6:45 AM, Breakfast in Italian Foyer Grand Ballroom Colonial Room California West California East Elizabethan A/B Elizabethan C/D Alexandra's Breakout: Borgia Room Breakout: Georgian Room Breakout: Olympic Room Breakout: Yorkshire Room Breakout: Sussex Room Private Company Track Not-for-Profit Track 7:30 AM Opening Remarks: Doug Braunstein - Chief Financial Officer, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Grand Ballroom Astra Tech 8:00 AM Celgene Corporation Kinetic Concepts, Inc Alkermes, Inc. Biocon Limited Catalent (private company) 8:30 AM Express Scripts Inc. Agilent Technologies Inc. Beckman Coulter Inc. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. Quality Systems Axcan Intermediate Holdings 9:00 AM Roche Holding AG Zimmer Holdings, Inc. Genoptix, Inc. ImmunoGen, Inc Health Net Inc. Merrimack Pharmaceuticals Inc. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Allscripts Healthcare Solutions, 9:30 AM Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. Lonza Group Ltd Henry Schein Inc. Surgical Care Affiliates Incorporated Inc. 10:00 AM Medtronic, Inc. WellPoint, Inc. Onyx Pharmaceuticals Inc. Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Align Technology Inc.* Symphogen 10:30 AM Room Not Available Medco Health Solutions, Inc. Smith & Nephew plc* Medivation, Inc. Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Zeltiq Aesthetics 11:00 AM Room Not Available Merck KGaA Perrigo Company Healthways Incorporated BioMimetic Therapeutics, Inc. Penumbra, Inc. 11:30 AM Room Not Available Dendreon Corporation Gen-Probe Inc. Select Medical Corporation ArthroCare Corporation PTC Therapeutics, Inc. 12:00 PM Luncheon & Keynote: Nancy-Ann DeParle - Counselor to the President and Director of the White House Office of Health Reform, Grand Ballroom Endo Pharmaceuticals Holdings 1:30 PM Room Not Available Amylin Pharmaceuticals Inc. -

Celera CORP Form 10-KT Filed 2009-03-25

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-KT Transition report pursuant to Rule 13a-10 or 15d-10 Filing Date: 2009-03-25 | Period of Report: 2008-12-27 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-09-063099 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER Celera CORP Mailing Address Business Address 1401 HARBOR BAY 1401 HARBOR BAY CIK:1428156| IRS No.: 262028576 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 PARKWAY PARKWAY Type: 10-KT | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-34116 | Film No.: 09704683 ALAMEDA CA 94502 ALAMEDA CA 94502 SIC: 8731 Commercial physical & biological research 510-749-4200 Copyright © 2014 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-KT ¨ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED x TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM JULY 1, 2008 TO DECEMBER 27, 2008 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER: 001-34116 Celera Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 26-2028576 (State or other jurisdiction (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) Identification No.) 1401 Harbor Bay Parkway Alameda, CA 94502 (Address of principal executive offices, with zip code) (510) 749-4200 (Registrants telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of Each Exchange on Which Title of Each Class Registered Common Stock, $.01 par value The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection and Identity of Extraneous Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV)

VIRPRO0118.05 Page 1 of 13 United States Department of Agriculture Center for Veterinary Biologics Testing Protocol Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection and Identity of Extraneous Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV) Date: September 25, 2014 Number: VIRPRO0118.05 Supersedes: VIRPRO0118.04, June 28, 2011 Contact: Sandra K. Conrad, (515) 337-7200 Danielle M. Koski Approvals: /s/Geetha B. Srinivas Date: 13Nov14 Geetha B. Srinivas, Section Leader Virology /s/Rebecca L.W. Hyde Date: 18Nov14 Rebecca L.W. Hyde, Section Leader Quality Management Center for Veterinary Biologics United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service P. O. Box 844 Ames, IA 50010 Mention of trademark or proprietary product does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by USDA and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products that may be suitable. UNCONTROLLED COPY Center for Veterinary Biologics VIRPRO0118.05 Testing Protocol Page 2 of 13 Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection and Identity of Extraneous Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV) Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Materials 2.1 Equipment/instrumentation 2.2 Reagents/supplies 3. Preparation for the Test 3.1 Personnel qualifications/training 3.2 Preparation of equipment/instrumentation 3.3 Preparation of reagents/control procedures 3.4 Storage of the sample 4. Performance of the Test 4.1 DNA extraction 4.2 Amplification of CAV DNA 4.3 Analysis of amplified CAV DNA 5. Interpretation of the Test Results 6. Report of Test Results 7. Summary of Revisions UNCONTROLLED COPY Center for Veterinary Biologics VIRPRO0118.05 Testing Protocol Page 3 of 13 Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Detection and Identity of Extraneous Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV) 1.