Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

A Selected List of Sources for Afro-American Genealogical Research

".'^7,-e....." DOCUMENT RESUME ED 326 461 SO 030 060 AUTHOR Lawson, Sandra M., Comp. TITLE Generations Past: A Selected List of Sources for Afro-American Genealogical Research. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. General Read:ng Rooms Div. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0604-X PUB DATE 88 NOTE 108p. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bi))liographies (131) EDRS PRICE 11F01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *African History; Annotated Bibliographies; *Black History; *Blacks; *Black Studies; *Genealogy; Higher Education; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Afro American Genealogy ABSTRACT Genealogy is the study of the descent of a family from an ancestor or ancestors. This selected list of books in the collections of the Library of Congress was compiled primarily for -esearchers of Afro-American lineages. The bibliography includes guidebooks, bibliographies, genealogies, collective biographies, U.S. local histories, directories, and other works pertaining specifically to Afro-Americans. The sources are listed geographically with citations to histories of Afro-Americans in U.S. cities, towns, counties, and states. Printed family histories and genealogies are major sources for this research, and 56 references by specific family names are included. (NL) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. GENERATIONS PAST c.'lectc(1 bst I)/ Noloco .1(n. Afro-Amok-an (.;olcalo,twal Roca)ch U S OEPARMENT OF EOUCATION 7-, ar ve,1 ES INFORMATION FF. NtiAni( tAer as vgan.Z.1110P 4 A olprove gt tv we^ ev. ,OS s' at +d tp,SOCCLI nel essarav ,ep sent)11,0a1 Of r ''';s*-V Cr; t GENERATIONS PAST A Selected List of Sources for Afro-American Geneah)gical Research Compiled by Sandra M. -

Omaha, Nebraska, Experienced Urban Uprisings the Safeway and Skaggs in 1966, 1968, and 1969

Nebraska National Guardsmen confront protestors at 24th and Maple Streets in Omaha, July 5, 1966. NSHS RG2467-23 82 • NEBRASKA history THEN THE BURNINGS BEGAN Omaha’s Urban Revolts and the Meaning of Political Violence BY ASHLEY M. HOWARD S UMMER 2017 • 83 “ The Negro in the Midwest feels injustice and discrimination no 1 less painfully because he is a thousand miles from Harlem.” DAVID L. LAWRENCE Introduction National in scope, the commission’s findings n August 2014 many Americans were alarmed offered a groundbreaking mea culpa—albeit one by scenes of fire and destruction following the that reiterated what many black citizens already Ideath of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. knew: despite progressive federal initiatives and Despite the prevalence of violence in American local agitation, long-standing injustices remained history, the protest in this Midwestern suburb numerous and present in every black community. took many by surprise. Several factors had rocked In the aftermath of the Ferguson uprisings, news Americans into a naïve slumber, including the outlets, researchers, and the Justice Department election of the country’s first black president, a arrived at a similar conclusion: Our nation has seemingly genial “don’t-rock-the-boat” Midwestern continued to move towards “two societies, one attitude, and a deep belief that racism was long black, one white—separate and unequal.”3 over. The Ferguson uprising shook many citizens, To understand the complexity of urban white and black, wide awake. uprisings, both then and now, careful attention Nearly fifty years prior, while the streets of must be paid to local incidents and their root Detroit’s black enclave still glowed red from five causes. -

![[LB67 LB226 LB434 LB516 LB656 LB658] the Committee on Judiciary](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5838/lb67-lb226-lb434-lb516-lb656-lb658-the-committee-on-judiciary-115838.webp)

[LB67 LB226 LB434 LB516 LB656 LB658] the Committee on Judiciary

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Judiciary Committee March 09, 2017 [LB67 LB226 LB434 LB516 LB656 LB658] The Committee on Judiciary met at 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 9, 2017, in Room 1113 of the State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, for the purpose of conducting a public hearing on LB67, LB434, LB226, LB658, LB516, and LB656. Senators present: Laura Ebke, Chairperson; Patty Pansing Brooks, Vice Chairperson; Roy Baker; Ernie Chambers; Steve Halloran; Matt Hansen; Bob Krist; and Adam Morfeld. Senators absent: None. SENATOR EBKE: Good afternoon. Okay, we're going to get started here. Welcome to the Judiciary Committee. My name is Laura Ebke. I'm from Crete. I represent Legislative District 32 and I'm the Chair of the committee. I would like at this point for my colleagues to introduce themselves, starting with Senator Baker. SENATOR BAKER: I'm Senator Roy Baker. I'm from Norris. I represent District 30 which is Gage County, southern Lancaster County, and a little bit of south Lincoln. SENATOR KRIST: Bob Krist, District 10, Omaha, some Douglas County parts, and also Bennington. SENATOR CHAMBERS: Ernie Chambers, District 11, and I'll be back. SENATOR HALLORAN: Steve Halloran, District 33 which is Adams County, southern and western Hall County. SENATOR EBKE: And very shortly we should be joined by Senator Morfeld from Lincoln, Senator Hansen, who will be sitting next to Senator Halloran, from Lincoln, and Senator Pansing Brooks who serves as the Vice Chair of the committee. And she will be taking the helm from me for a little while, while I have a committee hearing on one of my own bills in another committee shortly. -

The Color Line in Ohio Public Schools, 1829-1890

THE COLOR LINE IN OHIO PUBLIC SCHOOLS, 1829-1890 DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By LEONARD ERNEST ERICKSON, B. A., M. A, ****** The Ohio State University I359 Approved Adviser College of Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is not the work of the author alone, of course, but represents the contributions of many persons. While it is impossible perhaps to mention every one who has helped, certain officials and other persons are especially prominent in my memory for their encouragement and assistance during the course of my research. I would like to express my appreciation for the aid I have received from the clerks of the school boards at Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Warren, and from the Superintendent of Schools at Athens. In a similar manner I am indebted for the courtesies extended to me by the librarians at the Western Reserve Historical Society, the Ohio State Library, the Ohio Supreme Court Library, Wilberforce University, and Drake University. I am especially grateful to certain librarians for the patience and literally hours of service, even beyond the high level customary in that profession. They are Mr. Russell Dozer of the Ohio State University; Mrs. Alice P. Hook of the Historical and Philosophical Society; and Mrs. Elizabeth R. Martin, Miss Prances Goudy, Mrs, Marion Bates, and Mr. George Kirk of the Ohio Historical Society. ii Ill Much of the time for the research Involved In this study was made possible by a very generous fellowship granted for the year 1956 -1 9 5 7, for which I am Indebted to the Graduate School of the Ohio State University. -

Disparate Treatment Analysis

The Diocese of Southern Ohio in Partnership with the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity – The Ohio State University The Bishop’s Task Force on Racial Profiling Volume 2 – Disparate Treatment Analysis Citizenship and Racial Profiling Merelyn Bates-Mims, PhD – Principal Investigator Sharon Davies, JD – Principal Investigator Campuses Eric Abercrumbie, PhD; Prince Brown, PhD; Gary Boyle, PPC; Charles O. Dillard, MD; William B. Lawson, MD, PhD; Brandon Abdullah Powell, BFA; Thomas Rudd, MS; Melvin C. Washington, PhD; Tyrone Williams, PhD Unjust law is no law at all. Where there is no law, neither is there violation. A Research Project – March 2014 PRELUDE Black English: A fair shake in judicial systems? By Merelyn B. Bates-Mims. PUBLISHED 2013-02-09 The Cincinnati Herald Because I had long ‘been away’ to big Washington DC, on my return I obligatorily followed Louisiana custom for courteous visitation to all the homes making up Back o’ the Field, the Bates-Johnson ‘extended family’ neighborhood. As we entered his home, I said to Mr. Amos, my mother’s neighbor and old family friend, “Hi, I haven’t seen you for a long while.” His response:“Sho have! Sho have!” nodding his head in “yes” agreement. Though I have recounted this incident a number of times, its impact on me has never faded. Why? Because I had unknowingly and inadvertently discovered in his response a ‘fossil’, which linguists call a “residual vestige” of a proto form of ancient language. In this case, African language. At the time of his “agreement,” however, I dismissed his reply thinking that he, Mr. -

Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files

City of Cincinnati Municipal Reference Library US-04-09 Vertical Files File Cabinet 1 Drawer 1 1. A3MC Proposed Merger Cincinnati Enquirer and Post 1977 and 1978 2. No Folder Name 3. A33 Cincinnati Post 4. A33 Cincinnati Enquirer 5. A33 Sale of the Enquirer 6. A33 Cincinnati Kurier 7. A33 Newspapers and Magazines 8. Navy 9. A34 Copying, Processes, Printing, Mimeographing, Microfilming 10. A34C Carts, Codes Cincinnati 11. A45Mc General Public Reports (Cincinnati City Bulletin Progress) 12. A49Mc Name- Cincinnati’s “Cincinnati and Queen City of the West 2” 13. Cincinnati- Nourished and Protected by the River that Gave It by William H. Hessler 14. Cincinnati-Name-Flower-Flag-Seal-Key-Songs 15. A49so Ohio 16. Last Edition Printed by the Cincinnati Time-Star July 19, 1958 17. Ohio Sesquicentennial Celebration 18. A6 O/Ohio History-Historical Societies 19. A6mc General Information (I) Cincinnati 20. General Information 2 Cincinnati 21. Cincinnati Geological Society 22. Cincinnati’s Birthdays 23. Pictures of Old Cincinnati 24. A6mc Historical Society- Cincinnati 25. A6mc Famous Cincinnati Families (Enquirer Series 1980) 26. A6mc President Reagan’s Visit to Cincinnati 12/11/81 27. A6mc Pres. Fords Visit to Cincinnati July 1975 and October 28, 1976 28. A6c Famous People Who have Visited Cincinnati 29. A Brief Sketch of the History of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce 30. Cincinnati History 31. History of Cincinnati 1950? 32. Cincinnati 1924 33. Cincinnati 1926 34. Cincinnati 1928 35. Cincinnati 1930 36. Cincinnati 1931 37. Cincinnati 1931 38. Cincinnati 1932 39. Cincinnati 1932 40. Cincinnati 1933 41. Cincinnati 1935 42. -

On the Front Lines for Racial Equality

WWCREIGHTONINDOWINDOW UNIVERSITY ■ WINTER 1995-96 FatherFather Markoe:Markoe: Our ‘Champagne A Life Glass’ Economy on the Don’t Play TV Front Lines Trivia With Her for Racial Finding God in Equality Your Daily Life LETTERS WINDOW Magazine edits Letters to the INDOW Editor, primarily to conform to space W■ ■ limitations. Personally signed letters Volume 12/Number 2 Creighton University Winter 1995-96 are given preference for publication. Our FAX number is: (402) 280-2549. E-Mail to: [email protected] Fr. Markoe’s Battle Against Racism ‘And If the Rules Change?’ Bob Reilly tells you about a man who I have read with interest the article “The was a lifelong fighter. Fr. Markoe Social Roots of Our Environmental found a cause for his fighting ener- Predicament” by Dr. Harper in your Fall gy. The word portrait of a strong- 1995 issue of WINDOW. minded Jesuit begins on Page 3. I would like to pose a question for Dr. Harper. In this third human environmental The Rich Get Richer, revolution, supposing we were to discov- er an inexhaustible source of energy. I The Poor Get Poorer am assuming that the laws of supply and Gerard Stockhausen, S.J., talks about what he calls “our cham- demand would eventually lead it to be at pagne-glass economy.” In this case, it doesn’t mean champagne an inconsequential cost. for everyone; it means the shape of our economy that puts the What would that do to the human liv- rich at the broad top of the glass and the poor at the narrow ing conditions in the world? bottom. -

Who Rules Cincinnati?

Who Rules Cincinnati? A Study of Cincinnati’s Economic Power Structure And its Impact on Communities and People By Dan La Botz Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Published by Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Copyright ©2008 by Dan La Botz Table of Contents Summary......................................................................................................... 1 Preface.............................................................................................................4 Introduction.................................................................................................... 7 Part I - Corporate Power in Cincinnati.........................................................15 Part II - Corporate Power in the Media and Politics.....................................44 Part III - Corporate Power, Social Classes, and Communities......................55 Part IV - Cincinnati: One Hundred Years of Corporate Power.....................69 Discussion..................................................................................................... 85 Bibliography.................................................................................................. 91 Acknowledgments.........................................................................................96 About the Author...........................................................................................97 Summary This investigation into Cincinnati’s power structure finds that a handful of national and multinational corporations dominate -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Marguerita Le Etta Washington

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Marguerita Le Etta Washington Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Washington, Marguerita LeEtta Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Marguerita Le Etta Washington, Dates: October 5, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 5 Betacame SP videocasettes (1:59:27). Description: Abstract: Newspaper publishing chief executive Marguerita Le Etta Washington (1948 - ) was the publisher of the Omaha Star, the only African American newspaper in Nebraska. Washington was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on October 5, 2007, in Omaha, Nebraska. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_280 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Omaha Star publisher Marguerita Le Etta Washington was born on August 16, 1948 to Anna Le Brown and attorney Edmund Duke Washington. Washington’s maternal great grandfather, the richest man in Bessemer, Alabama, left his fortune to his black daughter, her grandmother. The white relatives resolved the matter by burning down the Bessemer courthouse. Washington’s aunt, Mildred Brown, founded Omaha, Nebraska’s Omaha Star in 1938. Washington graduated from Kansas’ Lincoln High School in 1964, at the age of sixteen. Afterwards, she briefly attended Lincoln University in Jefferson City. She then went on to attend the University of Nebraska at Omaha where she earned her B.A. degree in sociology and elementary education. While earning her M.A. degree in administration and special education, Washington began teaching in the Omaha public schools. -

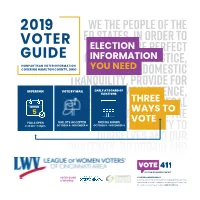

2019 Voter Guide

2019 VOTER ELECTION GUIDE INFORMATION NONPARTISAN VOTER INFORMATION COVERING HAMILTON COUNTY, OHIO YOU NEED IN PERSON VOTE BY MAIL EARLY AT BOARD OF ELECTIONS THREE NOVEMBER 5 WAYS TO POLLS OPEN BALLOTS ACCEPTED SPECIAL HOURS VOTE 6:30 am-7:30pm OCTOBER 8- NOVEMBER 4 OCTOBER 8 - NOVEMBER 4 VOTER GUIDE YOUR PERSONALIZED BALLOT SPONSORS: As well as extended Voter Information including additional questions and information from the candidates and polling place locator, can be found on our voter guide website: www.VOTE411.org About This Guide Featured In This Guide This guide for voters was prepared by the League of Women Voters of the Cincinnati Area Who Am I Voting For? (LWVCA) to provide a forum for candidates and information on the ballot issues. Hamilton Co. Municipal Court Judges .......................................................................... 03 The candidate materials in this guide were assembled in the following manner: Hamilton Co. Educational Service School Board .......................................................... 06 The information for the Hamilton County candidates was solicited and compiled by the League of City of Cincinnati School Board ................................................................................... 06 Women Voters of the Cincinnati Area (LWVCA). LWVCA used the following criteria: The questions selected by LWVCA were advertised to the candidates, who were informed that each response would be printed as received and that all candidates would be solely responsible for the content What Ballot -

Our City Our Culture

OUR CITY OUR CULTURE WRITTEN BY BRANDON VOGEL ILLUSTRATED BY WANDA EWING PRODUCED BY JOHN-PAUL GURNETT OUR CITY, OUR CULTURE Directed by: Emily Brush Edited by: Dr. Jared Leighton Historical Consultant: Dr. Patrick Jones Special Thanks to Harris Payne and Barry Thomas Making Invisible Histories Visible is an initiative of the Omaha Public Schools. i “Our City, Our Culture” was made possible by the Omaha Public Schools, Making Invisible Histories Visible, and The Great Plains Black History Museum. We would also like to thank the University of Nebraska-Lincoln History Department’s History Harvest, The Omaha Visitor’s Center, Iowa Public Television, Tegwin Turner for her photos, and Warren Taylor for taking time to share his wealth of knowledge. ii RATIONALE iii iv iBook Navigation Guide To navigate the iBook: Swipe the page right to left, just like you would turn the pages of a physical book. To go back a page, swipe the page left to right. Widgets There are different kinds of widgets in each iBook. Widgets include pictures, image galleries, videos, interactive images, and more. The widgets vary between iBooks. Below is information on how to navigate some of the basic widgets. Image and Video Widgets Many images can be tapped to view them in full-screen mode. Images viewed in full screen mode can be viewed vertically or horizontally. Some images may have a pop- over feature; a small box with information about the picture will pop up when the image is tapped. Other images may be in a section with scrolling capability. Slide a finger up or down the scroll bar to navigate it.