A Semiotic Analysis of Symphonic Works by William Grant Still, William Levi Dawson, and Florence B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Modulation —

— On Modulation — Dean W. Billmeyer University of Minnesota American Guild of Organists National Convention June 25, 2008 Some Definitions • “…modulating [is] going smoothly from one key to another….”1 • “Modulation is the process by which a change of tonality is made in a smooth and convincing way.”2 • “In tonal music, a firmly established change of key, as opposed to a passing reference to another key, known as a ‘tonicization’. The scale or pitch collection and characteristic harmonic progressions of the new key must be present, and there will usually be at least one cadence to the new tonic.”3 Some Considerations • “Smoothness” is not necessarily a requirement for a successful modulation, as much tonal literature will illustrate. A “convincing way” is a better criterion to consider. • A clear establishment of the new key is important, and usually a duration to the modulation of some length is required for this. • Understanding a modulation depends on the aural perception of the listener; hence, some ambiguity is inherent in distinguishing among a mere tonicization, a “false” modulation, and a modulation. • A modulation to a “foreign” key may be easier to accomplish than one to a diatonically related key: the ear is forced to interpret a new key quickly when there is a large change in the number of accidentals (i.e., the set of pitch classes) in the keys used. 1 Max Miller, “A First Step in Keyboard Modulation”, The American Organist, October 1982. 2 Charles S. Brown, CAGO Study Guide, 1981. 3 Janna Saslaw: “Modulation”, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 5 May 2008), http://www.grovemusic.com. -

557541Bk Kelemen 3+3 4/8/09 2:55 PM Page 1

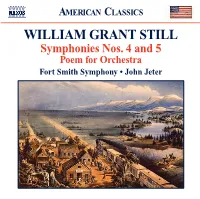

559603bk Still:557541bk Kelemen 3+3 4/8/09 2:55 PM Page 1 John Jeter Fort Smith Symphony John Jeter (‘Jetter’) has been the music director and conductor of the Fort Smith (John Jeter, Music Director) AMERICAN CLASSICS Symphony since 1997. He is also the recipient of the 2002 Helen M. Thompson Award presented by the American Symphony Orchestra League. This award is given First Violin Viola Mark Phillips Jack Jackson, II to one outstanding ‘early career’ music director in the United States every two years. Elizabeth Lyon, Darrel Barnes, Principal John Widder Jane Waters-Showalter Concertmaster Anitra Fay, Marlo Williams It is one of the few awards given to conductors in America. He is the recipient of the Trumpet Mayor’s Achievement Award for his services to the City of Fort Smith. John Jeter has Lori Fay, Assistant Principal Nicholas Barnaby Jesse Collett Samuel Hinson Angela Richards, Principal WILLIAM GRANT STILL guest conducted numerous orchestras including the Springfield Symphony, Karen Jeter, Ryan Gardner Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Oklahoma City Philharmonic, Arkansas Associate Concertmasters Kirsten Weingartner Weiss Kathy Murray Flute Penny Schimek Symphony Orchestra, North Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, Charleston Symphony, Gulf Coast Symphony and Illinois Carol Harrison, Elizabeth Shuhan, Symphonies Nos. 4 and 5 Chamber Symphony among many others. He co-hosts two radio programmes and is involved in many radio and Densi Rushing, Mary Ann Saylor Trombone Erika C. Lawson Principal television projects concerning classical music. He received his formal education at the University of Hartford’s Hartt Er-Gene Kahng, Emmaline McLeod Brian Haapanen, Principal School of Music and Butler University’s Jordan College of Fine Arts. -

Chapter 21 on Modal Mixture

CHAPTER21 Modal Mixture Much music of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries commonly employs a type of chromaticism that cannot be said to derive from applied functions and tonicization. In fact, the chromaticism often appears to be nonfunctional-a mere coloring of the melodic and harmonic surface of the music. Listen to the two phrases of Example 21.1. The first phrase (mm. 1-8) contains exclusively diatonic harmonies, but the second phrase (mm. 11-21) is full of chromaticism. This creates sonorities, such as the A~-major chord in m. 15, which appear to be distant from the underlying F-major tonic. The chromatic harmonies in mm. 11-20 have been labeled with letter names that indicate the root and quality of the chord. EXAMPLE 21.1 Mascagni, "A casa amici" ("Homeward, friends"), Cavalleria Rusticana, scene 9 418 CHAPTER 21 MODAL MIXTURE 419 These sonorities share an important feature: All but the cadential V-I are members of the parallel mode, F minor. Viewing this progression through the lens of F minor reveals a simple bass arpeggiation that briefly tonicizes 420 THE COMPLETE MUSICIAN III (A~), then moves to PD and D, followed by a final resolution to major tonic in the major mode. The Mascagni excerpt is quite remarkable in its tonal plan. Although it begins and ends in F major, a significant portion of the music behaves as though written in F minor. This technique of borrowing harmonies from the parallel mode is called modal mixture (sometimes known simply as mixture). We have already encountered two instances of modal mixture. -

Music 160A Class Notes Dr. Rothfarb October 8, 2007 Key

Music 160A class notes Dr. Rothfarb October 8, 2007 Key determination: • Large-scale form in tonal music goes hand in hand with key organization. Your ability to recognize and describe formal structure will be largely dependent on your ability to recognize key areas and your knowledge of what to expect. Knowing what to expect: • Knowing what keys to expect in certain situations will be an invaluable tool in formal analysis. Certain keys are common and should be expected as typical destinations for modulation (we will use Roman numerals to indicate the relation to the home key). Here are the common structural key areas: o V o vi • Other keys are uncommon for modulation and are not structural: o ii o iii o IV Tonicization or modulation?: • The phenomena of tonicization and modulation provide a challenge to the music analyst. In both cases, one encounters pitches and harmonies that are foreign to the home key. How then, does one determine whether a particular passage is a tonicization or a modulation? • To begin with, this is a question of scale. Tonicizations are much shorter than modulations. A tonicization may last only one or two beats, while a modulation will last much longer—sometimes for entire sections. • A modulation will have cadences. These cadences confirm for the listener that the music has moved to a new key area. A tonicization—though it might have more than two chords—will not have cadences. • A modulation will also typically contain a new theme. Tonicizations, on the other hand, are finished too quickly to be given any significant thematic material. -

![[Sample Title Page]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7574/sample-title-page-1017574.webp)

[Sample Title Page]

ART SONGS OF WILLIAM GRANT STILL by Juliet Gilchrist Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Chair ______________________________________ Patricia Havranek ______________________________________ Marietta Simpson January 27, 2020 ii To my mom and dad, who have given me everything: teaching me about music, how to serve others, and, most importantly, eternal principles. Thank you for always being there. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. vi Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Childhood influences and upbringing ............................................................................ 5 Chapter 3: Still, -

Secondary Dominant Chords.Mus

Secondary Dominants Chromaticism - defined by the use of pitches outside of a diatonic key * nonessential chromaticism describes the use of chromatic non-chord tones * essential chromaticism describes the use of chromatic chord tones creating altered chords Secondary Function Chords - also referred to as applied chords * most common chromatically altered chords * function to tonicize (make sound like tonic) a chord other than tonic * applied to a chord other than tonic and typically function like a dominant or leading-tone chord - secondary function chords can also be used in 2nd inversion as passing and neighbor chords - since only major or minor triads can function as tonic, only major or minor triads may be tonicized - Secondary function chords are labeled with two Roman numerals separated by a slash (/) * the first Roman numeral labels the function of the chord (i.e. V, V7, viiº, or viiº7) * the second Roman numeral labels the chord it is applied to - the tonicized chord * secondary function labels are read as V of __, or viiº of __, etc. Secondary Dominant Chords - most common type of secondardy function chords * always spelled as a major triad or Mm7 chord * used to tonicize a chord whose root is a 5th below (or 4th above) * can create stronger harmonic progressions or emphasize chords other than tonic Spelling Secondary Dominant Chords - there are three steps in spelling a secondary dominant chord * find the root of the chord to be tonicized * determine the pitch a P5 above (or P4 below) * using that pitch as the root, spell a -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices. -

The Life and Solo Vocal Works of Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) Alethea N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 The Life and Solo Vocal Works of Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) Alethea N. Kilgore Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE LIFE AND SOLO VOCAL WORKS OF MARGARET ALLISON BONDS (1913-1972) By ALETHEA N. KILGORE A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alethea N. Kilgore All Rights Reserved Alethea N. Kilgore defended this treatise on September 20, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Wanda Brister Rachwal Professor Directing Treatise Matthew Shaftel University Representative Timothy Hoekman Committee Member Marcía Porter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to the music and memory of Margaret Allison Bonds. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to acknowledge the faculty of the Florida State University College of Music, including the committee members who presided over this treatise: Dr. Wanda Brister Rachwal, Dr. Timothy Hoekman, Dr. Marcía Porter, and Dr. Matthew Shaftel. I would also like to thank Dr. Louise Toppin, Director of the Vocal Department of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for assisting me in this research by providing manuscripts of Bonds’s solo vocal works. She graciously invited me to serve as a lecturer and performer at A Symposium of Celebration: Margaret Allison Bonds (1913-1972) and the Women of Chicago on March 2-3, 2013. -

William Grant Still's Three Rhythmic Spirituals

William Grant Still’s Three Rhythmic Spirituals Jeff rey L. Webb William Grant Stil l, frequently referred only recently have major symphony orchestras to as “the Dean” of African American begun to program Still’s symphonic works such composers, was born in Woodville, Mis- as the Afro-American Symphony. sissippi, in 1895. Still was a prolifi c com- Still was equally adept at writing works for poser who wrote music for all idioms and the voice, both solo and choral. Along with was the fi rst African American to have his peers such as William L. Dawson (1899-1990), works performed by a major American Still was especially fond of composing and symphony orchestra; conduct a major arranging African American Spirituals and symphony orchestra in the United States wrote dozens of spiritual arrangements for (Los Angeles Philharmonic, 1936); and a variety of vocalists. While Dawson’s cho- selected to compose theme music for ral arrangements of spirituals are showcased the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City. quite often, Still’s contributions are still not as Though Still broke down many barriers readily performed. Three Rhythmic Spirituals is a for African Americans in the world of collection of three separate pieces arranged by classical music, he still found it diffi cult to William Grant Still: “Lord, I Looked Down the fi nd groups to program his music. As a re- Road,” “Hard Trials,” and “Holy Spirit, Don’t sult, many of his compositions never had You Leave Me.” The following article provides noted performances until long after he a short biography of Still, a history of Three had written them. -

AMERICAN CLASSICS WILLIAM GRANT STILL Afro-American Symphony in Memoriam • Africa

559174bk 11/1/05 9:40 pm Page 8 das Werk sechsmal, bevor er es merkwürdigerweise zu- sprochene Ängste und lauernde Schrecken“ aus. Das rückzog und unpubliziert ließ. Eingangsthema spiegelt afrikanische Naturreligion und MERICAN LASSICS In Africa entwirft Still ein Bild der afrikanischen führt zu einem orientalischen Motiv, das sich auf Nord- A C Geschichte im Stile der exotisierenden Orchesterwerke afrika und muslimische Einflüsse bezieht. Still entfaltet von Rimsky-Korsakov. Der erste Satz Land of Peace hat im gesamten Werk eine ungewöhnliche Kreativität, um zwei Themen, die das Ländliche und das Spirituelle be- ein facettenreiches Bild des lebendigen afrikanischen schreiben. Der zweite Satz Land of Romance reflektiert Geistes zu vermitteln. Traurigkeit und führt am Ende zu leidenschaftlicher WILLIAM GRANT STILL Sehnsucht. Das Finale Land of Superstition drückt – mit David Ciucevich den Worten von Stills Frau Verna Arvey – „unausge- Deutsche Fassung: Thomas Theise Afro-American Symphony In Memoriam • Africa (Symphonic Poem) Fort Smith Symphony John Jeter 8.559174 8 559174bk 11/1/05 9:40 pm Page 2 William Grant Still (1895-1978) Verse von Paul Lawrence Dunbar hinzu, um die Stim- Shuffle Along auftrat. Als einander Zeitgenossen, die in Symphony No. 1 ‘Afro-American’ (1930) mung der einzelnen Sätze deutlich zu machen. Als tief denselben Kreisen verkehrten und wertschätzten, In Memoriam: The Colored Soldiers Who Died for Democracy (1943) • Africa (1930) religiöser Mensch widmete er dieses – wie auch jedes beeinflussten sie sich bewusst und -

Works by WILLIAM GRANT STILL New World Records 80399 VIDEMUS

Works by WILLIAM GRANT STILL New World Records 80399 VIDEMUS William Grant Still (1895-1978) has often been termed the patriarchal figure in Black music and was the first Afro-American composer to secure extensive publication and significant performances. His works represent the culmination of musical aspirations of the Harlem Renaissance, in that they “elevated” folkloric materials. Such a concept, however, had been employed occasionally by earlier figures, including Harry T. Burleigh (1868-1949), Clarence Cameron White (1880-1960), R. Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943, New World NW 367), and Still’s Afro-British model and cultural hero, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912). Still was born in Woodville, Mississippi, and his early days were spent in Little Rock, Arkansas, where his mother moved after his father’s early death. His stepfather was a record collector, and those early opera discs and Still’s violin studies stimulated the youth’s interest in music. On graduation from high school, Still planned to study for a medical career, but his love of music was intensified at Wilberforce College in Ohio, and especially at Oberlin, where he heard a full orchestra for the first time. During this period, he worked in Memphis for W.C. Handy, subsequently joining him when Handy moved to New York City. In 1921 Hall Johnson recommended him as oboist for Ebie Blake’s Shuffle Along (NW 260) and, while touring in Boston with the show, Still secured composition lessons from George Whitfield Chadwick. After his return to New York, he studied with Edgard Varèse, although any avant-garde influence form this composer remains lost in Still’s earlier, withdrawn works.