Prospects for Aquaculture Diversification in Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AQUA Y~Zi,"Ives Guidelines for Shellfish Farmingin Alaska

1 AQUA y~Zi,"ives Guidelines for Shellfish Farmingin Alaska Brian C. Paust MarineAdvisory Program Petersburg,Alaska RaymondRaLonde MarineAnchorage,Advisory Program XIIIIIIW% I,r"IP g ]on: NATIONALSEA GRANT DEPQSITQRY PFLLLIBRARY BUILDING URI NARRAGANSETTBAYCAMPUS 4APRAGANSETT,R.l02882 AlaskaSea Grant College Program PO.Box 755040 ~ Universityof AlaskaFairbanks Fairbanks,Alaska 99775-5040 907! 474.6707~ Fax 907!474-6285 http://www.uaf.alaska.edu/seagrant AN-16~ 1997~ Price:$4.00 ElmerE. RasmusonLibrary Cataloging-in-Publication Data Contents Paust, Brian C. Guidelinesfor shellfish farming in Alaska / Brian C. Paust,Raymond RaLonde. The Authors . Introduction . Aquaculture notes; no. 16! Marine Advisory Program The Roadto SuccessfulShellfish Farming . Starting the Business. ISBN 1-56612-050-0 Follow These Steps No Precise Instructions Available 3 1. Shellfishculture Alaska. 2. Oysterculture Alaska. I. RaLonde, Aquaculture Business on a Small Scale . Raymond. Il. Alaska SeaGrant College Program. III. Title. IV. Series. PictureYourself as an Aquatic Farmer 4 4 The Need to Be Optimistic and Innovative SH371,P38 1997 What Niche Do You Want to Fill in Aquatic Farming?... ..... 4 Practical Experience ls Necessary Be Sure Information Is Accurate 5 5 Be Cautious of Claims of High Profits Beware of the Gold RushMentality 6 7 Checklist Before You Invest. ..... 7 Financing,............... ..... 8 How Much Money Is Neededfor Investment? ..... 8 Credits Why Some ShellfishOperations Have Failed. 9 Major Constraints Facingthe Industry , 10 Cover design is by SusanGibson, editing is by Sue Keller, and Tips on Reducing Business Risk . 11 layout is by Carol Kaynor. The Market for Alaska Shellfish . .,11 Thisbook is the resultof work sponsoredby the Universityof AlaskaSea Grant College Program, which iscooperatively supported by ShellfishAquaculture Techniques .. -

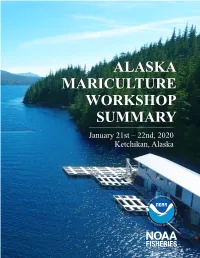

Alaska Mariculture Workshop Summary

ALASKAALASKA MARICULTUREMARICULTURE WORKSHOPWORKSHOP SUMMARYSUMMARY January 21st – 22nd, 2020 Ketchikan, Alaska Alaska Mariculture Workshop Workshop Summary NOAA Fisheries Alaska Regional Office National Marine Fisheries Service and Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, 2020. Summary of the Alaska Mariculture Workshop. 21–22 January 2020, Ketchikan, Alaska, prepared by Seatone Consulting, 58 pp. All photos courtesy of NOAA Fisheries, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game or Seatone Consulting unless otherwise noted. ... WORKSHOP SUMMARY This workshop was hosted by the NOAA Fisheries Office of January 21st – 22nd, 2020, Ketchikan, Alaska Aquaculture and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OFFICE OF AQUACULTURE NOAA's Office of Aquaculture supports the development of Mariculture—considered in the State of Alaska to be the sustainable aquaculture in the enhancement, restoration, and farming of shellfish and United States. Its work focuses on seaweed—is a burgeoning industry in this region of the United regulation and policy, science and States. The Alaska Mariculture Task Force (Task Force) research, outreach and education, established a goal of developing a $100 million industry in 20 and international activities. years and outlined recommendations to achieve this goal in the 2018 Mariculture Development Plan (Development Plan). To ALASKA REGIONAL OFFICE help Alaskans advance towards this ambitious goal, the National NOAA Fisheries Alaska Regional Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Marine Office promotes science-based stewardship of Alaska's marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) and Pacific States Marine resources and their habitats in the Fisheries Commission (PSMFC) convened a multi-day Gulf of Alaska, eastern Bering Sea, workshop with more than 60 mariculture development and Arctic oceans. -

Marine Resources

AKU-G-92-006 C3 Marine Resources MARINE ADVISORY: PROGRAM Vol. VII No. 4 UNIVERSITY Of ALASKA —BBftHWB OK—- December 1992 In This Issue: Growing Shemish in Alaska l0^' coPy,. "A/ ':•' Shellfish Aquaculture in Alaska: Its Promise and Constraints If you hope to succeed in the growing Alaskan shellfish industry, a good understanding of what is involved is required. Marine Advisory aquaculture specialist, Ray RaLonde, describes some of the history and the culture pro cess for a variety of species that are possible in Alaska 2 Aquatic Farm Permits Prior to 1988 aquatic farm permitting was a confusing and lengthy ordeal. Regulations were often unclear or non-existent. But with passage of the aquatic farm act, permit processing became formalized. However, for many people the process is still difficult to understand. Mariculture coordinator for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Jim Cochran, explains what you need to know to get started Commercial Oyster Farming: Part ofStudents Training In 1989 Petersburg high school instructor, Jack Eddy, conducted shellfish and plankton research in his area with the hopes of establishing a school aquaculture program. With the students involved from the beginning, a program was established with grant money. It has been so successful that it is now in the process of becoming a self-sustaining business with a scholar ship program Sea Farming Alaska Style Long time oyster farmer, Don Nickolson tells it like it is. Oyster farming in Alaska is not a retirement occupation. It involves long hours and resource fulness. But most of all he says it requires perseveranoe Is Aquatic Farming in Alaska for You? If you are considering shellfishaquaculture, this checklistcan help you determine whether aquatic farming is feasible for your particular situation. -

Alaska Mariculture Development Plan

ALASKA MARICULTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN STATE OF ALASKA MARCH 23, 2018 DRAFT Alaska Mariculture Development Plan // 1 Photo credit clockwise from top left: King crab juvenile by Celeste Leroux; bull kelp provided by Barnacle Foods; algae tanks in OceansAlaska shellfish hatchery provided by OceansAlaska; fertile blade of ribbon kelp provided by Hump Island Oyster Co.; spawning sea cucumber provided by SARDFA; icebergs in pristine Alaska waters provided by Alaska Seafood. Cover photos: Large photo: Bull kelp by ©“TheMarineDetective.com”. Small photos from left to right: Oyster spat ready for sale in a nursery FLUPSY by Cynthia Pring-Ham; juvenile king crab by Celeste Leroux; oyster and seaweed farm near Ketchikan, Alaska, provided by Hump Island Oyster Co. Back cover photos from left to right: Nick Mangini harvests kelp on Kodiak Island, by Trevor Sande; oysters on the half-shell, by Jakolof Bay Oyster Company; oyster spat which is set, by OceansAlaska. Photo bottom: “Mariculture – Made in Alaska” graphic provided by Alaska Dept. of Commerce, Community and Economic Development, Division of Economic Development Layout and design by Naomi Hagelund, Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association (APICDA). This publication was created in part with support from the State of Alaska. This publication was funded in part by NOAA Award #NA14NMF4270058. The statements are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or the U.S. Dept. of Commerce. 2 // Alaska Mariculture Development Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from -

VELOPMENT Alaska Sea Grant Director Ronald Dearborn and UAJ School of Fisherie

Fishlines, 1986 Item Type Journal Publisher University of Alaska, Office for Fisheries Download date 04/10/2021 16:17:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8680 .. Volume VI, No. 1 February 7, 1986 Office for Fisheries University of Alaska AQUACULTURE POLICY UNDER DE VELOPMENT Alaska Sea Grant Director Ronald Applications should include current Dearborn and UAJ School of Fisheries vitae, statement of career objective, Dean Ole Mathisen have been among and letter of recommendation from the those on an advisory committee de major professor or department head. veloping a state mariculture policy. Submit applications to the Fisheries Other committee members include re Internship Program; Alaska Sea Grant presentatives of fishermen's organi College Program; cl o SWOHRD; Univer zations, processors, Native organi sity of Alaska; Bunnell Bldg., Room 1; zations and government agencies. The 99775-5400. committee has reported findings to Governor Bill Sheffield and his mini ALASKA NORTHWEST PUBLISHING cabinet on fisheries. Both the execu PREMIERS TWO MARINE BOOKS tive and legislative branches anticipate further activity by this committee. Two popular marine publications were Dearborn and Mathisen have offered to distributed last month that might be continue their participation in this useful in classroom instruction. Plant discussion of the state's aquaculture Lore of An Alaskan Island ($9. 95) and plans. Alciski's Saltwater Fishes and Other Sea Life ($19.95) are now-available FISHERIES INTERNSHIP AVAILABLE from --xlaska Northwest Publishing Company and at local book stores. The Alaska Sea Grant Program and the North Pacific Fishery Management The plant lore book began in an adult Council have established a summer education class on Spruce Island near internship for students in the Universi Kodiak. -

Open Ocean Aquaculture

Open Ocean Aquaculture Harold F. Upton Analyst in Natural Resources Policy Eugene H. Buck Specialist in Natural Resources Policy August 9, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32694 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Open Ocean Aquaculture Summary Open ocean aquaculture is broadly defined as the rearing of marine organisms in exposed areas beyond significant coastal influence. Open ocean aquaculture employs less control over organisms and the surrounding environment than do inshore and land-based aquaculture, which are often undertaken in enclosures, such as ponds. When aquaculture operations are located beyond coastal state jurisdiction, within the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ; generally 3 to 200 nautical miles from shore), they are regulated primarily by federal agencies. Thus far, only a few aquaculture research facilities have operated in the U.S. EEZ. To date, all commercial aquaculture facilities have been sited in nearshore waters under state or territorial jurisdiction. Development of commercial aquaculture facilities in federal waters is hampered by an unclear regulatory process for the EEZ, and technical uncertainties related to working in offshore areas. Regulatory uncertainty has been identified by the Administration as the major barrier to developing open ocean aquaculture. Uncertainties often translate into barriers to commercial investment. Potential environmental and economic impacts and associated controversy have also likely contributed to slowing expansion. Proponents of open ocean aquaculture believe it is the beginning of the “blue revolution”—a period of broad advances in culture methods and associated increases in production. Critics raise concerns about environmental protection and potential impacts on existing commercial fisheries. -

Growing Shellfish in Alaska

MARINE ADVISORY PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA Vol. VII No. 4 December 1992 In This Issue: Growing Shellfish in Alaska f Pacific Oysters Shellfish Aquaculture in Alaska: Its Promise and Constraints Locations If you hope to succeed in the growing Alaskan shellfish industry, a good s understanding of what is involved is required. Marine Advisory aquaculture atat ngton State specialist, Ray RaLonde, describes some of the history and the culture pro- British Columbia Jun April November Prince William Sound June April cess for a variety of species that are possible in Alaska. .2 Select species to Aquatic Farm Permits culture Select potential site(s) Site survey(s) Prior to 1988 aquatic farm permitting was a confusing and lengthy ordeal. Yes No DNR site Possible problems Aquatic farm Aquatic farm permit suitablity appl. with site application opening application No Yes ADF&G transport No COE permit Floating or permit appl. required submersed structure Regulations were often unclear or non-existent. But with passage of the One year site Uplands required? trials Site trials Yes positive aquatic farm act, permit processing became formalized. However, for many No Submit To DNR: (during 60 day application period) 1) Aquatic farm application 2) Coastal project questionnaire 3) Federal applications (copies) Special area Permit (To DFG) Include in aquatic farm application people the process is still difficult to understand. Mariculture coordinator Agency review Additional information request for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Jim Cochran, explains what ACMP dii you need to know to get started. 6 Commercial Oyster Farming: Part of Students Training In 1989 Petersburg high school instructor, Jack Eddy, conducted shellfish and plankton research in his area with the hopes of establishing a school aquaculture program. -

Alaskan Sea Ranching

FISH HEALTH, ETC. but runs severely diminished by the nook salmon fingerlings. Estimates 1910’s. This caused the canneries to are that these represent about 22% finally come around, although they of the harvested salmon in Alaskan struggled with the mandate of 50% Alaskan waters each year. They are initially escapement (to allow broods to go put into net pens to olfactory im- upstream). This did, however work, print them on the bay, to minimize and runs increased resulting in many straying up other rivers and for fish- of the hatcheries closing down. In ermen to catch them on their return. 1933, 126.4 million salmon were Sea caught – a historical record. There are a couple each of Federal and State hatcheries that contrib- However, through the 1930’s ute, but most of this production is and 1940’s, fish traps were responsi- via non-profit regional aquaculture ble for another depletion. Hatcher- Ranching: associations (see below), plus some ies came back into the picture both scattered independents. The catch Fig. 2. Ben Contag, manager at Port Armstrong, AK of Armstrong-Keta. by the Alaska Territory Fishery Yes, they do “do ends up being about 2 to 3% of Service and the US Department of what is released from hatcheries. back and positioned wild salmon as gles. In the early days, there was Fisheries, but this did not help the aquaculture” in Alaska I try and probe for his sentiments a premium product. The result has little management of the stocks and two-decade decline. In 1959 only on why Alaskans don’t also raise been a revitalization of the salmon over-fishing severely impacted re- 25 million salmon were harvested salmon right through their life cycle fishing industry and a rejuvenation turns. -

The Blue Economy in the Arctic Ocean: Governing Aquaculture in Alaska and North Norway

Andreas Raspotnik, Svein V. Rottem, Andreas Østhagen. The Blue Economy… 107 UDC: 341.225(739.8)(481.7)(045) DOI: 10.37482/issn2221-2698.2021.42.122 The Blue Economy in the Arctic Ocean: Governing Aquaculture in Alaska and North Norway © Andreas RASPOTNIK, PhD, senior researcher E-mail: [email protected] High North Centre for Business and Governance, Nord University, Bodø, Norway © Svein V. ROTTEM, PhD, senior fellow E-mail: [email protected] Fridtjof Nansen Institute, Lysaker, Norway © Andreas ØSTHAGEN, PhD, senior fellow E-mail: [email protected] Fridtjof Nansen Institute, Lysaker, Norway Abstract. In the Arctic, the concept of the blue economy is increasingly dominating discussions on regional development. This entails utilising the region’s ocean-based resources in a sustainable way — both from a global and local level, as well as from an environmental and economic perspective. A crucial aspect in this development is how blue activities are regulated. The UNCLOS-regime plays a vital part in providing the mechanisms and procedures for states to manage marine resources more broadly. However, the predomi- nant mode of governance for Arctic maritime activities will remain unilateral management by each of the coastal states. Thus, the national and local legal and political framework needs to be mapped. In this article we will explore and explain how aqua/-mariculture is governed in the United States (Alaska) and Norway (North Norway). This will be done by examining how parameters for blue economic projects are defined and determined at the international, regional, national and local governance level. Thus, our article will il- lustrate the complexity behind the blue economy. -

Marine Resource Management Final Report Analysis and Review of Policy, Decision Making and Politics Regarding Finfish Aquaculture in Alaska

ANALYSIS AND REVIEW OF POLICY, DECISION MAKING AND POLITICS REGARDING FINFISH AQUACULTURE IN ALASKA by BRENT C. PAINE MARINE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT FINAL REPORT ANALYSIS AND REVIEW OF POLICY, DECISION MAKING AND POLITICS REGARDING FINFISH AQUACULTURE IN ALASKA by BRENT CONRAD PAINE Submitted To Marine Resource Management Program College of Oceanography Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331 1991 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Commencement Winter, 1991 Internship: Alaska Finfish Farming Task Force TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1. OVERVIEW 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Statement of Problem 2 1.3 Objectives and methods 3 Section 2. REVIEW OF WORLD AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT 4 2.1 Global Trends 4 2.2 World Commercial Salmon Fishery Production 7 2.3 Historical Background of Salmon Farmings Growth 11 2.3.1 Norway 14 2.3.2 Scotland 18 2.3.3 Canada 21 2.3.3.1 British Columbia 22 2.3.3.2 New Brunswick 23 2.3.3.3 Salmon Aquaculture Policy in British Columbia 25 2.3.4 Chile 27 2.3.5 Washington State 28 2.3.6 Finfish Aquaculture Policy in the United States 31 2.4 Market Impacts Due to Increased Production of Farmed Salmon 33 Section 3. FINFISH FARMING IN ALASKA 38 3.1 Introduction 38 3.2 History of Events in Alaska 39 3.3 Legislative Review and Action 42 3.4 Major Issues Presented in the Finfish Farming Debate 48 3.5.1 Disease and Genetic Concerns 48 3.5.2 Environmental Impacts 53 3.5.3 Site Conflicts and Aesthetic Issues 55 3.5.4 Market Concerns 58 3.5 The Alaska Finfish Farming Task Force 59 Section 4. -

Alaska Mariculture Development Plan, March 23, 2018

ALASKA MARICULTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN STATE OF ALASKA MARCH 23, 2018 Alaska Mariculture Development Plan // 1 Photo credit clockwise from top left: King crab juvenile by Celeste Leroux; bull kelp provided by Barnacle Foods; algae tanks in OceansAlaska shellfsh hatchery provided by OceansAlaska; fertile blade of ribbon kelp provided by Hump Island Oyster Co.; spawning sea cucumber provided by SARDFA; icebergs in pristine Alaska waters provided by Alaska Seafood. Cover photos: Large photo: Bull kelp by ©“TheMarineDetective.com”. Small photos from left to right: Oyster spat ready for sale in a nursery FLUPSY by Cynthia Pring-Ham; juvenile king crab by Celeste Leroux; oyster and seaweed farm near Ketchikan, Alaska, provided by Hump Island Oyster Co. Back cover photos from left to right: Nick Mangini of Kodiak Island Sustainable Seaweed harvests kelp, by Trevor Sande; oysters on the half-shell, by Jakolof Bay Oyster Company; oyster spat which is set, by OceansAlaska. Photo bottom: “Mariculture – Made in Alaska” graphic by artist Craig Updegrove and provided by Alaska Dept. of Commerce, Community and Economic Development, Division of Economic Development Layout and design by Naomi Hagelund, Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association (APICDA). This publication was created in part with support from the State of Alaska. This publication was funded in part by NOAA Award #NA14NMF4270058. The statements are those of the authors and do not necessarily refect the views of NOAA or the U.S. Dept. of Commerce. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Message -

U.S. Offshore Aquaculture Regulation and Development

U.S. Offshore Aquaculture Regulation and Development October 10, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45952 SUMMARY R45952 U.S. Offshore Aquaculture Regulation and October 10, 2019 Development Harold F. Upton Regulatory uncertainty has been identified as one of the main barriers to offshore aquaculture Analyst in Natural development in the United States. Many industry observers have emphasized that congressional Resources Policy action may be necessary to provide statutory authority to develop aquaculture in offshore areas. Offshore aquaculture is generally defined as the rearing of marine organisms in ocean waters beyond significant coastal influence, primarily in the federal waters of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Establishing an offshore aquaculture operation is contingent on obtaining several federal permits and fulfilling a number of additional consultation and review requirements from different federal agencies responsible for various general authorities that apply to aquaculture. However, there is no explicit statutory authority for permitting and developing aquaculture in federal waters. The aquaculture permit and consultation process in federal waters has been described as complex, time consuming, and difficult to navigate. Supporters of aquaculture have asserted that development of the industry, especially in offshore areas, has significant potential to increase U.S. seafood production and provide economic opportunities for coastal communities. Currently, marine aquaculture facilities are located in nearshore state waters. Although there are some research-focused and proposed commercial offshore facilities, no commercial facilities are currently operating in U.S. federal waters. Aquaculture supporters note that the extensive U.S. coastline and adjacent U.S. ocean waters provide potential sites for offshore aquaculture development.