The Development of the Armourers' Crafts and the Forging Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Author Index (Print)

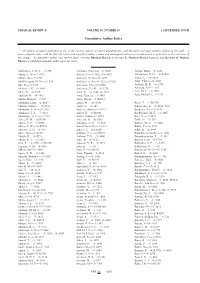

PHYSICAL REVIEW B VOLUME 58, NUMBER 10 1 SEPTEMBER 1998-II Cumulative Author Index All authors of papers published so far in the current volume are listed alphabetically with the issue and page numbers following the dash. A more complete index, with the full title listed with each ®rst author's name and subsequent authors cross-referenced, is published in the last issue of the volume. A cumulative author and subject index covering Physical Review A through E, Physical Review Letters, and Reviews of Modern Physics is published annually under separate cover. AaraÄo Reis, F. D. A.Ð͑1͒ 394 Ancilotto, FrancescoÐ͑8͒ 5085 Awaga, KunioÐ͑5͒ 2438 Abarra, E. N.Ð͑9͒ 5672 Anders, S.Ð͑9͒ 5825; ͑10͒ 6639 Awschalom, D. D.Ð͑8͒ R4238 Abbate, M.Ð͑7͒ 3755 Andersen, N. H.Ð͑10͒ 6291 AxnaÈs, J.Ð͑10͒ 6628 Abd-Elmeguid, M. M.Ð͑1͒ 254 Andersen, O. K.Ð͑1͒ 522; ͑2͒ 1025 Ayaz, YuÈkselÐ͑4͒ 2001 Abe, K.Ð͑5͒ 2513 Andersson, M.Ð͑10͒ 6580 Aydinol, M. K.Ð͑6͒ 2975 Abelson, J. R.Ð͑8͒ 4803 Andersson, Per H.Ð͑9͒ 5230 Azevedo, A.Ð͑1͒ 101 Abliz, M.Ð͑9͒ 5205 Ando, K.Ð͑3͒ 1100; ͑4͒ 1912 Aziz, M. J.Ð͑8͒ 4579 Abolfath, M.Ð͑4͒ 2013 Ando, TsuneyaÐ͑3͒ 1485 Aziz, Michael J.Ð͑1͒ 189 Abraha, KamsulÐ͑2͒ 897 Ando, YoichiÐ͑6͒ R2913 Abrahams, ElihuÐ͑2͒ R559 AndraÈ, W.Ð͑10͒ 6346 Baars, T.Ð͑4͒ R1750 Abramo, Maria C.Ð͑5͒ 2372 AndreÂ, G.Ð͑2͒ 847 Baberschke, K.Ð͑9͒ 5611, 5701 Abrikosov, A. A.Ð͑5͒ 2788 Andreev, AntonÐ͑9͒ 5149 Bacherler, Th.Ð͑3͒ 1633 Abrikosov, I. A.Ð͑7͒ 3613 Andrei, N.Ð͑6͒ R2921 Bachlechner, M. E.Ð͑4͒ 1887 Abrosimov, N. -

Chaucer's Official Life

CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE JAMES ROOT HULBERT CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE Table of Contents CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE..............................................................................................................................1 JAMES ROOT HULBERT............................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................4 THE ESQUIRES OF THE KING'S HOUSEHOLD...................................................................................................7 THEIR FAMILIES........................................................................................................................................8 APPOINTMENT.........................................................................................................................................12 CLASSIFICATION.....................................................................................................................................13 SERVICES...................................................................................................................................................16 REWARDS..................................................................................................................................................18 -

The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany

Kathrin Dräger, Mirjam Schmuck, Germany 319 The German Surname Atlas Project ± Computer-Based Surname Geography Kathrin Dräger Mirjam Schmuck Germany Abstract The German Surname Atlas (Deutscher Familiennamenatlas, DFA) project is presented below. The surname maps are based on German fixed network telephone lines (in 2005) with German postal districts as graticules. In our project, we use this data to explore the areal variation in lexical (e.g., Schröder/Schneider µtailor¶) as well as phonological (e.g., Hauser/Häuser/Heuser) and morphological (e.g., patronyms such as Petersen/Peters/Peter) aspects of German surnames. German surnames emerged quite early on and preserve linguistic material which is up to 900 years old. This enables us to draw conclusions from today¶s areal distribution, e.g., on medieval dialect variation, writing traditions and cultural life. Containing not only German surnames but also foreign names, our huge database opens up possibilities for new areas of research, such as surnames and migration. Due to the close contact with Slavonic languages (original Slavonic population in the east, former eastern territories, migration), original Slavonic surnames make up the largest part of the foreign names (e.g., ±ski 16,386 types/293,474 tokens). Various adaptations from Slavonic to German and vice versa occurred. These included graphical (e.g., Dobschinski < Dobrzynski) as well as morphological adaptations (hybrid forms: e.g., Fuhrmanski) and folk-etymological reinterpretations (e.g., Rehsack < Czech Reåak). *** 1. The German surname system In the German speech area, people generally started to use an addition to their given names from the eleventh to the sixteenth century, some even later. -

High Treason

11th October 2017 High Treason The first Treason Act in England was enacted by Parliament at the time of Edward III in 1351, which codified the common law of Treason and contained most of acts defined as Treason. It is still in force but has been very significantly amended (Wikipedia - Treason Act 1351). The main definitions relate to any person planning or imagined: “to harm the King or his immediate family, his sons and heirs or their companions; levying war against the King, plus actions against the King's officials, counterfeiting the Great Seal. Privy Seal or coinage of the realm.” The definitions also included that any person who "adhered to the King's enemies in his Realm, giving them aid and comfort in his Realm or elsewhere was guilty of High Treason" The penalty for these offences at the time was Hanging, Drawing and Quartering. The Act is still in force today (without the "drawing and quartering part") The Act was last used to prosecute William Joyce in 1945, who was subsequently hanged for collaborating with Germany during WWII More recently the Treason Felony Act (1848) declared that It is treason felony to: "compass, imagine, invent, devise, or intend: • to deprive the Queen of her crown, • to levy war against the Queen, or • to "move or stir" any foreigner to invade the United Kingdom or any other country belonging to the Queen.” Blair and the New Labour government enacted The Crime and Disorder Act (1998) which amended The Treason Felony Act (1848) and formally abolished the death penalty for the last offences carrying it, namely treason and piracy. -

What If the Founders Had Not Constitutionalized the Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus?

THE COUNTERFACTUAL THAT CAME TO PASS: WHAT IF THE FOUNDERS HAD NOT CONSTITUTIONALIZED THE PRIVILEGE OF THE WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS? AMANDA L. TYLER* INTRODUCTION Unlike the other participants in this Symposium, my contribution explores a constitutional counterfactual that has actually come to pass. Or so I will argue it has. What if, this Essay asks, the Founding generation had not constitutionalized the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus? As is explored below, in many respects, the legal framework within which we are detaining suspected terrorists in this country today—particularly suspected terrorists who are citizens1—suggests that our current legal regime stands no differently than the English legal framework from which it sprang some two-hundred-plus years ago. That framework, by contrast to our own, does not enshrine the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus as a right enjoyed by reason of a binding and supreme constitution. Instead, English law views the privilege as a right that exists at the pleasure of Parliament and is, accordingly, subject to legislative override. As is also shown below, a comparative inquiry into the existing state of detention law in this country and in the United Kingdom reveals a notable contrast—namely, notwithstanding their lack of a constitutionally- based right to the privilege, British citizens detained in the United Kingdom without formal charges on suspicion of terrorist activities enjoy the benefit of far more legal protections than their counterparts in this country. The Essay proceeds as follows: Part I offers an overview of key aspects of the development of the privilege and the concept of suspension, both in England and the American Colonies, in the period leading up to ratification of the Suspension Clause as part of the United States Constitution. -

News, Information, and Documentary Culture in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: “TAKE WRITING”: NEWS, INFORMATION, AND DOCUMENTARY CULTURE IN LATE MEDIEVAL ENGLAND Hyunyang Kim Lim, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Dissertation directed by: Professor Theresa Coletti Department of English This dissertation analyzes late medieval English texts in order to understand how they respond to the anxieties of a society experiencing the growing passion for news and the development of documentary culture. The author’s reading of the Paston letters, Chaucer’s Man of Law’s Tale , and the Digby Mary Magdalene demonstrate these texts’ common emergence in an environment preoccupied with the production and reception of documents. The discussion pays particular attention to actual and fictional letters in these texts since the intersection of two cultural forces finds expression in the proliferation of letters. As a written method of conveying and storing public information, the letters examined in this dissertation take on importance as documents. The author argues that the letters question the status of writing destabilized by the contemporary abuse of written documents. The dissertation offers a view of late medieval documentary culture in connection with early modern print culture and the growth of public media. The Introduction examines contemporary historical records and documents as a social context for the production of late medieval texts. Chapter 1 demonstrates that transmitting information about current affairs is one of the major concerns of the Pastons. The chapter argues that late medieval personal letters show an investment in documentary culture and prepared for the burgeoning of the bourgeois reading public. Whereas Chapter 1 discusses “real” letters, Chapter 2 and 3 focus on fictional letters. -

268KB***The Law on Treasonable Offences in Singapore

Published on e-First 14 April 2021 THE LAW ON TREASONABLE OFFENCES IN SINGAPORE This article aims to provide an extensive and detailed analysis of the law on treasonable offences in Singapore. It traces the historical development of the treason law in Singapore from the colonial period under British rule up until the present day, before proceeding to lay down the applicable legal principles that ought to govern these treasonable offences, drawing on authorities in the UK, India as well as other Commonwealth jurisdictions. With a more long-term view towards the reform and consolidation of the treason law in mind, this article also proposes several tentative suggestions for reform, complete with a draft bill devised by the author setting out these proposed changes. Benjamin LOW1 LLB (Hons) (National University of Singapore). “Treason doth never prosper: what’s the reason? Why, if it prosper, none dare call it treason.”2 I. Introduction 1 The law on treasonable offences, more commonly referred to as treason,3 in Singapore remains shrouded in a great deal of uncertainty and ambiguity despite having existed as part of the legal fabric of Singapore since its early days as a British colony. A student who picks up any major textbook on Singapore criminal law will find copious references to various other kinds of substantive offences, general principles of criminal liability as well as discussion of law reform even, but very little mention is made of the relevant law on treason.4 Academic commentary on this 1 The author is grateful to Julia Emma D’Cruz, the staff of the C J Koh Law Library, the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and the ISEAS Library for their able assistance in the author’s research for this article. -

PETITION List 04-30-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 Signatories as of 04/30/13 Arian A., Brooklyn, New York Ilana Abramovitch, Brooklyn, New York Clare A., Redondo Beach, California Alexis Abrams, Los Angeles, California K. A., Mexico Danielle Abrams, Ann Arbor, Michigan Kassim S. A., Malaysia Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York N. A., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Geoffrey Abrams, New York, New York Tristan A., Fort Mill, South Carolina Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Cory a'Ghobhainn, Los Angeles, California Elizabeth Abrantes, Cambridge, Canada Tajwar Aamir, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Africa Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jamshed Abbas, Vancouver, Canada Fadia Abulhajj, Minneapolis, Minnesota Mansoor Abbas, Southington, Connecticut Janne Abullarade, Seattle, Washington Andrew Abbey, Pleasanton, California Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Andrea Abbott, Oceanport, New Jersey Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Laura Abbott, Woodstock, New York Alexander Ace, New York, New York Asad Abdallah, Houston, Texas Leela Acharya, Toronto, Canada Samiha Abdeldjebar, Corsham, United Kingdom Dennis Acker, Los Angeles, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Abdifatah Abdi, Minneapolis, Minnesota Marilyn Ackerman, Brooklyn, New York Hamdiya Fatimah Abdul-Aleem, Charlotte, North Eddie Acosta, Silver Spring, Maryland Carolina Maria Acosta, -

Criminal Law Act 1967

Status: This version of this Act contains provisions that are prospective. Changes to legislation: There are currently no known outstanding effects for the Criminal Law Act 1967. (See end of Document for details) Criminal Law Act 1967 1967 CHAPTER 58 An Act to amend the law of England and Wales by abolishing the division of crimes into felonies and misdemeanours and to amend and simplify the law in respect of matters arising from or related to that division or the abolition of it; to do away (within or without England and Wales) with certain obsolete crimes together with the torts of maintenance and champerty; and for purposes connected therewith. [21st July 1967] PART I FELONY AND MISDEMEANOUR Annotations: Extent Information E1 Subject to s. 11(2)-(4) this Part shall not extend to Scotland or Northern Ireland see s. 11(1) 1 Abolition of distinction between felony and misdemeanour. (1) All distinctions between felony and misdemeanour are hereby abolished. (2) Subject to the provisions of this Act, on all matters on which a distinction has previously been made between felony and misdemeanour, including mode of trial, the law and practice in relation to all offences cognisable under the law of England and Wales (including piracy) shall be the law and practice applicable at the commencement of this Act in relation to misdemeanour. [F12 Arrest without warrant. (1) The powers of summary arrest conferred by the following subsections shall apply to offences for which the sentence is fixed by law or for which a person (not previously convicted) may under or by virtue of any enactment be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years [F2(or might be so sentenced but for the restrictions imposed by 2 Criminal Law Act 1967 (c. -

General Conference, Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018

NEW OPEN POLITICAL ACCESS JOURNAL RESEARCH FOR 2018 ECPR General Conference, Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018 EXCHANGE EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Alexandra Segerberg, Stockholm University, Sweden Simona Guerra, University of Leicester, UK Published in partnership with ECPR, PRX is a gold open access journal seeking to advance research, innovation and debate PRX across the breadth of political science. NO ARTICLE PUBLISHING CHARGES THROUGHOUT 2018–2019 General Conference bit.ly/introducing-PRX 22 – 25 August 2018 General Conference Universität Hamburg, 22 – 25 August 2018 Contents Welcome from the local organisers ........................................................................................ 2 Mayor’s welcome ..................................................................................................................... 3 Welcome from the Academic Convenors ............................................................................ 4 The European Consortium for Political Research ................................................................... 5 ECPR governance ..................................................................................................................... 6 ECPR Council .............................................................................................................................. 6 Executive Committee ................................................................................................................ 7 ECPR staff attending ................................................................................................................. -

Modernising the Law of Murder and Manslaughter: Part 1

Journal of Politics and Law; Vol. 8, No. 4; 2015 ISSN 1913-9047 E-ISSN 1913-9055 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Modernising the Law of Murder and Manslaughter: Part 1 Graham McBain1,2 1 Peterhouse, Cambridge, UK 2 Harvard Law School, USA Correspondence: Graham McBain, 21 Millmead Terrace, Guildford, Surrey GU2 4AT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 17, 2015 Accepted: November 2, 2015 Online Published: November 19, 2015 doi:10.5539/jpl.v8n4p9 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jpl.v8n4p9 Index 1. Introduction 31. Hawkins (1716-21) 2. Source Material 32. Blackstone (1765-9) 3. Legal Issues not Considered 33. Summary: Law to 1769 4. Meaning of Words 34. Foster (1776) 5. Benefit of Hindsight 35. East (1803) 6. Babylonian Code 36. Russell (1819) 7. Old Testament law 37. From 1819-1843 8. Roman law 38. Royal Commissions (1843-78) 9. Anglo-Saxon law 39. Stephen (1883) 10. Laws of Henry I (c.1113) 40. Kenny (1902) 11. Glanvill (c.1189) 41. Summary: Law to 1902 12. Summary: Law to 1189 42. Turner (1945) 13. Bracton (c.1240) 43. Royal Commission (1953) & Homicide Act 1957 14. Statute of Marlborough 1267 44. Smith & Hogan (1965) 15. Statute of Gloucester 1278 45. Criminal Law Revision Committee (1980) 16. Britton, Fleta & Mirror of Justices (c.1290) 46. Williams (1983) 17. Statute of Trespassers in Parks 1293 47. Law Commission Criminal Code (1989) 18. Edward III (1327-1377) 48. Carter & Harrison (1991) 19. Act of 1389 on Pardons 49. Justifiable Killing by 1998 20. From 1389-1551 50. -

Treason in Law, Treason Is the Crime That

Treason A 19th century illustration of Guy Fawkes by George Cruikshank. Guy Fawkes tried to assassinate James I of England. He failed and was convicted of treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a lesser superior was petty treason. A person who commits treason is known in law as a traitor. Oran's Dictionary of the Law (1983) defines treason as "...[a]...citizen's actions to help a foreign government overthrow, make war against, or seriously injure the [parent nation]." In many nations, it is also often considered treason to attempt or conspire to overthrow the government, even if no foreign country is aided or involved by such an endeavour. Outside legal spheres, the word "traitor" may also be used to describe a person who betrays (or is accused of betraying) their own political party, nation, family, friends, ethnic group, team, religion, social class, or other group to which they may belong. Often, such accusations are controversial and disputed, as the person may not identify with the group of which they are a member, or may otherwise disagree with the group leaders making the charge. See, for example, race traitor. At times, the term "traitor" has been levelled as a political epithet, regardless of any verifiable treasonable action.