Military and Strategic Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Hayim Katsman Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington [email protected]

CURRICULUM VITAE Hayim Katsman Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington [email protected] EDUCATION: • PhD., 2021 (expected) – University of Washington, Jackson School of International Studies. Dissertation title: “New Trends in Religious-nationalist politics in Israel/Palestine” Ph.D. Committee: Prof. Jim Wellman (chair), Prof. Joel Migdal, Prof. Liora Halperin, Prof. Christian Novetzke. • M.A., 2017 – Ben-Gurion University, Department of Politics and Government. Thesis subject: “Political Extremism in Israel: The case of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg and Religious-Zionism.” Advisors: Prof. Neve Gordon & Prof. Dani Filc. • B.A., 2014 – The Open University of Israel, Philosophy and Political Science. ACADEMIC TEACHING: 2019, Lecturer, JSIS 458: Israel: Politics and Society, University of Washington. 2019, Teaching assistant, HSTCMP 269: The Holocaust: History and Memory, University of Washington. 2014-2017, Teaching Assistant, Ben-Gurion University. Courses Taught: - Introduction to Political Philosophy - Israeli Politics - Introduction to International Relations (Israeli Air Force Academy) PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS Accepted: Hayim Katsman & Guy Ben-Porat, Israel: Religion and Political Parties. In Routledge Handbook of Religion and Political Parties, Ed. Jeff Haynes. (Routledge, 2019, Forthcoming). Hayim Katsman, Reactions Towards Jewish Radicalism: Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg and Religious Zionism. In Jewish Radicalisms, Ed. Frank Jacob & Sebestian Kunze (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019, Forthcoming). Articles under review: “Radicalism and violence in Religious-Zionist thought? The Case of Rabbi Yitzchak Ginzburg” BOOK REVIEWS Hayim Katsman, Review of Avi Sagi and Dov Schwartz, Religious Zionism and the Six-Day War: From Realism to Messianism; M. Hellinger et. al, Religious Zionism and the Settlement Project: Ideology, Politics, and Civil Disobedience. Israel studies review 34:2, pp. -

Sefer Haner on Mesechet Bava Kamma,Benefits

Sefer HaNer on Mesechet Bava Kamma Sefer HaNer on Mesechet Bava Kamma: A Review by:Rabbi Yosaif Mordechai Dubovick Not every important work written by a Rishon is blessed with popularity.[1] While many texts were available throughout the generations and utilized to their utmost; others were relegated to obscurity, being published as recently as this century, or even this year. Nearly a month doesn't pass without a "new" Rishon being made available to the public, and often enough in a critical edition. While each work must be evaluated on its own merit, as a whole, every commentary, every volume of Halachic rulings adds to our knowledge and Torah study.[2] From the Geonic era through the Rishonim, North Africa was blessed with flourishing Torah centers, Kairouan in Tunisia (800-1057),[3] Fostat (Old Cairo) in Egypt, and many smaller cities as well. Perhaps the crown jewel of "pre-Rambam" Torah study was the sefer Hilchot Alfasi by R' Yitchock Alfasi (the Rif).[4] Many Rishonim focused their novella around the study of Rif,[5] the Rambam taught Rif in lieu of Talmud,[6] and a pseudo-Rashi and Tosefot were developed to encompass the texts used and accompany its study.[7] In Aghmat, a little known city in Morocco, circa the Rambam's lifetime, rose up a little known Chacham whose work is invaluable in studying Rif, and by correlation, the Talmud Bavli as a whole. Yet, this Chacham was unheard of, for the most part, until the past half century. R' Zechariya b. Yehuda of Aghmat, authored a compendium of Geonim, Rishonim, and personal exegesis on Rif. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies Evolution of settlement typologies in rural Israel Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Keren Shalev November, 2016 “Human settlements are a product of their community. They are the most truthful expression of a community’s structure, its expectations, dreams and achievements. A settlement is but a symbol of the community and the essence of its creation. ”D. Bar Or” ~ III ~ תקציר למשבר הדיור בישראל השלכות מרחיקות לכת הן על המרחב העירוני והן על המרחב הכפרי אשר עובר תהליכי עיור מואצים בעשורים האחרונים. ישובים כפריים כגון קיבוצים ומושבים אשר התבססו בעבר בעיקר על חקלאות, מאבדים מאופיים הכפרי ומייחודם המקורי ומקבלים צביון עירוני יותר. נופי המרחב הכפרי הישראלי נעלמים ומפנים מקום לשכונות הרחבה פרבריות סמי- עירוניות, בעוד זהותה ודמותה הייחודית של ישראל הכפרית משתנה ללא היכר. תופעת העיור המואץ משפיעה לא רק על נופים כפריים, אלא במידה רבה גם על מרחבים עירוניים המפתחים שכונות פרבריות עם בתים צמודי קרקע על מנת להתחרות בכוח המשיכה של ישובים כפריים ולמשוך משפחות צעירות חזקות. כתוצאה מכך, סובלים המרחבים העירוניים, הסמי עירוניים והכפריים מאובדן המבנה והזהות המקוריים שלהם והשוני ביניהם הולך ומיטשטש. על אף שהנושא מעלה לא מעט סוגיות תכנוניות חשובות ונחקר רבות בעולם, מעט מאד מחקר נעשה בנושא בישראל. מחקר מקומי אשר בוחן את תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי דרך ההיסטוריה והתרבות המקומית ולוקח בחשבון את התנאים המקומיים המשתנים, מאפשר התבוננות ואבחנה מדויקים יותר על ההשלכות מרחיקות הלכת. על מנת להתגבר על הבסיס המחקרי הדל בנושא, המחקר הנוכחי החל בבניית בסיס נתונים רחב של 84 ישובים כפריים (קיבוצים, מושבים וישובים קהילתיים( ומצייר תמונה כללית על תהליכי העיור של המרחב הכפרי ומאפייניה. -

PM Netanyahu and Quartet Rep Blair Announce Economic Steps to Assist

Arabs, Jews to travel to Poland together Special delegation of Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christian students to visit concentration camps, learn about 'the other.' 'We're leaving as a united group of friends,' one student says Tomer Velmer A unique group consisting of 220 Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christians teenagers is expected to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland later this month. The participants are all students at Amal high schools across Israel. The trip will be held under the banner, "We are all part of same human fabric." Amal Group Director Shimon Cohen wrote a letter to the students, asking them to bring with them on their journey not just food and clothing but also patience, openness and attentiveness. The group decided to allow the students to experience both the suffering the Jewish people have gone through and the pain caused to other nations and religions in an attempt to acknowledge "the other". Preparing for the journey (Photo: Sami Kara) Many Amal schools are taking part in the special mission, including those in Shefaram, Rahat, Dimona, Hadera, Ofakim, and Kiryat Malakhi. Each student will pay roughly NIS 5,000 ($1,360) for the trip, part of which will be subsidized by Amal and the Education Ministry. Throughout their visit, the students will be divided into integrated groups consisting of Arab, Hebrew and English speakers. One big united group In preparation for their trip the students participated in a series of meetings aimed at connecting the different worlds they all come from. "The first few meetings were awkward for them due to cultural differences, and the fact that not all of them speak Hebrew," the project manager said. -

Enlightening Adventure in Israel Led by Rabbi Shira Joseph February/March 2022 with Optional Petra and Negev Extension (As of 7/19/21)

Congregation Sha’aray Shalom Enlightening Adventure in Israel Led by Rabbi Shira Joseph February/March 2022 with optional Petra and Negev Extension (as of 7/19/21) Israel is a land of connections and reconnections. It is a place that both holds nostalgia and awaits rediscovery. Over the decades, so much in Israel has changed dramatically, yet the essence that draws us remains the same. Traveling together as a community on Rabbi Joseph’s farewell tour, we will bond through our shared experiences and enhance our understanding of culture and archaeology, religion and politics, the ancient and the modern, as we delve in-depth into Israel’s millennia-old legacy as heart of the Jewish People. Day 1: Monday, February 21, 2022: DEPARTURE • We depart the United States on our overnight flight to Israel. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 2: Tuesday, February 22, 2022: WELCOME TO ISRAEL! • Shalom and Bruchim Habaim—welcome to Israel! Upon arrival, we are met by an Ayelet Tours representative and begin our adventure. • Ascend into the Judean Mountains and stop at Natan Rapoport’s Scroll of Fire sculpture in the Forest of the Martyrs. This dramatic sculpture commemorates Jewish history from the Holocaust through the founding of Israel through dramatic scenes of destruction and rebirth. • Upon entering Jerusalem, we stop at the Haas Promenade to say Shehecheyanu as we look out over the City of Gold. • We check into our hotel and join for a welcome dinner this evening. Overnight in Jerusalem ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Day 3: Wednesday, February 23, 2022: DIGGING INTO JERUSALEM • Breakfast at our hotel. • We visit Yad L’Kashish, the Lifeline for the Aged, an inspiring artisan workshop which empowers and supports hundreds of elderly and disabled Jerusalem residents. -

Strateg Ic a Ssessmen T

Strategic Assessment Assessment Strategic Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Volume 19 Volume The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | No. 4 No. Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | January 2017 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities Emily B. Landau and Ephraim Asculai Strategic ASSESSMENT Volume 19 | No. 4 | January 2017 Abstracts | 3 The Prime Minister and “Smart Power”: The Role of the Israeli Prime Minister in the 21st Century | 9 Yair Lapid The Israeli-Palestinian Political Process: Back to the Process Approach | 29 Udi Dekel and Emma Petrack Who’s Afraid of BDS? Economic and Academic Boycotts and the Threat to Israel | 43 Amit Efrati Israel’s Warming Ties with Regional Powers: Is Turkey Next? | 57 Ari Heistein Hezbollah as an Army | 67 Yiftah S. Shapir The Modi Government’s Policy on Israel: The Rhetoric and Reality of De-hyphenation | 79 Vinay Kaura India-Israel Relations: Perceptions and Prospects | 93 Manoj Kumar The Trump Effect in Eastern Europe: Heightened Risks of NATO-Russia Miscalculations | 103 Sarah Fainberg Negotiating Global Nuclear Disarmament: Between “Fairness” and Strategic Realities | 117 Emily B. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

A Tale of Four Cities

A Tale of Four Cities Dr. Shlomo Swirski Academic Director, Adva Center There are many ways of introducing one to a country, especially a country as complex as Israel. The following presentation is an attempt to do so by focusing on 4 Israeli cities (double Charles Dickens's classic book): Tel Aviv Jerusalem Nazareth Beer Sheba This will allow us to introduce some of the major national and ethnic groups in the country, as well as provide a glimpse into some of the major political and economic issues. Tel-Aviv WikiMedia Avidan, Gilad Photo: Tel-Aviv Zionism hails from Europe, mostly from its Eastern countries. Jews had arrived there in the middle ages from Germanic lands – called Ashkenaz in Hebrew. It was the intellectual child of the secular European enlightenment. Tel Aviv was the first city built by Zionists – in 1909 – growing out of the neighboring ancient, Arab port of Jaffa. It soon became the main point of entry into Palestine for Zionist immigrants. Together with neighboring cities, it lies at the center of the largest urban conglomeration in Israel (Gush Dan), with close to 4 million out of 9 million Israelis. The war of 1948 ended with Jaffa bereft of the large majority of its Palestinian population, and in time it was incorporated into Tel Aviv. The day-to-day Israeli- Palestinian confrontations are now distant (in Israeli terms) from Tel Aviv. Tel Aviv represents the glitzi face of Israel. Yet Tel Aviv has two faces: the largely well to do Ashkenazi middle and upper-middle class North, and the largely working class Mizrahi South (with a large concentration of migrant workers). -

A Hebrew Maiden, Yet Acting Alien

Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page i Reading Jewish Women Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page ii blank Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iii Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Reading Jewish Society Jewish Women IRIS PARUSH Translated by Saadya Sternberg Brandeis University Press Waltham, Massachusetts Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Parush’s Reading Jewish Women page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com © 2004 by Brandeis University Press Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or me- chanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. Originally published in Hebrew as Nashim Korot: Yitronah Shel Shuliyut by Am Oved Publishers Ltd., Tel Aviv, 2001. This book was published with the generous support of the Lucius N. Littauer Foundation, Inc., Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry through the support of the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment of Brandeis University, and the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute through the support of the Donna Sudarsky Memorial Fund. -

Jnf Blueprint Negev: 2009 Campaign Update

JNF BLUEPRINT NEGEV: 2009 CAMPAIGN UPDATE In the few years since its launch, great strides have been made in JNF’s Blueprint Negev campaign, an initiative to develop the Negev Desert in a sustainable manner and make it home to the next generation of Israel’s residents. In Be’er Sheva: More than $30 million has already been invested in a city that dates back to the time of Abraham. For years Be’er Sheva was an economically depressed and forgotten city. Enough of a difference has been made to date that private developers have taken notice and begun to invest their own money. New apartment buildings have risen, with terraces facing the riverbed that in the past would have looked away. A slew of single family homes have sprung up, and more are planned. Attracted by the River Walk, the biggest mall in Israel and the first “green” one in the country is Be’er Sheva River Park being built by The Lahav Group, a private enterprise, and will contribute to the city’s communal life and all segments of the population. The old Turkish city is undergoing a renaissance, with gaslights flanking the refurbished cobblestone streets and new restaurants, galleries and stores opening. This year, the municipality of Be’er Sheva is investing millions of dollars to renovate the Old City streets and support weekly cultural events and activities. And the Israeli government just announced nearly $40 million to the River Park over the next seven years. Serious headway has been made on the 1,700-acre Be’er Sheva River Park, a central park and waterfront district that is already transforming the city. -

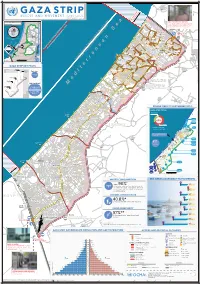

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n .