The North Etruscan Thesis of the Origin of the Runes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Germanic Heldenlied and the Poetic Edda: Speculations on Preliterary History

Oral Tradition, 19/1 (2004): 43-62 The Germanic Heldenlied and the Poetic Edda: Speculations on Preliterary History Edward R. Haymes One of the proudest inventions of German scholarship in the nineteenth century was the Heldenlied, the heroic song, which was seen by scholars as the main conduit of Germanic heroic legend from the Period of Migrations to the time of their being written down in the Middle Ages. The concept stems indirectly from the suggestions of several eighteenth-century Homeric scholars that since the Homeric poems were much too long to have been memorized and performed in oral tradition, they must have existed as shorter, episodic songs. Friedrich August Wolf’s well-known Prolegomena ad Homerum (1795) collected evidence for the idea that writing was not used for poetry until long after Homer’s time. He argued for a thorough recension of the poem under (or perhaps by) Pisistratus in the sixth century BCE as the first comprehensive written Homer. These ideas were almost immediately applied to the Middle High German Nibelungenlied by Karl Lachmann (1816), who was trained as a classical philologist and indeed continued to contribute in that area at the same time that he was one of the most influential members of the generation that founded the new discipline of Germanistik. On the basis of rough spots and contradictions (not only Homer nods!) Lachmann thought he could recognize twenty separate Lieder in the Middle High German epic. At the same time that Lachmann was deconstructing the German medieval epic, Elias Lönnrot was assembling the Finnish epic he called Kalevala from shorter songs in conscious imitation of the Homer (or Pisistratus) described by Wolf. -

Mythological Researcher and Author

From “Viktor Rydberg, En Lefnadsteckning” by Karl Warburg, 1900. Translated by William P. Reaves © 2003 pg. 472 Mythological Researcher and Author A coincidence that became quite fateful for Rydberg’s philosophical work as well as for his poetry, at the beginning of 1880s turned his attention to Nordic mythology, which quickly proceeded to capture his soul for nearly a decade. Rydberg’s mind had long been interested in Old Norse studies. One expression of this was his interest in rune research. It captivated him in two ways: because of its patriotic significance and its quality to offer up riddles to a mind inclined to them. By 1863, he had written an article in the Handelstidning about the Gisseberg Stone. During the 1870s, he occupied himself with the mysteries of rune-interpretation and corresponded, among other things, with the shrewd and independent-thinking researcher E. Jenssen about his interpretations of the Tanum, Stentoften, and Björketorp runestones, whose translations he made public partly in contribution to Götesborg’s and Bohuslän’s ancient monuments (the first installment), and partly in the Svenska Forneminnesföreningens tidskrift [―Journal of Swedish Ancient Monuments‖], 1875.1 The Nordic myths were dear to him since childhood –a passage from the Edda’s Völuspá, besides his catechism, had constituted his first oral-reading exam. During his years as a student he had sought to bring Saxo’s and the Edda’s information into harmony and he had followed the mythology’s development with interest, although he was very skeptical toward the philosophical and nature-symbolic interpretations that appeared here and there, not least in Grundtvigian circles. -

How Uniform Was the Old Norse Religion?

II. Old Norse Myth and Society HOW UNIFORM WAS THE OLD NORSE RELIGION? Stefan Brink ne often gets the impression from handbooks on Old Norse culture and religion that the pagan religion that was supposed to have been in Oexistence all over pre-Christian Scandinavia and Iceland was rather homogeneous. Due to the lack of written sources, it becomes difficult to say whether the ‘religion’ — or rather mythology, eschatology, and cult practice, which medieval sources refer to as forn siðr (‘ancient custom’) — changed over time. For obvious reasons, it is very difficult to identify a ‘pure’ Old Norse religion, uncorroded by Christianity since Scandinavia did not exist in a cultural vacuum.1 What we read in the handbooks is based almost entirely on Snorri Sturluson’s representation and interpretation in his Edda of the pre-Christian religion of Iceland, together with the ambiguous mythical and eschatological world we find represented in the Poetic Edda and in the filtered form Saxo Grammaticus presents in his Gesta Danorum. This stance is more or less presented without reflection in early scholarship, but the bias of the foundation is more readily acknowledged in more recent works.2 In the textual sources we find a considerable pantheon of gods and goddesses — Þórr, Óðinn, Freyr, Baldr, Loki, Njo3rðr, Týr, Heimdallr, Ullr, Bragi, Freyja, Frigg, Gefjon, Iðunn, et cetera — and euhemerized stories of how the gods acted and were characterized as individuals and as a collective. Since the sources are Old Icelandic (Saxo’s work appears to have been built on the same sources) one might assume that this religious world was purely Old 1 See the discussion in Gro Steinsland, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005). -

Hƒ›R's Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›Inn's

Hƒ›r’s Blindness and the Pledging of Ó›inn’s Eye: A Study of the Symbolic Value of the Eyes of Hƒ›r, Ó›inn and fiórr Annette Lassen The Arnamagnæan Institute, University of Copenhagen The idea of studying the symbolic value of eyes and blindness derives from my desire to reach an understanding of Hƒ›r’s mythological role. It goes without saying that in Old Norse literature a person’s physiognomy reveals his characteristics. It is, therefore, a priori not improbable that Hƒ›r’s blindness may reveal something about his mythological role. His blindness is, of course, not the only instance in the Eddas where eyes or blindness seem significant. The supreme god of the Old Norse pantheon, Ó›inn, is one-eyed, and fiórr is described as having particularly sharp eyes. Accordingly, I shall also devote attention in my paper to Ó›inn’s one-eyedness and fiórr’s sharp gaze. As far as I know, there exist a couple of studies of eyes in Old Norse literature by Riti Kroesen and Edith Marold. In their articles we find a great deal of useful examples of how eyes are used as a token of royalty and strength. Considering this symbolic value, it is clear that blindness cannot be, simply, a physical handicap. In the same way as emphasizing eyes connotes superiority 220 11th International Saga Conference 221 and strength, blindness may connote inferiority and weakness. When the eye symbolizes a person’s strength, blinding connotes the symbolic and literal removal of that strength. A medieval king suffering from a physical handicap could be a rex inutilis. -

In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia

Halls, Gods, and Giants: The Enigma of Gullveig in Óðinn’s Hall Tommy Kuusela Stockholm University Introduction The purpose of this article is to discuss and interpret the enig- matic figure of Gullveig. I will also present a new analysis of the first war in the world according to how it is described in Old Norse mythic traditions, or more specifically, how it is referred to in Vǫluspá. This examination fits into the general approach of my doctoral dissertation, where I try to look at interactions between gods and giants from the perspective of a hall environment, with special attention to descriptions in the eddic poems.1 The first hall encounter, depending on how one looks at the sources, is described as taking place in a primordial instant of sacred time, and occurs in Óðinn’s hall, where the gods spears and burns a female figure by the name of Gullveig. She is usually interpreted as Freyja and the act is generally considered to initiate a battle between two groups of gods – the Æsir and the Vanir. I do not agree with this interpretation, and will in the following argue that Gullveig should be understood as a giantess, and that the cruelty inflicted upon her leads to warfare between the gods (an alliance of Æsir and Vanir) and the giants (those who oppose the gods’ world order). The source that speaks most clearly about this early cosmic age and provides the best description is Vǫluspá, a poem that is generally considered to have been composed around 900– 1000 AD.2 How to cite this book chapter: Kuusela, T. -

Šiauliai University Faculty of Humanities Department of English Philology

ŠIAULIAI UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY RENDERING OF GERMANIC PROPER NAMES IN THE LITHUANIAN PRESS BACHELOR THESIS Research Adviser: Assist. L.Petrulion ė Student: Aist ė Andži ūtė Šiauliai, 2010 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................3 1. THE CONCEPTION OF PROPER NAMES.........................................................................5 1.2. The development of surnames.............................................................................................6 1.3. Proper names in Germanic languages .................................................................................8 1.3.1. Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic surnames.................................................9 1.3.2. Dutch surnames ..........................................................................................................12 1.3.3. English surnames........................................................................................................13 1.3.4. German surnames .......................................................................................................14 2. NON-LITHUANIAN SURNAMES ORTHOGRAPHY .....................................................16 2.1. The historical development of the problem.......................................................................16 2.2. The rules of transcriptions of non-Lithuanian proper names ............................................22 3. THE USAGE -

For the Official Published Version, See Lingua 133 (Sept. 2013), Pp. 73–83. Link

For the official published version, see Lingua 133 (Sept. 2013), pp. 73–83. Link: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00243841 External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance, D. Gary Miller, Oxford University Press (2012), xxxi + 317 pp., Price: £65.00, ISBN 9780199654260 Lexical borrowing aside, external influences are not the main concern of most histories of the English language. It is therefore timely, and novel, to have a history of English (albeit only up to the Renaissance period) that looks at English purely from the perspective of external influences. Miller assembles his book around five strands of influence: (1) Celtic, (2) Latin and Greek, (3) Scandinavian, (4) French, (5) later Latin and Greek input, and he focuses on influences that left their mark on contemporary mainstream English rather than on regional or international varieties. This review looks at all chapters, but priority is given to Miller’s discussions of structural influence, especially on English syntax, morphology and phonology, which often raise a number of theoretical issues. Loanwords from various sources, which are also covered extensively in the book, will receive slightly less attention. Chapter 1 introduces the Indo-European and Germanic background of English and gives short descriptions of the languages with which English came into contact. This is a good way to start the book, but the copious lists of loanwords from Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, German, Low German, Afrikaans etc., most of which appear in English long after the Renaissance stop-off point, were not central to its aims. It would have been better to use this space to expand upon the theoretical framework employed throughout the book. -

From Very Early Germanic and Before Towards the “Old” Stages of the Germanic Languages

F. Plank, Early Germanic 1 FROM VERY EARLY GERMANIC AND BEFORE TOWARDS THE “OLD” STAGES OF THE GERMANIC LANGUAGES 160,000+ years of human population history summarised, up to ca. 10,000 Before Now: Journey of Mankind: The Peopling of the World http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/journey/ The origin of Language and early languages – fascinating questions and challenges for geneticists, palaeontologists, archaeologists, physical and cultural anthropologists. Alas, this is not something historical linguists could do much/anything to shed light on. F. Plank, Early Germanic 2 No speech acts performed by early homines sapientes sapientes have come down to us to bear witness to their mental lexicons & grammars. From human fossils nothing can be inferred about the linguistic working of brains and little about the organs implicated in speech. Speech acts were given greater permanence through writing only much later: from around 3,200 BCE in Mesopotamia as well as in Egypt, from around 1,200 BCE in China, and from around 600 BCE in Mesoamerica. The technology for actually recording speech (and other) sounds was only invented in 1857. F. Plank, Early Germanic 3 What cannot be observed must be (rationally) hypothesised. The standard method in historical linguistics for rationally forming hypotheses about a past from which we have no direct evidence is the comparative method. Alas, the comparative method for the reconstruction of linguistic forms (lexical as well as grammatical) only reaches back some 8,000 years maximum, given the normal life expectancy and recognisability limits of forms and meanings. And it is questionable whether constructions can be rigorously reconstructed. -

The Case of Veneto and Verona

Dario Calomino Processing coin finds data in Northern Italy: the case of Veneto and Verona ICOMON e-Proceedings (Utrecht, 2008) 3(2009), 55 - 62 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org 55 Processing coin finds data in Northern Italy: the case of Veneto and Verona Dario Calomino Università degli Studi di Verona [email protected] The aim of this paper is to present the numismatic research of the Centro Regionale di Catalogazione dei Beni Numismatici del Veneto, a programme of cataloguing and processing coin finds and numismatic collections data in the region of Veneto, supervised by Prof. Giovanni Gorini of the University of Padua. The project takes place with the cooperation of both municipal and state museums, gathering together all the coins found in the region or belonging to historical collections. The coin finds are published in the multi-volume series of the Ritrovamenti monetali di età romana in Veneto, and the entire numismatic heritage of the museums of Veneto is catalogued in a numismatic computer database that will be available on the regional website. This paper offers some examples of the filing scheme for both the volumes and the database, illustrating research tools that can be used to find a specimen or to process data for further studies. Some results of these projects are also shown in the paper. The publication plan for coin finds and numismatic research in the town of Verona is also illustrated, in particular the forthcoming volume covering the coins found in the historical centre. Since 1986 the Centro Regionale di Catalogazione dei Beni Numismatici del Veneto (Regional Centre for Cataloguing the Numismatic Heritage in Veneto) has promoted a wide programme of cataloguing and processing data concerning coin finds in the region of Veneto, supervised by Prof. -

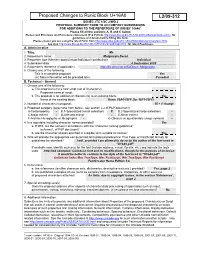

Proposed Additions Red = Proposed Changes Green = Other Possible Additions Black = Existing/Unchanged

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Ms 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: 4 September 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): http://ifa.amu.edu.pl/fa/Deron_Malgorzata 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: If needed B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): - Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic 16A0-16FF (for 16F1-16FF) 2. Number of characters in proposal: 15 + 1 change 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary - B.1-Specialized (small collection) X B.2-Specialized (large collection) - C-Major extinct - D-Attested extinct - E-Minor extinct - F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic - G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols - 4. -

Michael P. Barnes: What Is Runology?

What is runology and where does it stand today? Michael P. Barnes Introduction In recent years several scholars have presented critical examinations of the state of runology. They have offered varying views of the subject and suggested different ways forward. Most recently James Knirk sought funding for a project (Lesning og tolkning av runeinnskrifter: runologiens teori og metode „The reading and interpretation of runic inscriptions: the theory and method of runology‟) whose principal objectives were (i) to define runology as a subject or field of research, (ii) establish the theoretical (philological) basis for runological research, (iii) evaluate and develop the subject‟s methodological tools. The most important outcome of the project was to be a Handbook of Runology. Such a work would differ from previous introductions to the subject. Rather than offer a general survey of runes and runic inscriptions, it would lay down a methodological basis for the study of runic script and the examination, reading and interpretation of inscriptions. The study of runic writing in all its aspects is certainly in need of critical reappraisal. Those working with runes require at the very least (i) a definition of the subject, (ii) a state- ment of accepted methodological procedures, (iii) a series of constraints within which they can work. These matters are broached in the critical examinations of runology I mention above specifically: Claiborne Thompson‟s “On transcribing runic inscriptions” (1981); Terje Spurkland‟s “Runologi arkeologi, historie -

Rune-Magic, by Siegried Adolf Kummer 7/7/11 12:15 AM

Rune-Magic, by Siegried Adolf Kummer 7/7/11 12:15 AM [Home] [Home B] [Evolve] [Viva!] [Site Map] [Site Map A] [Site Map B] [Bulletin Board] [SPA] [Child of Fortune] [Search] [ABOL] RUNE-MAGIC by Siegfried Adolf Kummer, 1932 Translated and Edited by Edred Thorsson, Yrmin-Drighten, The Rune Gild © 1993 by Edred Thorsson Dedicated in Armanic Spirit to all my loyal Runers http://www.american-buddha.com/cult.runemagic.kummer.htm Page 1 of 64 Rune-Magic, by Siegried Adolf Kummer 7/7/11 12:15 AM Gods & Beasts -- The Nazis & the Occult, by Dusty Sklar The Story of the Volsungs, by Anonymous, translated by William Morris and Eirikr Magnusson Back Cover A Runic Classic Preserved Siegfried Adolf Kummer, along with Friedrich Bernhard Marby and Guido von List, was one of the great practical Runemasters of the early part of the 20th century. Rune-Magic preserves in a direct way the techniques and lore of the Armanen form of runology. Here the reader will learn some of the most original lore concerning such things as: Rune-Yoga Runic Hand-Signs (or mudras) Runic "Yodling" The Magical Formulation of the Grail-Chalice Keys to Runic Healing A Document of Historical Importance In this volume Thorsson preserves the text unaltered from its first appearance just a year before the National Socialists came to power in Germany. Sections of Rune-Magic will be found to be controversial by some, but Runa-Raven feels that for the sake of historical accuracy, and as a sign of respect for the intelligence of the reader, the text should stand as originally written in 1932.