A Comparative Analysis of Adults' Perceptions of Sense of Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS in the SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS of the SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA Ty Klaus Voelger a Thesis Submi

Cenozoic deposits in the southern foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson, Arizona Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Voelger, Klaus, 1926- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 10:53:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551218 CEMOZOIC DEPOSITS IN THE SOUTHERN FOOTHILLS OF THE SANTA CATALINA MOUNTAINS NEAR TUCSON, ARIZONA ty Klaus Voelger A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Geology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1953 Approved; , / 9S~J Director of Thesis ^5ate Univ. of Arizona Library The research on which this thesis is based was com pleted by Mr. Klaus Voelger of Berlin, Germany, while he was studying at the University of Arizona under the program of the Institute of International Education. The final draft was written after Mr. Voelgerf s return to his home in the Russian-occupied zone of Berlin. Difficulties such as a shortage of typing paper of uniform grade and the impossibility of adequate supervision and advice on matters of terminology, punctuation, and English usage account for certain details in which this thesis may depart from stand ards of the Graduate College of the University of Arizona. These details are largely mechanical, and it is felt that they do not detract appreciably from the quality of the research nor the clarity of presentation of the results. -

2006 Tumamoc Hill Management Plan

TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN September 2008 This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Parks Board UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Project Team Project University of Arizona Campus & Facilities Planning David Duffy, AICP, Director, retired Ed Galda, AICP, Campus Planner John T. Fey, Associate Director Susan Bartlett, retired Arizona State Museum John Madsen, Associate Curator of Archaeology Nancy Pearson, Research Specialist Nancy Odegaard, Chair, Historic Preservation Committee Paul Fish, Curator of Archaeology Suzanne Fish, Curator of Archaeology Todd Pitezel, Archaeologist College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture Brooks Jeffery, Associate Dean and Coordinator of Preservation Studies Tumamoc Hill Lynda C. Klasky, College of Science U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service Western Archaeological and Conservation Center Jeffery Burton, Archaeologist Consultant Team Cultural Affairs Office, Tohono O’odham Nation Peter Steere Joseph Joaquin September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN Cultural Resources Department, Gila River Indian Community Barnaby V. Lewis Pima County Cultural Resources and Historic Preservation Office Linda Mayro Project Team Project Loy C. Neff Tumamoc Hill Advisory Group, 1982 Gayle Hartmann Contributing Authors Jeffery Burton John Madsen Nancy Pearson R. Emerson Howell Henry Wallace Paul R. Fish Suzanne K. Fish Mathew Pailes Jan Bowers Julio Betancourt September 2008 UNIVERSI T Y OF ARIZONA TUMAMOC HILL CUL T URAL RESOURCES POLICY AND MANAGEMEN T PLAN This project was financed in part by a grant from the Historic Preservation Heritage Fund, which is funded by the Arizona Lottery and administered by the Arizona State Acknowledgments Parks Board. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Tumamoc Hill 2

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK, Theme XX: Arts and Science, Science and Invention NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) 0MB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ali entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Desert Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution and or common Tumamoc Hill 2. Location street & number Intersection of W. Anklam Road and W. St. Mary's Road not for publication city, town Tucson vicinity of state Arizona code 04 county code 019 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district xx public xx occupied agriculture museum yx building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress xx educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious Object in process xx yes: restricted government xx scientific being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name University of Arizona and Arizona State Lands Department (owns 340 acres) (owns 520 acres, leased to Univ. of AZ) street & number 1624 West Adams city, town Tucson, AZ 85721 vicinity of Phoenix state AZ 85007 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Pima County Courthouse street & number city, town Tucson state Arizona 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic American Buildings Surve^as tnis property been determined eligible? ——yes no date 1981 __ __________________—X- federal __ state __ county _ local depository for survey records Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. -

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas

Floristic Surveys of Saguaro National Park Protected Natural Areas William L. Halvorson and Brooke S. Gebow, editors Technical Report No. 68 United States Geological Survey Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona USGS Sonoran Desert Field Station The University of Arizona, Tucson The Sonoran Desert Field Station (SDFS) at The University of Arizona is a unit of the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (WERC). It was originally established as a National Park Service Cooperative Park Studies Unit (CPSU) in 1973 with a research staff and ties to The University of Arizona. Transferred to the USGS Biological Resources Division in 1996, the SDFS continues the CPSU mission of providing scientific data (1) to assist U.S. Department of Interior land management agencies within Arizona and (2) to foster cooperation among all parties overseeing sensitive natural and cultural resources in the region. It also is charged with making its data resources and researchers available to the interested public. Seventeen such field stations in California, Arizona, and Nevada carry out WERC’s work. The SDFS provides a multi-disciplinary approach to studies in natural and cultural sciences. Principal cooperators include the School of Renewable Natural Resources and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at The University of Arizona. Unit scientists also hold faculty or research associate appointments at the university. The Technical Report series distributes information relevant to high priority regional resource management needs. The series presents detailed accounts of study design, methods, results, and applications possibly not accommodated in the formal scientific literature. Technical Reports follow SDFS guidelines and are subject to peer review and editing. -

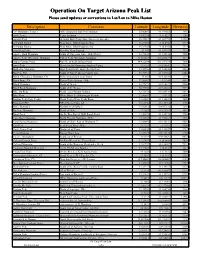

Peak List Please Send Updates Or Corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton

Operation On Target Arizona Peak List Please send updates or corrections to Lat/Lon to Mike Heaton Description Comment Latitude Longitude Elevation "A" Mountain (Tempe) ASU campus by Sun Devil Stadium 33.42801 -111.93565 1495 AAA Temp Temp Location 33.42234 -111.8227 1244 Agassiz Peak @ Snow Bowl Tram Stop (No access to peak) 35.32587 -111.67795 12353 Al Fulton Point 1 Near where SR260 tops the Rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Al Fulton Point 2 Near where SR260 tops the rim 34.29558 -110.8956 7513 Alta Mesa Peak For Alta Mesa Sign-up 33.905 -111.40933 7128 Apache Maid Mountain South of Stoneman Lake - Hike/Drive? 34.72588 -111.55128 7305 Apache Peak, Whetstone Mountain Tallest Peak, Whetstone Mountain 31.824583 -110.429517 7711 Aspen Canyon Point Rim W. of Kehl Springs Point 34.422204 -111.337874 7600 Aztec Peak Sierra Ancha Mountains South of Young 33.8123 -110.90541 7692 Battleship Mountain High Point visible above the Flat Iron 33.43936 -111.44836 5024 Big Pine Flat South of Four Peaks on County Line 33.74931 -111.37304 6040 Black (Chocolate) Mountain, CA Drive up and park, near Yuma 33.055 -114.82833 2119 Black Butte, CA East of Palm Springs - Hike 33.56167 -115.345 4458 Black Mountain North of Oracle 32.77899 -110.96319 5586 Black Rock Mountain South of St. George 36.77305 -113.80802 7373 Blue Jay Ridge North end of Mount Graham 32.75872 -110.03344 8033 Blue Vista White Mtns. S. of Hannagan Medow 33.56667 -109.35 8000 Browns Peak (Four Peaks) North Peak of Four Peaks Range 33.68567 -111.32633 7650 Brunckow Hill NE of Sierra Vista, AZ 31.61736 -110.15788 4470 Bryce Mountain Northwest of Safford 33.02012 -109.67232 7298 Buckeye Mountain North of Globe 33.4262 -110.75763 4693 Burnt Point On the Rim East of Milk Ranch Point 34.40895 -111.20478 7758 Camelback Mountain North Phoenix Mountain - Hike 33.51463 -111.96164 2703 Carol Spring Mountain North of Globe East of Highway 77 33.66064 -110.56151 6629 Carr Peak S. -

Downloaded and Reviewed on the State Parks’ Webpage Or Those Interested Could Request a Hard Copy

Governor of Arizona Janet Napolitano Arizona State Parks Board William Cordasco, Chair ting 50 ting 50 ra Y Arlan Colton ra Y b e b e a William C. Porter a le le r r e e s s William C. Scalzo C C Tracey Westerhausen Mark Winkleman 1957 - 2007 Reese Woodling 1957 - 2007 Elizabeth Stewart (2006) Arizona Outdoor Recreation Coordinating Commission Jeffrey Bell, Chair Mary Ellen Bittorf Garry Hays Rafael Payan William Schwind Duane Shroufe Kenneth E. Travous This publication was prepared under the authority of the Arizona State Parks Board. Prepared by the Statewide Planning Unit Resources Management Section Arizona State Parks 1300 West Washington Street Phoenix, Arizona 85007 (602) 542-4174 Fax: (602) 542-4180 www.azstateparks.com The preparation of this report was under the guidance from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, under the provisions of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 88-578, as amended). The Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, religion, national origin, age or disability. For additional information or to file a discrimination complaint, contact Director, Office of Equal Opportunity, Department of the Interior, Washington D.C. 20240. September 2007 ARIZONA 2008 SCORP ARIZONA 2008 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) Arizona State Parks September 2007 iii ARIZONA 2008 SCORP ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 2008 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) for Arizona was prepared by the Planning Unit, Resources Management -

Routing Opportunities Segment with Improvements to Existing Lines

J Oracle uan N B aw at au 77 Coronado N.F r ion ti D a st k l H a Pinal County San A a i D 79 r O s i t e Manuel z o S r A o i c 76 c n Oracle n e T z a ra a Junction n i N il c Saguaro/Tortolita a Graham County 266 T t r i o Coronado L a i n o l s a N.F R l o b le s W 10 To rt o l it a a s h Mountain BIOLOGICAL CORE Park Catalina MANAGEMENT Coronado AREAS Marana Park BIOLOGICAL CORE Marana MANAGEMENT Ironwood Avra Valley Butterfly AREAS National VRM I Rillito Park Monument Oro Mexican Rattlesnake spotted owl S Valley a n Linda P ed Vista ro SWAMP SPRINGS/HOT Coronado R Park i Cortaro v SPRINGS N.F WATERMAN e r WATERSHED ACEC MOUNTAINS Picture ACEC Rocks Gila chub 10 Wildwood Coronado N.F Avra Southwestern Park willow yon Ag Flowing Childrens Pima County an u flycatcher s C ir Wells Memorial ing re Hot Spr Wa Saguaro Silverbell Municipal Park sh ch National l V Golf u i Tucson Tanque o Park McCormick G p Course Wash u Verde e d d l li Juhan Park er W Sandario Tumamoc Hill Balboa ue V o a Park anq G sh Park T Menlo Tucson Willcox Park Linden Case DOS CABEZAS Park Twin Lakes Park PEAKS ACEC Starr South Tucson Tierra del Municipal Golf Course Tohono Tucson Estates Pa VRM I Pass Golf Club Sol Park nt Indian an Saguaro o 186 Res. -

Thesis and Dissertation Index of Arizona Geology to December 1979

Arizona Geological Society Digest, Volume XII, 1980 261 Thesis and Dissertation Index of Arizona Geology to December 1979 From The University of Arizona, Arizona State University, and Northern Arizona University compiled by 1 Gregory R. Wessel Introduction This list is a compilation of all graduate theses and dissertations completed at The University of Arizona, Arizona State University, and Northern Arizona University concerning the geology of Arizona. The list is complete through December 1979. To facilitate the use of this list as a reference, papers are arranged alphabetically into five sec tions on the basis of study area. Four sections cover the four quadrants of the state of Arizona us ing the Gila and Salt River Meridian and Base Line (Fig. 1), and the fifth section contains theses that pertain to the entire state. A thesis or dissertation that includes work in two quadrants is listed under both sections. Those covering subjects or areas outside of the geology of Arizona are omitted. This list was compiled from tabulations of geology theses graciously supplied by each university. Although care was taken to include all theses, some may have been inadvertently overlooked. It is hoped that readers will report any omissions so they may be included in Digest XIII. Digest XIII will contain an update of work 114 113 112 III 110 I 9 completed at Arizona universities, as well as a 37 list of theses and dissertations on Arizona geol ogy completed at universities outside of the state. Grateful acknowledgment is made of the assist 36 ance of Tom L. Heidrick, who inspired the pro- N£ ject and who, with Joe Wilkins, Jr. -

Mid-Tertiary Magamtism in Southeastern Arizona M

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/29 Mid-Tertiary magamtism in southeastern Arizona M. Shafiqullah, P. E. Damon, D. J. Lynch, P. H. Kuck, and W. A. Rehrig, 1978, pp. 231-241 in: Land of Cochise (Southeastern Arizona), Callender, J. F.; Wilt, J.; Clemons, R. E.; James, H. L.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 29th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 348 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1978 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. -

Research Program, Geochronology Laboratories, University of Arizona

RESEARCH PROGRflM, GEOCHRONOLO GY LABORATORIES UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA By Terah L. fuiley Geochronology Laboratories, University of Arizona Geological sciences have been primarily concerned with three dimensional methodology in the study of the earth and its history; the fourth dimension, time, has been generally considered in a relative manner only. Allied sciences are adding a more definite time scale with which geologic phenomena can be correlated. The Geochronology Laborat ories employ, or will employ shortly, many of the major "dating" methods developed by these allied sciences in attempts to supply a sharper focus on this fourth dimension. The methods used range from stratigraphic and paleontologic techniques, whereby events are merely placed in their correct relative position or sequence, to techniques in geochemistry and dendrochronology, whereby events are "dated" in terms of years. Research facilities available, plus those being planned and assembled, enable the Laboratories' personnel to study many varieties of temporal problems in historical field exercises. The Geochronology Laboratories have their office, research library, paleontological, and palynological sections on Tumamoc Hill in buildings originally constructed and used by the Carnegi e Institution for a desert laboratory. These buildings have been made available to the University by the Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiement Station, United States Department of Agriculture. The geo chemical section of the Laboratories, including the Carbon 14 Age Determination Laboratory, are housed in the Geology Building on the University campus. The dendrochronological research is carried on in cooperation with the Laboratory of Tree.Ring Research, also housed on the campus. Research projects in the Laboratories are interdisciplinary and interdepart mental, the extent being dependent on the nature of the research. -

National Park Service

Abstract Between June 24 and 28, 2019, archaeologists with National Park Service’s (NPS) Intermountain Region Archaeology Program (IMRAP) and Southern Arizona Support Office (SOAR) conducted a systematic pedestrian survey of 18.2 km (11.3 mi) of the southern boundary of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (ORPI), a portion of the 3,201 km (1,989 mi) long international border between the United States and Mexico. Over the course of this five-day-long field project the archaeologists surveyed a total of 45.3 ha (112 ac). Cumulatively, they identified, recorded, and mapped 35 isolated occurrences, 20 isolated features, and 5 archaeological sites. This report 1) summarizes the survey findings and 2) offers National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) eligibility recommendations for the 5 newly identified archaeological sites. i Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................... v I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Environmental Setting ..............................................................................................................