Rothbury Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantastic W Ays to Travel and Save Money with Go North East Travelling with Uscouldn't Be Simpler! Ten Services Betw Een

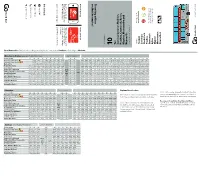

money with Go North East money and save travel to ways Fantastic couldn’t be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling gonortheast.co.uk the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East Get in touch gonortheast.co.uk 420 5050 0191 @gonortheast simplyGNE 5 mins 5 mins gonortheast.co.uk /gneapp Buses run up to Buses run up to 30 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety gonortheast.co.uk smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key Serving: Hexham Corbridge Stocksfield Prudhoe Crawcrook Ryton Blaydon Metrocentre Newcastle Go North East 10 Bus times from 21 May 2017 21 May Bus times from Ten Ten Hexham, between Services Ryton, Crawcrook, Prudhoe, and Metrocentre Blaydon, Newcastle 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Crawcrook » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 30 minutes at Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10X 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle Eldon Square - 0623 0645 0715 0745 0815 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1355 1425 1455 1527 1559 1635 1707 1724 1740 1810 1840 1900 1934 1958 2100 2200 2300 Newcastle Central Station - 0628 0651 0721 0751 0821 0901 0931 1001 31 01 1401 1431 1501 1533 1606 1642 1714 1731 1747 1817 1846 1906 1940 2003 2105 2205 2305 Metrocentre - 0638 0703 0733 0803 0833 0913 0944 1014 44 14 1414 1444 1514 1546 1619 1655 1727 X 1800 1829 1858 1919 1952 2016 2118 2218 2318 Blaydon -

Gateway West Local Amenities

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/03064/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr Daniel Kemp Agent: Mr Adam Barrass Keepwick Farm, Humshaugh, 16/17 Castle Bank, Tow Law, Hexham, Bishop Auckland, DL13 4AE, Proposal: Proposal for the construction of a four bedroomed agricultural workers dwelling adjacent to existing agricultural building Location: Land North West Of Carterway Heads, Carterway Heads, Northumberland Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. 9, 2019 Expiry Date: Nov. 3, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Melanie Francis Decision Level: Ward: South Tynedale Parish: Shotley Low Quarter Application No: 19/03769/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr & Mrs Glenn Holliday Agent: Earle Hall 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ridley House, Ridley Avenue, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Blyth, Northumberland, NE24 3BB, Proposal: Proposed dining room extension; garden room; rooms in roof space with dormer windows Location: 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. -

Elyvale High Street, Rothbury Guide Price £250,000

Elyvale High Street, Rothbury Guide Price £250,000 A traditional 2-storey stone-built cottage in the centre of Rothbury within easy walking distance of all services and amenities. The property requires a degree of modernisation but oers spacious accommodation. On the Ground Floor; Entrance Lobby, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Kitchen and WC. On the First Floor; 3 Bedrooms (two doubles) and Bathroom. At the rear of the property there is parking and also stone steps to a agged seated patio area. turvey www.turveywestgarth.co.uk westgarth t: 01669 621312 land & property consultants Known as the ‘Capital of Coquetdale’ Rothbury is a small Northumbrian market town equidistant from the larger settlements of Alnwick and Morpeth. It still shows signs of prosperity as a late Victorian resort, brought about by the arrival of the railway, (now Middle Schools, a library, art centre, a number of public houses/restaurants, banks, golf club, new cottage hospital, professional services and a full range of local shops. Location Please refer to the location plan incorporated within these particulars. Services Mains water, drainage, electricity and gas. For detailed directions please contact Gas fired central heating. Secondary glazing and some the selling Agents. double glazing throughtout. Particulars prepared MArch 2016 Postcode Property Reference 10245 NE65 7UA Local Authority Northumberland County Council Tel: 01670 627000 Council Tax The property is in Council Tax Band D (£1,587.73 2014/15) Tenure Freehold with vacant possession. Viewing Strictly by appointment with the selling agents. EPC EPC Rating E (44) (full report upon request). turvey westgarth land & property consultants Ground Floor First Floor Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2014. -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report. -

Leyland Cottage, Garleigh Road Rothbury, Northumberland, NE65 7RB O.I.R.O £199,950

Leyland Cottage, Garleigh Road Rothbury, Northumberland, NE65 7RB O.I.R.O £199,950 Ref: W16a www.aitchisons.co We are delighted to offer for sale this detached cooker. Central heating radiator. Door to rear hall. three bedroom bungalow, which is located in an Rear Hall elevated position with superb views over Rothbury 9'11 x 4'5 (3.02m x 1.35m) and the surrounding countryside. The property is Glazed entrance door to the front of the bungalow, in need of modernisation and upgrading, however, a window to the side and a cloaks hanging area. it offers tremendous potential to create a lovely home. Leyland Cottage has the benefits of double Bedroom 1 glazing and gas central heating, 'off road' parking, 12'6 x 13'2 (3.81m x 4.01m) a garage, generous gardens to the front and rear A double bedroom with a double window to the and well proportioned living accommodation. rear. Central heating radiator. The bright interior comprises of a living room, Bedroom 2/Dining Room kitchen, three bedrooms, two of which are double, 14'4 x 11'6 (4.37m x 3.51m) a kitchen and a bathroom. A double bedroom which could be used as Rothbury is a beautiful Northumberland town, with another reception room if required. The room has an excellent range of amenities and facilities, a double window to the front and a central heating including varied shopping, cafés, restaurants, a radiator. tennis club, golf club and the famous Cragside House and gardens. Rothbury is conveniently Bedroom 3 located close to Alnwick (12 miles), Morpeth (15 13' x 7' (3.96m x 2.13m) miles) and Newcastle (29 miles). -

Northumberland County Council

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/01367/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 7, 2019 Applicant: Mr Philip Mellen-Steele Agent: 9 Queen Street, Alnwick, Northumberland, NE66 1RD, Proposal: Proposed rear ground floor extension to enlarge kitchen, utility and living-room; front elevation bay window at first floor over existing; widen driveway and canopy over garage door Location: 11 Lesbury Road, Lesbury, Northumberland, NE66 3ND Neighbour Expiry Date: May 7, 2019 Expiry Date: July 1, 2019 Case Officer: Mrs Esther Ross Decision Level: Ward: Alnwick Parish: Lesbury Application No: 19/01466/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Mrs Rachel Towns Agent: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Proposal: Proposed new single storey garage in addition to previously approved scheme. Location: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Neighbour Expiry Date: May 8, 2019 Expiry Date: July 2, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Marie Haworth Decision Level: Ward: Stocksfield And Broomhaugh Parish: Stocksfield Application No: 19/00999/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Conchie Agent: Half Acres, Catton, Hexham, Northumberland, NE47 9LH, Proposal: 1) Retrospective permission for 14no. -

Otterburn Ranges the Roman Road of Dere Street 3 50K Challenge 4 the Eastern Boundary Is Part of a Fine Route for Cyclists

The Otterburn Ranges The Roman road of Dere Street 3 50K Challenge 4 The Eastern Boundary is part of a fine route for cyclists. This circular cycle route takes you from Alwinton A challenging walk over rough terrain requiring navigation through the remote beauty of Coquetdale to the Roman skills, with one long stretch of military road. Rewards camps at Chew Green and then back along the upland with views over the River Coquet and Simonside. spine of the military training area. (50km / 31 miles) Distance 17.5km (11 miles) Start: The National Park car park at Alwinton. Start: Park at the lay-by by Ovenstone Plantation. Turn right to follow the road up the Coquet Valley 20km After the gate join the wall NW for 500m until the Controlled to Chew Green. wood. Go through the gate for 500m through the wood, Continue SE from Chew Green on Dere Street for 3km keeping parallel to the wall. to junction of military roads – go left, continue 2.5km After the wood follow the waymarked path N for 1km ACCESS AREA then take the road left 2.5km to Ridlees Cairn. After up to forest below The Beacon.This will be hard going! 1km keep left. After 3.5km turn left again to follow the Follow path 1km around the forest which climbs to The This area of the Otterburn Ranges offers a variety of routes ‘Burma Road’ for 10km to descend through Holystone Beacon (301m). From here the way is clear along the across one of the remotest parts of Northumberland. -

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland

Songs of the Sea in Northumberland Destinations: Northumberland & England Trip code: ALMNS HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Sea shanties were working songs which helped sailors move in unison on manual tasks like hauling the anchor or hoisting sails; they also served to raise spirits. Songs were usually led by a shantyman who sang the verses with the sailors joining in for the chorus. Taking inspiration from these traditional songs, as well as those with a modern nautical connection, this break allows you to lend your voice to create beautiful harmonies singing as part of a group. Join us to sing with a tidal rhythm and flow and experience the joy of singing in unison. With a beachside location in sight of the sea, we might even take our singing outside to see what the mermaids think! WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality Full Board en-suite accommodation and excellent food in our Country House • Guidance and tuition from a qualified leader, to ensure you get the most from your holiday • All music HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Relaxed informal sessions • An expert leader to help you get the most out of your voice! • Free time in the afternoons www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 ACCOMMODATION Nether Grange Sitting pretty in the centre of the quiet harbour village of Alnmouth, Nether Grange stands in an area rich in natural beauty and historic gravitas. There are moving views of the dramatic North Sea coastline from the house too. This one-time 18th century granary was first converted into a large family home for the High Sheriff of Northumberland in the 19th century and then reimagined as a characterful hikers’ hotel. -

Holystone Augustinian Priory and Church of St Mary the Virgin, Northumberland

HOLYSTONE AUGUSTINIAN PRIORY AND CHURCH OF ST MARY THE VIRGIN, NORTHUMBERLAND Report on an Archaeological Excavation carried out in March 2015 By Richard Carlton The Archaeological Practice/University of Newcastle [[email protected]] CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. EXCAVATION 3. CONCLUSIONS 4. REFERENCES APPENDIX 1: Lapidary Material from Holystone Priory Excavations in March 2015. APPENDIX 2: A Recently-Discovered Cross Slab from Holystone. APPENDIX 3: Medieval Grave Stone on the north side of the chancel of the parish church. ILLUSTRATIONS Illus. 01: Extract from a plan of Farquhar’s Estate, Holystone by James Robertson, December 1765 (PRO MPI 242 NRO 6247-1). Illus. 02: The Church of St Mary shown on the Holystone Tithe plan of 1842. Illus. 03: The Church of St Mary shown on the 1st edition Ordnance Survey Plan, surveyed c.1855. Illus. 04: 19th century view of the church partly obscured by thatched cottages to the south. Illus. 05: Collier’s photograph of the church in the 1930s. Illus. 06: The Church of St Mary shown on a 1920s edition of the Ordnance Survey Plan. Illus. 07: The Church of St Mary shown on a 1970s edition of the Ordnance Survey Plan. Illus. 08: Honeyman’s Plan of the Church of St Mary based on fieldwork in the 1930s Illus. 09: Holystone medieval grave covers – top three built into the south side of the church; bottom left excavated from the graveyard in 2004; bottom right built into Holystone Mill. Illus. 10: Survey of the excavation site with trench locations marked on the south side of the church. -

Walk to Wellbeing 2011

PleaSe nOte: Walk to Wellbeing What is it ? a walk to wellbeing is: • the walks and shared transport are A programme of 19 walks specially • free free selected by experienced health walk • sociable & fun • each walk has details about the leaders to introduce you to the superb • something most people can easily do terrain to help you decide how landscape that makes Northumberland • situated in some of the most suitable it is for you. the full route National Park so special. inspirational and tranquil landscape in Walk to Wellbeing 2011 England can be viewed on Walk4life Is it for me? Get out and get healthy in northumberland national Park website If you already join health walks and would • Refreshments are not provided as like to try walking a bit further in beautiful Some useful websites: part of the walk. countryside - Yes! To find out the latest news from • Meeting points along Hadrian’s Wall If you’ve never been on a health walk but Northumberland National Park: can be easily reached using the would like to try walking in a group, with a www.northumberlandnationalpark.org.uk leader who has chosen a route of around Hadrian’s Wall Bus (free with an For more information on your local over 60 pass) 4 miles which is not too challenging and full of interest -Yes! Walking For Health • Please wear clothing and footwear group:www.wfh.naturalengland.org.uk (preferably boots with a good grip) Regular walking can: For more information on West Tynedale appropriate for changeable weather • help weight management Healthy Life Scheme and other healthy and possible muddy conditions. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland