Labour Mobility in the Small-Scale Fisheries Sector of Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Covid 19 Coastal Plan- Trivandrum

COVID-19 -COASTAL PLAN Management of COVID-19 in Coastal Zones of Trivandrum Department of Health and Family Welfare Government of Kerala July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS THIRUVANANTHAPURAMBASIC FACTS .................................. 3 COVID-19 – WHERE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM STANDS (AS ON 16TH JULY 2020) ........................................................ 4 Ward-Wise maps ................................................................... 5 INTERVENTION PLANZONAL STRATEGIES ............................. 7 ANNEXURE 1HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE - GOVT ................. 20 ANNEXURE 2HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE – PRIVATE ........... 26 ANNEXURE 3CFLTC DETAILS................................................ 31 ANNEXURE 4HEALTH POSTS – COVID AND NON-COVID MANAGEMENT ...................................................................... 31 ANNEXURE 5MATERIAL AND SUPPLIES ............................... 47 ANNEXURE 6HR MANAGEMENT ............................................ 50 ANNEXURE 7EXPERT HEALTH TEAM VISIT .......................... 56 ANNEXURE 8HEALTH DIRECTORY ........................................ 58 2 I. THIRUVANANTHAPURAM BASIC FACTS Thiruvananthapuram, formerly Trivandrum, is the capital of Kerala, located on the west coastline of India along the Arabian Sea. It is the most populous city in India with the population of 957,730 as of 2011.Thiruvananthapuram was named the best Kerala city to live in, by a field survey conducted by The Times of India.Thiruvananthapuram is a major tourist centre, known for the Padmanabhaswamy Temple, the beaches of -

Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum

LATIN ARCHDIOCESE OF TRIVANDRUM His Grace, Most Rev. Dr. M. Soosa Pakiam L.S.S.S., Thl. Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 11.03.1946 Date of Ordination : 20.12.1969 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 02.02.1990 Metropolitan Archbishop of Trivandrum: 17.06.2004 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org 1 His Excellency, Most Rev. Dr. Christudas Rajappan Auxiliary Bishop of Trivandrum Date of Birth : 25.11.1971 Date of Ordination : 25.11.1998 Date of Episcopal Ordination : 03.04.2016 Latin Archbishop's House Vellayambalam, P.B. No. 805 Trivandrum, Kerala, India - 695 003 Phone : 0471 / 2724001 Fax : 0471 / 2725001 Mobile : 8281012253, 8714238874, E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Website : www.latinarchdiocesetrivandrum.org (Dates below the address are Dates of Birth (B) and Ordination (O)) 2 1. Very Rev. Msgr. Dr. C. Joseph, B.D., D.C.L. Vicar General & Chancellor PRO & Spokesperson Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003, Kerala, India T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001; Mobile: 9868100304 Email: [email protected], [email protected] B: 14.04.1949 / O: 22.12.1973 2. Very Rev. Fr. Jose G., MCL Judicial Vicar, Metropolitan Archdiocesan Tribunal & Chairman, Archdiocesan Arbitration and Conciliation Forum Latin Archbishop's House, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum T: 0471-2724001; Fax: 0471-2725001 & Parish Priest, St. Theresa of Lisieux Church, Archbishop's House Compound, Vellayambalam, Trivandrum - 695 003 T: 0471-2314060 , Office ; 0471-2315060 ; C: 0471- 2316734 Web: www.vellayambalamparish.org Mobile: 9446747887 Email: [email protected] B: 06.06.1969 / O: 07.01.1998 3. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Thiruvananthapuram Rural District from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Thiruvananthapuram Rural district from 17.01.2021 to 23.01.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 125/2021 U/s Sec. 4(2)(e)(j) of Kerala Epidemic ATTINGAL MOOLAYIL 23-01-2021 Diseases (THIRUVA 20, KATCHERY Sanooj S, S I BAILED BY 1 ARAVIND UTHAMAN KATTAKKALIL at 23:00 Ordinance NANTHAP Male JUNCTION Of Police POLICE VEEDU, AYILAM Hrs 2020 & Sec. URAM 3(a) of RURAL) COVID-19 Additional Regulation G PALODE MURALEED TC 17/1361, 23-01-2021 140/2021 U/s (THIRUVA 58, HARAN BAILED BY 2 JOSE SIYAS DAS POOJAPPURA, ILAVATTOM at 22:05 279 IPC & 185 NANTHAP Male PILLAI, SI OF POLICE TVM Hrs MV ACT URAM POLICE, RURAL) PALODE PS BIJEESH BHAVAN MARANAL ELAKONAM LOOR 23-01-2021 134/2021 U/s HARIKUMA 32, VAZHICHAL THOONGAM (THIRUVA SANTHOSH BAILED BY 3 VISHNU at 21:00 U/S 15(C) OF AR Male OTTASEKHARAM PARA NANTHAP KUMAR.S POLICE Hrs ABKARI ACT ANGALAM URAM VILLAGE RURAL) KAMALA MARANAL BHAVAN LOOR 23-01-2021 134/2021 U/s KANNANM MOHANDA 27, PEREKKONAM THOONGAM (THIRUVA SANTHOSH BAILED BY 4 at 21:00 U/S 15(C) OF OHAN S Male VAZHICHAL PARA NANTHAP KUMAR.S POLICE Hrs ABKARI ACT OTTASEKHARAM URAM ANGALAM RURAL) 150/2021 U/s 269 IPC & VENJARAM Sec. -

Cyclone Ockhi

Public Inquest Team Members 1. Justice B.G. Kholse Patil Former Judge, Maharashtra High Court 2. Dr. Ramathal Former Chairperson, Tamil Nadu State Commission for Women 3. Prof. Dr. Shiv Vishvanathan Professor, Jindal Law School, O.P. Jindal University 4. Ms. Saba Naqvi Senior Journalist, New Delhi 5. Dr. Parivelan Associate Professor, School of Law, Rights and Constitutional Governance, TISS Mumbai 6. Mr. D.J. Ravindran Formerly with OHCHR & Director of Human Rights Division in UN Peace Keeping Missions in East Timor, Secretary of the UN International Inquiry Commission on East Timor, Libya, Sudan & Cambodia 7. Dr. Paul Newman Department of Political Science, University of Bangalore 8. Prof. Dr. L.S. Ghandi Doss Professor Emeritus, Central University, Gulbarga 9. Dr. K. Sekhar Registrar, NIMHANS Bangalore 10. Prof. Dr. Ramu Manivannan Department of Political Science, University of Madras 11. Mr. Nanchil Kumaran IPS (Retd) Tamil Nadu Police 12. Dr. Suresh Mariaselvam Former UNDP Official 13. Prof. Dr. Fatima Babu St. Mary’s College, Tuticorin 14. Mr. John Samuel Former Head of Global Program on Democratic Governance Assessment - United Nations Development Program & Former International Director - ActionAid. Acknowledgement Preliminary Fact-Finding Team Members: 1. S. Mohan, People’s Watch 2. G. Ganesan, People’s Watch 3. I. Aseervatham, Citizens for Human Rights Movement 4. R. Chokku, People’s Watch 5. Saravana Bavan, Care-T 6. Adv. A. Nagendran, People’s Watch 7. S.P. Madasamy, People’s Watch 8. S. Palanisamy, People’s Watch 9. G. Perumal, People’s Watch 10. K.P. Senthilraja, People’s Watch 11. C. Isakkimuthu, Citizens for Human Rights Movement 12. -

Kowdiar Boys' Home

KOWDIAR BOYS’ HOME THE SALVATION ARMY:INDIA SOUTH WESTERN TERRITORY Kowdiar Boys’ Home is located in the prime area of Trivandrum City, Kerala State of India. This Boys Home started in the early period of 1970’s and shifted to three buildings. Many boys lived here and got good life. One of our old inhabitants became a doctor later. At present we have 25 boys. Children playing cricket and soccer games le The Salvation Army Boys Home Kowdiar – Details of Inhabitants Year of Date of No Name Joining Birth Class Parents Address Reason Religion Chandran & Sarath Bhavan, Anthiyoorkonam, Onamcodu, Father is a labour, 1 Sarathchand B 2013 22.05.1997 12 Baby Poovachal No income Hindu G.S. Nair & Father left, mother 2 Githin G S 2013 01.04.2000 10 Sindhu G.S Bhavan, Venkavila, Iruchiyam, NDD daily wages worker Hindu Raj & Father left, No 3 Saran P. Raj 2013 30.10.1999 10 Santhamma P K Plallikizhakethil, Kidangannur, PTA income Hindu Vishak P K & Alice Bhavan, Kudumpannoor, Father Expired, 4 Naveen V.R 2013 18.06.1998 10 Rema S Pravachambalam, TVM Mother sales girl Hindu Christhudas & Father expired, 5 Binu C 2013 23.12.1999 9 Selvi Errikilavila veedu, Pozhiyoor, Poovar, TVM Very poor Christian Baby & Raji Bhavan, Pulimudu, Mangadu Kulappada Father drunkard, 6 Gokul R.B 2013 05.08.1998 9 Rajesh C S PO, Arynadu Poverty Hindu Baby & Raji Bhavan, Pulimudu, Mangadu Kulappada Father drunkard, 7 Amal R.B 2013 19.04.2000 9 Rajesh C S PO, Arynadu Poverty Hindu Rajan Mannamkonam, Thadatharikathu, Father left, 8 Shibin S 2013 18.03.2000 9 & Sheeja Uzhamalachal, Kulappakada Poverty Hindu Mabel & Father fishing, no 9 Manoj S 2013 05.01.2000 9 Shilavadima Puthuval purayidam, Pozhiyoor, Poovar income, poor Christian Sajeeve & Aswathy Bhavan, Asramam road, Punnakadu, Mother expired, no 10 Athul Sajeev 2013 15.06.2000 9 Sujatha TVM. -

Existence and Survey of Medicinal Plants Along the Neerody Coastal Line of Kanniyakumari District S

|| Volume 4 || Special Issue 10 || ICCEME 2019-2020 || ISSN (Online) 2456-0774 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH AND ENGINEERING TRENDS Existence and Survey of Medicinal Plants along The Neerody Coastal Line Of Kanniyakumari District S. Jaya Kumar 1, P. Rama Devi 2* and S.Rejitha Nesamony Memorial Christian College, Marthandam, Kanyakumari - 629 165, Tamil Nadu, India1 2 Aditanar College of Arts and Science, Tiruchendur - 628 216, Tamil Nadu, India p. [email protected], Mobile : +91-9677509294 Abstract- Present Study was conducted in the Neerody methods date back to 5000 B.C. The coastal population of the coastal Villages of Kanniyakumari district, Tamil Nadu, country has their own herbal homework to treat various India to document the Medicinal plant wealth. diseases. The use of herbal medicines by coastal communities is Taxonomically, a total of 32 plant species belonging to 31 inclined by distinct socio-cultural practices, support of genera and 23 families were recorded. Of these 15 (50%) traditional ability and services of traditional medicine. These were herbs, 5 (16%) were shrubs, and 11 (34%) were trees. people have much associated with their ambient environment The plant parts used for the preparation of medicine, whole and ecology and mainly depend on it for primary health care plants were found to be most frequently used for the system, because of they live in remote areas as compared to preparation of remedies. The mode of preparations is paste, modern facilities. juice, decoction and powder. The medicinal plants of the India has a coastline of about 7516.6 km long with study area have been used to treat 53 illnesses. -

Trivandrum District, Kerala State

TECHNICAL REPORTS: SERIES ‘D’ CONSERVE WATER – SAVE LIFE भारत सरकार GOVERNMENT OF INDIA जल संसाधन मंत्रालय MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES कᴂ द्रीय भजू ल बो셍 ड CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD केरल क्षेत्र KERALA REGION भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका, त्रिवᴂद्रम स्ज쥍ला, केरल रा煍य GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF TRIVANDRUM DISTRICT, KERALA STATE तत셁वनंतपुरम Thiruvananthapuram December 2013 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET OF TRIVANDRUM DISTRICT, KERALA रानी वी आर वैज्ञातनक ग Rani V.R. Scientist C KERALA REGION BHUJAL BHAVAN KEDARAM, KESAVADASAPURAM NH-IV, FARIDABAD THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 004 HARYANA- 121 001 TEL: 0471-2442175 TEL: 0129-12419075 FAX: 0471-2442191 FAX: 0129-2142524 GROUNDWATER INFORMATION BOOKLET TRIVANDRUM DISTRICT, KERALA Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 RAINFALL AND CLIMATE ........................................................................................... 3 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL TYPES ................................................................... 5 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO...................................................................................... 6 5.0 GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ................................................. 12 6.0 GROUNDWATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ................................. 15 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ................................................................. 15 8.0 -

AVM Canal Poovar to Erayumanthurai (11.30Km)

Final Feasibility Report National Waterway-13, Region VI - AVM Canal Poovar to Erayumanthurai (11.30km) SURVEY PERIOD: 20 DEC 2015 TO 18 FEB 2016 Volume - I Prepared for: Inland Waterways Authority of India (Ministry of Shipping, Govt. of India) A-13, Sector – 1, NOIDA Distt. GautamBudh Nagar, Document Distribution Date Revision Distribution Hard Copy Soft Copy INLAND WATERWAYS 31 Oct 2016 Rev – 0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 07 Jan 2017 Rev – 1.0 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 31 Jan 2017 Rev – 1.1 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA INLAND WATERWAYS 26 Sep 2017 Rev – 1.2 04 04 Uttar AUTHORITY OF INDIA Pradesh – INLAND WATERWAYS 23 Nov 2017 Rev – 1.3 01 01 AUTHORITY OF INDIA 201 301 INLAND WATERWAYS 26 Nov 2018 Rev – 1.4 04 04 AUTHORITY OF INDIA IWAI, Region VI, AVM Canal Final Feasibility Report Page II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IIC Technologies Ltd. expresses its sincere gratitude to IWAI for awarding the work of carrying out detailed hydrographic surveys in the New National Waterways in NW- 13 in Region VI – AVM Canal from Poovar to Erayumanthurai. We would like to use this opportunity to pen down our profound gratitude and appreciations to Shri Pravir Pandey, IA&AS, Chairman IWAI for spending his valuable time and guidance for completing this Project. IIC Technologies Ltd, would also like to thanks, Shri Alok Ranjan, ICAS Member (Finance), Shri Shashi Bhushan Shukla, Member (Traffic), Shri S.K. Gangwar, Member (Technical) for their valuable support during the execution of project. IIC Technologies Ltd. wishes to express their gratitude to Capt. -

Thiruvananthapuram

Proceedings of the District Collector & Chairperson District Disaster Management Authority Thiruvananthapuram (Present: Dr:NavjotKhosa LAS) 5EARS THEELERATI MAHATHA (Issued u/s 26, 30, 34 of Disaster Management Act-2005) DDMA/01/2020/COVID/H7/CZ-183 Dtd:- 11.06.2021 Sub :COVID 19 SARS-CoV-2 Virus Outbreak Management Declaration of Containment Zones - Directions and Procedures- Orders issued- reg Read )GOMs)No.54/2020/H&FWD published as SRO No.243/2020 dtd 21.03.2020. 2)Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 01.05.2020. S) Order of Union Government No 40-3/2020-DM-I(A) dated 29.08.2020. 4) G.O(Rt) No. 383/2021/DMD dated 26/04/2021 6)G.O(Rt) No. 391/2021/DMD dated 30/04/2021 )Report from District War room, Trivandrum dated 10/06/2021 ) DDMA decision dated 28/05/2021 8) G.O(Rt) No.455/2021/DMD dated 03/06/2021 9) G.O(Rt) No.459/2021/DMD dated 07/06/2021 WHEREAS, Covid-19, is declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organisation. The Government of India also declared it as a disaster and announced several measures to mitigate the epidemic. Government of Kerala, has deployed several stringent measures to control the spread of the epidemic. Since strict surveillance is one of the most potent tool to prevent the occurrence of a community spread, the government has directed district administration to take all possible measures to prevent the epidemic. AND SRO WHEREAS, notification issued by Govt of Kerala as Kerala Epidemics Diseases, Covid 19, Regulations 2020 in official gazette stipulates that all possible measures shall be incorporated to contain the disease. -

Shoreline Change Analysis of Vizhinjam Coast Using Satellite Images

Restricted Distribution SHORELINE CHANGE ANALYSIS OF VIZHINJAM COAST USING SATELLITE IMAGES ANNUAL REPORT (October 2017 to September 2018) FOR ADANI VIZHINJAM PORT PVT LIMITED PREPARED BY Coastal and Environmental Engineering Division NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OCEAN TECHNOLOGY CHENNAI OCTOBER, 2018 Comprehensive Shoreline Monitoring Programme NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF OCEAN TECHNOLOGY (Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India) NIOT Campus, Velachery-Tambaram Road, Pallikkaranai, Chennai-600 100 Tel: +91 044 66783440, Fax: +91 044 22460275 Email: [email protected] Web: www.niot.res.in Report Summary Client Client’s representative Adani Vizhinjam Port Pvt Limited. Mr. Manoranjan Tripathy, DGM-Projects Vizhinjam International Seaport Dr. Jayakumar, Managing Director and CEO Limited. Project Project No. NIOT/CEE/1301 Shoreline change analysis study MoA NIOT-VISL-AVPPL dated 03.08.2017 using high resolution satellite SO No. 5700227001 dated 15/11/2017 images 1 Draft Report SSP/DSK BKJ MVR 31-October-2018 2 Final Report SSP/DSK BKJ MVR 03-January-2019 3 Revised Report- I SSP/DSK BKJ MVR 05-March-2019 4 Revised Report- II SSP/DSK BKJ MVR 09-April-2019 Revision Description By Checked Approved Date Key words Classification Open Internal Proprietary Distribution No of copies AVPPL/VISL 2 NIOT, Chennai. 1 ii Comprehensive Shoreline Monitoring Programme CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Previous Studies on sediment transport .................................................................. -

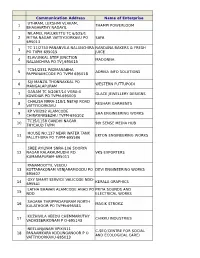

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

Annual Report 2003-04 1

SOUTH INDIAN FEDERATION OF FISHERMEN SOCIETIES Annual Report 2003-04 1 Annual Report 2003 -04 SOUTH INDIAN FEDERATION OF FISHERMEN SOCIETIES ANNUAL REPORT 2003 - 2004 Karamana, Thiruvananthapuram Kerala, India 2 Annual Report 2003-04 Published by South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies Karamana (P.O) Thiruvananthapuram - 695 002 Kerala, India Tel: (91) 471- 234 3711, 234 3178 Fax : (91) 471 - 234 2053 Email : [email protected] Website : http://www.siffs.org Designed by C.R.Aravindan Photograph by S.Sajith Printed at G.K. Printers, Ernakulam Annual Report 2003-04 3 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 Technological Services .............................................................................................. 2 Post Harvesting and Marketing.............................................................................. 10 Information Services ................................................................................................. 13 Membership/Cooperative Services ........................................................................ 22 Expansion of Society Network ............................................................................... 22 Stregthening of Member Federations .................................................................... 24 Financial Services ....................................................................................................... 26 Other Services ...........................................................................................................