Water Security in the Middle East Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate

SNHR is an independent, non-governmental, nonprofit, human rights organization that was founded in June 2011. SNHR is a Thursday 31 October 2013 certified source for the United Nation in all of its statistics. The Documentation of the Sectarian Massacre of Talkalakh City in Homs Governorate The documenting party: Syrian Network for Human Rights On Thursday 31 October 2013, about 11:00 pm, a group of “local committees” entered the house of an IDPs family in Al Zara village in Talkalakh city and slaugh- tered a woman and her two children with knives. The location on the map: Alaa Mameesh, the eldest son of the family, told SNHR about the slaughtering of his mother and two brothers at the hands of pro-regime forces Al Shabiha: “The family displaced from Al Zara village due to clashes between Free Army and the regime army which consists of 95% Alawites in that area. The family displaced to Talkalakh city which is controlled by the regime hoping the situation would be better there. When Al Shabiha knew that the building contains people from Al Zara village, they stormed the house and without any investigation they killed them all, my mother, my sister and my brother. My father, Fat-hi Mameesh is an officer in the regime army, he fought the Free Army in many battels. Al Shabiha haven’t asked my family about any information. They killed them only because they are IDPs from Al Zara village which is of a Sunni majority. We couldn’t identify anything about their corpses or whether they buried them or not because they banned anyone from Al Zara village to enter Talkalakh city” 1 www.sn4hr.org - [email protected] The victims’ names: The mother, Elham Jardi/ Homs/ Al Zara village/ (Um Alaa) Hanadi Fat-hi Mameesh, 19-year-old/ Homs/ Al Zara village Mohammad Fat-hi Mameesh, 17-year-old/ Al Zara village. -

Capoeta Aydinensis, a New Species of Scraper from Southwestern Anatolia, Turkey (Teleostei: Cyprinidae)

Turkish Journal of Zoology Turk J Zool (2017) 41: 436-442 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/zoology/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-1510-43 Capoeta aydinensis, a new species of scraper from southwestern Anatolia, Turkey (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) 1 2 1, 2 1 Davut TURAN , Fahrettin KÜÇÜK , Cüneyt KAYA *, Salim Serkan GÜÇLÜ , Yusuf BEKTAŞ 1 Faculty of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Rize, Turkey 2 Faculty of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Süleyman Demirel University, Isparta, Turkey Received: 16.10.2015 Accepted/Published Online: 27.10.2016 Final Version: 23.05.2017 Abstract: Capoeta aydinensis sp. nov. is described from the Büyük Menderes River and the streams Tersakan, Dalaman, and Namnam in southwestern Turkey. It is distinguished from all other Anatolian Capoeta species by the following combination of characters: one pair of barbels; a plain brownish body coloration; a well-developed keel in front of the dorsal-fin origin; a slightly arched mouth; a slightly convex lower jaw with a well-developed keratinized edge; a weakly ossified last simple dorsal-fin ray, serrated along about 60%–70% of its length, with 14–20 serrae along its posterior edge; 58–71 total lateral line scales; 11–12 scale rows between lateral line and dorsal-fin origin; 7–9 scale rows between lateral line and anal-fin origin. Key words: Büyük Menderes, Capoeta, new species, Turkey 1. Introduction 2. Materials and methods Anatolian species of the genus Capoeta have been Fish were caught using pulsed DC electrofishing intensively studied in the last decade (Turan et al., 2006a, equipment. The material is deposited in the Recep Tayyip 2006b, 2008; Özuluğ and Freyhof, 2008; Schöter et al., 2009; Erdoğan University Zoology Museum of the Faculty of Küçük et al., 2009). -

Civilians in Hama

Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama Two young men were kidnapped by the National Defense Militia; the other 11, belonging to the same family, were abducted by a security service in Hama city. The abductees were all released in return for a ransom Page | 2 Syria: 13 Civilians Kidnapped by Security Services and Affiliate Militias in Hama www.stj-sy.org In November 2018 and February 2019, 13 civilians belonging to two different families were kidnapped by security services and the militias backing them in Hama province. The kidnapped persons were all released after a separate ransom was paid by each of the families. Following their release, a number of the survivors, 11 to be exact, chose to leave Hama to settle in Idlib province. The field researchers of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ contacted several of the abduction survivors’ relatives, who reported that some of the abductees were subjected to severe torture and deprived of medications, which caused one of them an acute health deterioration. 1. The Kidnapping of Brothers Jihad and Abduljabar al- Saleh: The two young men, Jihad, 28-year-old, and Abduljabar, 25-year-old, are from the village of al-Tharwat, eastern rural Hama, from which they were displaced after the Syrian regular forces took over the area late in 2017, to settle in an IDP camp in Sarmada city. The brothers, then, decided to undergo legalization of status/sign a reconciliation agreement with the Syrian government to obtain passports and move in Saudi Arabia, where their family is based. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013

United Nations S/2012/401 Security Council Distr.: General 8 January 2013 Original: English Identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, and 1 and 4 June 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 3 June 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 13-20354 (E) 170113 210113 *1320354* S/2012/401 Annex to the identical letters dated 4 June 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Sunday, 3 June 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. On 2/6/2012, from 1600 hours until 2000 hours, an armed terrorist group exchanged fire with law enforcement forces after the group attacked the forces between the orchards of Duma and Hirista. 2. On 2/6/2012 at 2315 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device in a civilian vehicle near the primary school on Jawlan Street, Fadl quarter, Judaydat Artuz, wounding the car’s driver and damaging the car. -

Cooperation on Turkey's Transboundary Waters

Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Status Report commissioned by the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety F+E Project No. 903 19 226 Oktober 2005 Imprint Authors: Aysegül Kibaroglu Axel Klaphake Annika Kramer Waltina Scheumann Alexander Carius Project management: Adelphi Research gGmbH Caspar-Theyß-Straße 14a D – 14193 Berlin Phone: +49-30-8900068-0 Fax: +49-30-8900068-10 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.adelphi-research.de Publisher: The German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety D – 11055 Berlin Phone: +49-01888-305-0 Fax: +49-01888-305 20 44 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.bmu.de © Adelphi Research gGmbH and the German Federal Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, 2005 Cooperation on Turkey's transboundary waters i Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 1.1 Motive and main objectives ........................................................................................1 1.2 Structure of this report................................................................................................3 2 STRATEGIC ROLE OF WATER RESOURCES FOR THE TURKISH ECONOMY..........5 2.1 Climate and water resources......................................................................................5 2.2 Infrastructure development.........................................................................................7 -

Hydropolitics and Issue-Linkage Along the Orontes River Basin:… 105 Realised in the Context of the Political Rapprochement in the 2000S, Has Also Ended (Daoudy 2013)

Int Environ Agreements (2020) 20:103–121 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09462-7 ORIGINAL PAPER Hydropolitics and issue‑linkage along the Orontes River Basin: an analysis of the Lebanon–Syria and Syria–Turkey hydropolitical relations Ahmet Conker1 · Hussam Hussein2,3 Published online: 13 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The Orontes River Basin is among the least researched transboundary water basins in the Middle East. The few studies on the Orontes have two main theoretical and empirical shortcomings. First, there is a lack of critical hydropolitics studies on this river. Second, those studies focus on either the Turkish–Syrian or Lebanese–Syria relations rather than analysing the case in a holistic way. Gathering both primary (international agreements, government documents, political statements and media outlets) and secondary sources, this paper seeks to answer how could Syria, as the basin hydro-hegemon, impose its control on the basin? This study argues that the lack of trilateral initiatives, which is also refected in academic studies, is primarily due to asymmetrical power dynamics. Accordingly, Syria played a dual-game by excluding each riparian, Turkey and Lebanon, and it dealt with the issue at the bilateral interaction. Syria has used its political infuence to maintain water control vis-à-vis Lebanon, while it has used non-cooperation with Turkey to exclude Tur- key from decision-making processes. The paper also argues that the historical background and the political context have strongly informed Syria’s water policy. Finally, given the recent regional political developments, the paper fnds that Syria’s power grip on the Orontes Basin slowly fades away because of the changes in the broader political context. -

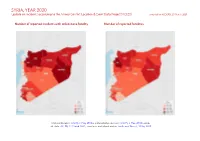

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

To Read the Full Report As a PDF, Follow This Link

Arbitrary Deprivation of Truth and Life An accurate, transparent, and non-discriminatory approach must be adopted by the Syrian State when issuing “death statements” 1 2 Executive Summary Hostilities forced Samar al-Hasan, 40, and her family to flee their home in Ma'arrat al-Nu'man city and settle in a makeshift camp in Harem city, within rural Idlib province. Before the family fled, Samar’s husband was killed in a regime rocket attack on their neighborhood. Now, Samar lives with her children in her family’s tent, unable to afford taking care of her children or herself without help. One source of her financial troubles is the Syrian government’s refusal to give Samar her husband’s death statement, a document which would allow her and her children to access her husband’s will. The wrinkles on Samar’s forehead speak of her suffering since her husband’s death in 2018. Even as she wistfully recalls for Syrians for Truth and Justice the comfortable years she spent in Ma'arrat al-Nu'man with her husband, she knows they will never return. A “death statement” formally documents the death of a person. Obtaining a death statement allows a widow to remarry – if she wishes – after the passage of her “Iddah”.1 A death statement is also required to initiate a ‘determination of heirship’ procedure by the deceased's heirs (incl. the wife, children, parents, and siblings). In Syria, “death statements” are distinct from “death certificates”. A death certificate is the document that confirms the occurrence of death, issued by the responsible local authorities or the institution in which the death took place, such as hospitals and prisons, or by the “Mukhtar” – the village or district chief, who keeps a local civil registry. -

New Data on the Distribution and Conservation Status of the Two Endemic Scrapers in the Turkish Mediterranean Sea Drainages (Teleostei: Cyprinidae)

International Journal of Zoology and Animal Biology ISSN: 2639-216X New Data on the Distribution and Conservation Status of the Two Endemic Scrapers in the Turkish Mediterranean Sea Drainages (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) Kaya C1*, Kucuk F2 and Turan D1 Research Article 1 Recep Tayyip Erdogan University, Turkey Volume 2 Issue 6 2Isparta University of Applied Sciences, Turkey Received Date: October 31, 2019 Published Date: November 13, 2019 *Corresponding author: Cuneyt Kaya, Faculty of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, DOI: 10.23880/izab-16000185 Recep Tayyip Erdogan University, 53100 Rize, Turkey, Tel: +904642233385; Email: [email protected] Abstract In the scope of this study, exact distribution of the two endemic Capoeta species in the Turkish Mediterranean Sea drainages was presented. Fishes were caught with pulsed DC electro-fishing equipment from 28 sampling sites throughout Turkish Mediterranean Sea drainages between Göksu River and stream Boğa. The findings of the study demonstrate that Capoeta antalyensis inhabits in Köprüçay and Aksu rivers, and streams Boğa and Gündoğdu, all around Antalya. Capoeta caelestis widely distributed in coastal stream and rivers between Stream Dim (Alanya) in the west and Göksu River (Silifke) in the east. Metric and meristic characters were collected from the fish samples which obtained in the field for Capoeta caelestis and Capoeta antalyensis, and museum material for Capoeta damascina. In this way, morphologic features of the species revealed and Capoeta caelestis compared with Capoeta damascina to remove the hesitations about the validity of the species. The conservation status of Capoeta antalyensis was recommended to uplist from Vulnerable to Endangered. Keywords: Freshwater Fish Species; Anatolia; Pisces; Capoeta antalyensis; C. -

Flash Update | Monitoring Violence Against Healthcare Health Sector

Flash Update | Monitoring violence against healthcare Health Sector | Syria Hub Flash Update # 36 Date: 06/06/2019 Time of the incident: between 6.15 to 7.30 p.m. Location North-West Hama, Mahardah City HF Name & Type Al-Mahabah private hospital Attack type Violence with heavy weapons Incident On Thursday 6 June between 6.15 to 7.30 p.m., Al-Mahabah private hospital in North West Hama was reportedly targeted by Indirect rockets three times. Prior Health Facility The hospital was fully functioning, partially damaged, provided: 120 condition out-consultations (x-ray), 350-400 surgical operations (including CSs), 75-80 normal deliveries, 30 babies in incubator, 50 hospitalized patients during May 2019 Impact . The hospital was reportedly partially damaged, as follow: - Main façade, most glasses of the hospital were destroyed. - Some rooms (emergency room, general surgery, one patient room) have become out of service. - 10 air conditioners were destroyed. Victims of the Attack Total Deaths: (0) Health Care Providers: 0 Auxiliary Health Staff: 0 Patients: 0 Others: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Males: 0 Females: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Age < 15 years: 0 Age ≥ 15 years: 0 Total Injuries: (0) Health Care Providers: 0 Auxiliary Health Staff: 0 Patients: 0 Others: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Males: 0 Females: 0 -------------------------------------------------------- Age < 15 years: 0 Age ≥ 15 years: 0 Disclaimer: The information presented in this document do not imply the opinion of the World Health Organization. Information were gathered through adopted tools (i.e., HeRAMS) & other sources of information, and all possible means have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this document. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied.